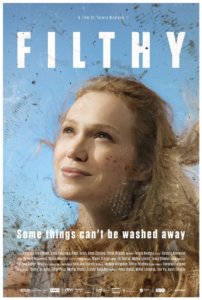

The Slovakian director Tereza Nvotová’s new film Filthy has just been released in cinemas. Set in Bratislava, its theme is the rape committed of seventeen-year old Lena by her mathematics teacher. The movie debuted at the film festival in Rotterdam and is Nvotová’s first foray into the field of feature film, after having made the documentaries Jesus is Normal and Mečiar (the latter currently being made into a full-length movie for HBO).

Below is an interview by Apolena Rychlíková with Tereza Nvotová about her upcoming movie Filthy.

Filthy took several years to make. The filming took place throughout 2015 and 2016. What was the most difficult part of the process?

The worst thing was not knowing whether anything will come out of it when we already invested a whole lot of time into the project. The financing came from different sources at different times – and some of them simply did not deliver. In this phase, my job as the director was to keep believing in the film and convincing everyone around me that all this will eventually result in a finished movie and not just a waste of time, money and energy – all while knowing it may not. Keeping up this facade for multiple years was really hard; I’ve got to say, after living through the process of making a full feature film, I have a lot more respect for anyone who manages to see this through. Finishing even a stupid movie takes a lot of work.

The central theme of the film is rape. In the Czech Republic, on average ten per cent of the women have experienced it and in spite of that, the stereotypical myths about rapists and women holding their part of the blame for it persist. While there has been some discussion lately, the film industry seems to avoid such important topics. Why?

Rape is being either overlooked or made light of, laughed at. You hear rape jokes everywhere – even from politicians.

Rape is being either overlooked or made light of, laughed at. You hear rape jokes everywhere – even from politicians. That has to account for at least a part of the way rape is perceived.

Regarding film: I do not know whether it is because most screenwriters and directors are men, or because the people who use rape as a dramatic turn in their stories have no experience with it themselves. But treating rape lightly is a horrible practice, especially towards people who lived through it. We cannot tell them, “It is just a silly Czech comedy, it does not matter.” These things are traumatizing and need to be worked with, above all else, sensitively. I think filmmakers make a mistake here: instead of helping give this topic the gravity it deserves and taking part in discussion of it, we tend to do the opposite. And sure, it does not have to be all tears, but mocking or downplaying it adds to the shame many victims feel, a shame that prevents them from talking about it. If I tell a man that every tenth woman in this country was raped and thus he probably knows one, he will just shrug and say he does not. Sure – because a whole lot of women never tell anyone, much less go to the police and bring it to court.

Barbora Námerová wrote the screenplay, making this an unusual phenomenon in the Czech Republic: a film where both the authors are women. We are used to male authorial duos – Hřebejk-Jarchovský, the father and son Svěrák and so on. Gender inequality or discrimination in the film industry is generally not discussed in the Czech environment, despite Hollywood trying to deal with it for several years now. How do you feel as a woman in the world of filmmaking?

I’ve got to say I feel good – but that could be caused by simply not taking notice of all the opportunities one does not get: when someone decides you are not the right person for the job, they usually do not tell you. It is hard to come up with an objective assessment of the way things really are – this is really a question for the men who make these decisions.

But I am surprised by the success women filmmakers are having in the last couple of years. Apart from us, there is Iveta Grófová or Mira Fornay – and that is with Slovakia, an even more sexist country than the Czech Republic, with key positions often held by men older than sixty. But women bring their films to international festivals.

My motivations were anger at society for keeping quiet about rape or making light of it, and to attempt to dispose of myths connected with rape.

It is a paradoxical situation. Back when I was working on the movie, male members of the Audiovisual Fund kept telling me to forget about rape and make a comfy, friendly movie about having sex for the first time. That it would make for a nicer film. But I was never laid off the project I was in the middle of working on just because I am a woman.

Going back to Filthy– what would you say was your primary authorial intent?

My first motivation was anger at society for keeping quiet about rape or making light of it. Plenty of people around me have experienced it and never said anything. And I can understand that, the system, the society just does not allow it, not even on the family level. When a women says she was raped, she immediately becomes “the victim,” a label that spreads and becomes impossible to get rid of. And I get why women do not want to be in this situation. In this regard, the entire code, the entire filter we perceive rape through has to change. And that was my main reason.

Another one was to attempt to dispose of myths connected with rape — that it only happens at night, to drunk girls, that instead of the question who did it, people concern themselves with whether she provoked him, and so on. This kind of discussion is utterly absurd; we should not ask whether the victim provoked the perpetrator of murder! With rape, the position of the victim is always put to question, because there is this weird myth that a man cannot be held accountable for his actions while he’s got a boner. That it is not his fault, it is like being on drugs and he is not to blame when he does something wrong.

And this view needs to be changed. That is why the film takes place in a seemingly safe and secure setting. The protagonist is raped at home, in broad daylight, by a teacher she likes and trusts. Statistics tells us this is often the way it happens.

The moment rape occurs in your film, a whole new universe of institutions that are supposed to help but do the opposite appear. Do psychiatric clinics really work the way you depict them in the film?

That is another topic connected to it. We would not dare to put something too far removed from reality into the film – it is, naturally, poetic license but based on true stories of people who went through something like that. We definitely did not want it to be an anti-psychiatric movie, we are not saying that doctors want to hurt someone.

We would not dare to put something too far removed from reality into the film – it is based on true stories.

But the system is set up badly. There is not enough money, staff are burned out because they are stuck with way more tasks than they could possibly handle, and/or the staff is not properly trained, and so on.

The children that end up in psychiatric clinics often keep coming back to them. And they often come from children’s homes which suffer from similar problems – they are underfinanced, short of staff capable of doing this emotionally exhausting work. It is all connected. One film cannot deal with every facet of this problem, it is not a scientific paper; we wanted to show how the people inside this system that have little or no means to express their views on the situation experience it. This laxness can lead to horrible things. And the sad part is that many people – patients included – really need so little to be heard, to be understood.

One of the key leitmotifs of your film, at least to me, is trust. Trust in yourself, trust in the people around you, trust these people in institutions who are supposed to provide help and professionalism. These motives keep reoccurring and developing in your film – a good example would be the story of the protagonist’s parents who go through a massive change in the course of the movie.

I am glad you interpret it this way. This is really a film about what happens when the most basic, fundamental trust is broken by a brutal act like being raped in your own room by someone you completely trust. This unavoidably damages your trust in everything, everyone else, especially in a world where something as fragile as trust is easily replaced by distrust just because you cannot say something. That is the position of the parents: they want to help their daughter but they do not see into their children’s lives. And so, unintentionally, they make the situation even worse.

Some reviews talk about the film being used as a base for „awareness activism.“ Is it even possible to make a good movie on a topic this serious without creating social discussion?

It is utterly absurd to remove film, or art in general, from the reality we live in.

I do not understand that bit of criticism, either. How does one build “awareness activism”? People keep asking me why I chose this topic and I tell them that it is a problem experienced by many – too many – women in our society. It is utterly absurd to remove film, or art in general, from the reality we live in. I approach it from the opposite angle: go from reality to the movie, and use it to reflect a real issue, something I find wrong with the reality. Why should I make films about something that has been solved and will not raise any emotions in anyone? If I did, I would lack the drive we talked about earlier – believing in the importance of the film because you owe it to society. You want the viewers to find out about what is going on.

Maybe I view film as a medium in a different way from what is usual in the red-carpet world. For me, it is communication with the world, and when I am talking to the world, why should we just shoot the shit?

Filthy debuted at the prestigious film festival in Rotterdam. What was the contact with the international film industry like? Did the topic of rape resonate even outside the Czech Republic and Slovakia?

The contact was great! We knew from the beginning we are not making a movie for hundreds of thousands of people, that is simply not how this topic works. But we knew we could aim for the festivals and viewers abroad. Rotterdam showed that the issue our film deals with is important for the whole of Europe – I was actually surprised with how much attention our film received, since a lot of films are screened there for the first time, and they are provocative, weird films. And Filthy filled the cinemas, sparked long debates, the magazine Variety picked as one of the seven films from Rotterdam they wrote about. The sad part is that this shows that sexual violence is a problem not limited to our countries, but we are still glad that we can talk about it abroad. I have no idea if it is going to help anything, but I think we can consider the fact that someone is reading about it right now as a success in its own right.

Translated by Michal Chmela.

This article was created as part of the Network 4 Debate project, supported by the International Visegrad Fund.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)