Chișinău, the Capital of Moldova, is a mixture of Moscow and Grajewo. The best of what both communism and capitalism had to offer to the Moldovan nation. The Moscow style is a classic gigantism: curbs so high they beg for their own stairs between the street and the pavement; classic buildings, huge and monumental. And Grajewo is a traditional “Polish outdoor” – ugly billboards not matching the surroundings, a gaudy capitalism, kiosks and shops plastered with banners that make you think the designer wept as he was making them. That’s what I remembered from Grajewo but the exact same thing can be seen on the Warsaw motorway towards Krakow. Storefronts decorated with tiles that make them look as a lavatory inside-out. In Chișinău those two styles are accompanied by a third – gigantic blocks of flats. Similar adorn Moscow, Kyiv and probably many more further east. You must admit the architects had a field day. The Soviets had sent our architects shorter rulers.

I started liking Chișinău on the very first day as I drove downtown from the airport and passed the city gates: two gigantic triangular edifices hugging the motorway that make you remember Lord of The Rings. I started loving Chișinău when I discovered the Eye of Sauron:

A strange city in a strange country. What do we know about Moldova? That a prince from Dynasty TV series used to live there? I’m not even sure if I should mention Blake Carrington and his house to my friends from Chișinău. After a while I think it’s better to tell them about Dynasty than to admit that in Poland Moldova is associated with kidney selling. I do not say that. I am ashamed. When I accidentally spill the beans a friend replies quietly that he did hear of such issues. We leave the subject.

Walking down the streets of New York I think I recognize the buildings and paths – I saw them countless times in Woody Allen’s films or in Sex and the City. When I was in Rome watching the Colosseum I had the impression I know the place I’ve seen numerous times in history and art books. In Moldova I chance upon mosaics on the walls of a subway by the Stefan cel Mare Street and I have a feeling I know such mosaics. They were on a side of a culture centre but were plastered over. They still can be seen on the side of Gdynia train station. In Chișinău I pass concrete flower beds in front of government offices and I recognise exactly the same ones stood in front of the offices in my village.

Moldova is a physicality that I recognise from my childhood experiences and travels around Poland. It’s the social modernism, tower blocks and wild capitalism that I grew up in.

Downtown Warsaw looks modern now but Poland is not only Warsaw. I’m not from the centre of the capital that’s probably why I feel secure and well in downtown Chișinău,

Bogumił Luft, the Polish ambassador to the Republic of Moldova in 2010-2012, in his book Romanian in Pursue of Happy End recalls that Moldova used to be “one of the wealthiest soviet republics and the local wines, vegetables, and fruits used to flood the whole Soviet market. Well known in Poland and other Eastern bloc countries Sovetskoye Shampanskoye was actually a Moldovan brand”. “Being Moldovan was a pride” – he adds.

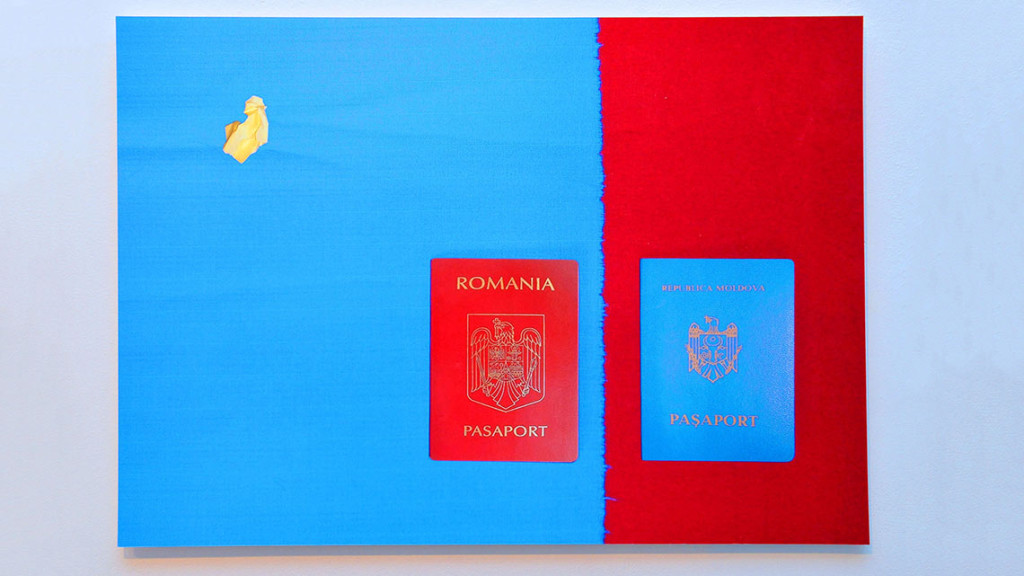

I’m going for a beer with fellow Moldovans. There are five of them at the table four of whom have a double citizenship of Romania and Moldova as the Romanian citizenship gave up till not long ago the only possibility of visa-free travelling in Europe. The passport was relatively easy to come by – almost everyone in Moldova has a grandmother, grandfather, aunt, uncle, some close relative in Romania. And Romania is in the European Union so you don’t need an entry visa. What visa requirements are I know very well from Ukraine where Krytyka Polityczna runs a culture centre and a publishing house. For years we’ve been battling administration and Polish-style political philosophy of Schengen which is dealing with our inferiority complex through offensive treatment of people living in the East. Since the war started pleads for help in obtaining a visa have been growing in numbers. I tell that over a beer to my friends from Chișinău. And that as a rule I help anyone I can. They tell me this could be a good business and that I would roll in cash if I was charging every invitation at the amount Moldovan middlemen do. Between 1989 and 2004 the number of Romanian citizens living in Moldova climbed from 2.5 thousand to 73 thousand. And it’s unlikely these are persons who had moved from Romania.

Since April 2014 Moldovans do not require a visa to enter the EU. I don’t know if it influences immigration. “A phenomenon of more or less steady emigration has gradually encompassed close to a quarter of the society and around a third of the GDP comes from money sent to families from abroad” writes Bogumił Luft. Moldovans leave for the West but also for Russia. Many of them speak fluent Russian a second language in many countries of the region over the years. Today many coffee shop menus are bilingual: Romanian, that is Moldovan, and Russian. When buying coffee and cigarettes in downtown kiosks I find it easier to communicate in Russian than in English. But in popular clubs I can easily order drinks in the latter. My friends from Chișinău who grew up surrounded by languages of two separate groups, Romanian of the Romance group and the Slavic Russian, and later learnt English are quick to pick up additional languages. Perhaps that’s why the selection of destinations is so broad. Many go to Russia, quite a big group to Italy, some to Romania, to Ukraine before the war. One in four Moldovans work abroad. When I talk with the friends they say that each of them has a friend or a family member living away. It would seem that for educated young people a bigger challenge is staying in Chișinău than leaving.

Emigration, language, history are subjects that perhaps don’t stir the public debate red hot but they do return in everyday conversations. During one such conversation someone recommends me one of the latest plays by Spalatore Theatre from Chișinău Moldova Independentă. Erată. The theatre plays in a room where two days ago I was at a dance party. A smoke filled basement – the smoking ban has yet to arrive to Chișinău. A small bar. A room next to the bar holds the stage. Several dozen arrive for the play. Moldova Independentă. Erată is an addendum to the official history of the country from school books. The Errata holds non-heroic stories – the stories of common people entangled in socio-political changes. The screenplay was created based on interviews, family conversations, desk research, but also based on looking closer to how the history of the country is described at school and in the media. To my dumb question what language the play will be staged in my friend replies that if it’s about history than probably in Romanian and Russian. He’s right. Bogumił Luft writes that he doesn’t want to speak Russian in Moldova as the language is “a tool of preservation of not simply Russian but Soviet inheritance and nostalgia”. One of the protagonists of Moldova Independentă. Erată a Russian living in Moldova since birth says he was sometimes ashamed to speak Russian although he knew everybody could understand him. “First you’ve proclaimed independence and separated from Russia so that you can go work there now”.

Emigration, language, history are subjects that perhaps don’t stir the public debate red hot but they do return in everyday conversations. During one such conversation someone recommends me one of the latest plays by Spalatore Theatre from Chișinău Moldova Independentă. Erată. The theatre plays in a room where two days ago I was at a dance party. A smoke filled basement – the smoking ban has yet to arrive to Chișinău. A small bar. A room next to the bar holds the stage. Several dozen arrive for the play. Moldova Independentă. Erată is an addendum to the official history of the country from school books. The Errata holds non-heroic stories – the stories of common people entangled in socio-political changes. The screenplay was created based on interviews, family conversations, desk research, but also based on looking closer to how the history of the country is described at school and in the media. To my dumb question what language the play will be staged in my friend replies that if it’s about history than probably in Romanian and Russian. He’s right. Bogumił Luft writes that he doesn’t want to speak Russian in Moldova as the language is “a tool of preservation of not simply Russian but Soviet inheritance and nostalgia”. One of the protagonists of Moldova Independentă. Erată a Russian living in Moldova since birth says he was sometimes ashamed to speak Russian although he knew everybody could understand him. “First you’ve proclaimed independence and separated from Russia so that you can go work there now”.

Russian is the primary language in… a shopping mall. The mall has become localised and one of them is called MallDova. I am impressed with the linguistic imagination. The salespeople at the shopping centre talk to everyone in Russian. Supposedly this is because when the big box retailers started appearing only the rich Russians could afford shopping there.

The language in Moldova is complicated matter. That’s what I think at the beginning. Later someone tells me that it’s nothing intricate – it’s simply Romanian.

History put Moldova in the USSR sphere of influence. For that reason Moldovan used the Russian script. In 1989 the Supreme Council in Chișinău reinstated the Latin script. The differences between Romanian and Moldovan are that between dialects. The game is about naming the language: in the 1991 Moldovan declaration of independence the official language of the state is Romanian but the 1994 constitution lists it as Moldovan. In 2003 the Moldovan-Romanian Dictionary was created but it’s rather a butt of jokes than a serious publication.

How crucial is language in forming the identity the Poles know a lot. Adam Mickiewicz did write “Lithuania, my fatherland” but he did write it in Polish. Moldovans today write their story in Romanian – furthermore the Romanian story is the closest to them. There is no Moldovan Wikipedia. There used to be but only for a short while. It was written in Cyrillic script, but since the script was abandoned the project was put on hold. The Moldovans therefore have their Wikipedia together with Romanians. They read the same webpages. They surely read the same books and watch the same, excellent, Romanian cinema. Although it’s not that easy with books and cinema. A bookstore in downtown Chișinău mainly has school books. There a few Romanian-published bestsellers and a few Russian-language classics. The cinema as you can imagine is losing with blockbusters who everyone watches on their computer screens at home. Internet is widely available. Free hot spots are available in parks, every bar; you pick them up walking down the street. No one is surprised people are sitting in a public park downloading films.

Zachęta Project Room is just hosting an exhibition entitled Waiting for Better Times featuring contemporary Moldovan art. One of the works shows a map of Europe from 2001 that is missing Moldova. Romania is simply bordering Ukraine. “It is possible Moldova doesn’t exist” reads a text on a taped on piece of paper. The 2002 work by Pavel Brail and Manuel Reader is probably still very true. Moldova perhaps isn’t present in our consciousness but similarly Poland is missing from the minds of Moldovans.

Zachęta Project Room is just hosting an exhibition entitled Waiting for Better Times featuring contemporary Moldovan art. One of the works shows a map of Europe from 2001 that is missing Moldova. Romania is simply bordering Ukraine. “It is possible Moldova doesn’t exist” reads a text on a taped on piece of paper. The 2002 work by Pavel Brail and Manuel Reader is probably still very true. Moldova perhaps isn’t present in our consciousness but similarly Poland is missing from the minds of Moldovans.

January saw a book advertised as the first thriller in Moldova. This might be a slim marketing hyperbole but the book certainly is a breakthrough in local world of writing. The author is a young Moldovan female writer – a sort of Moldovan Dorota Masłowska. Doina Lungu wrote a book at the age of 19 while being a student. A few professors liked the text, a publishing house appeared and the book was supported with Ministry of Culture financing. The opening took place at a coffee bar. One of the professors gave a speech stating that we are witnessing the history, the history of literature. We are celebrating a publishing of a book with a wine in a coffee house instead of a dusty library. The tables were populated with a popular TV presenter (whose arrival had made quite a stir that’s how I’ve learned he’s a presenter or an actor) next to a Spalatorie Theatre writer and various cameramen and photographers. After the speeches a musical recital started. We were sitting in a coffee shop named Uptown listening to American hits on a guitar and sang by a girl with a mesmerizing voice. I thought Rammstein is right – we are all living in America. I’m not sure if the professor had such a new chapter of history in his mind. I’ve looked through the book written in a language I don’t understand at all and discovered well-known names: Krakow, Wieliczka. It appears “the first thriller in Moldova” is taking place in Poland. I’ve asked Doina Lungu for the source of the idea. She wanted the plot to take place in a medium-sized town outside of Moldova. She was considering Hungary but someone suggested Wieliczka.

Doina was never in Poland. She found Wieliczka on GoogleMaps and thought it would be a good site for her novel. The same way Chișinău is distant and unknown to us, Krakow is distant and unknown for a Moldovan teenager.

Moldova straddles the EU-Russian border. An Association Agreement was signed on June 27th last year. The last parliamentary elections, in November last year, the majority of seats were awarded to three pro-European parties that failed to reach an agreement however. When a minority government of two of the parties was decided in January with a possible support of the Communist Party the electorate protested. My friends wouldn’t let go of their phones trying to learn what was going on in the parliament. They are irritated but not particularly disappointed as they don’t trust the politicians anyway. They were counting on and independent Oleg Brega winning a seat. Theoretically the law gives such a possibility to any independent candidate who wins 2% of the votes. Brega, an activist and a social advocate had managed to secure 0.9%.

The minority coalition is extremely volatile. Russia is currently preoccupied with the war in Ukraine so it exerts less pressure. The European Union seems to act only when it tries to block Russian actions. But neither does Russia need Moldova nor is EU interested. With the friends I joke they should take advantage of the fact that “Western regulations” have yet to arrive in Moldova and they can still smoke in bars or can buy a good coffee strait from a car-turned-coffee-bar. Identical cars are all over Kyiv. Such things are only possible in places where sanitary regulations are missing or the existing ones are not respected. I visit the old Orhei and a rock-cut temple. From the inside you can exit onto a stone terrace. “The European Union will come and will make you erect barriers” I think.

When I tell a friend from Moldova that I surely want to return to Chișinău he is surprised the same as I am when someone from the West says they like it in Poland. I always assume it’s just good manners. I am usually right. He is also right. I like Moldova but it’s because I feel right at home there, Chișinău shows all the scars of the transformation. The mosaics are yet to be walled over. Shopping malls already stand next to them. And between them tower blocks with self-made balconies. The streets are a Swiss cheese of potholes, sidewalks crumbling down. Using ordinary standards Chișinău is ugly. But it has its own imagination. The city gates and the Eye of Sauron, lakes and the incredible Botanika district, legendary buildings like the Cosmos hotel. And there is an issue in Moldova that matters to people. There is the search for a narrative. I miss every walled up mosaic in my neighbourhood. I hope the Moldovans will save their own.

PS. There is also an alternative history of Moldova – since the matters were bad the government had sold the country and for the money made put everyone into a space ship and settled on Planet Moldova:

PS.2

The song goes on like this: “Today Moldovans are looking straight in the eyes of an American, Englishman, Frenchman, German and Japanese and they only see a single thing – they all envy Moldova. Moldovans are proud and they can tell that Moldova is better than any of the other countries”

Translated by Konrad Zwolinski.

The Waiting for Better Times (Czekając na lepsze czasy) exhibition is open in Zachęta Project Room in Warsaw till April 12th.

Article originally appeared in Dziennik Opinii nr 86/2015 (870)

Follow Political Critique

[one_half]

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

Follow @krytyka

[/one_half_last]

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)