Sitting in the narrow Warsaw apartment that doubles as an LGBT advocacy group’s headquarters, Stanisław Orszulak doesn’t feel confident about Poland — or even safe. As a trans non-binary Pole, they are distressed by the increasingly hostile government rhetoric directed at members of the country’s LGBT community.

“In our current climate, people don’t want the government to know that we are trans,” says Orszulak in crisp, perfect English. “We want to be safe.”

I’m scared for my loved ones because … I don’t know what’s going to happen with them.

Abandoned by Poland’s major political parties, marginalized by the legal system, and attacked by the current government, Polish LGBT voters are apprehensive of October’s parliamentary elections. And while pessimistic about the election’s potential outcome, the community remains buoyed by a drastic upsurge in LGBT activism.

A large, visible minority in a largely homogenous country, Poland’s LGBT community has been progressively vilified by the ruling Law and Justice party (known by its Polish acronym: PiS) as the 2019 parliamentary elections have drawn closer. In this, many see a cynical attempt by the government to mobilize its conservative base.

“I do believe that we are just a tool in their political game,” says Mirosława Makuchowska, the political director for Kampania Przeciw Homofobii (The Campaign Against Homophobia) — one of the largest gay-rights organizations in Poland — and a vocal advocate for LGBT rights. “Unfortunately it just shows that Polish society is still very homophobic and we haven’t made the lesson that the rest of Europe has … I believe that the Law and Justice’s strategy was to pick the most controversial issue and the most effective to trigger fear.”

Others fear that the government’s willingness to sacrifice minority rights at the altar of electoral victory represents a sharp turn away from democracy in Poland and believe that the country — a large EU and NATO member — could follow the illiberal models laid out by Viktor Orban’s Hungary or Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

“I’m afraid that the vast majority of [Law and Justice politicians] are just utterly cynical and they’re willing for the sake of retaining power and support to risk other people’s safety, well being, and dignity by using language like this,” says Marek Szolc, the only openly gay member of Warsaw’s city council. “This strategy apparently is working quite well in Poland and Hungary, and in Russia and in other states.”

Some have pointed to the similarities between the rhetoric used by the Law and Justice party and that used in Russia’s “anti-LGBT propaganda” legislation as reasons for their distress.

“I’m scared that it’s going to go even further,” says Julia Kata, the vice-president and advocacy officer for the trans advocacy organization the Trans-Fuzja Foundation. “They already started to [persecute] LGBT organizations, so I’m scared they’re gonna try to put the laws like in Russia, like the propaganda laws.”

Hope

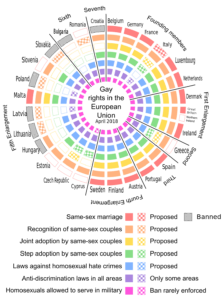

While the most recent round of political attacks against them has been exceptionally vitriolic, Poland’s LGBT community has always faced discrimination. In terms of enumerated rights and protections for Queer people, Poland ranks last — tied with Latvia — among the 28 EU member states. Poland does not recognize same-sex marriage, grant civil partnerships, or have LGBT hate-crime legislation; a 1997 amendment to the constitution defines marriage as between a man and woman (though there is some legal dispute over its exact wording) and while cohabitating same-sex couples do have limited shared legal rights, adoption of children by a non-biological same-sex parent is not allowed.

Since the transition to democracy in the 1990s, even centrist political parties have been hesitant to deal with LGBT issues for fear of alienating conservative social actors — most notably the Catholic Church.

“They say we’re going to do [civic partnerships and other LGBT issues]. We can deal with that after the election,” Makuchowska says. “This is exactly what they’ve been doing for like 10 years.”

Yet despite these hurdles, LGBT activists have managed to achieve certain victories in the public sphere. Public opinion of homosexuality has seen a steady positive — if only relatively — change and in 2011 Poland elected Anna Grodzka — an openly trans woman — to parliament.

Without the support of Poland’s political parties, non-governmental organizations like Kampania Przeciw Homofobii (the Campaign against Homophobia) have mobilized the LGBT community through corporate “Rainbow Networks” — support groups made up of coworkers that aim to make companies safer for Queer employees — and events like Warsaw’s March for Equality.

Yet a deepening resentment towards the LGBT community has spread across the country and PiS has spearheaded a conservative backlash.

Backlash

Against the backdrop of a worsening European migration crisis, the conservative Law and Justice party won a majority in both houses of parliament in 2015 as well as that year’s presidential contest. In both elections, PiS focused heavily on demonizing refugees as a threat to traditional Polish society despite no large refugee community existing in the country.

In the years following its electoral victories, Law and Justice has tamped down slightly on its anti-refugee rhetoric while silently accepting close to two million Ukrainians fleeing war with Russia and a faltering economy. It is this strategy — fomenting fear to win elections and then backing off — that many of PiS’s critics denounce as cynical political demagoguery.

Magda Dropek is the former editor for Queer.pl, a Polish LGBT news site, and a current opposition candidate for the Lewica (Leftist) coalition. In her opinion, PiS is simply replicating its earlier strategy, but with LGBT people as the new “other.”

“So four years ago, Law and Justice built their campaign before the general elections on the fear to refugees because there was a refugee crisis in Europe,” she says. “So this year, they put their attention on LGBT community as those ‘others’ — something different, something which in their opinion, doesn’t fit to some traditional Christian society as they call Polish people.”

In February, Warsaw Mayor Rafał Trzaskowski signed a 12-point declaration that — among other things —established an LGBT youth shelter and access to sex education in public schools. Law and Justice seized on these policies as evidence of — what they call — an invasive, foreign LGBT ideology which would sexualize children and threaten the Polish family.

Szolc was involved in getting the declaration signed and for him, PiS’s critiques are just an attempt to repackage homophobia.

“It’s considered fascist when you say, we want our country to be free from LGBT people,” he explains. “It’s much safer to say … that we are against some sort of ideology. We are protecting family values or we are trying to, as they said in Poland, protect our children against being sexualized, whatever that could mean. It’s the same message but in a — let’s say — a slightly more acceptable package.”

Fear

While PiS has never been friendly to the LGBT community, it has been particularly eager to focus its base on this issue now in what some describe as an attempt to divert attention from a series of scandals that have rocked their ally, the Polish Catholic Church. In 2018, Kler (The Clergy) — a film that focused on controversial behavior inside the Polish Church — broke box-office records and triggered hundreds of sexual assault victims to come forward with accusations against church officials.

“I would say [for about] one year now or maybe a little bit more, there [have been] an amazing amount of pedophilia scandals in the Catholic Church,” says Kata. “So [the Church and PiS] had to find something against that, so to cover up all those things so they came up with the LGBT threat, I think. And they’re using it a lot.”

Instead of criticizing the Church, PiS has tried to frame the debate around sexual minorities with some supporters saying that homosexuality was to blame for priests assaulting children while other far-right politicians have argued that policies aimed at helping LGBT groups would promote pedophilia.

For those already predisposed to agree with PiS’s policies, these claims aren’t hard to believe. Linking homosexuality and pedophilia has long been a staple of Polish homophobia (a common Polish slur for LGBT people loosely translates to pedophile).

“I’m quite active, for example, on Twitter,” says Dropek. “It’s like that I don’t have a day without hate speech. Very hateful messages, private messages to me calling me, you know: pervert, deviant, pedophile or wishing me death for example.”

Due to a lack of hate-crime statistics, it is hard to know how much PiS’s language has contributed to violence against LGBT people, but it inarguably has. In the PiS stronghold of Białystok in eastern Poland, thousands of people protested against the city’s first-ever pride march. Outnumbering marchers four to one, counterprotesters threw rocks and bottles while some residents were reported to have dropped bags of flour from their apartments as the march wound its way through the city.

While many were shocked by the violence, a local Catholic parish thanked the counter-protestors for, “joining in defense of Christian values” and for defending “our city, especially children and youth from the planned immorality and depravity.”

These statements echoed those made earlier by PiS chairman — and de facto leader of the country — Jarosław Kaczyński who said that LGBT activism represents an “attack conducted in the worst possible way, because it’s essentially an attack on children.”

These — and many other — acts of homophobic violence have mobilized the LGBT community and their allies at a level not seen before in Poland. On Twitter, thousands have responded to the attacks in Białystok by either coming out themselves or showing their support for the Queer community through the #JestemLGBT (I am LGBT) online campaign. And on the ground, there has been a flurry of equality marches across the country — including several first-time marches.

“I think that Law and Justice being in power has triggered and mobilized LGBT communities in Poland very much,” Makuchowska says. “There is like tons of activities and solidarity actions. And, this year we had like [26] I think equality marches, LGBT equality marches, and … four years ago it was just seven. So it’s a dramatic increase that shows the actual need for mobilization and standing against this.”

Yet for all these acts of defiance, fear still permeates the community as they ready themselves to go to the polls in October.

“I’m scared for my loved ones because — I have LGBT people in my family — I don’t know what’s going to happen with them,” Kata says. “Poland is under … a serious threat for democracy.”

Szolc agrees and fears that this is a make-or-break election for Poland.

“If [the opposition doesn’t win] then the situation will not improve … We’ll be, we’ll be lost,” Szolc says. “I’m afraid many people will give up — I mean I already have many friends who have decided to go elsewhere. My biggest fear is that during the 2023 elections [the next elections], there’s simply might be too few people to fight.”

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)