Veronika Pehe: You run the Office for Social Justice in Warsaw. What exactly do you do?

Piotr Ikonowicz: The Office for Social Justice is an association that gives legal advice and support to people who are endangered by social exclusion, in particular eviction. At the very beginning of the transformation process, a law enabling the eviction of people from their houses and flats onto the street was introduced. This was particularly shocking at the time, as this measure was introduced by a so-called left-wing government. Back then, I was an MP and together with the Polish Socialist Party, we opposed this bill and started to block evictions by, for instance, sitting on the stairs outside the building where a tenant was being evicted. I’m a lawyer by education and we learned how to avoid eviction and social exclusion by legal means without recurring to civil disobedience. These blockades, which are very spectacular, have become only a small part of our activities. The support we give to people who come for help is not only legal advice; we offer inclusion in a group. All of us have some skills and spare time that we dedicate to help one another, whether this means teaching people maths or repairing their drains.

Why is the housing issue so central to your activities?

It is the most significant means of preventing social exclusion – having a place to keep your things. That’s how you recognize a homeless person – they have all they own with them. Housing is also key to keeping young people at home, because if they leave, who is going to build this country?

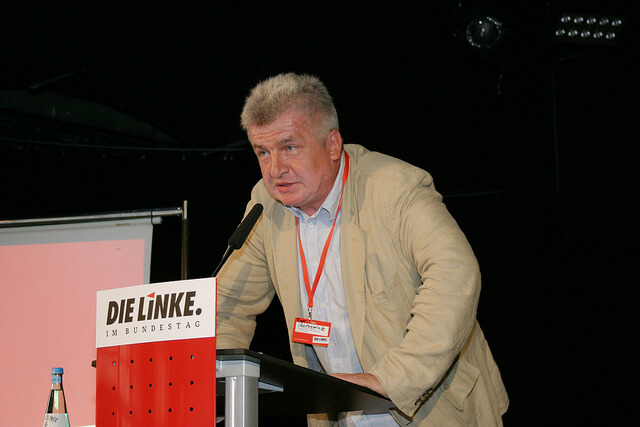

Piotr Ikonowicz

is a Polish politician and journalist. He was one of the founders of the Polish Socialist Party and in the 1990s a Member of Parliament. Today, he is head of the Movement for Social Justice (RSS) and runs the Office for Social Justice in Warsaw, which helps people in difficult housing situations.We try to make life easier for excluded people. We prepared a general draft of a new tenants’ law, which was not approved by the previous parliament. Apparently there was not enough time and political will to do it, but it did give an incentive to local governments to build social housing subsidized by the central budget. And this idea has partly been adopted by the new government. They are even directly using excerpts from our draft.

The current government declares itself as right-wing, yet it has launched this social housing programme. Will it succeed in helping people?

It’s not so simple. First of all, the government will have to break the resistance of the developers’ and banking lobbies, which are very powerful in Poland. The new social housing programme is based on the idea that people can economize, that they can put some money aside for their housing purposes. This is just not the case. About 80% of Polish households have no savings at all, and those who have any have very little to put away. The government is relying on people saving up – once they do, they will receive a bit of help to rent social apartments. If this doesn’t happen, another one million young people will emigrate. At present, it is immensely difficult for young people to have a fresh start, create a family, marry, and have children, because Polish apartments are overpopulated.

Why is the housing situation in such a poor state?

Because during the transformation process, all authorities were convinced that the only viable way to get a flat was to get a commercial mortgage. But this aspiration was only addressed to a small section of society. The middle class in Poland is a tiny minority! Yet all the parties are praying to this middle class. The necessities of the rest can only be fulfilled by regulated rents, because half of the tenants of community flats are in debt.

So what would a good social housing policy look like in your opinion?

If we want to keep young people at home, we have to offer public housing with low regulated rent. Their first salary is low and so the rent needs to be low too. If not, they will go abroad where such policies exist.

If you ask somebody in Poland whether he or she is poor, they reply that no, they are not a bum, not a drunkard, they are not lazy. The image of the poor person is of someone who is lazy – a sinner.

Does this mean social housing should be aimed mainly at the young? And is it also predominantly young people who are seeking help in your Office?

Not so many, but there are some. These are young people who have taken out a mortgage and have ended up going bankrupt. If you have contracted debt on your mortgage, you can just be evicted onto the street. In this way, people who lived in the false consciousness that they are middle class become the underclass, they become homeless. We are trying to combat this by cooperating with local governments and through media coverage. We are often successful, as this in an interesting topic for the media. They have finally started to talk about poverty, a subject they were avoiding for decades.

Why this change? Why is poverty no longer a taboo subject?

For a quarter of a century, we were fed an official narrative of optimism: there’s no poverty, everything is ok and and people like me are just crazy people supporting bums who refuse to work. This narrative was so embedded that even people on the post-communist left would often tell me: “It’s very kind of you to take care of this tiny minority of poor people in our country”.

The current Law and Justice (PiS) government realized this is not the case and now it’s official: a huge part of Polish society is simply poor. If the majority cannot afford to put money aside, if they cannot afford to go on holiday for one week per year, that means they are poor.

You say that PiS has picked up on these problems, but are they also finding solutions to them?

They noticed the condition that society is in. If you ask somebody in Poland whether he or she is poor, they reply that no, they are not a bum, not a drunkard, they are not lazy. The image of the poor person is of someone who is lazy – a sinner, whose main sin is that they have no money and cannot pay their bills. Whenever somebody comes to us who is about to be evicted, they always have a tendency to justify themselves – that they are not a bum, that they are hardworking, but have simply found themselves in a difficult financial situation. I don’t need to have this explained to me. This stigma is now slowly being overcome, but I think the present government is still a prisoner of this vision. They notice some things, but not all. Poverty in Poland has the face of a child – we spend relatively little money on children, even compared to places like Romania.

So we need to change the perception of poverty in society?

Yes. Nowadays, there is a lot of talk of the rise of neo-fascists and nationalists– and it’s all real. But until now we had another kind of social discrimination – despising people because they are poor. People were offended, humiliated by this. And humiliation is the source of all kinds of prejudices. Fascism arose from the humiliation of the German people after the end of the First World War. Humiliation is dangerous and produces a lot of moral suffering for those who are taught that they are the worst kind of people.

With the current refugee situation in Europe, you have to realize that it is partially understandable that people in Poland might have prejudices against refugees in Germany who receive 1000 Euro a month – they would never have dreamt of such money! There’s no social system, no real benefits in this country. Whenever somebody comes to me to say they’re unemployed I say ok, but where do you work? They have to have some kind of job, otherwise they wouldn’t make it.

How many people are you able to help and do you cooperate with other organizations?

We have groups all around Poland. Our method is based on social inclusion, the group becomes a community. We give people a chance to not just give or receive help, but to become conscious political citizens. It’s a big step from being a victim of the system to becoming a militant against the system – this gives people a sense in life.

We have to realize that the welfare state was a coincidence in the history of capitalism. It won’t repeat. We have to look for some solutions that go beyond capitalism in the present phase.

We cooperate with tenants’ movements and urban movements. For instance, we are now opposing the proposal of building about twenty skyscrapers around the Palace of Culture. We also work with anarchists and squatters, who are very close to each other. But if you have to decide between the interests of the affected people and your dearest political convictions, the interests of the people should always prevail. Some groups want to make a lot of noise through dramatic actions and further their political programme, while we are inside the local council building, negotiating. This is what makes us efficient in actually helping people.

What about working with more established political parties? Is there any will from their side?

We have to realize that the welfare state was a coincidence in the history of capitalism. It won’t repeat. We have to look for some solutions that go beyond capitalism in the present phase. This requires imagination and boldness. The main current of politics is not the way forward.

How are we to find alternatives if the narrative of contempt for the poor you have described is so ingrained?

This is a question of how to change people’s minds and open them up to the world. And to convince them that a profound social transformation is possible. I don’t even use the word revolution, it scares people. This transformation should be based on real economic proposals. If the WTO can impose draconian measures, we can also imagine the opposite. International corporations need to be submitted under democratic control. Corporations are very efficient, we can use them for humanity, not against it. It’s all imaginable and it’s all very practical, but it requires one condition: the majority has to win the elections. We definitely need to create a global social economic perspective, because if the majority wins elections, the result can be something else than some form of socialism. Socialism means that society is run by the majority, you socialise the system and in this way you empower the people. The more you socialise the structure of power, the more the inequality of wealth becomes unsustainable. For this, we need to think beyond one state, even if the only way of changing something here and now is to change something at the national level. The response to neoliberal globalization is to empower the people and we cannot leave this to nationalists.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)