The happy housewife is a fantasy figure that erases the signs of labor under the sign of happiness. – Sara Ahmed,

“The Promise of Happiness.”

Labor is one of the most unnoticed aspects of our lives, despite being responsible for everything around us, the reason being that the result of labor eclipses the process of labor. The materiality of an object makes it something in and of itself, not something made by a person in a complex system of social relationships.

It’s even worse when the labor doesn’t produce something tangible. Take, for example, the work done by a young mother – cooking, feeding the children, washing dishes, cleaning up. The result of her labor is that there are clean dishes in the same place they were before. This increases the temptation to believe in the fantasy that things such as a clean home, healthy children, emotional and psychological well-being of family members exist on their own, not as the result of the everyday work done by a woman to maintain the status quo.

Labor goes even more unnoticed when it comes to non-material things – personal growth or decency, for example. Being a decent person means every day having to counter indecent people who pressure you, doing good deeds, making decisions.

Giving attention to labor and being able to reconstruct the process shifts the focus of our assessment of reality, and I believe this shift is extremely important for analyzing social processes, and understanding human personality, it’s formation and development. A person’s identity (self-awareness, self-image) consists of two components. A person identifies with certain models (social norms). These models are general and taken for granted. Identification with them is an individual process, it is labor. These processes and various aspects of them can be traced in the project, “TEXTUS. Embroidery, Textile, Feminism.”

What kind of labor and identity does embroidery speak to us about? Its surface blends with nationalism, as with how ethnic clothing is a matter of pride, an element pointing to the uniqueness of a nation. But its beauty eclipses the practices of culture: we know very little about the women who made and wore embroidered blouses. We don’t think about at what age they wore their beautiful wedding costumes, conditions of childbirth, or how many hours went into making a shirt from home-grown, harvested, spun, woven, bleached, sewn and embroidered linen. We don’t know what other talents they could have mastered were they not mired in housework and motherhood. It was something they couldn’t have even dreamed of, because they didn’t know it was possible for women. But we can find out. These tiny lace stitches bear witness to the times, to labor and social structures of the past.

Modernity is more difficult. Everyday objects don’t have a romantic patina that would force us to peer into someone’s life or the kind of jeans they wear (pop icons and Instagram stars not included). This is the misfortune of modernity: the plurality of actions creates the present and lays the ground for the future receiving the least attention and analysis. We replace it with patterns and stereotypes, because it is very difficult to take apart a process in which you are involved, which is part of you, and to critically assess its components.

Herein lies the value of contemporary art. It is immediate, sensory, intelligent. You can get immersed in it, encounter it, close yourself up in it – and each time something unexpected will happen. This is especially because critical artists often choose themes that are normally hidden, those complex systems of social relationships that produce things, that exist now, alongside us, within us.

In TEXTUS the feminist optic and mediums selected (textile and embroidery) point to a set of themes with which viewers and authors interact: labor, norms and identity. All these themes flow organically from the materials and the techniques used; all are interrelated.

The process of embroidery is very much like that of forming identity, especially the kind most popular in our culture – cross stitch using ready patterns. As noted earlier, the truth behind identity is that it is always a recreation of a model, a “norm” (woman, heterosexual, Ukrainian, lawyer, etc.). But this replication is not passive, it is active and individual every time. The same with embroidery made using a design pattern – it always has its own features introduced by the embroiderer: the shade of the threads, the nature of the stitches, the knots on the reverse side. There are lots of small personal decisions, and the devil is in the details.

Embroidery patterns are a good metaphor for social norms and their ethical ambiguity. Accepted social patterns (behavior, identity, values) both suppress and rescue us. They suppress us if they are too strict and don’t allow personal experimentation, don’t update fast enough. They rescue us by offering guidance in the endless sea of existence

Many of the works in the exhibitions are about repressive norms. Which isn’t surprising because in a patriarchal culture female identity is restricted by a very narrow set of available identities, all of them traditionally centered around motherhood and sexuality – a source of male pleasure. Women feel the need to protest and reject those restrictive models and create new ones, with many more available, socially acceptable and meaningful options.

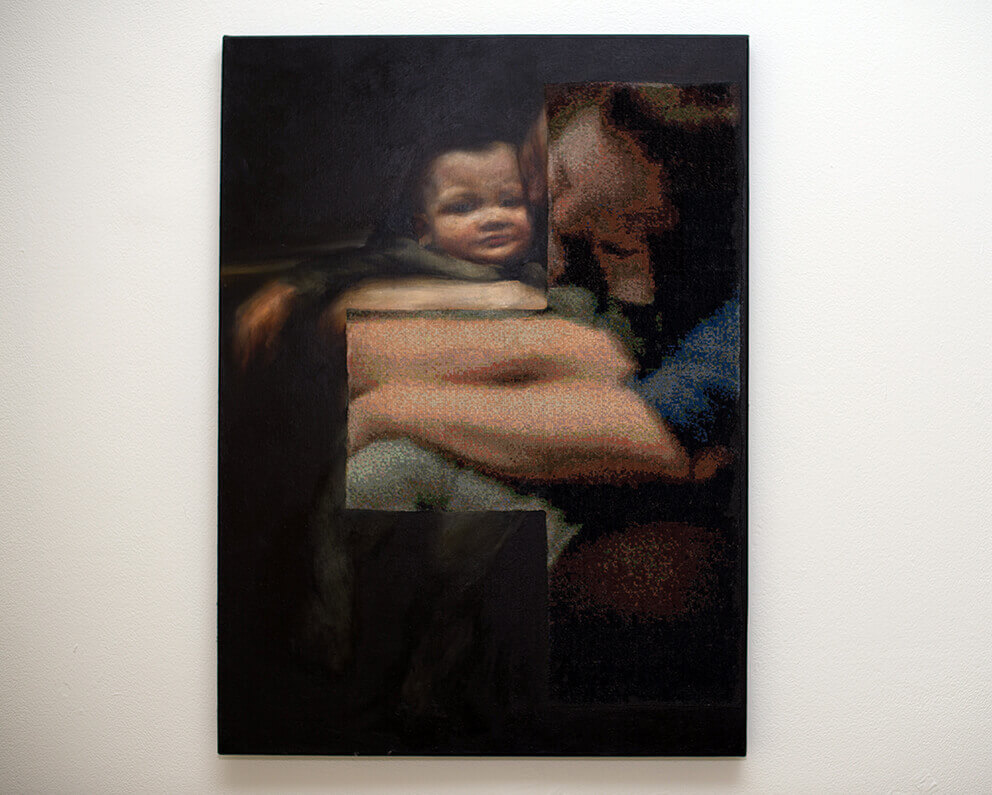

But not everything is all right even with traditional identities, and Anna Zviagintseva notes this boldly. The artist develops a fine intellectual analogy between the experience of motherhood – seemingly typical, but every time unique – and pen marks you see on papers by the cash register in stationery stores, which too are the same yet different all at once.

It is radical to compare motherhood with something so unnoticeable, banal, unimportant, and at the same time bring this “unimportance” into the prestigious and symbolic space of art. Zviagintseva, who calls “Single Entries” a “monument to unique routine actions,” pushes the viewers to see the uniqueness behind the sentimental and pretentious things said (mostly by men) about motherhood. As an everyday job, motherhood involves “actions that are difficult to describe, not least because the woman performing them doesn’t have time to describe them.” Olesia Trofymenko also speaks about this in her work “Iconic.” The artist’s image of mother and child using mixed techniques – half painting, half embroidery – emphasizes that motherhood is not a vision (as it was for centuries in a culture created by men, with all its Madonnas and Virgin Marys). Motherhood is a process of labor, and no image of a woman holding a child on her lap can convey all its difficulties and paradoxes.

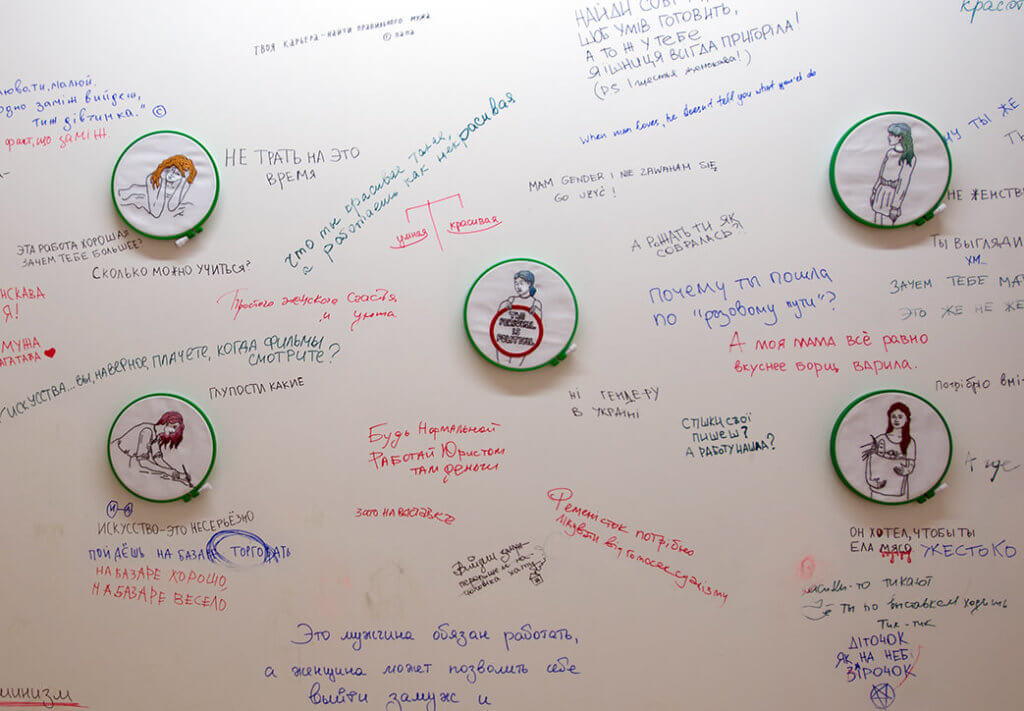

This “person-creating labor” can involve working on oneself to fit into normative patterns or to go beyond them. Artists such as Tetiana Korneeva and Anna Shcherbyna speak about norms outwardly and negatively. Others look for subtleties. Oksana Briukhovetska’s installation, “Whips,” which uses children’s tights to make what looks like long braids, speaks about the time in a girl’s life when social norms begin to have a stronger influence on the formation of her body and personality. Alina Kleitman’s installation is a tunnel into the subconscious of an adult woman, where discriminatory demands to provide pleasure for someone else are engrained.

There is another kind of labor, the kind from which we “earn a living” (this phrase implies that earning and living are two separate existences). Sometimes you spend so much time earning that there’s nothing left for living. The Shvemy sewing cooperative embodies this notion in a performance that recreates a 12-hour shift at a garment factory. Sometimes a job becomes a prism through which a social group is perceived, it forms a ghetto of identity. Prague-based artist Sofia Vremennaya points to how “Ukrainian women cleaning services” has become a standard phrase in Poland and Czechia.

Often these routines – norms absorbed since childhood – and external circumstances clutter our horizon so much, weigh us down and weaken us, that it seems the only way to go beyond them is to not exist at all. As artist Valentyna Petrova joked on Facebook: “This life is too expensive and way over my head.” In her embroidered “Self-Portrait” she applies this principle, leaving behind only the story of the work, instead of the work itself. The author’s intention is to show not her face, but the realities of an impressionable (precarious) young professional living in a big city. Petrova created her work in the valuable moments after her “main” job, and in the same way gradually destroyed it over the course of the exhibition.

The act is not a symbolic suicide. The artist has consistently avoided creating tangible objects that can be sold. She positions her creativity as an event, an intangible but important interaction. The point of this gesture is to try to imagine and bring closer a different world in which art and creativity mean something different than what we are used to.

Reflecting on the intangible in unknown territory, Petrova uses a very traditional method – embroidery on canvas. Her work demonstrates what philosopher Luce Irigaray called “deflection” in the process of (re)creating oneself, and in which she saw a realistic way of creating something truly new. Revolutionary fantasies about building the world from scratch in reality stumble upon existing aspects of identity that won’t just disappear in a split second. Everyone who goes down a road of personal development, feminist or otherwise, knows the strong internal barriers they will face at times and how much energy it takes to overcome them. Not to mention an external social background that is even more resistant to change.

Stressing the importance of deflection, not a complete break, Irigaray suggests taking small steps instead of huge leaps. If you recreate a norm, only somewhat differently, mix up accents, bring in new meanings, in the long-run the multitude of small and subtle changes create a fundamental transformation; it changes the norm as such and blurs its boundaries. We often don’t appreciate these small shifts, trying instead to measure up to a radical ideal instead of the difference between the past and present state of affairs.

In her work, Petrova took the beaten track. She embroidered a self-portrait – textured, colorful, eco-friendly (she deliberately used recycled materials) – until she decided to deviate from the process of creating a work of art. The seemingly insignificant (and unnoticeable to the exhibition visitor) action of gradually pulling out threads and making the image “disappear” changed the meaning of the work and took it far beyond the boundaries of capturing individual facial features.

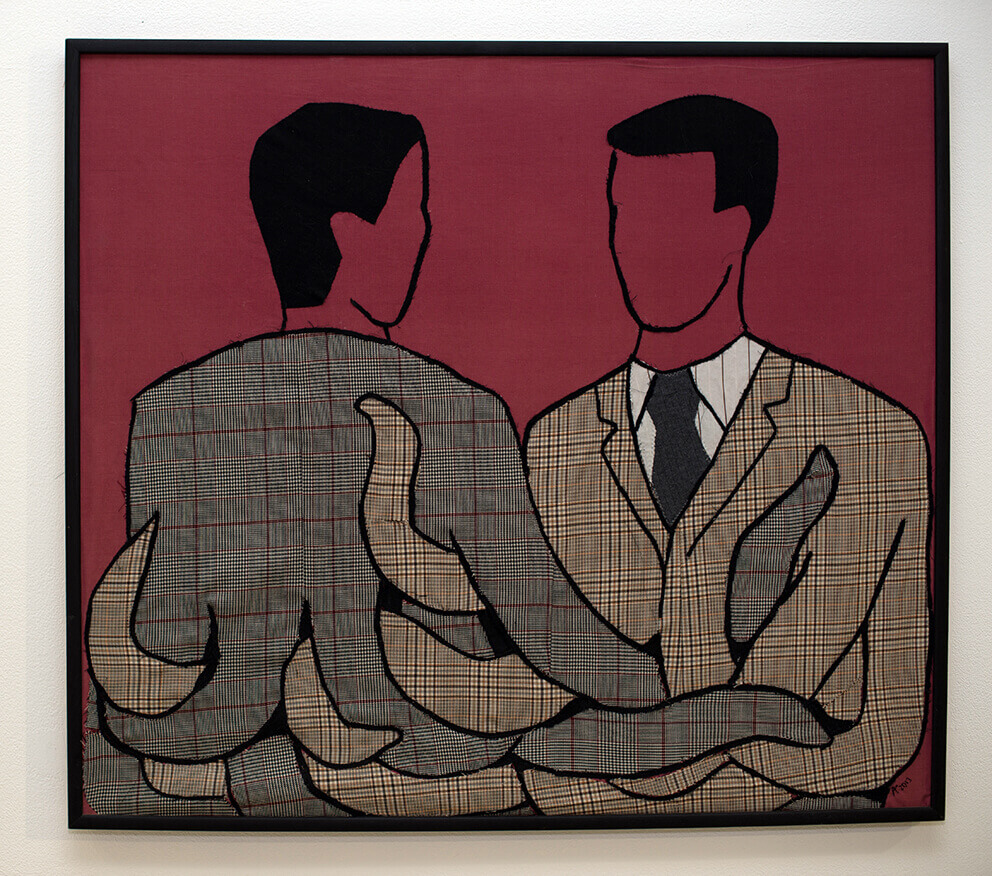

Not ripping, but un/re/weaving, not discarding, but piercing, taking possession of and reusing – there are many such deviations at the exhibition. In Alina Kopytsia’s series of textile collages, “Man’s World,” she plays with the image of a business suit, which she sees as a knight’s modern armor of masculinity. Embodying prestige and status, this symbol of the modern elite provides access to power and economic resources, forcing the wearer to pay for it with excessive stress and a narrow list of what is acceptable for a man. We as a society haven’t even begun to discuss male “patterns.” The collage “Business Relations” is a visualization of the captive hold masculinity has on men.

Textile in itself has strong metaphorical potential for shifting perspectives and meanings by being a medium that on the one hand appeals to something familiar, and on the other allows you to create works of plastic expression and unexpected content (like in the textile sculptures of Louise Bourgeois). This is the approach that Oksana Briukhovetska takes in the project “Suit Jackets,” where she introduces lace, flowers, and other colorful “women’s” things into a stereotypically male article of clothing. By “flowerizing” the jacket, the artist shifted its meaning, made it a strange (queer) object that goes beyond standard boundaries

I feel that in real life we use similar strategies of deflection and penetration more often than we realize. Life consists of labor, labor creates us, and labor consists of unique and repetitive actions. Their repetitiveness has potential for enslavement, while their uniqueness is a source of freedom. The balance between the two has to be found every time anew, and only the long-term will show the social configuration which the aggregate of individual decisions will create.

Translation from Ukrainian to English: Chrystyna Kuzmych

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)