Austerity measures have more effect on women: primarily because of cuts in the public sector where women are disproportionately employed, and on which, in terms of social protection, they particularly rely on. This is the baseline of the series of reports “Austerity, Gender Inequality and Feminism After the Crisis” commissioned and published by Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung. The reports include case-studies from nine countries: Russia, Spain, Croatia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Greece, Germany, Ireland and Poland.

Apart from valuable insights into the specificities of each country, this research series also offers materials and opportunity to identify prevalent issues regarding the current deterioration of women’s working and living conditions. There are also concrete ideas that could be used in the international feminist struggle.

“Austerity has a disproportionately negative short- and long-term influence on women,” says Oksana Dutchak, Deputy Director of the Centre for Social and Labour Research in Kiev and the author of the Ukrainian report. “This in itself can be a powerful message to the feminist struggle,” she adds. Dutchak is concerned about the fact that the current system has a particularly negative influence on some groups of women: the most underprivileged ones. Another issue is unpaid reproductive labour – many times proven as being at the core of the gender inequality problem in capitalism in general, and in neoliberal capitalism in particular. Oksana acknowledges its political potential: “this is how feminist struggle can be mobilized both internally and on an international level: around the demands for reproductive infrastructure and support/payment for reproductive labour,” she says.

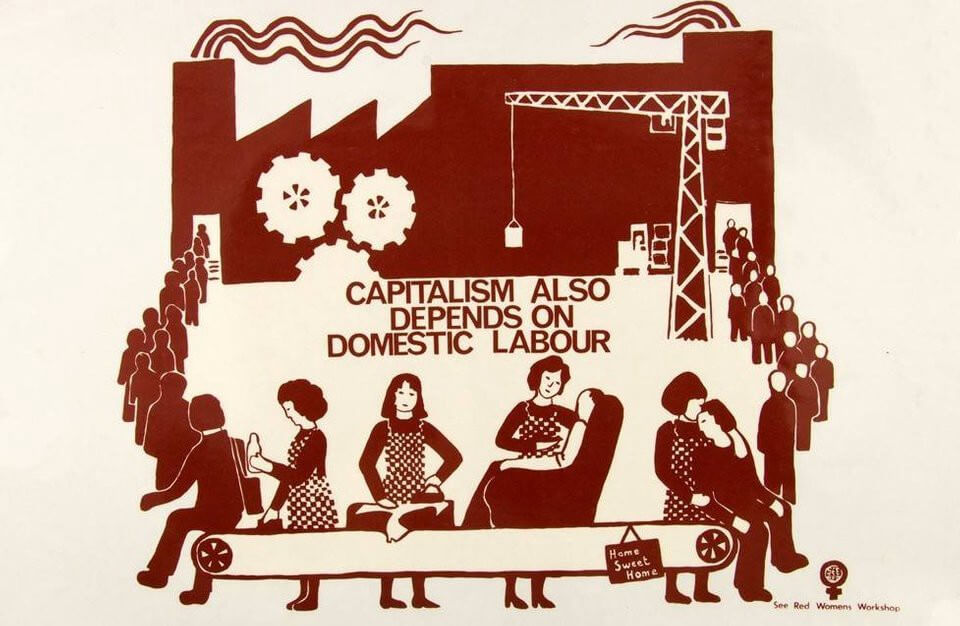

Another issue is unpaid reproductive labour – many times proven as being at the core of the gender inequality problem in capitalism in general, and in neoliberal capitalism in particular.

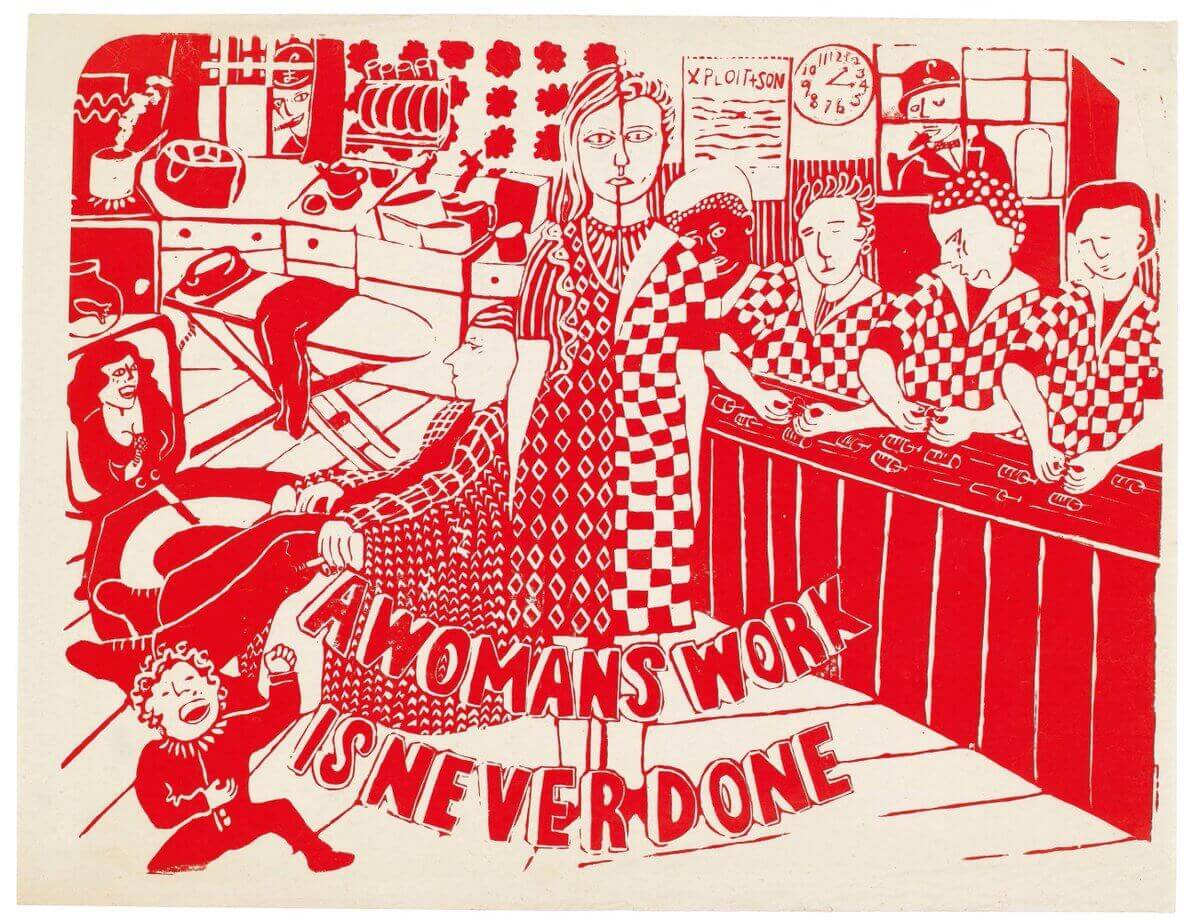

In times of crisis, the tendency of neoliberal economic policies towards the commodification of care becomes more apparent. The problem of social reproduction emerges as a key one. Speaking of the most visible socioeconomic consequences in Ukraine of the post-2014 “anti-crisis” policies, Dutchak singles out a few issues. “The most evident effect was, first of all, the relative devaluation of female “productive” labour – an increase in the gender pay gap both due to the crisis itself and to austerity measures. This devaluation also points to the fact that it’s women whose payment for “productive” labour mostly depends on the legal minimum wage (which was frozen when the crisis started), because it’s mostly women who work in lower-paid sectors and on lower-paid positions”, she says and points out that there can be hardly any effective feminist struggle “without a general socio-economic struggle: for better wages, for a living wage”.

The second consequence was a significant decrease in support, pay and subsidies for reproductive labour. The third important “retreat” of the state were cuts in reproductive infrastructure – kindergartens, other educational institutions, healthcare institutions etc.

“Throughout Europe, we are confronted with a situation that can be described as a crisis of care. Austerity policies particularly focus on the infrastructure that is necessary for the care of oneself and others: in the health sector, in care, in education and upbringing”, says Alex Wischnewski, author of “Who profits from the crisis? The impact of neoliberal state restructuring and the political shift to the right on women’s lives in Germany”.

“This affects women twice or even three times. On the one hand, they are the ones more active in those fields, and on the other, they absorb the consequences of the welfare state’s withdrawal into their families”, she adds. Paradoxically, Alex Wischnewski says that Germany is often considered to have been one of the winners of the financial crisis. “It is true that Germany’s economy was back on track in no time after the outbreak of the crisis. One reason for that is an export surplus that depends on the demand of consumers and markets in other countries. Still, the crisis was used to implement austerity measures that deepened a decade-long development of neoliberal restructuring and resulted in growing social inequality that has taken on a distinctly gendered dimension.”

Austerity policies particularly focus on the infrastructure that is necessary for the care of oneself and others: in the health sector, in care, in education and upbringing.

Since capitalism largely depends on free reproductive labour, it also often seeks ideological support in conservative, nationalistic and patriarchal principles. That’s why one can notice the connection between the effects of neoliberal economic policies and the process of repatriarchalization that, under certain conditions, follows in their wake.

“In some countries this has happened at the same time as an increased focus on traditional family models and further restrictions of abortion rights. Therefore, I think that the questions of gendered division of labour, social infrastructure and the questioning of (re-surfaced) gender norms could be closely related,” says Wischnewski.

Aliki Kosyfologou is the author of the report from Greece – a country that, according to her, is unique in that it has been treated as a field of experimentation for the austerity paradigm. She claims that austerity policies have had a disciplinary effect on the overall character of the European society. “The dismantling of the welfare state, new ways of regulating labour, the abolition of the right for collective bargaining, flexibility and flexicurity, unemployment and youth unemployment are some of the main aspects of the current situation in countries affected by the austerity agenda,” she says.

In Greece, nine years of austerity reforms have left nothing but collective frustration, fatigue and social disappointment. For example, Greek youth still struggles with high unemployment (39,8%) while other social groups cannot afford a decent living. Moreover, women, young people and migrants face structural discrimination due to the patriarchy, racial and generational inequalities. “In my opinion, the most important challenges of the international struggle against austerity and its social impact are those against authoritarian neoliberal policies, structural gender and racial inequalities and against the EU’s anti-migration agenda,” concludes Kosyfologou.

Inés Campillo Poza, the author of the report on Spain, thinks that even if the national contexts are very different, the European Union gives most of us an opportunity for cooperation around some common problems. “Germany, Ireland, Greece Spain, Croatia, they are all subjected to the same economic EU prescriptions: fiscal consolidation, balanced budgets, privatisation, employment creation and “active” social policies,” says Campillo Poza.

Like the other authors, she thinks that there is room for common struggle against the social and gendered consequences of austerity. “We cannot rebuild the European Social Model if the most important thing is that numbers tally. Of course, there are some countries that have more things in common. I am thinking of Ireland, Greece and Spain, which were hit really hard by the crisis and came to be depicted as the so-called ‘PIIGS’ (pejorative acronym for five of the economically weakest Eurozone states during the European debt crisis after 2008-2009: Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain)”, says Campillo Poza. “The three of them (Ireland, Greece and Spain), with different intensities, were the primary victims of rating agencies and the austericide agenda of the Troika,” she adds. There is no doubt that these reforms had clear effects on women, even if national welfare arrangements differ and filter reforms differently.

Greek youth still struggles with high unemployment (39,8%) while other social groups cannot afford a decent living. Moreover, women, young people and migrants face structural discrimination due to the patriarchy, racial and generational inequalities.

Apart from mapping the consequences of austerity policies on the lives of women, minorities and particularly vulnerable groups, these studies also give concrete suggestions for left-wing feminist politics, rooted in social justice and gender equality. The authors emphasise care activities which need to be valorised and socially reorganised, and at the same time as defended from their growing marketisation.

For example, as the German case study shows, there is a growing sector of employment – home care assistants – who are almost always women and often migrants. As the state does little to monitor this sector, there are neither reliable figures nor are there substantial rights or decent working conditions for the women employed in the sector. It is estimated that up to 300,000 eastern European women travel to Germany as ‘circular migrants’ for periods lasting several months, where they work as live-in carers in private homes offering round-the-clock care. Such arrangements engender a certain type of dependency and the risk of extreme exploitation.

To conclude with Oksana Dutchak’s words, “capitalist exploitation of mostly female, unpaid reproductive labour is at the core of gender inequality.”

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)