It’s 7 o’clock in the morning and the sun is just rising over the horizon. It’s cold and windy. A small boat has made its way to shore with 48 people on board. They get out and stumble directly onto the beach, wet and exhausted but smiling with relief. There are three older Greek ladies sitting on a small bench observing them, passive and indifferent. They get up and go back home. They come back the next day like they have been doing for over a year.

Until 29 November 2015, the main landing site for refugees and immigrants was the northern side of the Greek island Lesvos; between the towns of Skala Sikamineas and Molyvos. The journey is relatively short, only around two hours. However the situation has changed after an agreement between the European Union and Ankara. Turkey, in exchange for 3 billion euros, has downscaled the influx of refugees and immigrants to Europe. Now only small dinghies are able to reach Skala Sikamineas. Whereas before the agreement, up to 30 would land daily on the local, picturesque beach.

At the beginning of the crisis, not all migrants had life jackets because they were an added expense. Smugglers in Turkey concluded that since not everyone could afford real ones, why not provide travellers with cheap fakes?

Now immigrants have to sail from the Turkish city of Ayvalik, where there are less law enforcement officials. In order to not be discovered by the Turks, refugees and immigrants are having to hide in the woods for several days. This newly Greek town is further away from Turkey, resulting in the perilous journey taking up to 4 hours. With the situation being so unstable, no one knows where the dinghies will be forced to sail next.

“Allah Akbar”!

From the town of Ayvalik, small boats arrive into Mytilene, the largest city on the Greek island of Lesvos. Volunteers hand out thermal blankets and offer first aid where necessary. The temperature is around 10 degrees, however the damp makes it seem colder.

Increasingly, refugees and immigrants are forced to travel at night now that the Turks have increased controls at the border. A dinghy from Ayvalik, arrives at midnight on the coast of Lesvos and those on board are unsure of their location.

“City?” An Afghan asks.

“Mytilene,” I answered.

“Country?”

“Greece.”

He leaves smiling. Meanwhile, his friends are kneeling, kissing the ground and whispering “Allah Akbar”.

Yamaxa instead of Yamaha

After fifteen minutes of a dinghy arriving on the Greek shores, the only items remaining on the beach are orange life jackets. The boats have been deflated and removed by Greek law enforcement officials.

Ninety percent of the life jackets are Chinese fakes, offering no buoyancy if the boat was to capsize. At the beginning of the crisis, not all migrants had life jackets because they were an added expense. Smugglers in Turkey concluded that since not everyone could afford real ones, why not provide travellers with cheap fakes? This became the norm and now, every single migrant wears a life jacket that does not provide any protection whatsoever.

Over 400 thousand people have arrived on Lesvos since the beginning of 2015. Between the towns of Skala Sikamineas and Molyvos their mark is left by a huge pile of discarded lifejackets.

“If we don’t do something with this ever growing mountain of lifejackets in the upcoming months, the island will be facing an ecological catastrophe,” admits the special advisor to the Lesvos mayor, Marios Andriatis. “But I would like to calm everyone down, because we have ideas on how to deal with this problem,” he adds.

It was only when the situation started to became more severe that the authorities began to look into possible solutions. However they were still unsure of which of the three selected options would be chosen.

“The first one suggests using the plastic elements of the life vests to build tents for migrants,” says the advisor, Andriatis. “We could also remake the vests into backpacks for migrants or recycle the waste”.

What exactly will happen with the 70 tonnes of waste left by migrants won’t be known for 3 or 4 months. City authorities will then have to choose one of the solutions and implement it. Another question is what to do with the boats and engines? This year alone, over 7,000 boats have arrived on Lesvos. Smugglers put the migrants onto the flimsiest of dinghies powered by cheap, substandard engines and not surprisingly, dramatic scenes on the open seas are common.

It’s 2 am. Cars with volunteers inside are waiting on the shore. They park on the beach and turn on their lights to guide the boats to safety. In one car, four volunteers are observing a rescue operation unfold. The Greek coastguard has pointed his beams towards a small wooden dinghy. Over 25 people including children are on board. The engine had broken down and the Greeks were towing them to shore. Fortunately this time the rescue attempt was successful but others haven’t been so lucky. Last year 2,500 migrants died or went missing, trying to reach Europe by sea (UNHCR data from the end of August 2015).

Take my word for it

Immediately after the boats reach the coast, UNHRC buses arrive to take the refugees to the Moria camp where they are registered.

“The Greeks have no money. They are very good to us, but here there is no work at all, there is a crisis. What could we possibly do in Greece?”

There have been about 10,000 people in the Moria refugee camp during the height of the crisis. Now there are five times fewer according to the Greek policemen who guard the camp. This number changes daily, depending on whether the wind is blowing on the sea, or it is calm. For the local people of Lesvos, wind means peace.

The camp in Moria consists of several containers surrounded by barbed wire. Some refuse to live in such conditions, so they put up tents in the hills close to the camp. Mostly Afghans settle there using open fires for heat. Migrants from Syria, Palestine, Yemen, Somalia, Sudan, Eritrea and Morocco register in the furthest part of the camp. Afghans, Iranians, Iraqis, Lebanese and Pakistanis in the closer one.

Migrants wait in line to register. When they finally manage to enter the camp they must provide their personal details. This includes scanning their fingerprints. Most of the people who come here do not have documents. Their testimony is therefore accepted on a “take my word for it” basis. However, there are on-site workers who verify their skin colour and dialect as well as checking whether migrants are telling the truth during this first phase of registration. The Greek authorities issue papers, allowing the migrants to continue their journey. They are eager for them to leave Greek soils.

“How could we live here?” asks Szihad, a 28-year old Iranian, who was working in a cafe back in Tehran. “The Greeks have no money. They are very good to us, but here there is no work at all, there is a crisis. What could we possibly do in Greece?”

Yalla, yalla!

For Syrians, another camp was created in Kara Tepe, closer to Mytilene. Kara Tepe consists of 160 IKEA-style huts and 20 tents. Although the camp has only officially existed for three months, it has been functioning since April. When I was in Kara Tepe, the wind was blowing at sea, so there were only 80 people spending the night inside the camp. But the day before there were 800 migrants. The Mayor declares that Kara Tepe can host up to 2,000 people.

“Welcome to our village,” says Moragiannis Stavros, a tall, well-built Greek in his forties, who is head of the camp. “I’m talking about a village, not a camp, because we have our own community here. We want to create a family atmosphere… We are hosting guests here.”

The migrants are not demanding. All they ask for are food, blankets and a place to sleep. Currently in Kara Tepe preparations for winter are underway. The roofs are being covered, houses are being furnished with wooden floors and heating installed. All this is to ensure humane conditions for the migrants. But nobody stays here for longer than 2-3 days.

After I left the Kara Tepe camp, I heard Moragiannis Stavros meet a French photojournalist who had come to visit the camp.

“Welcome to our village,” his voice carried through the camp.

The migrants are eager to move on, they hurry to the ferry travelling to Athens. Fathers shout to their children and wives, “Yalla, yalla” (hurry, hurry) and get into one of the dozens of the taxis waiting at the camps. In the Moria camp alone, there were fourteen of them that day.

A taxi to the port from Moria costs 10 euros. Considering that the locals are selling Snickers bars for around 2 euros at food stalls around the camp, it is surprisingly cheap for the migrants. All modes of transport – as a general rule – are the same price for Greeks, tourists and migrants. A ticket from Lesvos to Athens costs 48.5 euros.

When immigrants arrive at the port, Greek police organize them into queues. The officers are eager to help but are also overcome with anxiety.

When the border guards towed a wooden dinghy with a broken down engine to the port, police officers could not agree to whether or not to let volunteers help the frozen migrants to the police station.

“No one can enter these premises!” said one stocky senior official.

“There are women and children here, they need blankets,” said the other officer. After a brief exchange of opinions, the more compassionate of the two won this time.

There is no conflict between migrants and residents, states the mayor of Lesvos. The local community understand what most of these people have been through. This can be seen through no incidents yet being reported.

The mayor’s office is now well-practiced at responding to reporters’ questions about possible conflicts between the Greeks and migrants. It had problems in the beginning in dealing with the press but has now mastered press relations and the correct narrative. I am the 145th journalist who has talked with the authorities of Lesvos.

“If you live in Greece, you are not interested in the topic of refugees, it has become a part of our everyday reality.”

Everyday reality

The ferry journey from Lesvos to Athens takes approximately 12 hours. Ships depart usually around 8pm and they reach Athens in the morning. The ferry is the first place that offers the migrants a moment of real rest. In the camps – despite the fact that the UNHCR, the Red Cross and dozens of volunteers do their best – you can still feel the tense atmosphere. The ferry journey is the first opportunity that the migrants have to catch a breath and reflect on the arduous trip that they have so far undertaken.

On-board, most people sleep. But from time to time you hear a voice on the loudspeaker giving a warning in Greek, English and Arabic, to mind your belongings. The thieves prowling the ferries rob everyone equally, migrants as well as Greeks.

From the port of Piraeus, refugees and immigrants take buses, tickets for which most people buy while still on Lesvos. A further journey to the Greek/Macedonian border costs another 40 euros.

Those who do not have the money for tickets go to the Eleonos camp. It is located in the industrial district of Athens surrounded by abandoned factories. Here they can sleep and eat something warm. The camp is well stocked, but despite the continual arrivals of migrants to Europe, it has not been full for a long time. Some prefer to camp out on Victoria Square in the center of Athens. They sit on benches or sleep on cardboard boxes among the Greeks who have become accustomed to their presence.

“If you live in Greece, you are not interested in the topic of refugees, it has become a part of our everyday reality,” says Iakovos, a 25-year-old graduate of political science.

The border

Idomeni, a small village on the Greek-Macedonian border, 547 kilometers away from Athens, has fewer than 300 inhabitants.

Buses are supposed to be taking migrants to Evzoni, the official border crossing. But in reality, refugees go to the area of Idomeni, located a few kilometers from the official border crossing. There, by the railroad tracks, hundreds of thousands of people have been crossing the border for the past 18 months.

Since 17 November, approximately 2 to 3 thousand people have been living in Idomeni. They are migrants who have not come from Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria as from mid-November only citizens of these three countries have been allowed into Macedonia. This was decided by the Balkan countries (Croatia, Macedonia, Serbia and Slovenia) who are likely to have quietly consulted their decision with Berlin.

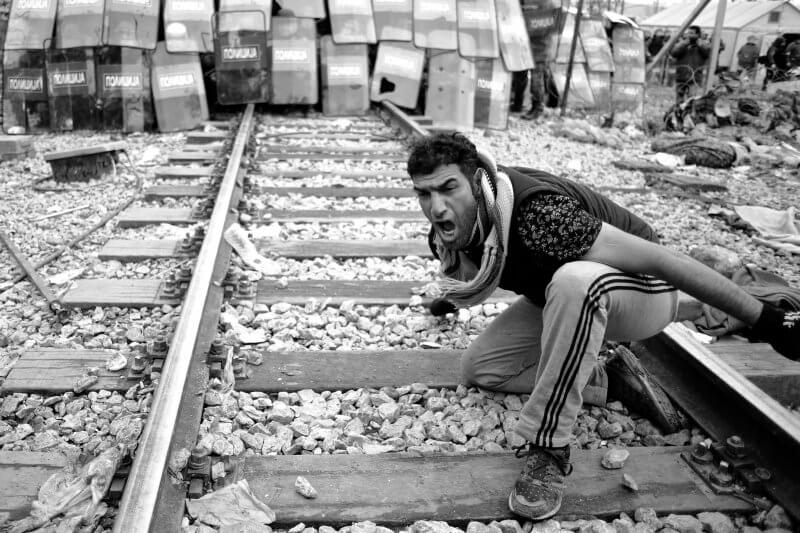

Occasionally, clashes took place in Idomeni between Algerians, Iranians, Moroccans, Pakistanis and law enforcement officials. The first time this occurred was in late November, when a Moroccan national wanted to commit suicide by throwing himself onto railway tracks. A crowd began to gather around the medical tent, only to move to the front of the Macedonian police cordon. Here the first stones were thrown.

The riot lasted 1.5 hours. Despite the migrants calming down, the situation repeated itself a few days later. Except this time the first fatality was witnessed after a migrant was struck by a rock.

Local authorities have expressed dissatisfaction with the presence of thousands of people on the border. They have been dealing with the migrant crisis much longer than other countries. Now, with even more people arriving onto the Greek shores, the local government is experiencing even greater problems.

“Migrants are destroying the fields,” says Ioannis Adamopoulos, vice-mayor of Polykastro, in charge of the Idomeni village. “But people are also simply afraid, because the refugees sometimes knock on their door in the middle of the night. Or sleep hidden in the warehouses.”

I spoke with Adamopoulos in the city hall of Polykastro as the Mayor had gone to Thessaloniki for an urgent meeting. There was a lot of activity going on in the hall as a result of the extra work that they have been experiencing in the last two years due to the migrant crisis. In the room with us was also Xanthipi Soupli, the leader of the local community in Idomeni.

“In Idomeni practically everyone makes their living by working in the fields,” says Soupli.

“When refugees and migrants cross the fields, they destroy them. Now, while we’re dealing with the migrant crisis, Greeks have nothing to make a living out of,” says a woman, about forty years old, whilst smoking a cigarette. “People are welcoming towards refugees and immigrants, it’s not their fault that they sleep in the fields, but the problem still exists”.

“We Greeks are famous for our hospitality,” says Alexis, a 31-year-old PR officer from Polykastro, “we have proved it in so many different ways already.”

On 9 December, Greek police carried out an order to “clear” the border. Migrants were transported by bus to Athens and Thessaloniki where they are waiting to see what happens.

Germany, Germany

The scenario in Idomeni looks similar to every other transit point on route. Migrants quickly come out of the buses, walk a few hundred meters, show documents obtained in Lesvos and travel on (if they are from Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria). Throughout the journey you can hear the children crying and fathers calling – “Yalla, Yalla”.

In Idomeni, when I asked Muhammad, a 21-year-old Pakistani who studies sociology where he was going, he replied: “Germany, Germany.”

Just like his compatriot Mustafa, a 36-year-old English teacher, Mustafa also knows exactly why he is going to Europe.

“Europeans respect knowledge and science more than us. In Europe, more respect is given to human relations.” After a while he adds: “Well … and the standard of living is better.”

This article was written in December 2015. Since then some facts may have changed. The material was created thanks to partial funding from the Media Fund.

Translation by Marta Wieloch.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)