The battle over the criminalisation of abortion is revealing of the overall political scenario in Brazil. Criminalising and controlling issues of gender and sexuality is the moral foundation of a growing right-wing ideology that is driving the country’s political development. Now, with a political system weakened by corruption and collusion, the battle for abortion is playing out on the internet through individuals, movements, and even web robots (also known as ‘bots’).

In Brazil today, political institutions have been weakened to their most vulnerable since the military dictatorship ended 30 years ago. Women make up less than 10% of elected representatives, placing Brazil amongst the worst in the world for gender equality in politics.

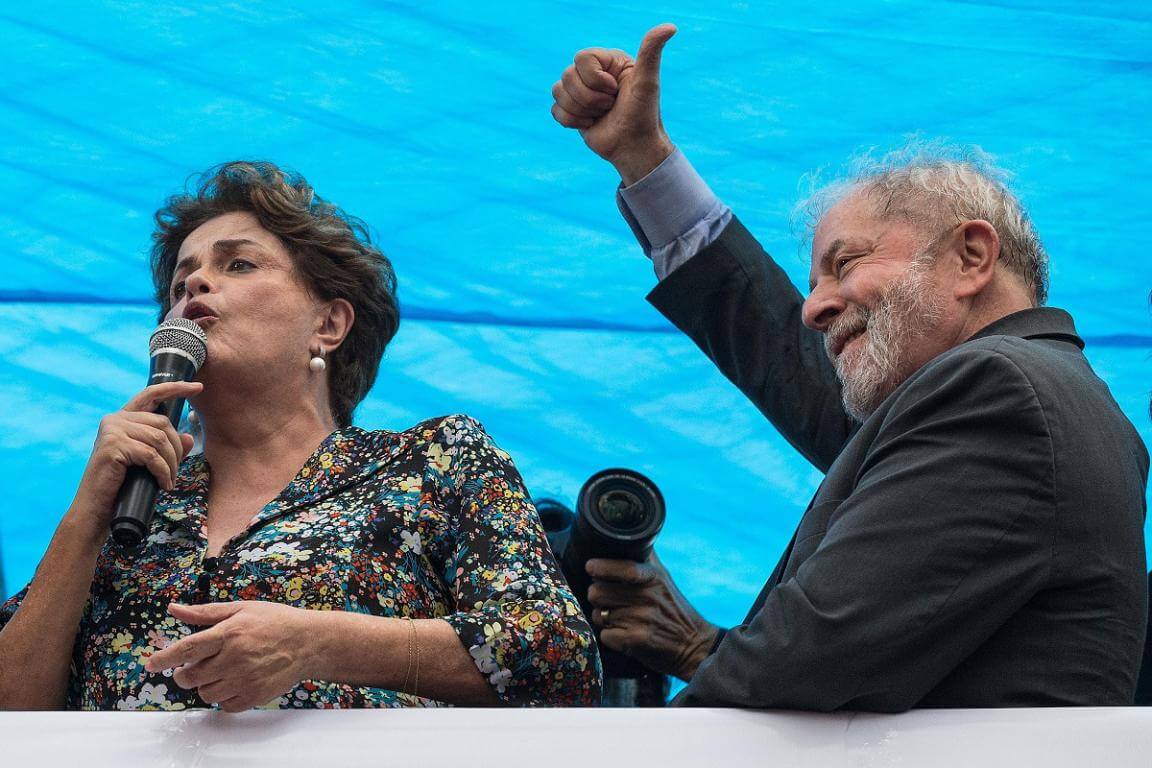

The country’s first and only female president, Dilma Rousseff, was deposed by a 2016 political coup which showed the system’s pervasive and severe sexism. Her predecessor, and the frontrunner for October 2018’s presidential elections, Luiz (Lula) Inácio Da Silva, is currently on trial for corruption. Almost 46% of the population believe that this is an unfair trial by the media and judiciary.

At the same time, targeted gender-based violence is rising. Marielle Franco, a black, lesbian city councilwoman from a favela in Rio de Janeiro, was assassinated on 14 March. Her murder has caused outrage in Brazil and beyond. Her openly feminist, black and favela-centered politics were a source of hope for marginalised groups in Rio de Janeiro, currently governed by a conservative city government and an evangelical mayor.

Lack of access to information plays a big role in the weakness of democracy in Brazil. Eleven families control mainstream channels of communication. Civil society organisations point to insufficient information on human rights and basic political mechanisms, especially for the most marginalised groups and communities. The majority of people receive their information from television, which is dominated by O Globo, widely seen as biased, particularly in its coverage of Rousseff’s trial and impeachment.

Lack of access to information plays a big role in the weakness of democracy in Brazil.

The internet has become a main battleground for information and civic dialogue on politics. Brazil is the largest user of social media in the world after the United States. Lengthy, passionate, even violent discussions about politics on Facebook, Twitter and Whatsapp are not uncommon. In this little understood but widely-used new frontier, citizens are staking political claims amid a general perception of the uselessness of formal political participation.

Online hate speech and gender-based violence are on the rise. ‘Trolling’ – systematically attacking individuals or ideas on the internet – has increased. A 2016 study showed that 84% of comments on social media platforms that addressed politics, women, race and LGBTQ people were negative. Of nearly 50,000 comments related to gender inequality, 88% showed intolerance.

Movimento Brasil Livre (MBL – Movement for a Free Brazil) is one of the most prominent right-wing movements to have emerged. It has organised enormous protests, events, and campaigns for Rousseff’s impeachment, ahead of and during her trial, as well as for a “corruption-free” Brazil.

MBL has made feminism an enemy of their public, labelling it ‘hate speech’ and publishing posts on Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube attacking feminist analyses, such as those on gender wage gaps, as ‘myths.’

A number of fake profiles and bots have been set up to spread hateful messages. This has led to consistent condemnations and removals of feminist Facebook pages, Instagram handles, and profiles.

This backlash is not restricted to Brazilian public figures; when Judith Butler, a well-known and well-regarded scholar on sexuality issues, and author of the term ‘queer,’ arrived in Brazil last year to speak at a conference, she was harassed and almost physically attacked by right-wing Brazilians.

As in other parts of the world, for at least the last decade, an increasingly successful right-wing tactic in Brazilian politics has been to mobilise people around patriarchal, heteronormative ideas of the family, and to refer to gender as ‘gender ideology’. This is a longer-term, more insidious strategy than simply waging war directly on feminist movements.

Right-wing tactic in Brazilian politics has been to mobilise people around patriarchal, heteronormative ideas of the family.

Arguing that ‘gender ideology’ is false and damaging, politicians have explicitly prohibited the word ‘gender’ to even appear in school curriculums.

‘Escola Sem Partida’ (School Without Party), a self-described “educational freedom movement,” works to prevent any mention of gender and sexuality in schools. While homosexual marriage is legal in Brazil, a recently-passed Statute of the Family defines the ‘family’ exclusively as the union of a heterosexual man, woman, and their children.

A united ‘Evangelical Front’ of fundamentalist politicians strategically attacks liberty of gender and sexual expression. Outside of organised politics, this has also impacted the realm of arts and culture. An exhibit called ‘Queermuseu’ was attacked and shut down in São Paulo in 2017 amid conservative protests and accusations of pedophilia. It was curated by and featured queer artists who openly talked about bodies, pleasure, and sexuality.

Meanwhile, over the past three years, feminist movements have come out of the political sidelines in leftist social movements and gained new force and energy.

The ‘Feminist Spring’ of November-December 2015 accused Eduardo Cunha, then head of Brazil’s lower house of Congress, of authoring and pushing forward a draft law that would criminalise abortion in cases of rape. It would make emergency contraception illegal, and even prohibit doctors from informing their patients that abortion is a legal option in Brazil in certain situations.

Feminist movements mobilised hundreds of thousands of Brazilians to storm the streets in dozens of cities. The draft law was tossed out, and continued feminist-led protests against Cunha throughout 2016 contributed to popular pressure against him, leading to his own trial and expulsion from political office.

Feminist movements have come out of the political sidelines in leftist social movements.

Cunha’s intentions are still alive and well in his political allies, however. They form a majority in Congress and have since authored far worse laws, programs, and constitutional amendments.

PEC 181 is a current example. This proposed constitutional amendment was originally drafted to provide additional maternity leave and support for women who give birth prematurely, but it also potentially criminalises abortion in any and all circumstances, with a clause that states: “Life begins at conception.”

Although feminist movements have worked to spread knowledge about this ‘hidden clause,’ including through popular mobilisations in more than 20 cities, journal articles and online activism, PEC 181 remains on the table. Known to some as the ‘Trojan horse bill’ for its widespread appeal even to Brazilians who are sympathetic to women’s rights, its hidden clause could undo the little progress that has been made on reproductive rights in Brazil.

Voting on the amendment has been repeatedly suspended for the past three years, as a result of protests. On 22 March, a special commission in the lower house of Congress voted once again to suspend voting on the amendment, though it has not been definitively shelved despite federal deputies pointing out that the contentious clause directly violates the country’s constitution.

National media outlets have barely covered PEC 181, protests to the proposed amendment, and its potential repercussions.

PEC 181 could undo the little progress that has been made on reproductive rights in Brazil.

A number of other bills and proposed constitutional amendments threatening women’s sexual and reproductive rights have also been in the works in Congress. The National Front for the Legalisation of Abortion (Frente Nacional Pela Legalização do Aborto) launched a call to action about these attacks in August 2017, which more than 90 feminist groups across Brazil signed and shared in their networks.

Around the same time, young feminists organised the first edition of Virada Feminista, a 24-hour online event featuring live-streamed discussions by feminists to challenge stigma around abortion and spread facts and information.Virada Feminista has since grown into a significant movement, coordinated by Jéssica Ipolito and Thaís Campolino, highlighting online activism that visibilises different feminist issues, particularly sexual and reproductive rights.

Perhaps the most creative and innovative response to PEC 181 and other recent threats to women’s reproductive rights is Beta – a feminist robot on Facebook created by the Nossas national network of citizens’ rights organisations.

Before Beta was even formally launched, she organically accumulated 10,000 likes through word of mouth and peer recommendations. Beta works through the Facebook inbox function, and informs those who agree to receive her updates of different legislative or policy drafts that can threaten women’s rights.

“Beta was important when PEC 181 became a political issue on the table, exactly because she is capable of rapidly and practically mobilising women across Brazil: either through chatting with them or alerting them with notifications,” said Laura Molinari, advocacy coordinator at Nossas.

“Women were notified that PEC 181 would be voted upon and that they needed to get into action. Since they didn’t need to leave their Facebook inboxes in order to directly send emails to authorities pressuring them to vote against PEC 181, engagement was very high,” Molinari added.

Beta will make sure that Brazilians have access to information about how this and other bills that threaten women’s rights progress through Congress.

Presidential elections are expected in October 2018. The left’s frontrunner da Silva may, or may not, make it past the primaries – depending on whether he can stay out of jail. Even Brazil’s supreme court is affected by political collusion; every member voted for da Silva’s condemnation, though there is a strong argument that the evidence presented against him was insufficient.

2018 may be the year where the internet is more important than ever before for elections in Brazil, just as 2016 was for the United States, not least because this will be the first time in Brazil’s history when sponsored advertisements by presidential candidates on the internet are allowed.

2018 may be the year where the internet is more important than ever before for elections in Brazil.

In order to combat the stacked odds against them, feminist movements will have to continue to be creative about the ways in which they communicate and use the internet.

Digital tools for mobilisation are crucial, but offline tactics and strategies are still necessary and effective, as seen by the latest developments in Argentina that have initiated political dialogue around the legalisation of abortion despite that country’s right-wing and staunchly anti-abortion president.

Feminist movements and allies will need to actively address gender-based violence and ‘gender ideology’ believers who spread sensationalism, fake news, and hate online, as did supporters of Marielle Franco, who successfully denounced ‘Cetismo Político,’ a right-wing site that spread false stories about Franco after she was murdered.

Lawyers in Brazil have also organised online, asking those who see hate speech, fake information and calumnious statements about Franco to take screenshots that could be used to press charges against the culprits.

Clearly, ideological battles no longer play out only at election booths, but also over the internet. This will shape our future – both in the immediate and in the long-term.

***

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)