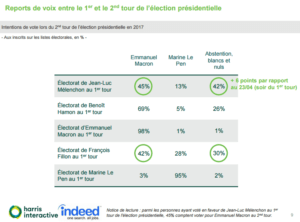

The true winners of the first round of the French presidential elections were the pollsters. After being berated for their failures to predict the victories of both Brexit and Donald Trump, this time the figures that circulated during the election campaigns were confirmed at the ballot box. This was particularly noteworthy given the proximity of the four candidates, who were within four percentage points of one another, a situation which enabled the surprising first place victory of En Marche. It was a competition that showed how much French politics has been transformed by Hollande’s presidency. It was also a situation polarised between radical choices (together Le Pen and Melénchon surpassed 40% of the votes) and moderate perspectives (if to Macron’s votes you add those of the traditional parties of Fillòn and Hamon you arrive at a substantial 50%). This is a scenario that could likely be repeated in the next round, which polls see Macron winning by 60-40 over Le Pen, despite some significant doubts.

For in reality the match is far from over. Even if the numbers show that the National Front will likely be overcome, on the 8 March we will see how strong that threat will remain in France, particularly in view of the formation of the National Assembly in June. Certainly, a resounding victory for Macron would be very different than a more hesitant one against a candidate who, in the recent past, has managed to reclaim legitimacy for her party.

In 2002 Jean Marie Le Pen stunned the world by making it through to the second round of the presidential elections against Jacques Chirac, where ultimately 82% of the French rejected him. That year the National Front closed the first round with an unprecedented 16% which shocked the political class that had underestimated this ‘anti-systemic’ party which had been delegitimised by the French democratic system. Aversion to the National Front was in fact so strong that the Republican leader refused to debate with his opponent, considering him completely outside of the usual democratic dialogue.

He above all must take considerable responsibility for normalising the presence of a far-right party, xenophobic populism, inside the political system of one of the founding countries of the European Union.

15 years later, something has changed. The Front National candidate has not only been welcomed with open arms into televised debates, but set the agenda of the entire electoral campaign. Like last Sunday in Amiens, when she ambushed the leader of En Marche in a factory of Whirlpool, a symbol of the damage of globalisation, and through tactical alliances with other parties. Just look at the deal with Nicolas Dupont-Aignan’s nationalist party – who in the first round won 4.8% of the votes and to who was guaranteed the role of Prime Minister in the case of victory – masterminded by Florian Philippot, one of Le Pen’s closest advisers. He above all must take considerable responsibility for normalising the presence of a far-right party, xenophobic populism, inside the political system of one of the founding countries of the European Union.

This strategy is capable of overturning if the not the result then at least the meaning of this Sunday’s vote. Historically, as in 2002, the second round of the French presidential elections works to eliminate the ‘least welcome’ candidate on the basis that this is a more direct choice than that of the first round. It is precisely around this pivot that Le Pen’s electoral campaign continues to turn. Yet with the National Front normalised, paradoxically, it is Macron who needs to defend himself. The leader of En Marche, an ex-banker and Hollande’s minister of economy, is the champion of the elite, of the pro-European French oligarchy and those who have benefited from globalisation: an antagonistic enemy to the poorer classes according to Le Pen’s argument.

Indeed the cheers of the EU’s gatekeepers represent perhaps the biggest risk for Emmanuel Macron. With the transformation of the presidential elections into a sort of referendum on Europe, as Pierre Moscovici European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs put it, there is a risk of uniting a Eurosceptic opposition that has already obtained victory in the recent past (in 2005 the ‘No’ to the European constitution saw an alliance between Dupont and Le Pen). Voting for the National Front, which is clearly behind even in the intention of those who see their politics outside of the ballot box, may be the only strategic choice for such a politics.

A National Front result of over 40% would risk turning Macron’s success into a Pyrrhic victory from a legislative point of view.

And here we arrive to the point. A true victory for Macron would require not splitting France more than it is, both in terms of Sunday’s result, but also in dialogue with the forces that came out to vote on 23 April. As far as the first point goes, it is clear that a National Front result of over 40% would risk turning Macron’s success into a Pyrrhic victory from a legislative point of view. One of the major doubts surrounding Macron’s movement is his weak performance in areas that make the appointment for the National Assembly far more complicated than the presidential elections. The En Marche campaign is strongly focused on Macron’s personality, a difficult strategy to replicate at a local level, and which would be even less effective in the case of a marginal victory. Likewise, an ‘honourable’ defeat for Le Pen would give renewed impetus to the anti-European movement with implications on the next electoral appointment, and ultimately on legislation.

It’s evident that Marine Le Pen, sustained by a strong popular support, would be able to dictate the future agenda of French politics even further. The long list of endorsements received by Macron in the attempt to isolate the National Front, on the other hand, risks rebounding. Put bluntly: votes for Macron could be seen as the sum of diverse political forces that have chosen to lean on him, while those for Le Pen could be considered more substantially ‘her own’. This would complete the party’s process of normalisation, launching the National Front as a leading opposing force if legislative elections were to reinforce the energies behind their campaign. The second point concerns the response of the centrist leader who must find a way to engage in dialogue with his opponents on the left: supporters of Jean-Luc Melénchon. One early example of the difficulty here was revealed on Monday when the radical left leader put forward his request to revise the labour legislation put forward by Macron himself. The leader of En Marche responded with a fairly emphatic refusal.

The ability to manage relations with forces that did not support him will be decisive for Macron’s now probable government, which has reached this point by exploiting the image of inexperienced outsider. Because while En Marche has successfully resonated with the support base of traditional parties, everything is still to be proven about how he can communicate with the other half of the country, that which rejected moderate solution by choosing Le Pen or Melènchon. The polls show the size of this challenge. Macron’s capacity to meet it will have consequences for both the future of France and Europe.

This article was translated from Italian by Jamie Mackay.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)