On November 1st, the short-hold lease on three council housing blocks in Bánovce nad Bebravou, predominantly inhabited by Roma people, expired. The city council decided not to extend the contract which had, previously, been renewed several times without issue. Instead, the inhabitants were asked to vacate the premises until December 1st.

In response to on-going problems with the state of these buildings Michal Schlesinger, a representative of the council, has offered a ‘solution’ that has resulted in the eviction of 400 people onto the street in winter, during the advent season. ‘One solution is for these tenants to find new accommodation, or to stay, temporarily, with relatives, after which they can start afresh.’ It is, however, unrealistic to expect approximately 400 people, including families with small children, the elderly, invalids, or otherwise disadvantaged tenants, to find alternative accommodation for just a month in a town the size of Bánovce nad Bebravou (population: 18,000).

Thus the question remains, why has this decision been taken now?

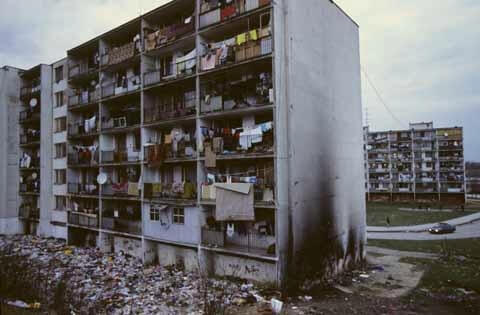

Due to the dilapidated state of the council housing estate, in 2010, the town of Bánovce suggested inviting bids for investment in its reconstruction. The council, as the proprietor, however, has failed to fulfil its duty to provide tenants with alternative accommodation during the period of the reconstruction of these buildings. In fact, this planned reconstruction exists only on paper and has, since then, been seemingly forgotten. Upon visiting the building, it has become clear that no substantial reconstruction has taken place since 2010. Nevertheless, this has not prevented this reconstruction from disrupting the buildings’ function. This disruption is the basis upon which the tenants have been asked to vacate the blocks of flats. This situation was still unresolved at the end of November. The tenants could remain in their flats, at their own risk, without water, gas or electricity. From December 1st, however, the tenants would be living illegally on the premises, with further, severe limitations of utilities. The head of the city administration office, Alexandra Gieciová, revealed that the council is ready to turn their threat of eviction into action: ‘It is our duty and our desire to protect the lives and health of the people living there. This also means that, should they refuse to vacate the premises voluntarily, we will, of course, take legal action.’

Once again, the political party most active in this affair is the local branch of the Kotleba’s far-right party, ĽS NS.

Springing up out of nowhere, ĽS NS local representative and businessman, Anton Grňo, became involved in the situation. Grňo regularly riles up local inhabitants, not only setting them against the aforementioned tenants, but also against local authorities, claiming that the city’s intention is to secretly build a new blocks of flats, despite its refutation of such claims.

It is clear, upon visiting K nemocnici Street and these blocks of flats, that this is a particularly tense situation. Proti Prúdu, an NGO focusing on the problem of homelessness in Slovakia, and Michal Zálešák, a lawyer from the European Centre, have pointed to the fact that the council’s decision violates the UN’s International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. They claim that the city is responsible for the welfare of their most vulnerable inhabitants, as well as for maintaining the state of property in the city’s possession.

Another marginalized site, Luník IX, in Košice, home, once again, to a largely Roma community, is likely to experience similar problems. Two blocks of flats are to be torn down and the city has called for the immediate vacation of the premises. Six blocks of council housing have already been torn down in this area, resulting in the inhabitants ending up in the nearby settlement.

In such cases, it is clear that the improper administration of cities creates a vulnerable population, resulting in homelessness and the rise of informal settlements. It is shameful that there is no law in Slovakia that would force local authorities to provide alternative accommodation, and protect tenants from eviction in winter. However, the underlying issue is that accommodation is unaffordable and this problem is compounded by the absence of a social housing act which protects a fundamental right to housing.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)