To be alive is to be privy to the flux and malleability of experience, identity and being, sometimes to be cast adrift in a great sea of anonymity and homelessness, even if your home as such comes with a very nicely delineated address found on a clearly labelled map.

There is something that remains nebulous about the idea of nationality, nebulous and arbitrary because I know or sense deep down that we are all cast adrift sometimes on that vast sea, not knowing really what our destinations are or even indeed the nature of our voyages. That is also why I am so resistant to all forms of nationalism and the cheap distortions that all too often accompany it. I believe that people and life is a much more complex, ambiguous and rich thing than a passport’s bureaucratic procedures of identification would have us believe. I, for instance, describe myself as Anglo-Armenian. And yet even that dual nationality remains for me a recalcitrant, inadequate thing. Perhaps nationality is like a clearly labelled bottle, whose contents nonetheless remain unidentifiable when opened.

Of course we all need passports and we all need homes, but for the creative writer the grey areas, the out of focus borders that themselves stand on the periphery of vision give sustenance, meat, meaning to a creative writer’s work and, when distilled into art, give rise – sometimes, if you are lucky – to the haloed territory of universality. It is precisely by mining and exploring those experiences which have no specific cultural or nationalistic stamp that a writer can achieve universality – a writer’s work can withstand translation, can become truly global because it articulates experiences that have nothing to do with a specific geographical region or trend or set of values. Samuel Beckett’s fiction, for example, truly came into its own when he started writing in French, and his mastery of both English and French facilitated his formation as a writer with a truly original vision and voice.

In my own writing I’ve often come across the problem of setting – where should I set a particular story? This often seems to me to be an insurmountable problem because to set a story somewhere must entail – in some way – limiting that story’s particular potential for universality. To set a story in a ghetto in Naples is very different to setting a story in London’s Fortnum and Mason’s. This might seem self-evident, but such extremely opposed contexts clearly dictate very different lines of behaviour for the people found within them – altering appearance, dress, speech, even thought.

When I was writing my novel The Fabrications I had originally flirted with the idea of setting the book in a completely anonymous city – because I thought anonymity was the best frame in which to evoke the kind of quasi-allegorical ideas that I wanted to play with. But then I realised the reader wouldn’t buy it (the concept, not the book!), especially since the novel was beginning to assume the dimensions of a long book. So I ended up setting it in London, the city in which I was born and bred but perhaps the city in which I have always felt least at home. The London of The Fabrications is, however, altered, adapted, transformed because I wanted it to be London and not London at the same time, to retain the capacity for suggesting any great metropolis, with all of its pleasures, decadence, corruption, any old cityscape providing the backdrop against which the characters’ lives play out.

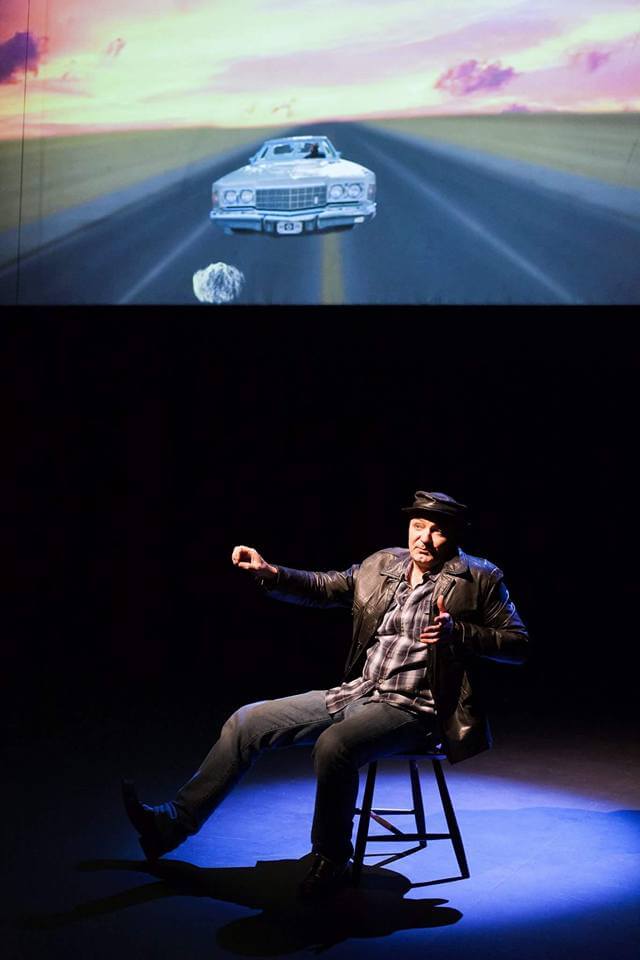

Three years ago I received a commission to write an erotic story by an Italian editor, Gabriella Montanori, and what came out of that was The Pain Tapestry, which I subsequently adapted into a monologue for the stage and directed myself in the impeccable Italian translation of Andrea Sirotti, with the brilliant Italian-American actor Roberto Zibetti at the helm, first in Florence and then in Turin. The show subsequently moved northwards, very northwards, to Iceland and I recently had the immense pleasure of seeing the monologue performed staged in English in Reykjavik. Pall Palsson, the Icelandic actor, delivered a virtuoso performance of chameleon-like versatility, in a magical, multi-media production directed by Runar Gudbrandsson. There was something almost intoxicating about all the diversity of nationalities and contexts coming together in this artistic project, clashing and resolving into a beautiful quiescence of free collaboration.

The Pain Tapestry takes place in America’s Mojave desert. Why did I choose to set it in such an iconically barren landscape? That again, I think, is attributable to my sense of discomfort with fixed, culturally specific places. I was greatly attracted to the desert because it seems to me to offer the perfect setting for dramas that are interested primarily in things that have nothing to do with cosmetic or topical issues and dilemmas. The desert is a void – albeit in the case of the Mojave a quasi-mystical and hallucinatory one – but a void was very attractive to me because it jettisons so much of the detritus and trivia of contemporary society. The desert give me a head start in my exploration of the territory of timeless human tropes, emotions and predicaments: the search for love and companionship, the mythical aspects of literature, violence as revenge, as punishment, self-destruction as a path towards redemption and purgation, which are some of the ideas The Pain Tapestry deals with.

And what does my obsession with anonymity, with places that are not places, with cities that are other cities, mean in the final count? It means writing across borders, relinquishing cultures and meanings that are strictly tied to nations and finding those that lie beyond them and eclipse parochiality with their deeper truths. Writing across borders, across places is the kind of writing that appeals to me precisely because it taps into that reservoir of universality that makes people feel connected, that makes us able to understand and appreciate one another, as opposed to retreating into labels, defensive or aggressive postures, jingoism or the imperialism of empires like that of present day America. And maybe writing and art’s brightly blazing torch might lead us into a new realm of comprehension, tolerance and openness I sometimes naively believe, but always fervently argue for.

*Baret’s novel The Fabrications is published by Pleasure Boat Studio and is available to purchase here.

**The Pain Tapestry will have a new run in Reyjkavik soon, dates to be announced. Please consult the Facebook page for further details.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)