Two years ago in Berlin, Yanis Varoufakis launched the project DiEM25 (Democracy in Europe Movement 2025), a “democratic, pan-European and cross-border” political movement. DiEM25 intended to build a democratic Europe from an internationalist project in order to meet the various crises crisscrossing the continent (debt, banking, poverty, low investment and migration), and to tackle the disintegration of the union, the misanthropy and the rise of xenophobia and toxic nationalism.

Just one and a half years of existence, one of the members of its advisory committee renounced from his role. Last July, the Italian philosopher Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi presented his letter of resignation declaring: “We have trusted that Europe could overcome its history of violence, but now it’s time to acknowledge the truth: Europe is nothing but nationalism, colonialism, capitalism and fascism. (…) Nazism is the only political form that corresponds to the soul of the European people”. Bifo wrote this letter in response to the European Union’s actions in the face of the refugee crisis. “Auschwitz on the beach” he labelled it, comparing the refugee camps along the Mediterranean coasts with the concentration camps created by Nazism. From Bifo’s perspective, the reiteration of continental Europe’s history is cyclical – “five centuries of colonialism, capitalism and nationalism”, and this intransigence is therefore the symptom of a form of violence that has become structural and irreparable. The naturalization that the repetition brings has made the European soul violent in itself and, as consequence, a democratic project has become impracticable.

In recent years we have witnessed the resurgence of fascism in Europe with a new version of the old nationalist right. Those new variants have established a presence in parliaments, and in the political and social fabric of countries in the European territory. This is a situation that is undoubtedly increasing. The National Rally in France, Jobbik in Hungary, Golden Dawn in Greece, the Freedom Party in Austria, the Sweden Democrats, The Danish People’s Party, the League in Italy, the True Finns, the PVV in the Netherlands, AfD in Germany, Prawo i Sprawiedliwosc in Poland… Under such conditions it seems reasonable to think that this revival corresponds to that violence identified by Bifo as endemic, and originated in the core of the European being (as European essence).

A logic of survival

Just a few decades ago, in the mid-70s, Pier Paolo Pasolini came to a similar assessment in his Article “The Disappearance of the Fireflies” or “The Void of Power in Italy” (“La scomparsa delle lucciole” or “Il vuoto di potere”). His concern was related to the disappearance of the popular spirit. In this text Pasolini remembered an image from his youth in the fields surrounding the city of Rome, where the fireflies were a luminous community emitting signals to communicate with one other. At the time of writing, Pasolini pointed out how pollution had made them disappear during the previous decade. Likewise, the industrialization processes that occurred in the 70s in Italy were challenging the diversity of particular cultures, hence erasing all traces of humanity, community, or solidarity. Due to the mutation of capitalism the “community of fireflies” disappeared, and the same was happening with the capacity of the peoples to emit signals to communicate at night. The totalitarian power machine threatened the “anthropological vocation for survival” and the ability of political resistance with it.

In his book Survival of the Fireflies, Georges Didi-Huberman enters into dialogue with Pasolini’s judgment. He begins by recalling the relationship established by Dante in his Inferno: “In the core of hell, in the bolgia of the ‘evil counselors’, the little lights of evil souls fluttered, well away from the great and unique promised light in Paradise”. Yet this universe has been reversed, Didi-Huberman continues. Hell is now well lit and the “murky politicians” are overexposed under the glorious light of the ‘society of the spectacle’. Likewise, people’s souls have become small lights trying to escape from the threat. Small lights emitting minuscule glances in spite of all, like fireflies. In this new order of things culture “is no longer what protects us from barbarism”. The absolute light of hell has made its shinings imperceptible, and to finally become “the very medium in which new intelligent forms of barbarism thrive”. If culture is no longer in the hands of the people, what are people capable of? Has the capacity of political resistance survived, despite Pasolini giving it up as lost?

Ever the optimist, Didi-Huberman directs our gaze towards those flickers emitted by the fireflies, and in doing so he gives us a hopeful view to the future: a space within thought from which to confront despair. Fireflies have not disappeared; they just have moved to another place where we have not followed. Similarly, Pasolini just ceased to identify the signals between the peoples. In order to perceive those signals or glances a special gaze is necessary, a dialectic exchange of gaze and imagination, says Didi-Huberman recalling Benjamin. If we observe in an appropriate form, thought will find the way to reveal, expanding itself beyond its own limits. At that specific moment it is freed from the violence of social control and becomes able to generate a new imaginative reality. In other words, at that moment, images generate a break or change in the coded system of signs that determines our understanding of reality. This is the logic of survival: perhaps minute but unstoppable glances of the freedom of the spirit, that sometimes escapes our gaze.

Violence is plaguing European territory and its political imaginary, it is undeniable. The discourse of national identity – whose consequences Europe should still remember – has reappeared. Looking ahead, it is essential to reflect on fascism, and to determine whether it now has traces in the body or has become the body itself. For such an enterprise I propose to follow the logic of survival, avoiding falling prey to the closure of the imagination that brings defeatism: seeing the present as announcement of the horror about to come, and the future as continuation of the infamy of the present. Let us start with Bifo’s gesture of resignation, which a priori seems to be the consequence of such a closure.

Varoufakis answered Bifo through another letter: “You wrote a splendid and timely “J’ accuse” letter to Europeans as a true, unreconstructed, fed-up, European. And in so doing you offered Europe a small, tiny but important chance to save its soul.” Varoufakis found a beam of light: if Bifo (whose being is irretrievably European) expresses his contempt for that which Europe has become, it is because Europe is still capable of creating democratic thought. Therefore, there are still possibilities of being something “other” that do not originate in violence: of being people.

Last September Bifo wrote another letter on the future of DiEM25. He first proposed a necessary political action, to “prepare the unpredictable”: “to make visible what at present we are unable to see (…) beyond the apocalypse that dominates and obscures our vision.” To put it another way, to activate the dialectic gaze that – as previously said – is based on an exchange with the imagination.

Few foresaw (as to give an image to the unseen) what was happening inside the Nazi concentration camps. This was a reality without images. The regime made the effort to conceal the true objective of the camps by controlling photographic records. The population did not have enough referents to imagine (to form an image) of such barbarism. Now, the refugee camps in the Mediterranean are set to invisibilize its violence in the eyes of voters. They are opaque, and hardly any images have been published in the press. In our present times, the image is what determines the cognoscible. Therefore, events escaping our gaze are simply non-existent. But today we do have images of the ultimate expression of violence. History has warned us. From this approach, Bifo’s comparison takes another dimension. Bifo is not speaking from pessimism as Pasolini did, but through a performative use of words and actions. He is giving an image to the opaque presence of the Mediterranean camps, activating a space of our imagination to foresee what is hidden. He triggered a gleam and created resistance by doing so (or survival to continue with Didi-Huberman’ terms) helping us –Europe, to survive in spite of all.

Images from feminism, “gleams” for Europe

The obsessive defence of neoliberal policies by the European Union, and the ensuing crises have engendered mistrust among European citizens (so called Euroscepticism). In addition, the processes of deterritorialization implicit in these economic policies have broken the connection with our symbolic maps, affecting the very construction of identity. As a result, the European population has been left at the mercy of distress and necessity of re-entrenchment. A fertile ground for the return of fascism and nationalist discourse.

As in classic fascism, the new European far-right politics seeks protection of specific cultural differences and lifestyles based on the group of the nation, and articulated in xenophobic and racist rhetoric. They promise to repair the increasingly blatant precariousness of existence by appealing to mythical signs of belonging, rather than solving policies to the satisfaction of fundamental rights. A mere distraction. However, as noted by Boris Groys, there is an important difference between the classical fascist movements and this new nationalist right in Europe: while the former were aggressive and expansionist (seeking the establishment of a universal order), the new right is presented as an act of retreating: it is defensive and protectionist. The present disintegration of Europe has given space to xenophobic and racist arguments, and as a result immigration (the highest expression of which can be seen see every day on the Mediterranean shores) has become the focus of almost every political agenda.

The origin of the conflict, though, seems to be deeper. In Art Power, Groys noted how what have traditionally been associated with European values (respect for human rights, democracy, tolerance with the other, and openness to other cultures) are actually universal values. This implies a paradox at the very core of the European being: Europe, understood as the sole guarantor of these values can be defined only by denying the legitimate possession of them to all other cultures. It therefore seems a logical conclusion to infer that a democratic Europe cannot exist within a European project that is still defining itself in such a way. If we seek a democratic future, it is urgent to re-formulate European being with respect to the world, and to leave behind the Eurocentric understanding of the “distribution of the sensible”, to use Rancieran vocabulary.

In spite of all, then, let us search for a place from which to define European subjectivity anew. One which reconciles being one and being in the world in an ecological way with all cultures, and which articulates diversity through a common project. It is time to remember that the tradition of European political thought has not only produced liberalism and nationalism. Let us, then, recover an internationalist understanding of being. Following the logic of survival, it is certain that the solidarity in which socialist thought is based has survived, and is flickering somewhere.

For the future of Europe, the objective will then be a cross-border project, independent of the economic and identity restraints that the current systems of governance are proposing. Today, no project from the left seems to be able to capitalize on the discontent in the form of projects for a future. Therefore, it is necessary to find alternatives in other forms of language able to break from the Manichean opposition between the right and the left. Perhaps we could find in Feminism a glimpse of our starting point.

The women’s revolution is the historical struggle to overthrow the patriarchal regime through the defence of a radical democracy. Its dimension and objectives make feminism something that affects everybody, penetrating through every condition that determines our identities (whether these are related to class, ethnicity, gender, etc.) It is then, by definition, a cross-border movement affecting the world’s population as a whole. Solidarity itself put to work in order to achieve an unconditional universal empathy.

At present, feminism is a place from which to create a community that constantly disbands the creation of otherness. Its power lies in the re-articulation of our languages and our reality by creating images of previously invisible realities within capitalist and patriarchal societies (for example, by making gender violence, figures of assault, or murder visible). These images are composing new dialectics from which new ways of being can be proposed and therefore, from which a Europe beyond Europe can be thought.

Of course this is a path with detours. In recent years we have seen how feminism has gone from culturally marginal zones to become part of the overall information system, allowing more and more people to identify with it. However, this wider dissemination has also brought the appropriation of the term by the capitalist logic of the sphere of information, making feminism serve radically antagonistic ideological projects.

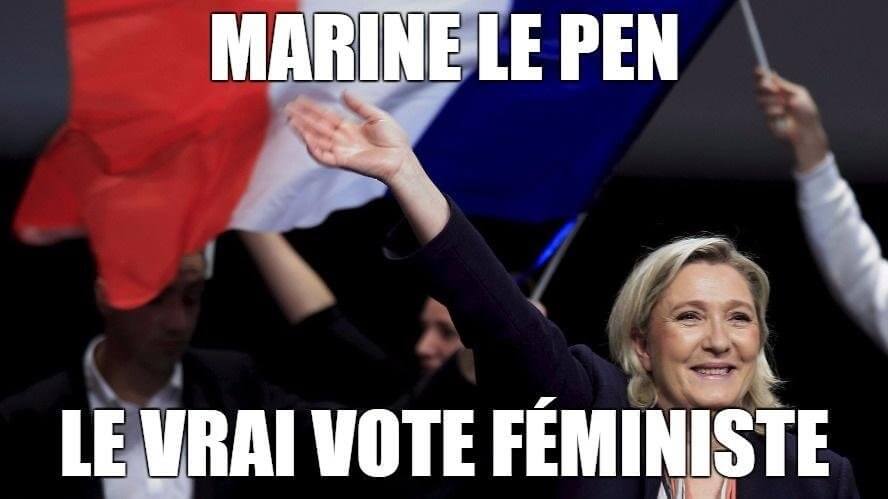

Thus we find supposedly feminist discourses within the various European nationalist right-wing parties and the neo-liberal political programs, distorting the content of the word itself while adapting it to their consumers. In both cases the struggle is under threat of depoliticization. That is to say that those discourses are giving images to feminism –and meanings with them, that do not belong to it. A feminist future cannot happen under totalitarian speeches based on racism and xenophobia, or by the promotion of difference that drives economic neoliberalism, which puts the differences in the service of capitalist economic exploitation. In both cases feminism would fall into a contradiction, becoming something monstrous.

Looking ahead to confront the paradox of Europe and to thinking of new ways of being through feminism, we have to be aware of the risks implicit in this rapture. The meaning of feminism may one day no longer be so clear. If that day comes we must remember that the strength of solidarity does not disappear, it just has moved to another place. We have to avoid falling into the pessimism that ravaged Pasolini’s spirit and like Bifo, look for images or gleams from whence to recover solidarity.

*This article was first published in Spanish on La Grieta. It was translated by the author.

** Lead image: part of the project #DocumentaSceptic by Thierry Geoffroy, set up during the art festival to question the event itself.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)