I like austere bars. Bars without affectation, bars that have survived in the antipodes of the cute cafeteria or the pretentious gastrobar, so fashionable nowadays. I like them, above all, because their aesthetic disability allows their guests to relax. And there is something in its decadent and neglected atmosphere that, as a woman, I envy. It is a privilege that their clients are used to and are no longer aware of. It is all about a certain attitude: the way in which these men can occupy the public space and, drinking or drunk, expose their loneliness and miseries to a staring bar counter without any signs of shame or fear.

Loners and drunks in public space cause no alarm whatsoever. They do not attract attention. They are not prey to abominable lycanthropes and other predatory fauna. Nobody bothers them. They are allowed to get tipsy. They have the extravagant privilege of being able to do their own thing, absorbed and drunk, while occupying the public space. Therefore, with blind hope, I regularly go to these bars: to see if I, a woman, can also acquire that right that is still a privilege of men and be infected by that exceptional experience of drunken and sedentary solitude in which nobody comes to bother me.

It happened one morning while I was drinking coffee in one of these bars. I heard and saw the initial reports about the trial for group rape at San Fermines 2016 of a woman who was just coming of age . The images that the television broadcast were taken prior to the abuse and showed a citizen who, like any of these native bar people, was experiencing drunken and settled solitude, this time on a bench in a a square. With a very subtle difference: she, as a woman, was not left alone by the rest of the world. She had the misfortune of being harassed by five heartless men.

A man of about fifty was sitting next to me at the bar, also having a coffee. Disgusted by the news, he looked at me in anguish. I looked back at him: we were both unable to process what had happened. At that moment, the television broadcast a fragment of the trial. The victim’s testimony was read. Like a mantra, like a desire that yearns to become reality through its repetition, the victim reiterated on countless occasions that she did not want to be there and only hoped that everything would end as soon as possible so she would be able to return home.

Can you imagine Jews who survived the Holocaust having to prove their condition of victimhood by showing that, during every moment of their hell, from the beginning till the very end, they fought to escape the camps? Can you imagine a victim not only had to prove that she was abused, but also justify why she submitted to the conditions imposed by the dominators?

Under this requirement, and by ignoring the master-slave relational dynamics —a terminology proposed by Hegel to thematize complex and asymmetric intersubjectivity — we would be unable to determine whether the members of any oppressed group are to be considered victims. Under such an assumption, unless one resists any threatening situation with unbreakable determination, one wants and deserves the evil that is inflicted. This is a perversion that, after going through hell, a victim still has to endure: to bear the guilt of the damage done to him or her, and to be forced to prove his or her innocence.

The man at the bar and I both felt miserable hearing the testimony. Unwittingly and in unison, we both found ourselves asking the waiter to change the channel. This unexpected solidarity with the victim reminded me of the legend of Lady Godiva: she was faced with the obligation of riding naked on horseback in front of the whole community and the people responded by staying in their houses as a sign of respect, so as not to further upset the forced nakedness to which she had been exposed.

Listening to such a narrative and the morbid talk shows that were shown on television was undoubtedly obscene. But there are times when limiting oneself to closing one’s eyes and ears to misfortune does not help to repair a traumatic experience, nor to disarm the dominant ideology that allows such acts of barbarism and their consequent morbid discussion by society. This is the reason I’m writing this text. To support this survivor.

The origins of ‘consent’

The trial of “La Manada” is capable of sickening the most hardened and stoic of bellies. During its development, the defense resorts to febrile and delirious arguments, more fitting for a hot-headed pornographic novel than a State of Law, trying to exculpate five people who, in total numerical superiority and intimidating attitude, committed and recorded a group rape of a person who simply had the tremendous audacity to behave like one of my fellow barmen: she sat drunk in a public space and decided to settle down in the bench of a square one night of San Fermines with 0.91 grams of alcohol in her blood.

These five men and their lawyer intend to interpret an execrable collective violation as a voluntary, frivolous and playful gang-bang. Do they take us for imbeciles? Do you think that public opinion and the judges on duty are ignorant, condescending, narrow-minded and timorous enough not to know how to distinguish a group rape from a consensual orgy?

Unfortunately it is not about miserable cretinism or disgusting dishonesty on the part of those who provided such an act of savagery and those who justify and defend them. Or maybe it is. However, because of intellectual generosity towards such a lack of subtlety in the taxonomy of possible carnal stories, I present here another more elaborate hypothesis. Such a state of sexual illiteracy and condescension towards rape responds to a complex ideological framework of beliefs, prejudices, power relations and values in which we have been socializing for thousands of years. This is what Foucault called power-truth-knowledge relations, which legitimize this inhuman and abstruse regime that feminists, in the 1970s, identified with the name of “rape culture”. A culture that, even today, suffocates our daily life.

From a historical perspective, one of the most repeated arguments in the culture of rape is precisely trying to disguise the act of barbarism committed by the rapist by making it appear to be the result of a spoiled, innocent and sought seduction game between the abuser and the abused that simply got out of hand; that is to say, a dissolution of responsibility is carried out when proposing a collaborationist hypothesis in which the same illegitimate wish of the executioner is attributed to the victim. In this way, the rapist does not assume responsibility for his act and hides brutal behavior as desirable and reciprocal erotic conduct or a frivolous sexual encounter. This heteropatriarchal justification, which subjects the victim’s pain to the imaginary deformed desire of the rapist and, likewise, poses the suspicion of agency over the victim so that the abuser is safe from responsibility and guilt, is the one that is found in the sentence “she wanted it to happen”, “she was asking for it” or “she consented”.

Unfortunately, this connivance, condescension and tolerance towards rape is found in key figures of the Enlightenment and in some treaties of the Ancient Régime. Voltaire, Diderot, and even Rousseau, in some of their darkest statements —which should lead us to question the undoubted goodness and exalted character of the Enlightenment movement— came to suggest that rape was not an iniquity, since it —literally— did not exist. In the culture of rape, the sexual act between adult men and women is always spoiled, since a woman would always be in a position to defend herself or to resist if she did not want to have sex. With this, a perverse penal code as well as lax social morals are created, both decriminalizing the behavior of the rapists, exempting them from responsibility, and blaming the victim for what happened: if she was raped, it is because she necessarily —by her own will— agreed to have sex, then —following the petty logic of the culture of rape— you can always put up enough resistance [1].

Following this logic, from a terminological perspective the term “abduction” subsequently plays a determining role in the culture of rape and has been used frequently in history to refer to sexual abuse. The abduction of Europa, for example, as well as the rape of the daughters of Leucippus, the rape of the Sabine women, or the rape of Proserpina, the term “rape” being replaced by “abduction” in most latin countries [2], are persistent themes of Greco-Roman mythology. The association between kidnapping (abduction) and rape as equal terms has an ancient origin and provides a subtle and perverse connotation to the act of rape: this would not be a crime against women and, therefore, its evil would not have to do with the pain inflicted upon the victim. Therefore, rape would be understood as a mere act of theft against an owner. The rapist steals a body that belongs to a father or a husband and, with it, the violation is typified as an act of theft, as a crime against property rights and not violence against women.

Even in times when rape was heavily punished the reason behind this was not the abuse to which the victim had been subjected, but because rape “annihilated customs and defied the king.” Meaning that in the Ancient Régime, for example, violation was not deemed to be reprehensible for desecrating the integrity of the victim, nor was it understood as a violent crime, but rather as a sin of lust that undermined the integrity of good manners. Hence the attempt to identify it or to establish a causal relationship with libertinism, promiscuity and connivance towards sexual violence —that we still find today in that miserable delusion of orgiastic fantasy that is trying to hide a group rape [3].

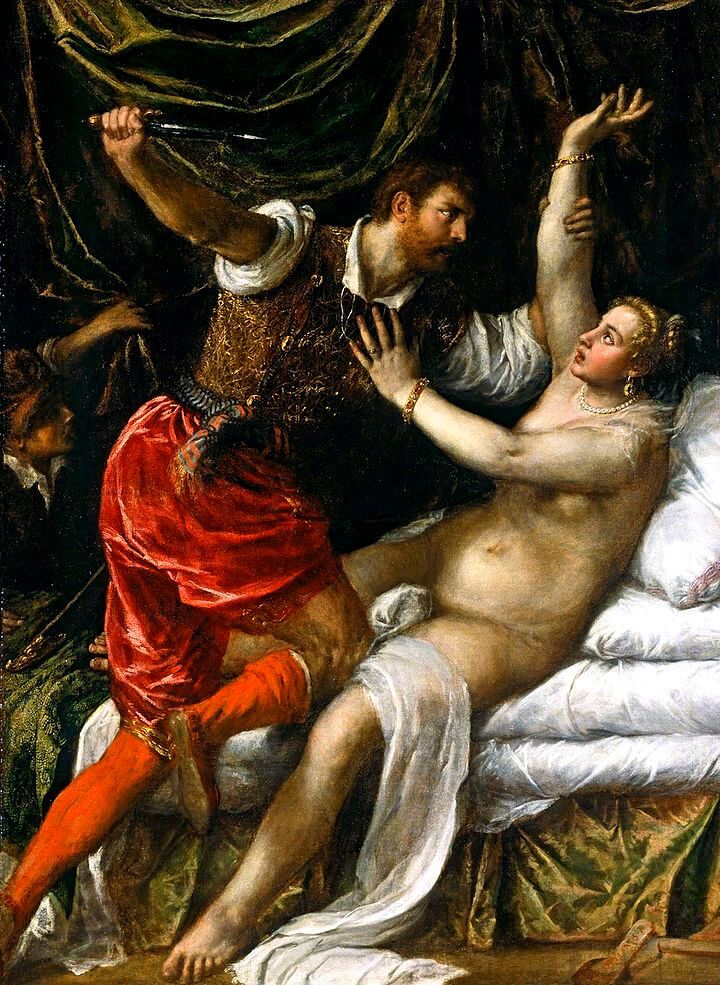

Moreover, in the history of rape we find a permanent aestheticization of sexual abuses, that is, an idealization of rape that helps to legitimize it. Rape constantly appears in classical mythology as an act that is not abominable but, on the contrary, begetting and heroic. In the metamorphosis of Ovid, a key story in the establishment of the Greco-Roman culture in which the vital events related to the gods are narrated, we can find a compendium of passages with multiple scenes of harassment and rape: Apollo and Daphne, the Rape of Proserpina or the myth of Pygmalion, for example. Similarly, Zeus, father of both gods and men in classical mythology, far from a model filiation, was a recidivist rapist without remorse: he violated Leda by becoming a swan and Europe after metamorphosing into a bull; he kidnapped young Ganymede; he abused his mother Rea and also his sister Demeter, a rape from which Persephone was born, who was also raped by Hades and Poseidon [4]. In short, our Greco-Roman cultural legacy, which supports the symbolism and traditions of the Western world, is absolutely disturbing and execrable.

If we take a look at the biblical legacy, although there is no creator god that forms the world through the violation of its feminine beings, there are various accounts in the Old Testament which are distressing and misogynistic. Among them is “The crime of Gibeah” (Judges, 19): a man offers his wife to be abused collectively, showing both the legality of a group rape and the social role of women as mere currency to be exchanged between men. In addition, the status of victim in such a reprehensible act is non-existent: the woman, contaminated after the rape and deemed guilty for it, ends up being dismembered by her husband. It goes as follows:

“As they were enjoying themselves, suddenly certain men of the city, perverted men, surrounded the house and beat on the door. They spoke to the master of the house, the old man, saying:

— Bring out the man who came to your house, that we may know him carnally!

But the man, the master of the house, went out to them and said to them:

— No, my brethren! I beg you, do not act so wickedly! Seeing this man has come into my house, do not commit this outrage. Look, here is my virgin daughter and the man’s concubine; let me bring them out now. Humble them, and do with them as you please; but to this man do not do such a vile thing!

But the men would not heed him. So the man took his concubine and brought her out to them. And they knew her and abused her all night until morning; and when the day began to break, they let her go.

Then the woman came as the day was dawning, and fell down at the door of the man’s house where her master was, till it was light.

When her master arose in the morning, and opened the doors of the house and went out to go his way, there was his concubine, fallen at the door of the house with her hands on the threshold. And he said to her:

— Get up and let us be going.

But there was no answer. So the man lifted her onto the donkey; and the man got up and went to his place.

When he entered his house he took a knife, laid hold of his concubine, and divided her into twelve pieces, limb by limb, and sent her throughout all the territory of Israel.

And so it was that all who saw it said:

— No such deed has been done or seen from the day that the children of Israel came up from the land of Egypt until this day. Consider it, confer, and speak up!”.

In chapter 13 of the Book of Daniel in the Old Testament we can also find the story of Susanna. This one moves around the concept of the spiritual cleanliness of a chaste woman as opposed to the legitimate violation of an impure woman, an idea that has survived to this day: a liberated woman or a woman who practices prostitution can not be violated because in the collective imagination she is always open, sexually accessible, available for coitus [5].

This biblical story tells us the drama to which the virginal Susanna is led. Susanna was married to a prominent Jew and —like Artemis in Greek mythology— is spied on while bathing. Two old judges find an excuse to justify their own perversion. They ambush her when she is alone to rape her while she is bathing naked. They give this woman two options: either she accepts being raped and the judges remain silent, or she resists and the judges, abusing their social prestige, publicly accuse Susanna of adultery. In the work by Guido Reni one can see the gesture made by one of the judges, putting his index finger to his mouth and pulling Susana’s cloak. The law of silence is one of the ideological fortifications that promotes the culture of rape. In a society where virginity and chastity outside marriage are encumbered and associated with a crime of lust against morality in the collective imagination of rape, and not as a violent crime against women, the victim of rape is “stained”, stigmatized, socially marked under the idea of a “fallen woman“. This is the reason why many choose to remain silent, not denouncing to avoid the shame of social brand.

In this biblical myth, Susanna, helpless and despite being in a dead end between rape or death, does not submit to the demands of the two judges. They publicly accuse Susanna of adultery, claiming to have seen how she was sleeping with a young man. She is condemned to death by stoning. However, in an unexpected twist of fate, the truth emerges thanks to the child and future prophet Daniel. Susanna is thus saved and the two elders are condemned to death.

The problem of resistance

Susanna’s myth has sustained one of the most damaging fictions for victims of rape: the idea that one can always avoid abuse and that one is automatically guilty if there was no resistance against the perpetrator(s) of the crime. If the victim was not able to refuse outright or did not physically fight until exhaustion to avoid the violation, it is considered that it did not take place as such, but rather that there was implicit consent —as is currently being discussed in the case of San Fermines when the victim remains “blocked” or in “state of shock”, unable to oppose the will of these five men.

Neither the clear numerical superiority nor the asymmetric situation of domination exercised by rapists that causes fear and inability for the victim to defend herself is taken into account. In the face of fear, one can even collaborate rather than oppose a resounding resistance — feeling a lack of protection that, furthermore, following the logic of guilt that persecutes the victim, weighs heavily on women who survive a rape. Heteropatriarchal culture teaches us not to defend ourselves, at the same time that it inculcates us that rape is an insurmountable stigma, a life sentence.

In her work King Kong Theory, Virginie Despentes speaks of her own rape, which took place when she was 17 years old. She gives an account of this devastating experience and dismantles the heteropatriarchal logic, which argues that if the victim did not oppose with vehemence it was because, deep down, she wanted to be raped. With her words, after which one can only remain silent, I finish this article in an austere bar without affectation.

“During the rape, I had a knife in the pocket of my red Teddy jacket, […] That night, the knife was hidden in my pocket and the only idea that came to my mind was: above everything, do not let them find it, do not let them decide to play with it. I did not even think about using it. From the moment I understood what was happening to us, I convinced myself that they were the strongest. A mental issue.

[…]

At that precise moment I felt a woman, a filthy woman, like I had never felt before and like I never felt again afterwards. I could not hurt a man to save my skin. I think I would have reacted the same way if there had been only one of them. […] Girls are domesticated to never harm men, and women are called to order every time they break that rule. Nobody likes to know to what extent one is a coward. No one wants to feel it in their own skin. I’m not mad at myself for not daring to kill one of them. I am furious against a society that has educated me without ever teaching me to beat a man if he opens my legs forcibly, while that same society has instilled in me the idea that rape is a horrible crime that I should not recover from. Above all it makes me angry that I still feel guilty today for not having had the courage to defend ourselves with a small knife against three men, a shotgun and being trapped in a forest from which we could not escape by merely running.

[…]

Men, frankly, ignore the extent to which the emasculation device of girls is unstoppable, so everything is scrupulously organized to ensure that they succeed without risking too much when attacking women. They innocently believe that their superiority is due to their great strength. They do not mind fighting a knife with a shotgun. They think, happy, imbeciles, that the fight is egalitarian. That is the secret of their peace of mind” [6].

*This article was originally published on La Grieta. It was translated from Spanish by Ángel Roldán.

Footnotes

[1] “[…]A rape attempted by a man alone on a determined woman would be impossible by mere physical principles; the feminine vigor suffices for the defense; the woman always has sufficient “means”. The jurists of the Ancient Régime consider it practically a fact. This is what certified in 1775 the “Traité de l’adultère”, by Fourneli: “No matter the superiority of a man’s forces over those of a woman, nature has endowed the latter with innumerable resources to prevent the triumph of her adversary”.

“The philosopher [Voltaire] specifies the physical arguments, describes the obstacle of the bodies and entertains himself detailing the movements:« To the girls and women who complain of having been raped, one should simply tell how a queen avoided in other times the accusation of a whistleblower. He took the sheath of a sword and, while moving it, showed the woman that it was not possible to put the sword in the scabbard. In this sense, rape is similar to impotence; there are some cases that should never go to court. “The physics of the bodies are considered sufficient to convince the judges. The argument of consent acquires a letter of nature, intuitive anatomy becomes a criterion of truth”.

Vigarello, Georges (1999), A History of Rape: Sexual Violence in France from the 16th to the 20th Century, Madrid, Cátedra, pp. 69-70.

[2] “Rapt” in French, “rapto” in Spanish, “ratto” in Italian.

[3] See Vigarello, Georges (1999), A History of Rape: Sexual Violence in France from the 16th to the 20th Century, Madrid, Cátedra, p. 29.

[4] See Koulianou-Manolopoulou, Panagiota/ Fernández Villanueva, Concepción, «Cultural stories and legal speeches about rape», Athenea Digital, number 14 (autumn 2008), 1-20.

[5] Regarding this matter, I recommend the movie Nuts with Barbara Streisand, to develop a different point of view on the links between prostitution and sexual abuse.

[6] Despentes, Virginie (2006), King Kong Theory,translation by Paul B. Preciado, España, Melusina, p. 41. (translation from the Spanish version by Ángel Roldán)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)