A petite boy called Diogenes has both of his hands tied with belts to his bed. Mary is 12 years old and has spent her entire life locked up in an empty room without ever seeing the sunlight. Others play inside cages; 2m-long bed-cages with wooden bars. They have never left this prison. They wear diapers 24/7 and are bottle-fed. Some of these residents are already 30 years old. They are on medication; they swallow up to 30 pills a day without being able to articulate a single word, a result of chemical suppression. The terrible smell of incarceration and bodily waste does not emanate from the video that I am watching.

These images were recorded at the Child’s Care Center of Lechaina, a state-run home in the Peloponnese, Greece, in November 2015 by the disabled director and activist Antonis Rellas. He shows them to me today, two years after the recordings, as he completes his documentary entitled From Asylum to Society. This material motivated me to travel with him to Lechaina in July 2017. The residents are the victims of the state’s “Welfare” program and institutionalization scheme concerning mental health patients and disabled individuals in Greece. As newborns, most of them were abandoned by their parents, either because their families could not fulfill the needs of a disabled child or because these children, like Hephaestus, were not “normal” babies, and so were thrown out of their homes and into the sea of institutionalized life.

An ongoing crime is being disclosed

The Child’s Care Center in Lechaina was founded 27 years ago. This story is not news; on the contrary it is the epitome of an ongoing problem in Greece. In 2009 European volunteers who spent several months in the Center filed the first accusations. Following an investigation, in 2010 the Citizen’s Advocate drew up a report of findings of blatant violations of fundamental human rights at the Center. 2011 was the first time that reporters entered the Center with a TV camera and the situation was described as reminiscent of “medieval times”. Finally, in 2014 world-wide outrage grew after a shocking BBC report that showed children locked up in cages like wild animals in Greece, at the dawn of the 21st century.

After the BBC report, Catherine Papakosta (of the New Democracy party), under-secretary of the Ministry of Health, visited the Center. Activists and medical staff reported that “the result was to install an interior surveillance system, completely useless and now out of order”.

Director Antonis Rellas is a member of the Greek Emancipation Movement for the Disabled Zero Tolerance, a group of activists who peacefully occupied the Center for four days, on 4 November in 2015, in order to take action.

“The issues concerning the situation in institutions were very well known to us before we decided to take action. The Center in Lechaina happens to be the most representative example of the institutionalization of marginalized, [an example] of which we are not proud of at all. Disabled individuals survive in conditions of terror and torture, cut off from the world, tied up in cages, living an inhuman life. It is no coincidence that the majority of the 70 state-run institutions across the country are located outside city limits, so that no one remembers their existence. The fundamental human rights of disabled individuals have been declared by the UN Convention which is also state law, but a crime has been committed for 27 years now by each and every government: it seems as if time was frozen.

Politicians limit their efforts to declaring their sensitivity for these “special” children, without making any substantial form of intervention in order to terminate institutionalization. For these reasons we decided to occupy the Center and demand the termination of the exclusion and the torture of our fellow-disabled,” according to Antonis Rellas.

When I left this place I left a piece of me in that cage, a cage that will follow me.

Apart from the fact that this is a political and human rights matter, for some activists it has also been personal: “I went into the cage, lay down and cried. My whole life appeared before my eyes in those seconds. I realized that it was only by luck that I was not one of them. I am on the outside by mistake. If Vaso, my mother, back in 1973 in the city of Patras, a few miles away from here, had not cursed and kicked out her brother-in-law, who had recommended that I be placed in an institution he knew of nearby so that she wouldn’t suffer, I would be one of them. Why am I crying? Why do I get angry? Why am I ready to fall apart as I wait for the photo shoot? The answer is simple. Because when I left this place I left a piece of me in that cage, a cage that will follow me,” Andrew Kouzelis,writer, sociologist and activist with spastic quadriplegia, wrote in November 8.

In Lechaina

The next day, after a three-hour trip, we arrived from Athens to Lechaina. It is a three-story pink building, a few meters away from the Electricity Substation and far from city limits, with a dome and a Christian cross at the top. There were a few swings in the yard with no children on them, an ambulance parked off to the side and some olive trees. We were told that when a resident dies they plant an olive tree.

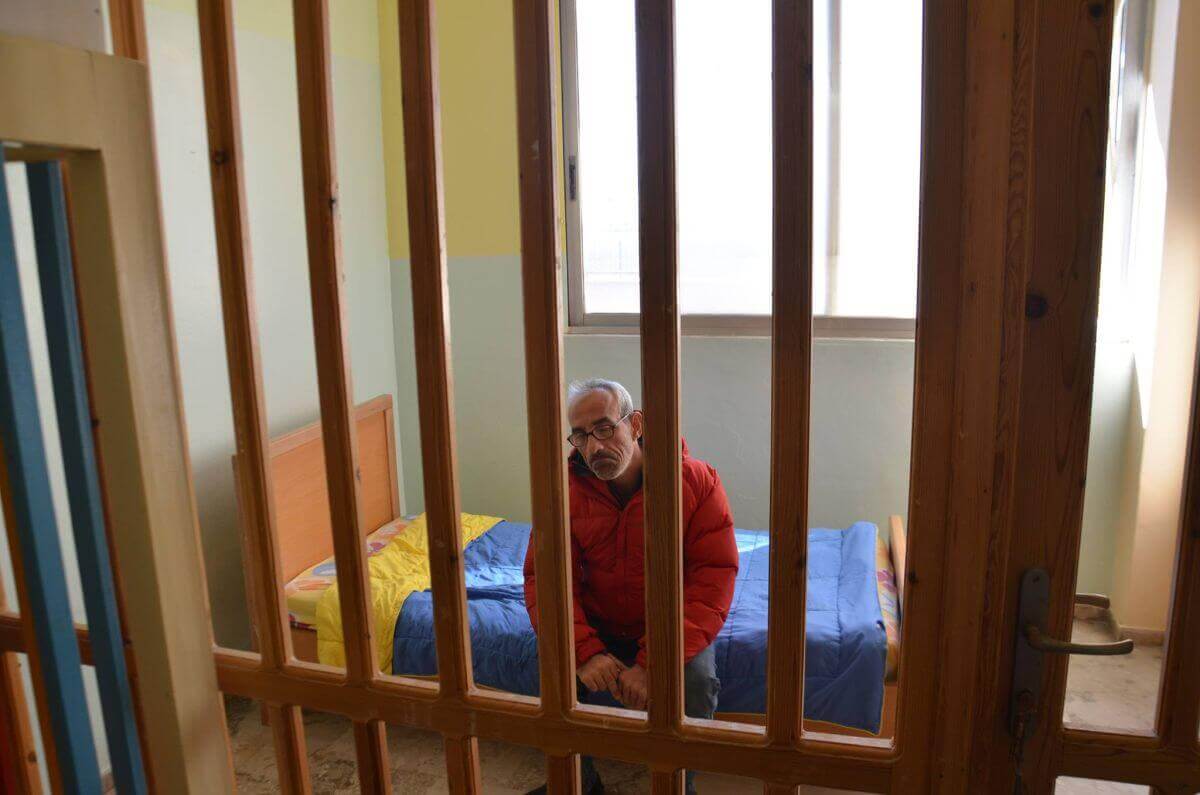

It is clear that, after the occupation and the pressure from the activists of Zero Tolerance, significant changes had been made, such as open bed-cages, reduced medication and minimized mechanical restriction. Residents seem to have come out of sedation, like dolls suddenly infused with life. Some articulate their first words and smile while others eat and drink by themselves during lunchtime. Some had never moved their limbs before the activists’ intervention. There is also air-conditioning, since it gets very hot during the summer, and central heating in wintertime, another result of the activists’ demands.

The staff has been informed of our visit so every space is neat and there are even some decorations. When we arrive, some residents, or “beneficiaries”, as they are called, spend their morning rest time in the playroom filled with air-mattresses and a TV set. There are seven or eight residents per room and they keep no personal objects. Only a girl named Canella, whose legs are tied up, has a few paintings and teddy bears. “Some of them receive visits from family members,” Antonis Rellas says while he guides me around the building.

Most of them are forgotten by their families, as if they never existed. While we make our way around I see that the room where 12-year-old Mary was locked up is now the physiotherapy room. Mary has now been transferred to an institution for minors.

The place is still a clinic that belongs more to the Dark Ages, or a scene out of a dystopic movie.

A man named Prodromos is 34 years old. He was abandoned as a baby in a small basket and lived in an institution for minors until the age of eight. At the time he fell off the 4th floor of the building and as a TBI patient (Traumatic Brain Injury) he was transferred to Lechaina. He smiles and asks for “sea”, “closet” and “nightstand”. One of his wishes is granted as, that afternoon, we take him for a walk by the sea, which might be a first for him –who knows…

The place is a far cry from the hellhole activists encountered when they first occupied the building two years ago. But anyone who cannot swallow the idea that these people are not really people, and who reflects that every such institution is called home by those who live in it, will realize that the place is still a clinic that belongs more to the Dark Ages, or a scene out of a dystopic movie.

People as objects in the trashcan

George Tsiakalos, professor of Pedagogy at Aristotle University in Thessaloniki, has said that residents of Lechaina “could talk, laugh and go to school” if they did not suffer that tremendous damage of institutionalization. George Nikolaides, director of Mental Health and Social Welfare office at Child’s Health Institute, is the psychiatrist who has been officially in charge of the intervention program in Lechaina since 2016. I asked him how these individuals would have been today if they had not lived through medication and mechanical restriction, and also if this really is a case of torture.

What happens in Greece is that we pretend to conform to rules and regulations, but things never really change.

“Of course, totally. How does it look for a person to live for 365 days constantly in a cage or have their limbs tied up? What would you call that? This is clearly a violation of basic human rights and, in a sense, a crime for which Greece has been arraigned in all national fora by the United Nations, the Commissioner of Human Rights of the European Council, pertinent bureaus of the European Committee and so on. What happens in Greece is that we pretend to conform to rules and regulations, but things never really change. The first organized protest took place in the late ’90s, coordinated by a group of professionals and activists. The Government and the Administration of the Center managed to scatter the group and some protesters were even arrested. The only thing gained by the protest at the time was the replacement of metal cages with wooden ones,” Dr Nikolaides recalls.

He goes on to explain that “These individuals were treated by the system as if they were objects, with no expectations or individual characteristics. They were objects. What strikes me about my experience of working with these people is seeing the moment they awake and become subjects who express their preferences, and take initiatives as simple as reaching out for a specific person to touch and connect with by choice, or talk for the first time in years. What Mr.Tsiakalos had said about education is true, and in fact two of the minors go to a special education primary school.”

“The Lechaina Center has been the trashcan of the Welfare system from all around Greece; every lost case was sent here. Of course there are some clinical cases that are quite severe, with multiple mental, cognitive and motor issues; on the other hand years of institutionalization, mechanical restriction and chemical suppression hinders language acquisition and cognitive development. Just think that, when we first intervened, there was a young man who had been tied up for 21 years. Everyone was so isolated and deprived of basic human touch that with just a little concern, care and communicative engagement there has been significant improvement.”

I asked for a specific example and he continues: “There is a teenager with an oversized skull, limb hypertrophy and a metabolic disorder that makes his bones brittle and which results in multiple fractures and an inability to hold up his neck. After he suffered a fracture, the courts accused the staff of negligence. So the decision was made to have him constantly tied up so that he would be safer. As we speak, he is no longer restricted in a cage, but free to touch, feel and express his emotions. The solution was a specific moon-shaped pillow that helps him stay steady. I sometimes watch him tidying his things.”

Inevitably, I ask Dr. Nikolaides if there are members in the Greek scientific community who still recommend mechanical restriction and strong medication. “Yes” he answers “But individually and not in terms of a broad scientific discussion. There is a misleading notion about these institutions that they are some sort of hospital, especially among medical stuff. On the contrary, the residents see these centers as home. If a professional thinks he works in a hospital, a proper response to a resident walking around is “What are you doing? Why aren’t you in bed?”

Institutions as Barracks

Today the Center of Lechaina has 44 residents, the oldest of whom is 48 years old. There are four minors among them. Most of them were initially placed in this Center or in similar institutions and never came out. These residents have cognitive disabilities, and bodily and motor impairments. Here there are also individuals with sensory disabilities, such as impaired vision or even blindness. According to the psychiatrist “it is unacceptable that they live here. They do not belong here, because the Center lacks basic infrastructure for people with sensory disabilities.” Similarly, Dr. Nikolaides continues, “There are clinical cases that God knows how they ended up in here. There are patients with autism, to the extreme of the spectrum, and it is such a shame to have them institutionalized.”

According to the latest research conducted in 2014 by the NPO Rizes (Roots) there are 2,825 children institutionalized in Greece, 883 of whom are disabled.The research showed that disability was the main reason for institutionalization, according to the participants, after negligence and abuse. Of a total of 85 institutions that undertake care of children, only 28 are supervised by the State, while the rest are run by NGOs or the Church.

At least a part of staff appreciates the changes, and acitvely participates in the effort.

The Lechaina Center has a staff of 60 people, 25 of whom are responsible for the immediate care of the residents. Most are not healthcare professionals of any kind. The rest of the staff consists of administrative employees and technicians. As Dr.Nikolaides says “when we arrived in the Center last year, there was a speech and language therapist among us and the response of the staff to the presence of a professional was “What could a speech and language therapist do here? They don’t even speak!” But the good thing is, and this should be mentioned, that after a year, at least a part of staff appreciates the changes, and acitvely participates in the effort.”

We spent the night at the Center as guests. In the room I stayed there is a bed, a basin and a wheelchair. There are some stickers of cartoon heroes on the wall and a drawing saying I Love Love.

When faced with the brutal images of institutionalization, we look away and attempt to forget them.

In the morning all the residents wake up at the same time, eat the same meals and go to sleep at the same time, in an impersonal environment. “When you live in mass conditions, you inevitably follow a specific and quite strict program. Even if we try to improve the environment, there is always an obstacle because of space limitations,” explained the psychiatrist. He continued: “People should go out. Now they go out only for medical reasons. This is completely wrong, because, for example, there are residents with Down Syndrome who, because of long-term institutionalization and a lack of education and socialization never developed fully. Today individuals with Down Syndrome normally work, drive, get married, have friends, make love.”

Disability issues are left on the sidelines of institutional agendas, but also, unfortunately of activist ones. Stories about disabled individuals are used either to add drama to the evening news or as an oportunity to glorify “everyday heroes”. When faced with the brutal images of institutionalization, we look away and attempt to forget them. But emotion means nothing if it is not followed by the steps towards improving the situation.

The Battle against Institutionalization – Zero political action?

“The Ministry is very well informed about the conditions and the problems institutions face. We know that the two most important issues are the lack of medical and special education professionals and infrastructure issues. A general meeting of administrators of all such institutions in the country has been scheduled for November in order to compile a detailed account concerning these problems. The aim of the strategy of Ministry of Labor, Social Security and Solidarity is to accomplish the de-institutionalization to the greatest extent while still providing for those in need of the appropriate medical care, and all future actions are to be based on this decision.”

This statement above was the answer of the Secretary to the activists of Zero Tolerance on November 5 in 2015, the second day of the occupation of the Lechaina Center.

On the one hand, the Ministry is fully informed about the conditions in Lechaina. On the other, however, though the Secretary mentions the key-word de-institutionalization, the solutions that are presented seem abstract and disproportionate to the problems. A neat and tidy hellhole is still a hellhole.

Activists and professionals working in Lechaina both agree that residents must receive personalized intervention and special care in order to be prepared for transition to an open and broad care center. How is it possible to move beyond the present model of institutionalization and isolation? Dr. Nikolaides and his colleagues have recently presented their proposal to the Greek government, the European Committee and relevant entities concerning a full plan for the replacement of the Center with smaller houses, different accommodation and better living.

The history of mental health reform in Greece shows that a smaller care center could be worse than a bigger one.

As Dr. Nikolaides says “The proposal took into account the needs of each and every resident of the Center of Lechaina. We did not consider them as a group, but as individuals with specific needs. Some of them, for example, can be transferred to foster homes. In order for the plan to work, we need to have a transition stage, a smaller center. Unfortunately, the history of mental health reform in Greece shows that a smaller care center could be worse than a bigger one. This is why this proposal includes a process of re-education of staff and residents, so that eventually the residents can be reintegrated into society. Also, it is essential to include a prevention program to enable families to have access to the necessary intervention programs in order to avoid more petitions for institutionalization. We have also included a certain budget and a time frame in order for the program to be possible and we wait. But we cannot wait forever…”

“The program is supported financially by the British Organization Lumos, which is run by the Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling. But it is unacceptable for this project to be supported financially by a foreign organization; the Greek State must share responsibility for this. We receive expressions of interest on behalf of the government, but they need to take action toward the de-institutionalization process. There is no use in dissolving this center because of negative publicity without aiming towards an inclusion policy.”

There are many private care centers to which we have no access, nor do we have information about their form and function.

As far as financial planning is concerned, Dr. Nikolaides says “The exact budget of the Lechaina Center is presently vague, as it is for each and every state-run care center. This is the case because of the multiple financial resources centers receive. Given the present data, the amount of money the Center receives is up to 1.5 million Euros annually, which amounts to 2,600 Euros per month for every resident. For our proposal the budget is estimated to be as high as 2.2million Euros for relocation and support, with another million Euros added to that to cover intervention and support programs around the country to avoid institutionalization going forward. There must be no center in the future that resembles the Lechaina Center, neither state-run nor private. Needless to say that in addition to the regulated state-run institutions, there are many private care centers to which we have no access, nor do we have information about their form and function.”

“The main priority is the absorption in the new centers of the medical staff who are part of the system already, but there is also a need for hiring professionals such as psychologists and social workers who are not presently included in the staff of the Lechaina Center, according to Dr. Nikolaides. “We also try to overcome some of the obligations derived from the Memorandum. It is essential for the state to acknowledge the need of staffing with special education scientists, despite the general limitations on hiring in the public sector.”

In July 13, the assembly of the Greek Communist Party George Lamproulis directed a question in Parliament to the Under-Secretary of Ministry of Labor, Social Security and Solidarity concerning another care center similar to Lechaina, the Sanatorium of Chronic Illnesses in Skaramanga. Unfortunately, his statement reveals the ignorance of most of our society. “The building in Skaramanga accommodates 29 residents, while there is room for more. Why don’t you improve the infrastructure and hire personnel in order to put more children in it?” The under-Secretary answered that large care centers belong to the past, while today “There is need for terminating institutionalization, because the solution does not involve the improvement of these institutions,” referring here to the Lechaina Center as well. “De-institutionalization has already helped many children, according to their families. Institutions cannot be seen as lost soul repositories; it is essential to interact with society”. These were the exact words of Theano Fotiou, which raised expectations for action on behalf of the Ministry.

Asylum and Society

According to Antonis Rellas, “There is an ongoing discussion about closing down the Center in Lechaina, but we are not really sure if the Government is actually planning to do so.” Dr. Nikolaides is also not convinced that the State will take action upon this matter “because of the bureaucracy and malfunction of Welfare in Greece” and the failure of neoliberal politics in terminating institutionalization.

In my opinion, there is no Social Welfare Program in Greece and there will never be.

As he explains, “ there is no Social Welfare Program in Greece and there will never be. There are few nonrecurring support structures and centers across the country, and that’s it. In the beginning of the 20th century, there was this charity network supported by great donors. After the Second World War Queen Frederica founded asylums for child protection, in order to control and prevent the spreading of Communist ideas. As a result, these asylums were promoting nationalism and religion. In the ’80s there was some kind of progress in health care, but social welfare became more and more of a bureaucratic affair. For example, I visited the Center of Lechaina and they told me that an incoming patient had just been approved. So I asked if anybody had assessed the child or talked to the family. They answered “No, but we checked these”, showing me a pile of folders with all the necessary information. In other words, decision making process about placement of a child happens only through paperwork. In the ’90s the NGOs were suddenly thriving and everybody felt safer with the idea that somebody else, and not only the State, would be considering society’s needs. It is shameful that no government has ever made a breakthrough in Welfare.”

As far as de-institutionalization planning made by neoliberal governments, a significant case was that of Reagan Presidency (1981-1989) in the U.S.A.:

“They threw residents out of the mental hospitals after packing them with a small amount of pills and a friendly wave goodbye. As a result, most of them died within the first year because they had no support or the capacity to survive by themselves, while the rest lived in the streets. It is not at all difficult to make the wrong move and put groups of people in danger, even in worse circumstances than the one described. Given the fact that our country has also been accused of negligence at the Lechaina Center, if any effort at terminating institutionalization is not planned very carefully, it is likely that poltiician like Reagan could come along and make all the wrong decisions involving de-institutionalization in our country. Total disaster…”

For two years, Antonis Rellas has filmed the living situation for residents in Lechaina, ever since the public revelation of the first images that showed the horrible situation in that hellhole. His documentary From Asylum to Society will be presented in Greek and international film festivals starting next November and is supported financially by the Emancipation Movement for the Disabled Zero Tolerance and the Greek Movement of Disabled Artists.

In his own words, “Our goal is to get all these images out to the public in order to raise awareness and make people realize that everyone is responsible. We need to motivate individuals who see this situation as criminal to take action and help towards this effort. If we can transform the Center of Lechaina, then we can transform all the others as well”.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)