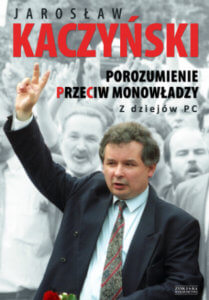

The autobiography of the Polish “Leader of the State,” as Kaczyński was called during his famous meeting with Viktor Orban in June 2016, makes fascinating reading. Not only because the author is undoubtedly a brilliant storyteller, but also because of what he thinks matters most for Polish politics. Of course, Jarosław Kaczyński creates his own personal mythology in the book, but perhaps the most interesting parts are the moments where he (subconsciously?) deconstructs the official line of his own party. He greatly exaggerates his historical role and sometimes falls into a tangle of inconsistencies and at the same time, his autobiography often says or suggests things which are embarrassing for his own party and his supporters.

Not only because the author is undoubtedly a brilliant storyteller, but also because of what he thinks matters most for Polish politics. Of course, Jarosław Kaczyński creates his own personal mythology in the book, but perhaps the most interesting parts are the moments where he (subconsciously?) deconstructs the official line of his own party. He greatly exaggerates his historical role and sometimes falls into a tangle of inconsistencies and at the same time, his autobiography often says or suggests things which are embarrassing for his own party and his supporters.

Exaggerated truths

Let us start at the very beginning, or rather at the start of his career in the opposition.

1.

Jarosław Kaczyński actually did collaborate with the democratic opposition for a few years before the rise of the Solidarity movement: he started cooperating with the Workers Defense Committee after being recommended to its leaders by Jan Józef Lipski, the then non-communist left-wing guru in Poland. He had been detained by the police a few times and had refused to sign a “declaration of loyalty” to the people’s government following the imposition of martial law in 1981.

FACT: Contrary to what he is trying to suggest in his book, he was not an activist in the first circle of the Solidarity movement. In fact, there was a prominent Kaczyński in the movement – but it wasn’t Jarosław – it was his twin brother Lech.

2.

Jarosław Kaczyński suggests that he was an ‘expert’ of the largest region within the Solidarity movement.

FACT: The team responsible for this region comprised of five people who were officially nominated by the Regional Board in ‘Mazowsze’ (Jacek Kuroń and Adam Michnik together with legal experts Jan Olszewski, Wiesław Chrzanowski, Andrzej Grabiński). In turn, his brother Lech was a member of the Committee of Experts, set up following the August agreements of the Inter Founding Committee (which prepared the registration of Solidarity).

3.

Kaczyński writes about his talks on behalf of Solidarity with the then Prime Minister, Mieczysław Jagielski.

FACT: As the most important historian of the period commented: “At most Kaczyński was permitted to hand important letters in their envelopes to Mr. Jagielski, because he was not invited to attend any talks”.

4.

Jarosław Kaczyński recalls his active participation in the meetings of the Provisional Coordinating Commission – the elite underground leadership of Solidarity.

FACT: He was not a member of the body (instead his brother was). These were clandestine meetings in which outside people were not allowed to participate; Professor Andrzej Friszke acknowledges however, that “on occasion the secretiveness was relaxed […] as such Lech could have almost definitely taken Jarosław to sit in with them”.

5.

In the second part of the 80s, Jarosław Kaczyński became a member of the secretariat of the National Executive Committee – the new management structure of Solidarity and of course, he writes extensively about this. In his version, the secretariat rises to the rank of the conceptual “brain” of Solidarity.

FACT: Kaczyński did not spend any time serving in a leadership or consulting role; he only performed technical and administrative tasks.

Kaczyński is simply lost in his testimony

In every important event, it is easy to identify his inconsistencies or outright contradictions between what he says he did and what he actually did.

6.

Almost from the beginning of his story, Kaczyński places himself in opposition to the intellectual elite of left-wing provenance, accusing them of alienating Polish society (as some members of Solidarity and KOR had communist origins) amongst other things.

FACT: He repeatedly emphasizes his own distaste for the everyday behavior of the real “ordinary people”: after almost four decades, he criticizes their vulgar vocabulary and the lower intellectual level of his working colleagues from the pre-August opposition.

7.

Kaczynski dishonestly presents himself as a victim of the Polish justice apparatus after the democratic transformation of 1989. When asked to present evidence of political repression against him, Kaczynski refers to the time when he was sued by Mieczysław Wachowski, a high-ranking official under president Wałęsa’s administration, for libel.

FACT: Kaczyński publicly accused Wachowski of having been a secret communist police agent. He based his accusations on highly dubious material, namely a blurred photo of five young men playing soccer at a summer camp for secret police officers, one of whom he claimed was Wachowski. That photo, he later explained, was given to him by unknown men in strange circumstances. A few days after Kaczyński’s accusation went public, a man named Arnold Superczynski, a former police chief of Lublin, went to the press to admit that he recognized himself in the picture as the man Kaczyński claimed to be Wachowski.

A man of many contradictions

Kaczyński sometimes says things that his admirers and followers find surprising or simply uncomfortable. At times, the surprise also comes from what he does not say.

8.

From the first pages of his autobiography, Jarosław Kaczyńsk emphasizes the separateness (or “intellectual alienation”) of him and his brother from the left-wing opposition circles who hailed from communist origins, revolving around the figure of Jacek Kuroń.

FACT: His own description of the events from the 70s and early 80s (and which is confirmed in other documents) indicates that for several years, Jarosław Kaczyński worked closely with Kuroń and his circle, who at times even served as a mentor to him.

9.

PiS historians and journalists repeatedly portray Lech Wałęsa, from the beginning to the end, as either a collaborator or an unwilling puppet of the communist secret services and their followers after 1989.

FACT: Jarosław Kaczyński explicitly endorsed Lech Wałęsa’s leadership skills (particularly during the wave of strikes in 1988) and recalled examples of close collaboration between his brother Lech and the leader of the Solidarity movement; he implicitly admits that Wałęsa was the catalyst for both twins to become engaged in mainstream Polish politics.

10.

Kaczyński criticizes Jacek Kuroń for his disrespectful attitude towards the problem of spies within Solidarity.

FACT: The (almost empty) contents of Kaczyński’s personal file in the secret service archives with regard to his long-standing opposition activities undoubtedly illustrates the weak level of infiltration of Solidarity by the secret services. The secret polices’ knowledge of Kaczyński and his circles was in fact minimal, and there were almost no agents in his immediate surroundings – evidence which refutes the claims of the party and Kaczyński’s supporters about the omnipresent and omnipotent infiltration by the security service.

11.

Numerous right-wing commentators and historians who are close to Kaczyński, treat the Round Table talks as a sign of betrayal by the nation’s elite opposition.

FACT: Jarosław Kaczyński describes his own and his brother’s work in the preparation of the Round Table talks, whilst omitting one detail – namely his signing (along with Adam Michnik, Tadeusz Mazowiecki and Andrzej Stelmachowski)of the so-called “Declaration for the need for dialogue” in August 1988, which paved the way for negotiations of the opposition groups with the ruling camp. The presence of the Kaczyński brothers within the mainstream Solidarity movement, along with subsequent political opponents, as well as their commitment to the talks with the communist government cannot be disputed. Interestingly, during the talks of one of the so-called under-the-table committees about the rule of law, Jarosław Kaczyński sat together with Professor Adam Strzembosz, who is now a sharp critic of PiS’ policy towards the Constitutional Court and the entire justice system. As is indicated by Professor Friszke, Kaczyński’s views on the “autonomy and independence of the judiciary and the absolute independence of judges did not differ then to those of Professor Strzembosz”.

12.

Kaczyński describes a secret meeting with Adam Michnik, the editor-in-chief of “Gazeta Wyborcza” in 1993, during the campaign against the then-president Lech Wałęsa.

FACT: Whilst the interlocutors did not get along even then, most of Kaczyński’s supporters find it shocking that he met with his “archenemy” and discussed the idea of a potential collaboration with the very man whom he distances himself from on almost every page of his book.

13.

Kaczyński’s comprehensive political autobiography does not address the story behind the so-called FOZZ (Fund for Servicing the Foreign Debt) affair – probably the most infamous economic scandal during the period of transition, which for right-wing commentators in Poland is the very essence of post-communist pathology.

FACT: As historian Antoni Dudek explains, the subject is uncomfortable for Kaczyński due to the fact that the money from the affair was mainly used in the early 90s to informally finance all of the major political parties in Poland. At that time, Kaczyński’s party, “Center Alliance” (PC), was struggling with serious financial problems and as Kaczyński vividly describes, was surrounded by strange businessmen offering suitcases of money for various suspicious political and economic “favours”. In turn, in relation to another scandal from that era associated with the media company “Telegraf”, Kaczyński justified his position in a far from convincing manner: that his signature which was found on the founding constitution of the controversial company was a forgery; in fact, this crime was never reported to the prosecutor’s office. The story of “Telegraf”, which in spite of its relation to Kaczyński, who disconnected its ties to PC and also himself, was explained by Dudek as “a typical attempt by contemporary Polish politics to exit the vicious circle of a lack of resources and an insufficient presence in the media”.

**

Translated by Louisa Naks.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)