Łukasz Ronduda: You were the first to follow Piotr Uklański and make a move from visual arts to cinema. Was it a successful move?

Anna Sasnal: I think the problem with that move was largely about the fact that it should have taken place in the opposite direction. It’s cinema that should open up to art, and not the reverse. To make good films, you need to expand your field of experience to cover not only what you can see at the gallery but also, for instance, literature.

ŁR: In 2012, you did not agree to show It Looks Pretty from a Distance (Z daleka widok jest piękny) at the festival in Gdynia. Why? You didn’t consider yourselves to be part of Polish cinema?

AS: We thought it was not a good place to show that film. We showed it at the festival New Horizons. The festival in Gdynia is largely about the film industry. When we received the award for It Looks Pretty… some people said it was an “on-the-job accident” because “we are not part of the industry”. If we’re not, then we won’t be forcing our way in. If a mussel doesn’t open, don’t eat it.

Jakub Majmurek: And later, during the recent years, have you had any more opportunities to meet the industry? Did any filmmaker come to you and say: “I don’t entirely like this but I can see some interesting things here”?

AS: Apart from Joanna Kos-Krauze, none of the filmmakers told us anything good. She was the only person we talked to about it. Ula Antoniak invited me to an expert committee at the Polish Film Institute (PISF). Before that, I had been reading texts submitted to Ha!art and I think I managed to come across a few interesting things. I thought I’d find something interesting there too, some potentially interesting cinema that is currently kept from growing.

JM: Was there anything?

AS: I’ve read quite a lot of scripts – but nothing.

Wilhelm Sasnal: After meetings with filmmakers I have the impression that they know much less about culture than people from the art world. Quentin Tarantino is the pinnacle of avant-garde.

AS: That translates into the fact that their greatest dream is to tell a story. If a story comes together well, it’s already a success. Filmmakers are interested in making films, and they care less about cinema. Count the filmmakers who come to New Horizons and see what’s happening in world cinema. We also had a meeting in Łódz with students of film editing. We watched and analysed Parasite (Huba) with them. I was astounded by the resistance that the film provoked. One of the guys said with malicious satisfaction that we’re free to show such a film at a gallery. For him it’s not a film at all, it doesn’t live up to what he expects from a film, it does not stick to the rules that they teach him at the Film School.

We had a meeting in Łódz with students of film editing. We watched and analysed Parasite (Huba) with them. I was astounded by the resistance that the film provoked. One of the guys said with malicious satisfaction that we’re free to show such a film at a gallery. For him it’s not a film at all.

JM: What rules?

AS: There is no “transformation of the protagonist”!

WS: Those young filmmakers should watch the film Essential Killing by Jerzy Skolimowski, who is already an older director. He also breaks all those rules. And that’s a film! You can criticise it but it really stands out among films produced in Poland. It makes a certain bold step.

AS: But Skolimowski is also a poet and a painter.

ŁR: The film school teaches them a certain machismo, a confrontational attitude. The further they go in their careers, the worse it gets.

WS: I have to tell you that I can’t stand that machismo of the film industry. I couldn’t work on a film set ruled by a bunch of testosterone-pumped guys rule.

AS: If we were to accept their criteria, then books could be written only by graduates of Polish studies.

JM: Polish cinema did not recognise you as a part of it?

WS: No, but I guess we don’t want to be recognised as a part of it.

JM: For you, Wilhelm, it might be a peculiar experience because you hold a major position in the field of art. When you move to cinema, your position becomes marginal.

WS: And I appreciate that position a lot. These two worlds are completely incongruent. Painting is very intimate. A director is expected to be a public figure. The film industry is a “who has a bigger dick” competition – if you’ll pardon the expression. We don’t want to take part in that competition. I need to tell you one more thing, for me shooting a film that costs twenty, thirty million to make is something immoral in a country like Poland. I feel sympathy for directors who work with such budgets. What is a director supposed to do when he’s not happy with what he’s made? He cannot mothball a film for twenty million. We’re free to do that.

JM: Are you happy with the reactions that It Looks Pretty… got from the audience?

AS: Yes. We had a number of good meetings, discussions of a rather publicistic kind, but the meetings were small and mostly attracted those who had already been enthusiastic about the film. Although it also happened that some people sassed us.

WS: I was very positively surprised by what happened, for example, at the New Horizons. By the conversations that were held there. We’re still groping our way through the world of cinema. We don’t have any illusions that these films will sell well enough to give us income. That’s why we’re happy that the film screened at cinemas at all. When we were shooting it, we completely didn’t think about “what’s next”. Our film editor, Beata Walentynowska, told us “send it to New Horizons.” And that’s how it began, a little bit by chance.

JM: What’s your opinion about the reactions of critics?

WS: I have to admit that I was astounded by the indolence of many critics who didn’t understand at all what the film is about.

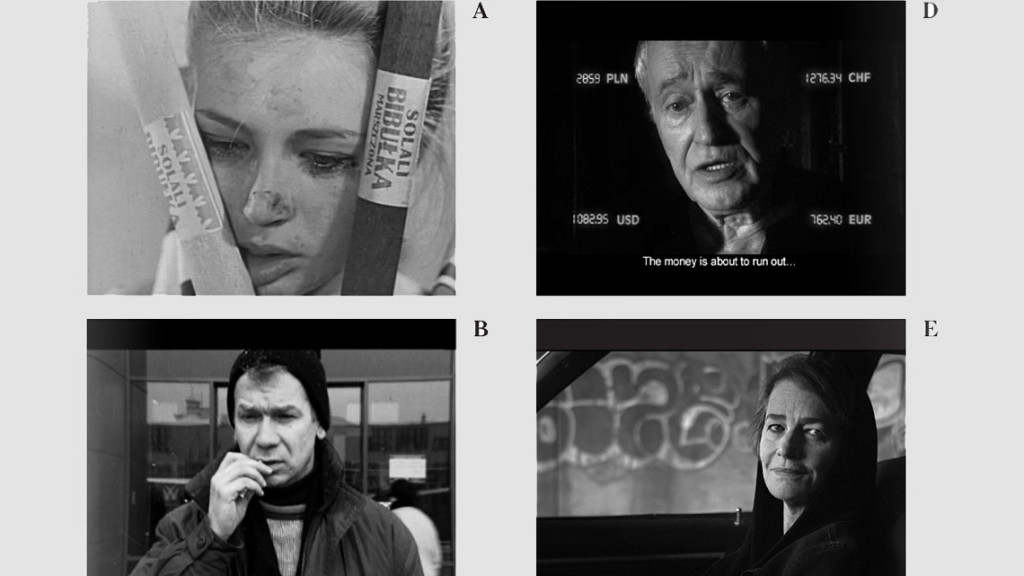

JM: Parasite is your second feature-length film that screens at cinemas. What has changed since your debut in terms of production? Are you becoming more professional?

AS: I guess not (laughter).

WS: We shot some more films. The first bigger production was Swineherd (Świniopas). Then we made The Fallout (Opad). We shot it with a big professional crew. It was our most professional production. We weren’t satisfied with the outcome. But it has some potential, so maybe we’ll return to that film one day. I even had an idea to get those actors together, several years older, to shoot some extra scenes with them and mix these scene with the older footage.

AS: And I have the impression that for us It Looks Pretty… was an escape from The Fallout, we wanted to make a completely different film. Parasite is a bit of a return to what we wanted to do when we were shooting The Fallout but we didn’t manage to achieve.

WS: Yes, but the film set in Parasite was smaller. I don’t feel well when the set is big. Especially that I am the cinematographer and need to wait with the camera until everybody else is ready.

ŁR: I met two film professionals who worked on your film set. Not only they didn’t complain that you were not professional enough, but they even absorbed your way of working. For example Kuba Czekaj – I attended a course at the Wajda School with him and he was telling me all the time about how he had been working on It Looks Pretty… He was impressed by the freedom on the film set; by the fact that there was no rigid division of duties, no rigid schedule of the day. He told me that when Wilhelm happened to see birds that were flying away, he was following that view, shooting it on camera, while the entire work stopped for a while.

WS: Yes, that’s true, that’s how it looked like.

AS: But we’re also very focussed when we work on the film set. So there is a schedule, but it’s open enough to leave room for situations when Willi can go away somewhere with his camera. In Parasite our working method was that we were shooting a number of scenes with Mr Jerzy and then locking ourselves for a few hours with the sound mixers – Igor Kłaczyński and Janek Rey – and the entire crew was waiting for us. Our work often has a very homely character. It’s like outworking. Especially with our film editor, Beata Walentynowska. She would edit both films in her little studio, then she would come to us for two or three days and we would work at our place. We would cover the windows with blankets, after all we don’t have a darkroom.

JM: The three of you edit your films?

WS: Anka’s presence in editing is much stronger than mine. I completely lose the tension, the dynamics. What I like most is the beginning of the film and the time when it’s ready. After working on the film set I have no power to do work. Anka loves editing. She’s also the one to write down the initial ideas for a film.

AS: For me, the first day of editing is a holiday. That’s when I begin to feel that I’m actually making a film. I suppose that’s the way you start writing a book.

ŁR: Wilhelm, you are a director-cinematographer. In what ways are you different from a director-screenwriter, a typical figure in Polish cinema? How does your profile influence the process of directing?

WS: For sure, I don’t lose interest in the question of acting. If as a cinematorapher I can see that something is fake, then it happens sometimes that I move the camera away from an actor’s face, take the head out of the frame. That’s when I focus on a certain detail to cover it. Cinematography is very important for me. The fact that I carry the camera, a heavy object on my arm. As a viewer, I have always enjoyed shots when the camera follows the actor. In such situations I always imagine a man who carries that burden and follows the person. In turn, I hate cinematographic styling. For example when the camera trembles in an artificial way. Because the protagonist is nervous. I totally don’t buy it.

ŁR: What is the relationship between your painting and your cinematography?

WS: In this respect I often think about new realism in the painting of the 1970s and overwrought film shots from cinema. For example in Man of Marble (Człowiek z marmuru – film by Andrzej Wajda from 1976 – transl. note). The wide-angle shot when Krystyna Janda places her leg in Jan Łomnicki’s car to block the door from closing.

AS: I think that the fact you’re the kind of painter you are has a great impact on the way you work with the camera. But it totally doesn’t work that way the other way round.

WS: Yes, there’s rarely any influence. From painting to film, but not from film to painting. After all, painting and film are two separate kinds of practice. The question of time is of key importance. It doesn’t exist in painting, you can stop viewing a painting at any time. You can’t leave the cinema all that easily.

Painting and film are two separate kinds of practice. The question of time is of key importance. It doesn’t exist in painting, you can stop viewing a painting at any time. You can’t leave the cinema all that easily.

ŁR: Cinematography is often described as a continuation of classic painting. Cinematographers themselves see it that way. When I started working with my cinematographer while making The Performer (Performer), I needed to recall the categories that I learnt about as an art history student but I wasn’t using as a person who deals with contemporary art: composition, chiaroscuro, and so on.

WS: Nobody among my fellow painters talks about composition. Cinematographers haven’t trashed the image in their field and keep thinking in such categories. I don’t.

JM: Is there any connection for you between Parasite and It Looks Pretty…? Or are you treading on a completely different territory?

AS: In It Looks Pretty… there is a character of a pregnant woman, a clerk in a shop. This actress is Joanna Drozda, who plays the main role in Parasite. This thread was way more developed but we dropped it during the editing.

WS: There was supposed to be a scene where the woman is looking after her baby, does the ironing and watches TV. The baby starts to cry and the woman turns the tap on and turns the volume up on the TV to mute the crying. In the next shot, we see her shaving her intimate areas, and the sounds of the TV and the water from the tap mute the crying baby.

AS: So the main thread from Parasite was taken from It Looks Pretty… At the premiere of It Looks Pretty… we met Joanna and told her that we wanted to make a film with her about a single mother. To strike a balance we also needed another thread, another protagonist. Hence the character of the elderly man.

JM: In It Looks Pretty… your work on the film began with Anka’s poem that is said to have been one page long. Did everything begin with your text in this film too?

AS: The first text for It Look Pretty… was slightly longer than one page, we used it to begin our work with actors, then I divided it into scenes. It was the same with Parasite, although the first version seemed too enigmatic even to Willi. But the first sentence of this text, “Only a fragment”, left an imprint on the entire film both in formal and content-related terms. When I write, I look for such concepts, words, sometimes single sentences that will make it possible to build scenes or images around them.

ŁR: What did your work on the film set look like?

WS: It was a massacre, afterwards we were totally exhausted. After both our work on the film set and editing. We gathered tons of footage, it had a quasi-documentary character – so whenever something interesting happened on the set, I immediately turned my camera on. Some scenes from the film hadn’t been in the script at all.

AS: It was hard work. A small set, fifteen people. Everybody performed a few functions at the same time.

JM: Are you satisfied with this film?

WS: I simply don’t like this film. But now, when already after Berlin we made some final touches, I watched it again and I have to admit that it drew me in. I can feel that after Parasite I have reached a limit. You cannot go any deeper, at least I can’t. For a long time I was poisoned with the vitriol and sadness that the film left in me.

ŁR: You don’t enjoy the protection that a professional film set offers, you don’t have units in charge of production. Because of this you are exposed to all kinds of emotions that accompany shooting a film. And it brings you closer to a documentary form.

WS: It also causes conflicts on the film set. For example between me as a cinematographer and Igor, the sound mixer.

JM: How long did the editing take?

AS: Almost a year. When we were finishing the editing we came back to the initial text. To the first sentence.

ŁR: Even though you’re very close to your protagonists, the film doesn’t empathise with them, the viewer observes them from a distance.

AS: This was our premise. We didn’t want the viewers to feel mercy or sympathy. We’re very close to our protagonists, but it’s always only for a short while. We see a fragment of their reality, their world, their bodies.

WS: These protagonists also love themselves in the same way that the camera that sees them. They see themselves like in a mirror. Looking in the mirror, she cannot like herself. She has an ambivalent attitude to her child.

ŁR: Polish cinema would immediately look for something for the viewer to hang on to.

JM: Cinema based on the mechanisms of projection-identification gravitates towards empathy by its very nature.

ŁR: The lack of empathy is what brings you close to structural cinema. But the same things that happened in structural films happen through the medium of the human being in your film. That impossibility of coming to like the protagonists is also based on social class. You look at them from beyond the class that they belong to, a class that you cannot get to like and believe that this class can get to like itself.

WS: We feel part of that world. We didn’t have the feeling that we were creeping into an environment. I’ll tell you even more, I think we could pick such an observation point and I wouldn’t call it class-based for the very reason that we come from there. It was a bit different than in It Looks Pretty… We went to the countryside, we worked with local people, they acted as extras, but the countryside provided a setting for our story. It was important for us to show what was happening in the past. But also to extract the cruelty that remains within each and everyone of us, without adopting a “we’re above it” position.

ŁR: The shooting stage, when you are very close to the protagonists, is something different from making a composition for the viewer, a composition that is, after all, very unempathic. There’s deep honesty in the fact that you show Parasite on such occasions as the hipster festival New Horizons and you tell the viewers: no, don’t pretend that you have something in common with this world. This is not a film that will ease your conscience. The chasm between your world and the world that we show in this film is so huge that you’ll never be able to really understand it. It’s very cruel but at the same time very honest.

AS: The title It Look Pretty from a Distance is exactly about this. And besides, it’s very tempting to scratch a scab. Especially a dried one.

WS: In Parasite, we expose the viewer to an emotional clash. The vision of an illness, a baby, a breast-feeding mother does not trigger the feelings that you expect it would. Instead of tender emotions there’s disgust. It’s not a comfortable position for the human being, for the viewer.

AS: During New Horizons I had workshops with female teachers and I noticed that they had a strong need to look for moments to identify themselves with. When they were looking at an image of a mother with a child on her breasts – the origin of the title Parasite – nearly all of them said it was an image of closeness, tenderness in the film. And that’s not the way it is.

WS: We wanted to show maternity in an ambivalent way.

AS: And for them, certain emotional schemes connected with maternity are unquestionable. A baby stands for goodness, innocence, calm. It’s an instilled image. They wouldn’t admit, even though most of them are mothers, that the experience of maternity is inherently ambivalent. It’s a great challenge: to stir a discussion with images that haven’t yet been digested by the audience.

JM: Such images of maternity are heavily instilled in culture, also visual culture: the Polish mother, Stanisław Wyspiański’s pastel paintings, and so on. Was it one of your inspirations?

WS: Actually not Wyspiański. But when we were preparing to work on the film, we were viewing museum collections and taking photos of the Madonnas. Interestingly, until the Renaissance, babies in the paintings of Madonnas were presented in an unlikable way. I don’t know the reason, maybe it was a matter of the religious context, the necessity to preserve the distance to a saint…

AS: …also from the position of the child in those times.

WS: Later, during our work on the film we made little use of the results of that research, on the film set we already didn’t pay attention to the entire painting iconography of the mother and the child. We paid attention to the way maternity is regarded nowadays.

ŁR: The image of maternity has also changed a little bit recently. The case of “Madzia’s mother” [a famous case of a Polish woman who committed infanticide – transl. note] encouraged people to revisit the figure of the mother in the Polish collective imagination. I guess the case hit the headlines when you were shooting Parasite?

AS: More or less. I don’t know if that story actually unleashed something. “Madzia’s mother” became a figure of the “pathological mother”, which only strengthened the figure of the “holy mother”, whose sacrifice knows no limits.

WS: I get terribly pissed off, and I often talk about it with Anka, that in Poland the questions of maternity are defined by a priest, who is a man, and who doesn’t have a clue about maternity by definition, he does not have children himself…

JM: …some of them do…

WS: …some of them do. But they don’t take care of them. And the situation when the church has so much influence was also something that we talked about a lot when we were working on Parasite.

AS: That’s right, we were even saying that we’re shooting a portrait of a holy family à rebours. We were also referring to the image of the holy family.

WS: Many directors who were not affiliated with the church had also referred to that image before, for example Pier Paolo Passolini in The Gospel According to St. Matthew.

ŁR: It’s just that in your film that rather unholy family does not have any connection with any kind of metaphysics.

AS: For sure there’s no metaphysics in Parasite.

JM: There is no church and church rituals either. A fact that is rather striking because the film is firmly set in Poland, a country that we would instinctively associate with a strong presence of religion in the public space.

AS: Church was there, but we dropped it in the course of editing.

WS: In Mościce there’s a very beautiful church. We shot it from the outside, we never brought any of the characters inside. There was a scene where a character is walking, the camera follows him, it moves off the frame, abandons the character and slides onto an altar in front of the church. Interestingly, the largest figure in the altar is the Holy Mother. She towers above kings and saints. It is a huge statue, and it comes from the 1960s, like the entire altar.

AS: That was too literal.

WS: Just like another scene that we finally decided not to use: Mr Jerzy approaches the mother with a child and together they form a picture that looks exactly like a 15th century portrait of the Holy Family.

AS: We didn’t want to be so straightforward about the relations between them.

JM: At the visual level, the film refers to many images known from Wilhelm’s earlier works. It is opened by a panoramic vista of the chemical plant in Mościce, which you had painted and filmed before. In turn, the images of pregnant women bring to mind the portraits of pregnant Anka from the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw.

WS: I did two exhibitions, one about maternity, the other about fatherhood. Generally, about the visions of parenthood. But the kind of parenthood that is horrible, that drains the human being. There was an image of a hunchbacked man, and so on.

ŁR: It’s interesting how the representation of family changes in your creative practice. Because you, Wilhelm, started from short movies about your love, daily life, happiness. Now, you make Parasite and you show something completely different. You stop talking about yourselves. At least directly because Parasite is also a result of your own experiences.

WS: I was telling Anka about this!

ŁR: Didn’t you feel like making something lighter, something more about yourselves?

AS: A film about a happy couple with two kids?!

WS: There was such an idea, I even wanted to do that.

AS: I’m totally against. We actually used our parenthood experience in Parasite. Sleepless nights, baby’s screaming that you cannot escape, playgrounds I hate.

WS: And besides, Łukasz, I keep making such films. We haven’t abandoned it at all. Right now, I’m finishing one such film for a gallery, a short one, shot on 16 mm. There’s my father and my son, I spent a lot of time recording them on camera. I’m very surprised by the way my father acts in front of the camera: he recognises that I might be right in this respect and he should help me in some way, he surrenders.

AS: And on the other hand, Willi has become a “family painter” in a way. We are less and less part of your films, but we appear more and more often in your paintings.

JM: It Looks Pretty… and Parasite clearly continue the vision of the provinces from your short films.

WS: I’ve recently seen a photo from the 1970s, I can’t remember who made it, it showed a badly ploughed field. There was a field with stripes on it, and some of them were crooked. I’ve always been interested in such Polish lethargy. I was considering going back to Zielona, where we shot It Looks Pretty… and doing something with them once again.

AS: From the short films to Parasite we making a single journey with the camera. And this is a provincial journey, which makes it necessary to domesticate a place, choose a language in order to describe it, but we can always leave.

ŁR: This language of film, the narrative constructs also give you some kind of a buffer between you and the world that you show.

WS: Interestingly enough, even though Anka hails from the field of literature, a field connected with the narrative, and I hail from painting, a field connected with the image, she has a stronger need of abstraction, moving away from a literal narrative than me. I guess I need a framework of the storyline in order to build abstract images around it.

ŁR: It’s obvious, you lack in film what you don’t have in painting.

WS: A bit, I guess, but Anka also has been saying for a few years that she’s tired with the classic narrative.

JM: When we were talking a few years ago in Cracow, you mentioned films that inspired you when you were working on It Looks Pretty… The cinema of Bruno Dumont, but also Polish cinema, for example The Manhunter (Naganiacz) by Ewa and Czesław Petelski. In the case of Parasite it might be harder to pinpoint your sources of inspiration, especially as far as Polish cinema is concerned.

AS: When I think about inspirations for our films, including formal ones and those related to language, what comes to my mind is Herta Müller or the marvellous Romanian-Swiss playwright Aglaja Veteranyj; so poetic prose that displays a rigid formal discipline.

JM: It Looks Pretty… was a film that concerned painful contemporary history. In Parasite, apart from the theme of maternity, there is also a thread related to transformation. At least I see it this way. An elderly man loses his job, he cannot find himself in the new situation, there’s an image of provincial Poland, cinder racing, a second-hand shop. What do you think about such interpretations?

WS: We talked about it after your review of the film. For sure we didn’t have it on our minds from the beginning. For us, Mościce was a natural place. This is what average Poland is like for us.

AS: The things that you’re talking about were very natural for us. We lived in Mościce for six years. This is the way you circulate there. Cinder racing is free entertainment. I myself used to go to that second-hand shop, our mothers too. To be honest, I cannot recall any other second-hand shop in Polish cinema.

JM: In Andrzej Żuławski’s The Shaman (Szamanka).

AS: That’s right, in Żuławski’s film. Anyhow, in Parasite we didn’t want to diagnose things, unlike in It Looks Pretty…, a film with a clear publicistic intention.

WS: This social context makes itself manifest also in different reviews and discussions. This reminds my of a certain biographical context of mine. I was raised with a work ethos, convinced that work is something noble. My grandfather, who is an archetype of Jerzy in a way, would frequently work in a factory without a personal advantage. After his death, he was remembered in Mościce as a person of legendary labouriousness, which was a source of pride for me.

AS: Małgosia Sadowska was right to write that Parasite could be titled Death of a Man of Labour. In Mościce, we have a neighbour who is like Mr Jerzy. He goes out to the shop a number of times to kill time, he tries to fill his days when there’s no work to organise his days any longer.

WS: Because the problem of Mościce is not material poverty. Or at least not only. It’s a different kind of void. People don’t work and social bonds, based above all on the working environment, dissolve completely. I was raised at my grandmother’s who lived right near the nitrogen plant. I’m brimful with her stories about how people were building – literally – the plant in the 1950s. The plant was the centre of social life. Next to where my grandmother lived there was a hall where dance parties were held every Friday and Saturday. Now, it’s a fenced private area.

JM: And because of all the things you’re talking about, for me Parasite is a film about transformation. Or even a broader phenomenon that transformation formed part of: the decline of a form of socialisation that was based on the social tissue that developed around heavy industry. I saw it myself in my hometown, Jaworzno, a town built around two branches of industry: coal mining and coal-based energy production. Jerzy Buzek (Polish Prime Minister between 1997 and 2001 – transl. note) closed down the coal mining industry; for more than a decade, a thicket of bushes took over the place in the centre of the town where the mine used to stand, and now a shopping mall is being built there. The entire social world that developed around the factory is gone.

WS: Yes, this is often forgotten in discussions about unemployment. Unemployment is not only about the lack of income. Work has also an ethical, organisational dimension. It keeps our world from unravelling. I was still able to profit from that world created around the factory. It was a safe world, I could go outside with no problems. I could attend a model making club, extra English lessons. As a teenager, I was very proud that I was living in a self-sufficient part of the city, organised around a factory, where there was a stadium, a community centre and everything else you needed. And if someone wants to leave, there is the Tarnów Mościce station.

Unemployment is not only about the lack of income. Work has also an ethical, organisational dimension. It keeps our world from unravelling.

AS: In our film, losing his job ruins Mr Jerzy to the same extent that his ill-health ruins him. Work gives meaning to his life. The girl doesn’t have a job, she has no one to leave the baby with, she has no chance of getting a job. The fact that she can’t work makes her very lonely.

JM: What is your next project?

AS: It will be an adaptation of three literary texts. The Stranger by Albert Camus, the fairy tale The Shadow by Hans Christian Andersen, and Ukryty w słońcu by Ireneusz Iredyński, which is a brilliantly constructed piece, and to which I’d like to refer above all at the formal level. We have built an initial story. So far we have agreed that the sun will be the protagonist of the film.

ŁR: After the gloomy atmosphere of the first two feature films you had to turn to the light (laughter).

WS: The most inspiring text for me in this project is Andersen’s The Shadow. It is a very well written, very contemporary tale about a man whose shadow begins to live its own life.

JM: A quite frequent motif of a doppelgänger in Romantic prose, from The Nose by Nikolai Gogol to William Wilson by Edgar Allan Poe. It also often appears in film. The Student of Prague with Paul Wegener is a story of a young man who sells his mirror reflection to a mysterious sorcerer. The reflection becomes autonomous and starts to persecute the man.

AS: It is going to be a gloomy film about the sun. “The sun witnessed everything” – the sentence taken from the script of It Looks Pretty… is a good beginning of that new story.

**

Translated by Łukasz Mojsak.

This interview is a fragment from the book by Jakub Majmurek and Łukasz Ronduda (eds.) Polish Cine-Art. Cinematographic Turn in the Contemporary Polish Art. The book maps a new current in Polish cinema: narrative, feature, live-action movies made by visual artists, who cross the floor from the art-world into the movie business. The book consists of numerous interviews with all the actors active in that movement as well as essays analyzing it from a scholarly perspective. The book is available for free here.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)