Interesting times have come upon Slovakia: while the mass gatherings marking one year since the murder of investigative journalist Ján Kuciak still chanted slogans protesting against the rule of the SMER-SD party (social democrats in name only, in reality your garden variety populists with a conservative bent), they only served as a sad punctuation of the fact that nothing really happened apart from the resignation of the then-PM. Robert Fico, apparently finding himself with nothing to do, decided that ruling the country should be followed up by being appointed a judge of the Constitutional Court, after having brilliantly convinced the Parliament that 13,5 is, in fact, more than 15 when it comes to the required number of years spent working as a lawyer. Almost immediately afterwards, the genius mathematician’s judicial career was nipped in the bud by the current President, who – not unreasonably – pointed out that the function has a moral dimension and a man forced to resign amidst mass public protests concerning the process of investigating a murder, might not be the best candidate for a judge. Fico responded by having his party boycott the nominations of all the other candidates, leaving the Constitutional court effectively paralysed as the four remaining judges is a number insufficient to reach a verdict on most issues. This might pose some problems, as the Slovaks are about to elect a new President and the Constitution’s wording regarding the amount of votes required to win the first round is unclear. And the only one with the authority to re-interpret that is, you guessed it, the Constitutional Court, currently lacking the manpower do anything about the mess, thanks to a vengeful ex-PM. Interesting times, interesting times.

Flavors of disaster

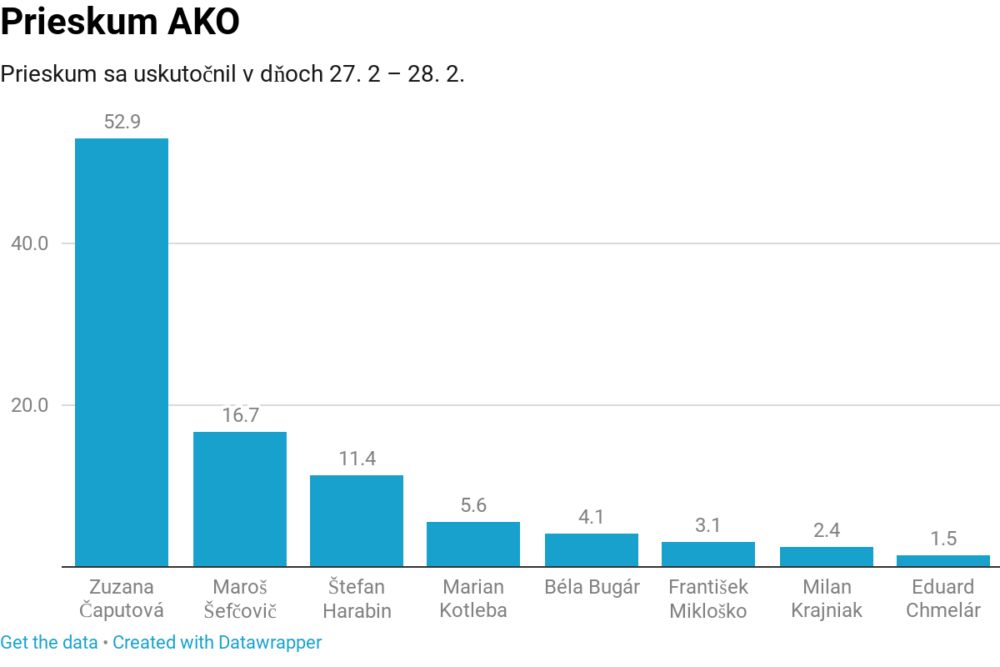

While the chances of an election being decided in the first round are extremely low – actually it has not happened in Slovakia ever since it switched to the President being elected directly by the people – there are indications that it might be relevant; to wit, surveys:

(Survey from 27.2.-28.2. 2019. The required amount of votes to win in the first round is 50%… theoretically, see Constitutional Court. Oh wait, you can’t.)

But before we get into just who that Čaputová woman is anyway, and how the hell she managed to suddenly outrun all the fan favorites, we should take a look at some of the runners-ups – because given the current situation, at least one of them will end up in the second round, and they are all various flavours of disaster.

Marian Kotleba should not need any introduction: what is needed, but alas is not within the author’s power to provide, is a reasonable explanation of how the hell is a card-carrying, uniform-wearing neo-Nazi being seriously considered a Presidential candidate. His five percent in the polls does not look very threatening but the problem lies in his next door neighbor in the graph, Štefan Harabin, who espouses very similar views, but wears a suit while doing it, so apparently it’s OK.

Harabin is a fascinating character, really: cursory search reveals his claims that having a goat as a mascot of the charity NGO Človek v ohrození is actually sophisticated subliminal Satanist iniative to dissolve morals (words all his) or that World War 2 was started by the Anglo-Saxons who drove Hitler to attack Russia (never mind Molotov-Ribbentrop or the hideous nationalism underlying his division of people into Slavs and Anglo-Saxons). In the current political climate, the fact someone listens to this clown is not the surprise here: the real shock comes from the fact this clown is not, in fact, a clown. This clown is, in fact, a judge.

Their problem when it comes to the upcoming Presidential election is that on a lot of issues, Kotleba and Harabin are interchangeable, and this is likely to occur to their voters as well. Should either of them enter the second round, they could both – Harabin a bit more likely than Kotleba – rally the more conservative part of the electorate despite having thrown their lot in with other candidates in the first round.

That leaves us with Maroš Šefcovič, quite possibly the establishment incarnate. A lifelong politician, diplomat and bureaucrat, he is the candidate pushed by the ruling SMER party, which should be sufficient for all sorts of alarms to start ringing. While Šefcovič claims that he is not a member of the party, he has no qualms accepting their money – a fact that could easily be turned into leverage. Unlikely to possess strong opinions on home politics, he should at least be able to step in the way of nationalistic anti-EU sentiments. Or not. Depending on the leverage. But he claims to be a socialist…

So who is that woman anyway?

Zuzana Čaputová’s rise to fame begins with the fall of another candidate, Robert Mistrík. Their campaigns both targeted city folk, liberals and intellectuals; they both focused on criticizing the ruling SMER-SD and pointing out the risks of giving more power to the party via a pliable president. After some clashing, Čaputová managed to overtake Mistrík in the surveys; Mistrík, uncharacteristically for this slice of the globe, withdrew his candidature and appealed to his voters to vote for Čaputová. And that brings us where we are now.

52% is an optimistic estimate, especially for a liberal candidate in mostly conservative Slovakia. But there are several factors playing in Čaputová’s favor. One, people are disillusioned with the current government as the Ján Kuciak anniversary protests showed, and Čaputová has no connections to that. Her biggest claim to fame before the elections was environmental activism, specifically (and more shockingly, successfully) fighting against an illegal landfill built by a business connected to both SMER and Kuciak-implicated businessman Kočner – according to her website, anyway. Two, she is potentially acceptable to voters who do not necessarily share her views but are rightly terrified of having their country represented by a conspiracy freak or a neo-Nazi. Three, she is the only candidate openly supportive of minorities; such trustworthy sources as the Czech mutation of Sputnik frequently accuse her of such horrible crimes as supporting LGBT equality and pro-immigration propaganda.

Of course, this can hurt her – as can being a divorced woman in a mostly conservative country. And, one really can’t have it all, she is no leftist. But that might not be a bad thing in this case.

See, the President of Slovakia is purely representative (unless they pull a Zeman, may his hemorrhoids explode, and start overstepping their authority), and a lot of their power is the power to draw attention and open public discussion. Slovakia needs this; we’re talking a country that has decided to incorporate the frankly medieval „traditional“ definition of marriage into its Constitution as late as 2014. A President sympathetic to the plights of minorities could finally draw out the issues “we just don’t talk about,” like discrimination against minorities, to public attention – kicking and screaming, if necessary.

And, after all, she appears to be the least evil of the bunch.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)