The Vice-chairman of the Czech Association of Exporters, Otto Daněk, recently gave an interview in which he proposed dividing university courses into “useful” and “useless” fields. In addition, he would like to structurally discriminate against these “useless” fields of study by enforcing fees. This is hardly a surprise – it is just the latest attack on the humanities and wider education system by a representative of the industrial sector, similr to President Miloš Zeman’s support for vocational training.

Industry representatives are all-too-obviously demanding greater economical control over education – and this threatens its autonomy.

The primary argument presented by this faction is that such a move will emphasize the economic importance of technological fields of study, leading to greater competitiveness in the field. In light of the secondary sector becoming increasingly precarious, caused by minimizing expenses by outsourcing production to less costly countries, a question arises: why would we even want to aspire to this vassal position of generating an army of badly-paid and unqualified laborers? Turbulent technological advances do not work to this approach’s advantage either: both the ongoing automatization of work that brings job losses and the emergence of new (as well as the disappearance of old) fields of work contribute to higher unemployment among technical students. The result is a paradox that paints a rather unflattering picture of the ideology of “usefulness”: those rallying against unneeded education and useless graduates end up being unneeded and useless themselves. And listening to their advice produces more and more graduates with no hope of finding employment in their chosen field.

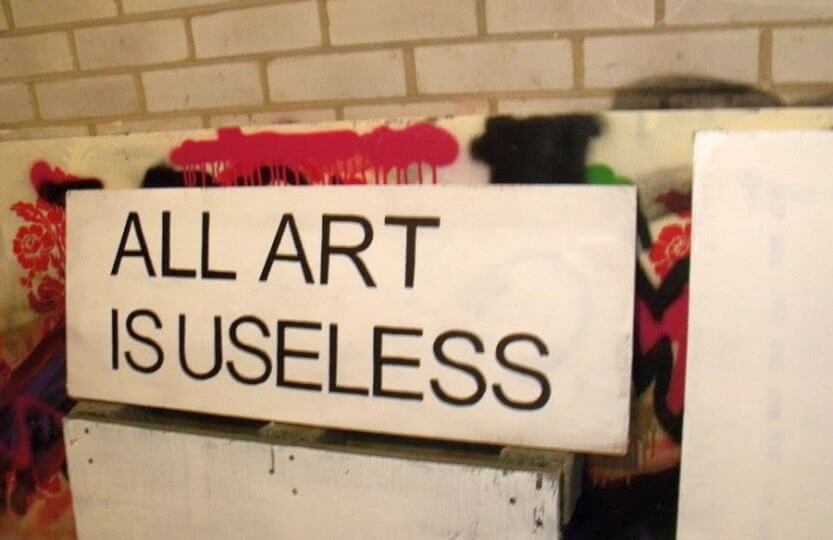

Industry representatives are all-too-obviously demanding greater economical control over education – and this threatens its autonomy. The measures they are calling for would force universities to produce human resources in accordance with the demands of the secondary sector– demands that can and do fluctuate. This further reinforces the theory that capitalism does not, in fact, need democracy to operate; that it merely slows down the smoothly working cycle of inhuman – and dehumanized – substance. The proposed measures would attack the plurality of fields of study, threaten the further development of society and lead to cultural stagnation. Besides, we can just as easily observe the issue from a different perspective – for example, by thinking about education in arts, its self-reflection and its radicalization.

The right to remain idle

The primary problem of education is that it is widely understood as preparation for the future. By this logic, the autonomy of the academic environment is just an obstacle – as is just about everything not directly connected to institutionalized preparation for future economically beneficial activity. Whatever it is, if it is not related to work, it is superficial, futile and disposable. Speaking in terms of needed and unneeded fields of study, the stance of those who champion the study of arts (with the possible exception of design) is clear.

The time we spend studying in our lives needs to be reframed as a gift from the state – a gift that is not conditioned by regular outputs.

What I want to defend here is university education in free art, education viewed as open space for trial and error, for attempts, for play – but also for idleness and mind-wrecking boredom. One of the approaches of contemporary arts education is built around limiting the forcing of tasks, supervision and goals onto students as much as possible, resulting in more free time to spend in the studio. A studio or school designed around this approach becomes a sheltered asylum of sorts – not an asylum for the mentally or physically challenged, but a place that offers both technical facilities and institutional protection, reassuring student and demanding the minimum. In other words, the time we spend studying in our lives needs to be reframed as a gift from the state – a gift that is not conditioned by regular outputs.

Even a relatively liberal system like this needs to be subjected to criticism. We cannot stop looking for alternatives and viewing the practice of art education through the lens of arts practice itself; after all, the very concept of education in art – and the absurdity of requiring a qualification in something as intangible as art – is paradoxical . In addition, some of the existing mechanisms of education – such as the institution of a workshop leader – are very prone to concentration of power and its subsequent abuse based on personal and sometimes intimate relationships between teachers and students.

In this regard, it would be helpful to remember the Non-Utilitarian School: a project by Blahoslav Rozbořil and Josef Daněk that originally took place in the late eighties and was revived in 2010 with the help of Barbora Klímová. The trio’s Dadaistic workshops, which teeter on the border between sociology and performance art, claim to pursue “the cultivation of a useless human”, resulting in a person not prone to being abused by the machinery of a pragmatic social order. Both the undermining of instrumentality of education in favour of purposeful superficiality and parodic examination of its functioning can work as a healing agent – as can the critical voices aimed at the institution of the workshop leader. As the recent Fourth Wave initiative showed, the institutionalized sexism present in the Czech educational system is a consequence of the little-reflected-upon power relation between teachers and students. So, in addition to an autonomy of time, it is also necessary to demand critique of the workshop leader institution.

Love of non-contribution

There are at least two groups that relativize the top-down approach to education and create alternatives to it in the Czech Republic. I am talking about the Studio of Pavel Ondračka in Brno and the Studio withtout Master project in Prague. The Atelier of Pavel Ondračka is an extension of the harsh-noise band “Pavel Ondračka” (named after an unpopular professor of art history) and it follows the hacktivist spirit of the band: its primary agenda consists of open workshops and lectures. Thanks to the studio’s open format, anyone can join and create within its framework, encompassing things from Arduino workshops to DIY tattoos and free improvisation.

In contrast to the Studio of Pavel Ondračka’s openly parodic nature, the Studio without Master project presents itself as a more serious alternative to the standard, vertically structured art studio model: it is structured along a horizontal dimension. It stresses the need for regular meetings, consultations, discussion and confrontation of works and approaches. It is a platform that seeks to challenge the compulsory studio education with spontaneous mutuality.

The education of artists needs to assimilate what art is in itself: a radical expression that pays no heed to benefit, a mutual dialogue with value expressed in the refusal to submit to the pragmatic goals of late capitalist society. This intentional and systematic uselessness needs to be cultivated in order to create the time and space for autonomy: if there is a place for the Modernist ideal of unity of art and life, it has to be in the conditions of self-reflective education in art, undertaken for the love of aesthetical experience – so often perceived as a category of uselessness.

This text originally appeared on A2larm. Translation by Michal Chmela.

This article was created as part of the Network 4 Debate project, supported by the International Visegrad Fund.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)