In the last year and a half, Beijing has been undergoing a “beautification campaign” during which many of its streets and alleys have been changed drastically. As a part of this campaign, many bars and spaces have been closed down, moved or reopened elsewhere, which is a topic of many a conversation between its residents. Beijing hutongs have also been undergoing this campaign. Hutongs are small alleys in the city centre and most of the people there live in so-called dazayuan which are a type of square living compounds.

The majority of the city outside the centre, which is the core of Beijing, was constructed after 1949 as a socialist city, so to many residents and visitors Beijing hutongs represent a view into old Beijing. As the population in Beijing started to grow, the government allowed people to build such dazayuan compounds, in which a lot of illegal structures were erected to make space for the all the people who were coming to the city. What the government is trying to do now is return them to the siheyuans (traditional square courtyards surrounded with a building by all four sides) in the style of Ming and Qing dynasties. But as locals point out, by doing this, the entire history of these streets and compounds over the last 50 to 70 years is being erased. What is necessary is a dialogue between all the involved actors – the government, residents, and academia – in order to find the most suitable solution.

The majority of the city outside the centre, which is the core of Beijing, was constructed after 1949 as a socialist city, so to many residents and visitors Beijing hutongs represent a view into old Beijing.

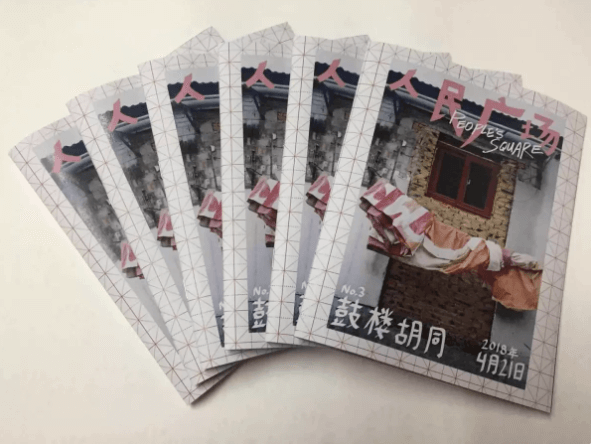

Many collectives in Beijing explore these changes in the city’s urban landscape. One of them is the Sponge Gourd Collective. “A loofah for the future, a squad of green goons, a slimy surprise”, as they describe themselves, they are documenting the changes in the urban environment – most notably in Beijing’s hutongs – through their zines and art projects. The Collective published three issues of their zine, People’s Square (人民广场), in which they dealt with changes in three areas: in Changdian village on the outskirts of Beijing, Guijie street, the most famous snack street in Beijing and the Dongcheng hutong, one of the many hutongs undergoing the government’s “beautification” campaign. Their latest art project on the high-speed railway (HSR) is especially compelling.

Both their zine project and the HSR project delve into the communities – the Collective interviews people and observes what kind of cultural and another impact these various policies have. Their projects are long-term, especially the latest one dealing with high-speed rail. The Collective is trying to document how all of these projects and changes are affecting and influencing the communities in a city like Beijing, where the only constant is change.

Members of the collective were already working on gentrification issues in Chinatown in New York, so they were interested in the same type of changes that were happening in Beijing and China. Beatrix Chu, one of the members of the collective, explains how the constant changes that happen in Beijing and China influence the affected communities – she says that what happens is that people simply don’t know how everything will look in a couple of months and years. This leads to people becoming numb to ongoing changes, but Chu emphasizes that when she talks about the changes in the urban environment, she does not merely refer to “the changes in the architecture, in the buildings and structures”, but more “the transformations in daily life”. The constant changes “create a deep sense of instability”. She stresses that the organization of the areas which they addressed in the three zines is “influenced by the way people live,” which can appear disordered. The effort now is to make everything “cleaner, more orderly and organized, so when people from the outside come and see, they have an impression that the environment is very controlled”. Chu also points out that that type of development does not represent or reflect “organic growth of the community, but the change is rather determined from the top-down”.

In their approach, the Collective talks to people in the community because they want to understand their perspective and their side of the story, as this is a very important part of their work – “always listening to what people have to say, understand[ing] their side of the story, not projecting what we believe”. As Chu says “some people actually want their apartments to be demolished and [they want] to get the compensation money,” which might be at odds with our own inclination toward preservation.

Beatrix Chu, one of the members of the collective, explains how the constant changes that happen in Beijing and China influence the affected communities – she says that what happens is that people simply don’t know how everything will look in a couple of months and years.

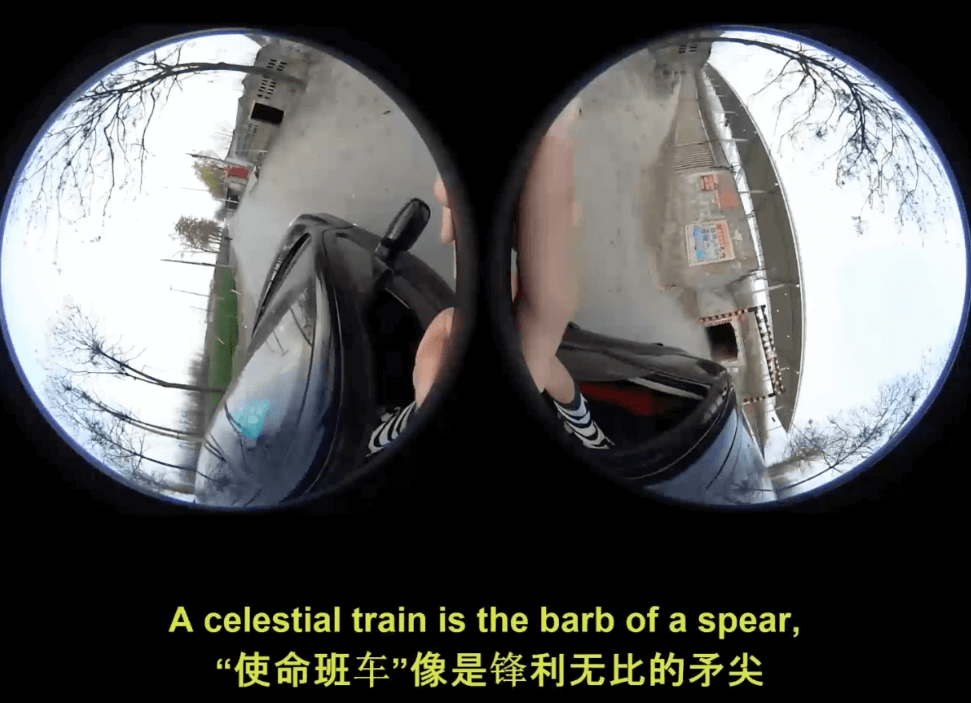

The Collective showed a part of their most recent work titled A Day in the Outer Ring at the exhibition space iprojectspace in Beijing. It was the first physical exhibition within the framework of their broader project called The Harmonious Commute – “a narrative project documenting Beijing’s high-speed rail (HSR), its trajectories and its emerging cultural impact which will integrate Beijing, the neighbouring city Tianjin and the province Hebei into a single entity called Jing-Jin-Ji”.

Why the high-speed railway? Chu explains how, as a collective, they thought about the region of Beijing and its expansion. It seemed to them that the HSR was a symbol of the expansion of the city, but it was also a symbol of growth and expansion in a global sense because the planned network of fast trains should reach places as far as Thailand and Amsterdam. As the world’s longest high-speed network, China’s railway network and high-speed trains have become somewhat of a symbol of China’s growth, progress, and rejuvenation.

She emphasizes the importance of technology and says the railway is “an obvious representation of speed – how the train works, in general, how it contracts space and time”, so the Collective thought it to be a potent symbol for the general development of the country. “It is supposed to be connecting everything”, she continues, “but also at the same time it is flattening [everything]”. It brings progress, but also unification. The Collective wanted to explore and research the promise of the railway – the promise of progress an hour away from Beijing, the progress that comes with speed, with travel, with new business opportunities. But questions emerge: What is happening to those places?; How does the HSR impact nearby landscapes?; What do you see when you look at the window? Thus, the Collective used railway routes “to map out and track changes in the area”.

As the world’s longest high-speed network, China’s railway network and high-speed trains have become somewhat of a symbol of China’s growth, progress, and rejuvenation.

There is no doubt that a railway and the construction around it influences the urban landscape – at the same time, it symbolizes both a beginning and an end, change, and uniformity. During their research for the project, Sponge Gourd Collective went to places where a station of the HSR network was already present, where the stations were recently built, but they also went to some places where the routes are only planned to be built in the next couple of years. Chu adds that sometimes the train stations influenced the community by making the prices of real estate go up. There was a lot more real estate speculation, as well as new developments. In places where there is no train station yet, the people were aware of its construction, but “did not necessarily expect it to change their lives drastically”. It might provide faster and easier access to the big city, but only to those who can afford it. The official narrative is that of prosperity. It remains to be seen how the development and changes the HSR brings will unfold.

***

Matea Grgurinović is a Croatian journalist writing mostly about social issues with a strong interest in Southeast Europe, China, and the post-Soviet space.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)