“Tito is like a God to me.” Luka speaks the words with a slow, deliberate determination, his eyes narrow and focused, his hand thrusting forward to emphasise the point. He’s 23, a tall, thin, non-practicing Bosnian Muslim and a self-described communist. Along with his partner and a smattering of other guests drifting in and out of our Sarajevo hostel’s kitchen, we’ve spent hours rapt in political discussion fuelled by the city’s ubiquitous (and cheap) two-litre plastic bottles of Sarajevsko, the local brew.

Guidebooks and webpages abound with endless warnings about why not to bring up politics in the former Yugoslavia.

At first I thought a conversation like this would never happen. Guidebooks and webpages abound with endless warnings about why not to bring up politics in the former Yugoslavia. Specifically, they are referring to the string of wars in the region in the 1990s, a series of nationalist conflicts triggered by the collapse of communist Yugoslavia which left at least 140,000 dead and over 4,000,000 displaced (nearly 20% of the population). I took this advice on board. With the wounds so recent, it seemed reasonable enough. I hoped for a conversation or two somewhere along the way offering a small window into the local memory, but that was all.

Perhaps these columnists had failed to win over the trust of those they spoke to. Perhaps it was they who were the ones uncomfortable with the topic. Perhaps things have changed. Or perhaps they were simply wrong. But, with the noteworthy exception of men around the age of 45-55 – those most likely to have personally fought in the conflict – I found during my time in the region that talk of the war, politics, Yugoslavia and the past is rarely far from the surface. Nowhere is this more true than in Bosnia, the Balkans’ most multi-ethnic region and one still perpetually hamstrung by an immensely complex patchwork of government organisation hammered out to bring the war to an end: three presidents, three postal services, three electricity companies, three of everything, each divided up between the three main ethnic groups, Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims), Croats, and Serbs.

Not only are people willing to talk of the past, but their viewpoints are remarkably similar. The ethnic hatred of the 1990s – still so emphasised in the contemporary press – is nowhere to be found. And nowhere is any great remorse at the ‘failed communist experiment’ our schoolbooks teach us about. Yes, Luka is slightly more pro-communist and pro-Tito (the Yugsolav president from the end of World War 2 till 1980) than your average Bosnian. But only slightly. And his words chime with opinions I heard over and over again.

“Under Tito there were jobs. Under Tito there was social security. Ordinary, working people could take their entire families on holiday to the sea for 20 days at a time,” a Serbian friend informed me. There were trains, roads, housing, factories. There was international prestige. And most of all, for 45 years, there was peace and there was unity.

These opinions are pervasive throughout the region. Streets are lined with stalls selling everything from Tito coffee mugs to Yugsolavian flags. Sarajevo has three explicitly communist bars: one dedicated to Tito, one to communist Yugoslavia, and one to Che Guevara. Similar establishments crop up everywhere. Jajce, Banja Luka, Novi Sad, Belgrade. Until recently there was even a Yugsolavian-themed amusement park in Serbia. The old talk of those years with a mixture of nostalgia and pride, the young with admiration and longing.

The populations of five of the six republics of former Yugoslavia wish that it had never disappeared at all.

Nor are such observations merely anecdotal. In May of this year, the polling company Gallup posed the issue in the form of a simple, direct question. “Did the breakup of Yugoslavia benefit or harm this country?” About 60% of the region answered stating they believe it’s done more harm than good. Only 25% think the opposite.* Numbers are even more stark in poorer, non-EU states like Bosnia, where 77% regret the break up and only 6% support it, and Serbia, where the ratio is 81%-4%. The only fully independent state where the majority thought their country had benefited (by a 55%-23% margin) was Croatia. Kosovo, still locked in a seemingly endless sovereignty standoff with Serbia, also backed the separation. Overall, however, opinion is clear. The populations of five of the six republics of former Yugsolavia wish, to some degree or another, that it had never disappeared at all.

The key question here, one beyond the confines of the quantative methods favoured by polling agencies, is ‘why’. What is it about the old communist Yugoslavia that elicits such support, such passion, even among those too young to remember it at all? Liberals may point towards the residual effects of Tito’s mass cult of personality. They would not be wrong. To this day, it is often Tito, not the system as a whole, people mention. Tito provided jobs. Tito built the roads. Tito liberated the country from fascism.

Unemployment was virtually non-existent under Tito’s power.

However, this does not tell the whole story. Yugoslavia, like many communist states, offered good public services. There was free, high-quality education, pensions, healthcare and the like. Railroads and motorways crisscrossed the length and width of the country. Mines, factories, and farms provided stable, well-paying employment. Perhaps most fondly remembered were the short work days, long holidays, and early retirement (workers were eligible for a full pension at 60 and were usually transferred from manual labour to ‘advisory’ and teaching roles at 55). Unemployment was virtually non-existent.

Of course, collective memory is not infallible, and much of it is conditioned by the present. The former Yugoslav countries have long been in a state of permanently high unemployment and economic instability. In April, Slovenia became the first post-Yugoslavian country to reduce their own unemployment to the single digits: 9.8%. However, numbers remain much higher in other states, topping out at a mind-boggling 40% in Bosnia – a figure which includes approximately 75% of young people.

However, the raw economic figures don’t tell the entire story either. There’s something more ephemeral, more un-quantifiable going on. Sarajevo was once famed as a cultural epicentre. Bands, poets, writers, and actors flocked to the city from every corner of Yugoslavia. Today most of the former venues lay empty. The culturally ambitious hit the road in search of visas to Berlin.

More harmful still, in the eyes of many, was total breakdown in ethnic relations precipitated by Yugoslavia’s collapse and the subsequent territorial conflicts. Once upon a time, all the region’s ethnicities lived in relative peace. Marriages between families of different ethnic backgrounds were common, and the relative suppression of religion, though obviously a questionable, nonetheless smoothed out differences between Croat, Serb, Bosniak, and so on. “Brotherhood and Unity,” the official motto, was enforced rigorously, and nationalist sentiment crushed. The result was much anger and some bloodshed. However, it was also a state capable of uniting a half dozen (or more) historically opposed peoples.

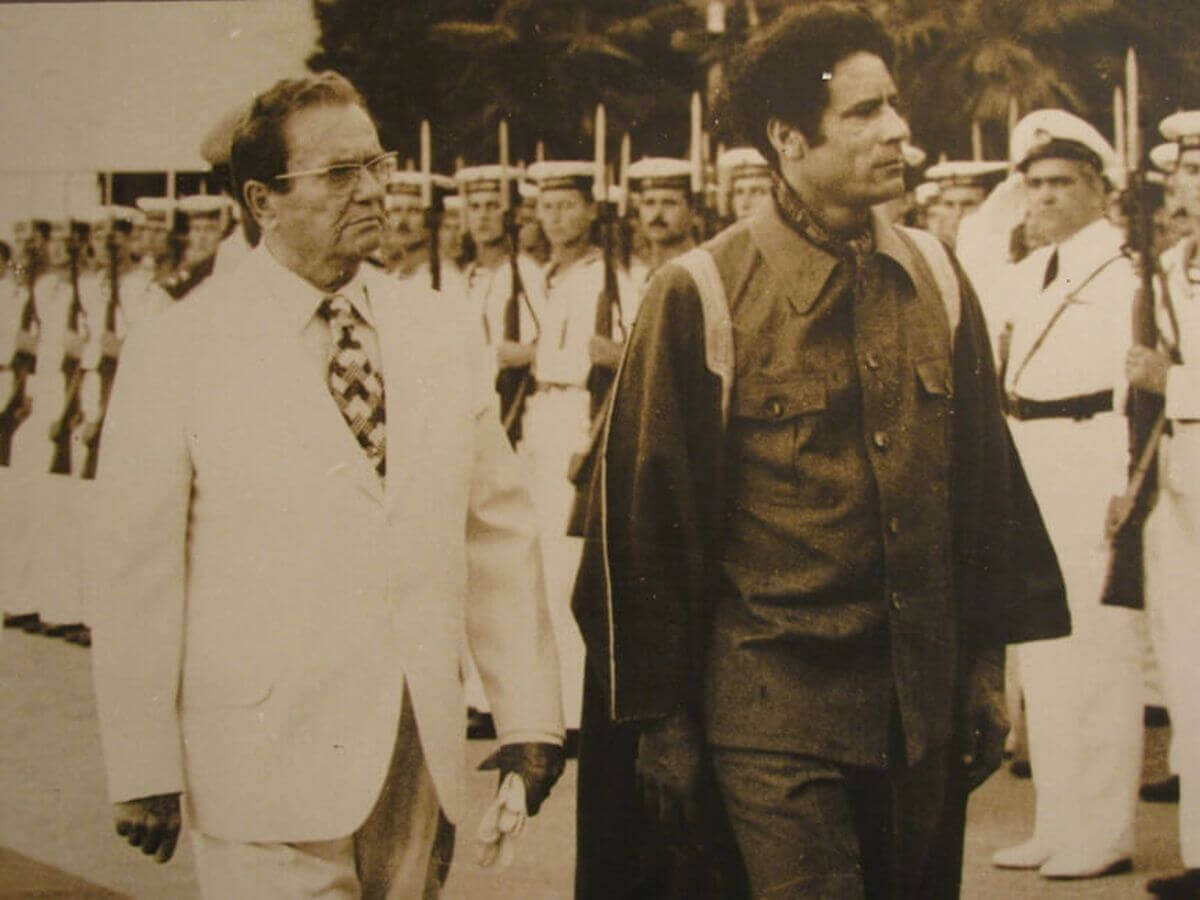

Finally, Yugoslavia “mattered.” The country founded the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), a Cold War bloc opposed to both Soviet and American influence, promoting instead anti-imperial, anti-colonial aims. Today the NAM contains within it 55% of the world’s population and over two-thirds of its individual countries. When Tito traveled he was often greeted by throngs of supporters and strings of newspaper articles. By binding their sovereignty together, Yugoslavia was able to count nearly 25 million citizens among its number. It became an icon of “Third World” defiance. Today, few outside the region can name a single of the country’s presidents, much less their foreign policy aims.

Influence-peddling, corruption, and backscratching were the only real root to power.

All of this does not excuse the very real oppression that occurred under Tito. Yugoslavia was, throughout its communist history, a one-party dictatorship. While economic and political democracy existed on a low level, influence-peddling, corruption, and backscratching were the only real root to power. Many may find the ethnic nationalism and religious conservatism of the right objectionable. However, Tito and his successors’ methods of imprisonment, as well as the suspected state-sponsored assassination of several expat dissidents, is far from a reasonable response. Suffering was real. This is no panacea and should not be treated as such.

Dreams of a good life: why the US election reminded me of Yugoslavia

However, talking to the people of the former Yugoslavia, hearing their opinions and understanding their worldview helps us move beyond the manichean, black vs white, good vs evil dichotomies painted for us by western opinion makers, politicians, and textbooks. The people of the former Yugoslavia do not long for dictatorship, nor for arrests, repression, and secret police. They do, however, long for a time when jobs were secure and well paid, when workers voted for their bosses, when social rights were respected, and when different peoples, of different faiths, with different histories could live side by side in peace and, to some small degree at least, “brotherhood and unity.”

“So do you think Yugoslavia will ever come back?”, I ask Luka.

“Never.”

I received the same response every time I asked this question. The pain and deep-seated mistrust generated by a decade of on and off wars makes such a reunion virtually impossible to fathom, no matter how much it’s longed for. With a political class that thrives off peddling old hatreds, this impossibility seems ever more clear. The question, a quarter century after independence, then, is what lessons can be learned from the past, and what kind of future can be built on its ashes.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)

“Until recently there was even a Yugsolavian-themed amusement park in Serbia.”

Oh, so they shut that down. I don’t remember reading any news on it.

As for unemployment during Tito’s time, you forget that many Yugoslavs went to Germany and other countries for work – the gastarbeiters. So Yugoslavia was exporting unemployment.

In fact, unemployment was a serious problem in the country. According to Woodward in “Socialist Unemployment” it even caused the economic disparity that tore the country apart. Further on, the “average Bosnian” is quite an imaginary concept. That may be ‘the’ right wing Bosniak (Bosniaks in total composing only 51%). Having read http://politicalcritique.org/cee/2017/azarova-uk-media-eastern-europe-western-representation/ , I’m quite negatively surprised to find such an article on this portal, I must say!