A few retired police officers sat down with Dawid Krawczyk of Political Critique for a discussion on the war on drugs.

Leszek Wieczorek started his career in the 80s and worked as a criminal investigator in Bielsko-Biała, Poland. He chased down users of “kompot” (a.k.a. Polish heroin). Later in the 90s when amphetamine became popular, he was in charge of international investigations conducted in Poland and Germany.

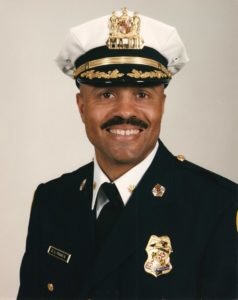

Neill Franklin is from Baltimore, Maryland. He started working undercover at the very beginning of his career. “They [narcotics squad] were driving fancy cars. They wore whatever costume they wanted, whatever clothes they wanted. I wanted to become one of them,” he recalls.

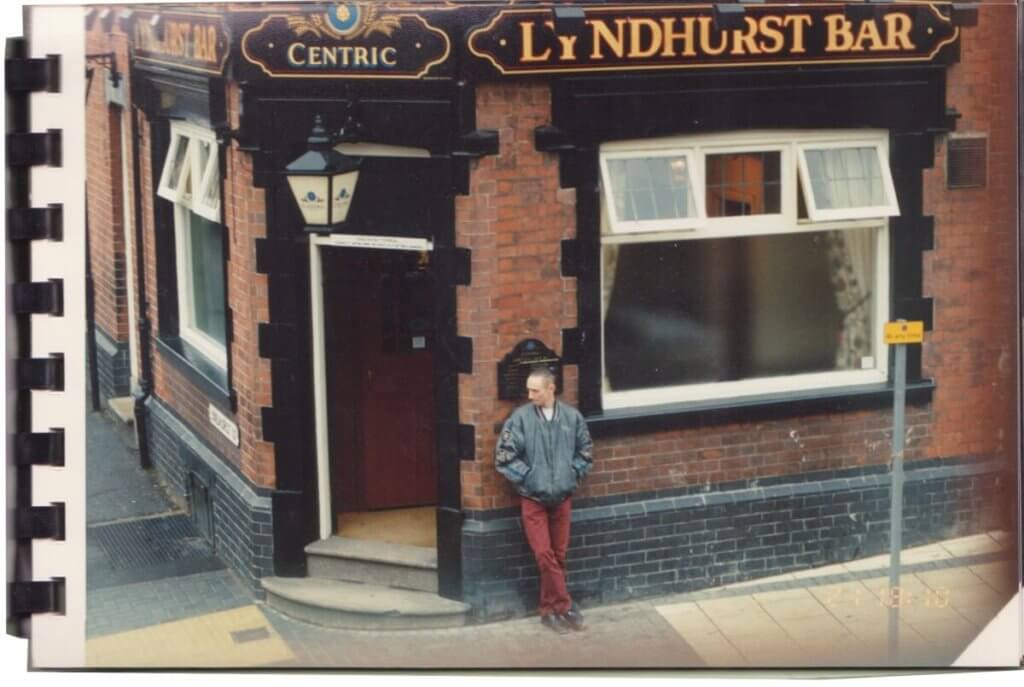

Neil Woods served in Derbyshire, England, but travelled all over the United Kingdom conducting operations that usually lasted a few months. His objective was to befriend the most dangerous criminals in Britain, collect evidence, and then arrest them.

All three are members of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP), a pro-legalisation advocacy group formed exclusively of ex-law enforcement officials who oppose drug prohibition. Neill Franklin, still living in Baltimore, is the Executive Director of LEAP. And Neil Woods wrote a book titled, Good Cop, Bad War, in which he revealed details on covert operations in which he took part as an undercover cop. Neil believes that police tactics are partially to blame for the existence of ruthless and brutal drug lords. Leszek Wieczorek retired in 1999, and in 2010 joined LEAP as the first member from Poland. He has given speeches at pot legalisation rallies and advocates for drug policy reform in Poland.

All had their own reasons for leaving the force, as they all changed their positions on drugs at different stages of their careers. In the interview with Dawid Krawczyk, they tell a story starting at the forefront of the war on drugs, ending with an anti-prohibitionist stance. How did they move from believing Nancy Reagan’s rhetoric to demanding a reform in drug policy?

Dawid Krawczyk: Why would you even go into police work?

Neill Franklin: For me, it was about public service, about making things better.

Leszek Wieczorek: It was a job, like any other job.

Neil Woods: I went to the police force by flipping a coin. It was literally flippant. It was that or a backpacking tour.

All of you worked in drug squads. Did you plan to do that from the beginning?

Neill Franklin: When I went into police work it had absolutely nothing to do with drugs. My brother had become a Maryland state trooper a few years before I went into it. He was older than me and I got to see what it was like for him and decided to give it a try. It was just on a whim.

When I graduated from the police academy I worked on patrol probably for no longer than 18 months, and then I started working undercover in drugs.

Did you want to catch drug lords and make Baltimore streets free of drugs?

Neill Franklin: The actual reason I went into undercover work was because I thought it was cool. There was this group of shady characters in my barracks in the basement. They would come and go at all hours of the day and night. They drove fancy cars, wore whatever costume they wanted, whatever clothes they wanted. “Who are these guys?” I thought. Then I found out they were a narcotics squad. And one of them said to me: “Hey, man, we’d like to have you on the team.” And next thing you know, I was one of the shady ones. In and out of the basement. It was cool.

Leszek Wieczorek: My motivations weren’t particularly lofty as well. My friend had told me the police were recruiting. I was young and looking for an adventure. So, my career took off. It didn’t take me much time to be promoted to prestigious positions. I knew after some time it was the path I should follow. I won’t beat around the bush, I was perceived to be a good cop.

When were you working as a police officer, exactly?

In the 80s, during the old regime. I worked with the criminal police in Bielsko-Biała, doing criminal cases most of the time, but drugs were still something new. What we were basically doing was chasing down guys with “kompot” [polish heroine] on them. Amphetamines weren’t a thing yet. But in the 90s, right after the transition from communism to capitalism, we were opened up to the world, and travels to Germany started. If you organised a party back then, there was a good chance that the highlight of the evening would be amphetamine.

Neil, after you flipped the coin, did you decide to continue with police work because of cool clothes and fancy cars?

Neil Woods: Once I was in the police force I wanted to fight the good fight and catch the bad guys. Very much in line with my favourite fiction. It was quite naive as well. I was influenced by the narrative that drugs destroy communities. I clearly remember Nancy Reagan on TV saying: “One smoke of crack cocaine and you’re addicted for live.” I totally bought this “Just Say No to Drugs” narrative. At that time I fell for the idea that drugs are causing problems, because it is addictive and if you try it, you’re stupid, and if you can’t get off it, you’re just lacking willpower.

I was catching nasty people, to be fair the dealers were the nastiest people, they were doing the most violence. So, when I had the chance to get into undercover work, I didn’t hesitate a bit. In the UK that type of work was very new, though it’s obviously been going on in the U.S. for a long time. It’s fair to say that we were pioneers of it.

And to answer your question, no, I didn’t have nice clothes and fancy cars. Usually, I was wearing some torn jacket and charity shop jumper. Most of the time my task was to score some heroin or crack from a local gangster. A few months on the job was spent befriending and gaining the trust of some of the most dangerous criminals in Britain, to get evidence and lock them up.

When Nancy Reagan started her campaign against drugs, you – Neill – had already spent a few years working in a narcotics squad.

Neill Franklin: Oh, I remember her speech. I was out of narcotics work and I was starting going up the ranks and then supervising task forces who were still doing the same work. And I’ll be honest with you. It didn’t really ring so much with me. I was already deep into it. I would believe that the “Just Say No” campaign had its place, but it can’t stand alone. But even then I knew that it’s difficult to say no to drugs.

As a young black male growing up in some of these poor rough communities in Baltimore, you have to leave your home in the morning and walk to school, walking by groups of young men selling drugs on corners. They are “crew members” and they protect each other. You’re by yourself and vulnerable in a number of different ways. Number one: it’s a dangerous neighbourhood and you have to find a way to get to and from school without being beaten up. You become a part of one of the crews so that now you’ve got protection.

You’re gonna be asked or encouraged or coerced to stand on one of the corners, and it might begin with just holding a package. It usually begins with being a lookout, letting the other boys know when the police are coming.

You might have the worst tennis shoes you have ever seen. Kids make fun of you, because of your clothes. And that lieutenant pulls out some money and tells you to go buy yourself new tennis shoes at Foot Locker and keep the change. And now, a week later he sees you again and he says: shoes look pretty good, but you know, you kinda owe me for that. Now he’s got you. So, how are you supposed to say no to drugs?

If you don’t even have tennis shoes, it’s probably not so easy to say no to police, when they are asking for a favour. Is it, Leszek?

It’s true that we have primarily focused on poor communities and people who have been trampled by the tactics of undercover work have generally been vulnerable and poor.

Leszek Wieczorek: It’s not a secret that the police are using informants in their everyday work. It’s part of the police arsenal. You can stop a young fragile guy with a splif on him, and he’ll tell you everything he knows about the shady business done by his friends or neighbours.

The value of this intel differs pretty widely. Many people from lower classes provided information that was practically worthless. They would make up some story, or just tell an outright lie. I can’t even imagine how much money we’ve lost on checking some bullshit.

Neil, your book Good Cop, Bad War is full of characters from the margins of society. Why were you consistently working in impoverished areas of Britain? People of all classes use drugs, don’t they?

Neil Woods: This is true. And it is also true that we have primarily focused on poor communities and people who have been trampled by the tactics of undercover work, the people I’ve manipulated in order to get to the gangsters have generally been vulnerable and poor. The tactics had a massive impact on already poor communities.

But I have done undercover work in more lucrative places too, though very rarely. There was this one operation in a cathedral district of Nottingham. We had received some intelligence about an enormous amount of cocaine being sold, linked to a particular gangster. I thought it was great, I got to wear some clean clothes. I got to go to some nice wine bars.

I was well dressed and gathering intelligence, it was quite easy. But interestingly, the job only went on for a few short weeks. Despite the intelligence, and the connections I was making and what I was finding, there was no interest in the white middle-class drug dealing trade.

Why was there no interest?

The political pressure and pressure from the media pushed a sort of trope about a black gangster in the inner cities. When newspapers covered stories about crack cocaine, it was generally when crack cocaine was dealt by black people. That’s why racism came into policing because the job in the wine bar just fizzled out; there was no political interest in it. You wouldn’t see any media pressure against white middle class drug users and dealers. Instead, there was only this one image posted again and again: black gangsters dealing crack cocaine in the inner cities.

You went after users of crack, heroine and kompot. You interrogated innocent pot users. And what? Suddenly, you got enlightened and stopped?

Neill Franklin: It didn’t happen suddenly, but finally we did stop. Throughout my career with the Maryland State Police, I’d get a little glimpse of something here and there. Such as in Baltimore City, when Mayor Schmoke instituted a needle-exchange program. I was like, huh, interesting health approach.

But it wasn’t a turning point. You continued working in drug enforcement for quite some time after that, right?

It wasn’t until my friend Ed Toatley was killed working undercover in Washington D.C., buying cocaine as a task force. That was in 2000. Shortly after that, we had two police officers working the streets in Baltimore city, who were killed by drug dealers. And there was the Dawson family. The family of seven in Baltimore. Five kids, the mother and father, who were killed by the neighbourhood drug dealer. One night he set the home on fire because the mother was working with the police.

I got to a point where I said this is wrong. It came to me that we have to take up the same oath as medical practitioners: Do no harm!

I can only imagine how big of an urge there was amongst police to avenge them.

When Ed was killed, there were other police officers that said: “We’re gonna go out and kick some ass. We’re gonna lock up everyone who has anything to do with these illegal drugs.” They were looking on the symptom, missing the overall issue. I felt more like “something is not right here.” Then I got to a point where I said this is wrong, I need to start speaking out about it, which I did. Once I started that journey I opened my mind to other things, then I started learning about the over-incarceration of our people, the injustice of the justice system. I just realised at some point that we need to take our foot off the gas. Stop plowing through all these people with this massive vehicle, the drug war. It came to my mind that the first thing we have to do is pretty much take up the same oath as medical practitioners: Do no harm!

Is police work in Britain generally similar?

Neil Woods: More or less the same. I had various incremental realisations as well, but there was a big event for me, where I worked an undercover job in Brighton in the UK, and the tactics were employed in such an unimaginative way that organised crime worked them out pretty quickly. They were using the most vulnerable people as proxy dealers. A lot of people were killed. Everyone on the streets, whether it was true or not, believed that it was murder, as a method of perfect control by organised crime groups.

Once I realised that it was literally protection against the tactics I was using – and had been developing for years – I could see all the harm I’d done. Over the years I have manipulated people, made lives of various individuals a lot worse, but as I’ve been going along I justified that to myself, in a sense that the end justifies the means.

The tactics are not only futile. Futile would be bad enough, but actually the policing and the tactics I was using caused massive harm to individuals and society. It leads to surrendering the control of our communities to the very worst elements in those communities.

It seems you were pumping just more violence into the system.

Absolutely, police tactics accelerate violence. It actually allows the worst violence to happen and the more intensely you police, the more intense is the violence in response. The only way out of this war is to declare peace.

Leszek, you had already retired years before you started speaking out against drug prohibition.

Leszek Wieczorek: When I was in the police force I didn’t have the slightest doubt in what we were doing. It’s like football. When you are in the game you play ball. It looks different when you are watching the game from distance. I wouldn’t have gotten involved in LEAP if it weren’t for my son. I had this enlightenment: What if my son got arrested for smoking something that is virtually harmless. He could get into some serious troubles. Come on! It’s ridiculous. He’s a righteous young man, and one joint shouldn’t decide his future.

You have to know that police work is a duty. You serve and follow orders rather than just showing up for work. So, I don’t feel remorse or anything like that, I defended law and order, and I did the best I could. Until you play on the team, you have to follow the rules and remember the goals, which are not set by regular cops, but by guys high-up in rank.

Do you still have friends who are police officers?

Leszek Wieczorek: In my case, my involvement in LEAP is not really a controversial thing. Some guys go fishing, others spend their retirement money on travelling, and I speak up against prohibition.

Neil Franklin: Let me put it this way: I didn’t lose any friends because anyone who walked away wasn’t my friend, to begin with.

Before you became so vocal against the war on drugs, you worked with the police for about 25 years. Most of your friends must have somehow been connected to the police.

The most difficult thing for many cops is to accept that they have spent two or three decades of their lives doing work that was not only non-productive but also eventually harmed their communities. If you’re going to tell me that I wasted two or three decades of my life that was detrimental to my community, I’m just not going to accept that. It’s a hard pill to swallow for folks who are die-hard cops. There are cops whose entire identity is being a police officer. They have no other life. That is their life.

I thought that undercover cops have identity problems, but of different sorts.

You mean that at the same time you’re a cop, you’re hanging out with gangsters who are living a cool life? Oh, I can totally relate to that. When they took me out of the uniform, gave me a cool car, put me into whatever clothes I wanted to wear and just told me to go work –whatever I wanted – that was just a problem waiting to happen. It is confusing, first of all: “I am supposed to be a cop and now I’m hanging out with these cats and I’m seeing, hey these guys ain’t bad. They just like to smuggle some weed, get high or whatever.” Especially when I had to go arrest some of these people, who were really good people, and at some point I had to tell them who I really am, it kind of felt wrong.

Neil, do you have a lot of readers among British policemen?

I was a whistleblower, very vocal about harms police work caused. A friend of mind had orders from the police to cease contact with me.

I had all types of police officers messaging me almost daily in support of what I wrote. Some people said they had no idea about any of it before reading the book, and thanked me for persuading them. It made me very happy that it has had such an impact on the police. But it wasn’t like that from the very beginning. When I left the police and started being active there was a massive blowback against that. People don’t want to be told that the job they’ve been doing is just not good and you don’t want to be doing that.

A friend of mine had lawful orders given out from the police: “You must no longer have contact with Neil Woods and you must delete him right now from all your social media accounts.”

You’re not only criticising the war on drugs, but also revealing police tactics.

I was a whistle-blower, definitely. I was whistleblowing tactics and being very vocal about harms police work caused.

OK, let’s say that in a few years you’re in a position to introduce new drug policy. What would be your priorities?

Neil Woods: I think there are two priorities. One absolute priority is to prescribe heroin to people who are self-medicating, who may be being sexually exploited, and those who are dependent on society.

It works in Switzerland.

There’s plenty of evidence that heroin-assisted treatment helps rescue people, and there is no excuse for governments to not have a medical solution for heroin addiction, no excuse at all. It’s urgent and achievable. The other one is that drug law reform should be primarily focused on child protection issues.

Gangsters and organized crime groups use children to transport drugs between cities and large towns; their natural response to policing is to increase such use and exploitation of children. This is particularly evident at the moment in the UK.

Why do they use children?

Well, because children are below the radar, they don’t have previous convictions, if they’re caught they don’t get a conviction. And they’re not noticed. They’re also a source of cheap labour, can be manipulated, can be easily terrified; they’re just good tools for gangsters, who want to look after their own situation. Those exploited children are the gangsters of tomorrow.

Neill Franklin: Here is the thing, you’ve got a workforce, take any business which is legal or illegal, you’ve got a workforce. How do I develop the workforce and still save money? Obviously kids don’t require as much pay as adults would, they’re not going to push back. Talking about saving money.

Let’s say you’re an adult and you’re one of my best sellers, and you got arrested. What do I have to do to get you out, to get you back on the streets? First, I’ve got to pay your bail.

How much it would be?

If you get arrested for dealing heroin in Baltimore, it would probably be 50-100 thousand dollars. I’ve got to come up with 10% of that if I use a bail bondsman. And I might not get it back. Then I’ve got to get you an attorney, to put you back on the corner.

If a kid gets arrested, number one: they get released without bail. Not only that they probably will not need an attorney, especially if it’s their first arrest. I’ve got more workforce back out on the street.

Number two, they can typically sell more, they have more energy, they’re not addicted to drugs, and they can sell in school, they’re happy to do what they’re doing. Easier to manipulate, easier to control. It’s a cost-effective move from a business standpoint. I have a better chance of instilling the fear of god in them. So at the end of the day, I’m making more money. In the regulated market you don’t have this option.

In the UK, exploitation of children is primarily connected to the teenage cannabis market; that makes cannabis regulation a priority.

Neil Woods: In the UK, the exploitation of children is primarily connected to the teenage cannabis market; that makes cannabis regulation a priority.

Leszek Wieczorek: Poland is no different from what my colleagues from the UK and the US are talking about. Who’s dealing in the clubs? Minors, of course, because it’s a perfect deal for their bosses.

Neil Woods: One last thing I wanted to add, I would suggest that there is nothing more important for the politics of global drug law reform than the growth of LEAP as an institution. We have inside knowledge from actually being on the frontlines of the war on drugs. We’re very keen in LEAP UK reaching out across Europe. Germany has their up and running LEAP, and getting great press there. There is an opportunity here for police there to connect with us, if they’re just invited.

Neill, most of your police work was done in Baltimore…

Neill Franklin: I know what’s coming. Question about The Wire, right?

You get lots of them, I understand.

All the time. But you get a free pass for asking a The Wire question. Ask whatever you need to ask.

Hamsterdam, a free drug trade area established by a visionary police officer. Did it happen in real life?

Hamsterdam was the only part of The Wire series that really wasn’t true per se. Everything else was spot on, even the characters, they were real characters. Some of the characters even got a role in the actual show; real drug dealers played roles on the show.

What they’re truly depicting with Hamsterdam is how controversial needle exchange was back in the 1980s, they needed something similar today. If you look at the HBO The Wire series, they compressed fifty years of Baltimore history into five years and just move things around, one in front of the other. The needle exchange program took place in the late 1980s in Baltimore. Mayor Schmock and his health commissioner had a difficult time getting that through. Once they got it through, they made a significant difference in saving lives, it also created an avenue you could get those who are addicted and contact with medical practitioners with other issues they were dealing with – from counselling to any other medical conditions they may have.

The creators of the show thought, “what could be as controversial as needle exchange?” So they came up with this idea of an arrangement with dealers, so they would stop shooting one another and make it somewhat more business-friendly. Maybe that’s a step in the right direction. Hamsterdam is the only part that was made up, but everything else was pretty much spot on.

***

Leszek Wieczorek is a retired police officer. He served as a criminal police officer in Bielsko-Biała and Katowice, both in Poland. He retired in 1999, and since 2010 is a member of LEAP. In his public speeches he advocates for drug law reform in Poland.

Neil Woods spent fourteen years (1993-2007) infiltrating drug gangs as an undercover policeman, befriending and gaining the trust of some of the most violent, unpredictable criminals in Britain. With the insight that can only come from having fought on its front lines, Neil came to see the true futility of the war on drugs: that it demonises those who need help, and only empowers the very worst elements in society. Neil is the chairman of LEAP UK, and has starred on Channel 4’s “Drugs Live.”

Major Neill Franklin is a 34-year law enforcement veteran of the Maryland State Police and Baltimore Police Department. During his time on the force, he held the position of Commander for the Education and Training Division and the Bureau of Drug and Criminal Enforcement. Major Franklin instituted and oversaw the very first Domestic Violence Investigative Units for the Maryland State Police. After 23 years of dedicated service to the Maryland State Police, he was recruited in 2000 by the Commissioner of the Baltimore Police Department to reconstruct and command Baltimore’s Education and Training Section.

***

Neil Woods: Police officers or anyone connected with Law Enforcement past or present, please get involved. So many of you will be well aware of the costs of this Drug War. LEAP is expanding, especially across Europe. We have to be listened to as we’ve been on the frontline. Together we can change the world. Email [email protected]

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)