Year 2018 will remain written in history. Sure, there are many reasons for this. Many of them with a bitter taste, some with a smile, and rare ones full of pride. There are moments in which we tend to release tears without hesitation, with a weird mixture of anger and relief. It seems to me that every feminist in her lifetime needs to experience this moment. There were at least two moments like this in 2018, when many of us recall having shed those tears. After all, in recent years there has been a rallying cry for the feminist resistance. Just think about the general strike. Under the slogan “If we stop, the world stops,” many events all around the world on March 8 were shaped by the development of the #MeToo movement. But two events in particular filled us with pride and anger.

“I will be travelling 5,169 miles from LA to Dublin and will be thinking of every Irish woman who has had to travel to access healthcare that should be available in her own country,” says one of many women on Twitter. Our feminist hearts were bursting, and no one should be ashamed to say that. Many of us cried while reading #RepealThe8th threads on our screens. Some were calling it “the most important referendum we may every face”. And it was a victory: on 25 May 2018 by a margin of 66.4% yes against 33.6% no and on a record turnout of 64.51%, Ireland voted to repeal the Eighth Amendment of its Constitution. Irish citizens were travelling from all over the world just in order to vote. Since 1983, abortion in Ireland had been strictly prohibited. The Campaign to Repeal the Eighth Amendment has its roots in the unsuccessful Anti-Amendment Campaign of 1983. In 1992, three abortion referendums followed the campaign, and then campaigning slept for more than 20 years, until the death of Savita Halappanavar in 2012, although it is illusory to think that feminists in Ireland were actually sleeping for all those years.

Reactions came from all over the world, media from the UK to Argentina were reacting to the results. Despite the fact that the campaign was all but fair, as later revealed by Open Democracy, this victory lit a fire in pro-choice movements around the world.

Less than a month after, the focus was on Argentina. Encouraged by the recent events in Ireland, activists started to take to the streets in Argentina calling on their Congress “to bring them one step closer to having safe and legal abortion.” While Europe was enjoying the summer season, in Argentina it was freezing cold. Yet, women, girls and their supporters continued to camp outside the chamber of deputies, where debate lasted long into the night, hoping for a bill that would allow for abortion up to 14 weeks. “The World Is Looking At You”, they were saying. It felt like one step closer, #AbortoLegalYa. On the morning of June 14, the bill narrowly passed in the lower house of Congress.

But on August 8 the Argentine Senate, by a narrow margin, voted against the Law of Voluntary Pregnancy Interruption (IVE), the law which would have finally legalized abortion in Argentina. The proposed legislation, which would have allowed women to seek an abortion within the first 14 weeks of pregnancy, was supported by 31 lawmakers, rejected by 38, with two abstentions. In a country where abortion is currently allowed only in the event of rape or when a woman’s health is at risk, the importance of this law is unimaginable. Moreover, in that moment Argentina served as a role model for the rest of Latin America.

Currently, only Cuba, Uruguay and Mexico City have legalised abortion. Just a few days before the vote in Argentina, three women were stabbed in Chile while “protesting in favour of free, safe and legal abortion”. Previously, Chile had one of the most restrictive abortion law in the whole world, but in August 2017, during the presidency of the former Chilean president Michelle Bachelet, the new bill passed, which now allows the termination of a pregnancy in three cases – when a woman’s life is in danger, when the foetus will not survive the pregnancy, or in cases of rape.

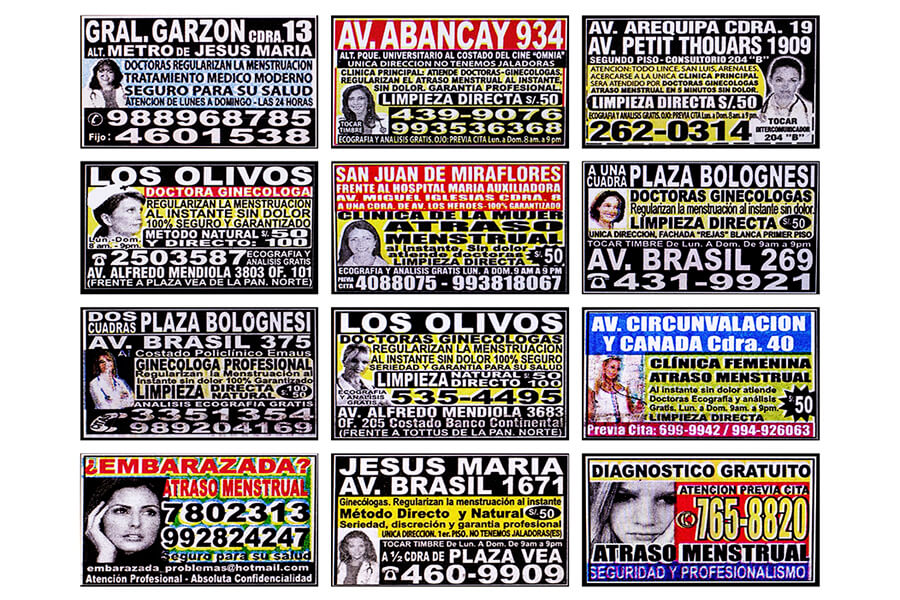

Abortions in Latin America have a history of being unsafe and illegal (especially for poor women) but the groups fighting for legal abortion across the region constantly face a strong resistance from the Catholic Church. So while the Catholic Church keeps fighting women, in Latin America abortion policies have led to the needless deaths of thousands of women. According to Argentina’s National Ministry of Health, approximately 500,000 illegal abortions are performed in the country each year, many of which result in dangerous complications and death. In 2015, grassroots feminist movement “Ni Una Menos” (meaning “Not One Less”) protested the murder of fourteen-year-old Chiara Páez, but then continued to initiate calls for abortion-law reform to raise awareness about the number of women who have died as a result of illegal abortions in Argentina. It is important to note that the movement which started as a struggle against femicide, rapidly radicalized: the meaning of “violence” was expanded to capitalism and its impact on the lives of poor and working women as well as to gender non-conforming people.

In an interview with Cinzia Arruzza and Tithi Bhattacharya for Jacobin, five feminists and activists from Argentina – Luci Cavallero, Verónica Gago, Paula Varela, Camila Barón and Gabriela Mitidieri – explain how feminist movement in Argentina have shaped anti-capitalist feminism, hoping to see a similar trend set in everywhere else. Despite failed legalisation of abortion in Argentina, this process points to “the vehicles of ‘real power’: the bourgeois politicians”. For them, the real power of the resistance is lying in a general strike. “What would have happened if the ‘green tide’ had invaded the unions and on August 8 in Argentina, transport, schools, hospitals, factories, state agencies had paralysed the country?” they are asking. Feminism is not just an academic debate, which is why the concept of a “feminism for the 99 percent” is such an important point: “the violence against our bodies is not just physical violence. The violence is in the wage gap, in the unpaid labour that falls on our shoulders, in the debt, in the disciplining of our sexualities, in mandatory maternity, in unemployment, and our precarious access to basic services.” Less than a week after the Argentine Senate rejected a ground-breaking bill, media reported on the death of woman caused by an at-home abortion. This simply cannot be labelled as a tragedy, not in a country where around 500.000 illegal abortions are performed every year.

Yes, we do lose some battles, but while the decision on abortion in Ireland was in the hands of its citizens, decision in Argentina was in the hands of the powerful, the lawmakers. The Catholic Church played its role, accordingly. But there is something about those tears that we have all seen on women’s faces in Argentina, and we somehow know that everything has changed. For anyone who thinks that this anger can be overcome and forgotten, one thing should be clear: women in Latin America have simply waited for this moment for too long.

***

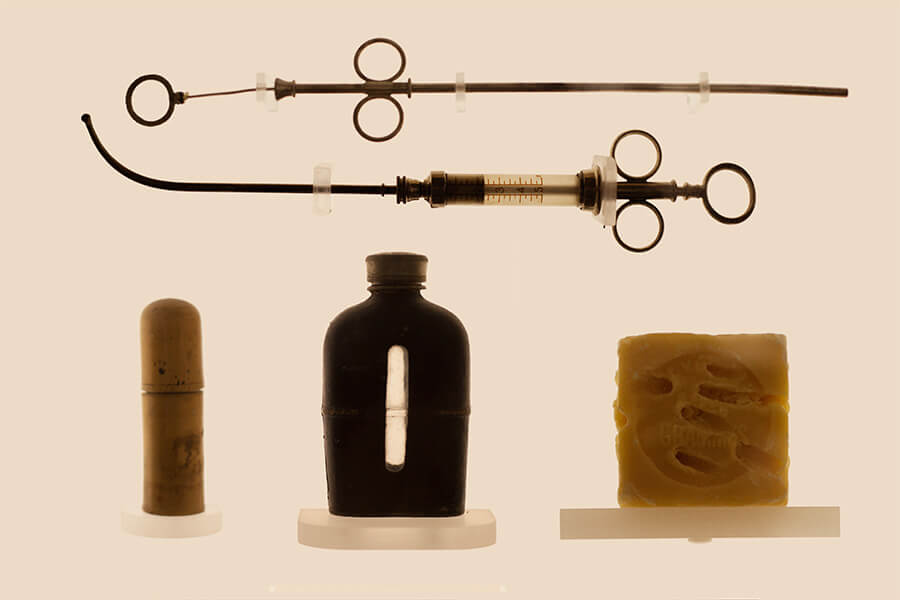

Laia Abril is a multidisciplinary artist working with photography, text, video and sound. Laia Abril’s new long-term project A History of Misogyny is a visual research undertaken through historical and contemporary comparisons. The on-going first chapter: On Abortion; was first presented at Les Rencontres d’Arles(2016). The book, published by Dewi Lewis can be purchased here.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)