We do not have the luxury to simply wait and hope that the situation will change in the future. We need change now.

Krytyka Polityczna: 15 months ago, refugees in Germany decided that they would no longer accept their miserable living conditions. They left the Lagers* where they are forced to live, marched in protest through many cities and, upon their arrival in Berlin, occupied two spaces from which they have continued to organize. Why did you join the movement?

Napuli Paul Langa: I came to seek asylum in the city of Braunschweig in July 2012, and was placed in a Lager where I was deprived of my self-determination. I was isolated from the outside world, and stripped of my privacy. The Lager authorities didn’t know or care about why I was here or who I was. I had brought all the documents and resources of my organization with me to Germany in order to re-establish it here, but I couldn’t do anything because I was held like a captive. Then, I found out that everyone else in the Lager was experiencing the same life. So I refused to accept this condition. I knew I had to do something.

*“Lager” (literally “camp” like in internment camp) is the German word for a specific type of house where asylum seekers are obliged to live.

What organization had you been working for before you came here?

It was never my plan to go to Europe. As soon as I arrived, I ended up in this prison called Lager.

In 2004, I joined the Sudanese Organization for Nonviolence and Development (SONAD) because I saw what people in Sudan were going through. But in 2011, I was expelled by the dictatorial government because we were too critical of their policies. There are not many options in a case like this: either you are killed, put in prison or you flee.

What did they do to you?

They tortured me for four days. Then they released me under a condition: As I was responsible for the finances of SONAD, I was seen as the key to its elimination. They had also begun to target other organizations, including Save the Children, so they needed me to figure out how the money was flowing and which organizations were involved.

They wanted you as an informant.

Exactly. This is when I ran away. I went to Uganda and founded my own organization because I don’t see myself as a victim. Wherever I go, I will fight for the right to live freely. So I established the Sudanese Activists for Non-Violence and Human Rights organization. Before it was registered, the government launched a crackdown on many oppositional organizations. So I had to leave Uganda and this time I went to Europe. It was never my plan to go to Europe. As soon as I arrived, I ended up in this prison called Lager.

How did you get in contact with the movement?

The Refugee Bus Tour, which visited dozens of Lagers throughout Germany in order to inform other refugees about the movement, came to my city. So I joined them. In October 2012, after our arrival in Berlin and the occupation of Oranienplatz (a public plaza located in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, Berlin’s most alternative district), we organized a big demonstration that was supported by thousands of people. As there was no reaction whatsoever from the politicians, we decided to stay at Oranienplatz and set up a protest camp until our demands were met: the abolition of the Lagers, abolition of Residenzpflicht* which forbids us to leave the city where we are accommodated, and the cessation of deportations. We also started to build networks on a transnational scale. In July 2013, I travelled to six European countries in order to establish contact with refugee activists.

*“Residenzpflicht” (German for “mandatory residence”) is a German law that obliges asylum seekers to live within certain geographical boundaries in Germany defined by their Lager authorities. It is a unique law in Europe, and was considered a violation of human rights in a report by the United Nations.

How dangerous is it for you to travel?

It is quite dangerous because if they stop you, they can imprison or deport you. My lawyer advised me against it, but I believe that justice will not come easily. In 2014, we will concentrate our actions on Brussels where the people and institutions responsible for deportations and killings through Frontex are based. This movement is about the broader picture: the German and the European asylum policy. If somebody dies at Oranienplatz, that death is the responsibility of the authorities. Mohammad Rahsepar — the refugee who killed himself in his Lager in Würzburg, thus prompting the protest march to Berlin — was not committing suicide. The German government killed him. He could no longer bear the inhumanity of this existence: the isolation, the controls, and the indignity. We all have had enough.

Which was the driving force behind your involvement in the protest: the urgency of change or the hope that some change would come about?

There are things that are important, but not urgent. Then, there are unimportant things that are urgent. Our struggle is both important and urgent. People are dying every day; we do not have the luxury to simply wait and hope that the situation will change in the future. We need change now. We are, once again, being threatened with eviction from our protest camp by the German government. Let them come. We will see what will happen. We will do whatever possible. They don’t know what we are planning. So it’s better for them to give us our basic human rights before things get worse.

One has to understand that here our lives are not normal; we cannot function like normal human beings.

How did the movement change over the course of the last 15 months?

One has to understand that here our lives are not normal; we cannot function like normal human beings. In the Lagers, the authorities wield total control; our rooms are subjected to daily searches, every morning at 6am; the authorities have keys to our rooms and can enter whenever they please. We are not allowed to work or to send our children to school; we are supposed to only eat and sleep, like animals. The Lagers are fraught with fighting, mainly because of overwhelming frustration. At the protest camp, we have built an autonomous space where we have been able to gain some self-determination. Here, we are at least addressing our problems; we are here for one another. In a very general sense, my participation in the movement is about my sense of self. No one here wants to be a refugee. But it can happen, and when it does, we have to support one another. What is most important is that Oranienplatz still exists and our fight continues.

Have you seen some positive developments since the commencement of the movement, like the growth of popular support?

It’s true: we have managed to enlarge our solidarity network. We receive a lot of support from German citizens in terms of food, clothes, financial resources, education and so on. For example, there are students giving free German classes to refugees at the occupied school5 in Kreuzberg (The Gerhart-Hauptmann-Schule, a former school, was occupied by refugee activists in 2012. It serves both as a political and living space and accommodates several hundred people). We also receive political support: Many groups and organizations are now fighting for our demands and spreading our message. Our networks have expanded over the course of time. Now we are able to mobilize 500 people within minutes and 3,000 people within one week. This is our current mobilization potential, and it is growing.

There is nowhere for us to go, other than to prison. We need this space in order to remain visible to the public.

Some politicians claim that they support the refugee protest but disagree with its form; they see Oranienplatz as a public place that belongs to the city and therefore an inappropriate location for the movement.

Then they must tell us another place. We don’t want Oranienplatz either. Who wants to be in that freezing place? But there is nowhere for us to go, other than to prison. We need this space in order to remain visible to the public. Their demand is out of the question regardless; it is we who choose the form of our resistance, not some politicians who are responsible for our condition in the first place. As soon as our demands are met, we will leave. Apart from that, if they are supporting the movement, but not our protest camp, they are just playing politics. Real solidarity means that when you agree on the same goals, you don’t withdraw your support simply because your “allies” choose a different path to reach that goal. In 2012, in the first days of the occupation, a group of refugees decided to go on hunger strike at the Brandenburg Gate — the symbolic center of the capital. Some of us thought that such a move was premature, and that we should consider it only as a last resort. But the group chose to do it, and of course we stood in solidarity and supported them. This is how one can learn to differentiate between real and opportunist supporters.

In addition, some of these self-proclaimed supporters recently discovered their humanitarian side: They publically raised their voices to save the refugees from the bitter cold that reigns over Oranienplatz in winter.

It’s politics. They don’t care if we are freezing or not. They thought that we would abandon the camp by ourselves after a while, but we stayed. Once they realized that we were determined, they had to shift their tactics. Now, they either demand eviction “for our own protection” or they claim that we violate the law and therefore must be evicted.

A few months ago, the district government responded to the demand of refugees to provide decent accommodation. The district rented a house in order to temporarily accommodate the refugees from Oranienplatz in exchange for the eviction of the protest camp.

This deal was a sham. Besides the fact that those who found a place there have to leave again in a few months, the house accommodates only eighty people. What about the others?

I told Herrmann that she is on the wrong track and that she is suppressing people. She refused to hear me.

At the time the deal was sealed, it was said that there were eighty people living at Oranienplatz.

They lied. I was there. Monika Herrmann…

…the mayor of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, the district where Oranienplatz and the occupied school are located…

…made secret meetings with a contingent of the refugees. She negotiated only with the Lampedusa refugees who have no chance of receiving asylum due to the Dublin II Regulation* and who have no accommodations here. She knew that it would be easier to negotiate an eviction of Oranienplatz with the Lampedusa people because many of them, out of sheer necessity, primarily demand a place to live. This is why some of them eventually made the deal. We support the people who now have a house, but many of them didn’t realize what the deal would mean for them because they were not made aware of their realistic options. They were dragged into this decision by the government. I told Herrmann that she is on the wrong track and that she is suppressing people. She refused to hear me. So she tried to create a division between us in order to more easily evict our camp.

*The Dublin II Regulation determines that refugees can seek asylum in the state through which they first entered the EU. Germany is entirely surrounded by states that ratified Dublin II, which practically means that the German authorities can easily deport refugees who came through the neighboring countries without checking the asylum status.

But the eviction was ultimately prevented.

Yes, but this was only because we strongly defended the space. We mobilized hundreds of people and blocked the riot police from entering. Now we have the Oranienplatz and a house. Therefore, in retrospect, we also played a game.

Do the authorities place additional pressure on refugees who are politically active?

Yes, they do. For example, they increasingly penalize people for breaking the Residenzpflicht. Moreover, your participation in political demonstrations or groups has a negative impact on your asylum process. Right now, they are trying to split us into “radical” and “non-radical” refugees; into bad and good refugees. The ones who are labeled radical are either excluded from negotiations or are facing consequences with regard to their permission to stay here.

Are more people getting deported?

Many people have been deported already. Some of us are in prison, either in deportation prisons or regular ones. People disappear suddenly, from one day to the next. It’s horrible. On the other hand, some of those who have been deported are coming back, even if they have to risk dangerous transit on the Mediterranean Sea again. The politicians don’t realize that they cannot solve the refugee problem through deportation; they simply aggravate the situation. They can deport as many as they want, but people will still come. They don’t examine the root of the problem; they don’t even ask the question of why these people are coming.

What has been the impact of the global revolutionary uprisings since 2010/2011 on the Refugee Movement?

Before, there was no connection between movements. In Greece, where the refugee situation is really horrible, the migrants’ movement organized demonstrations. There were also actions in France, Poland and Italy, but they were not synchronized. Now, we are organizing on an international level. We build networks and share experiences. The global uprisings raised the awareness that we have to act in solidarity.

A current strategy by politicians and the corporate media is to claim that left-wing activists are instrumentalizing the refugees to suit their own political agendas.

Those who say that are the ones who instrumentalize us. They use our struggle as propaganda against their political enemies. You don’t have to be very clever in order to grasp that it is mainly the politicians who are trying to use us, by making secret deals, by dividing us, by deporting us. The Refugee Movement is a self-organized movement: we initiated and built it, and we are organizing the actions. No one who has lent us support in terms of resources and political mobilization has ever tried to tell us what to do.

They claim that these activists are creating false expectations and unrealistic hopes.

I don’t have hope that someone else will do it for me. I do it myself. Right now, for example, I am breaking the Residenzpflicht, which is an inhumane law that deprives refugees of their freedom of movement. So I am already practicing what I want to achieve; I am not dependent on a vague hope that this law will be abolished in some distant future. The important thing is to take action.

What about the other two demands: the abolition of the Lagers and the cessation of all deportations? Are they realistic?

By any means. The Lagers are concentration camps. So they have to be abolished. It’s as simple as that. I mean, for us it is not even realistic to exist. Everything around us is completely unrealistic. For example, it is not realistic that we don’t have houses, don’t even have a place where we can live in freedom and self-determination. And what is the reason for the Residenzpflicht? I am already in Germany, why can I not move or visit other people? This is madness. If you read Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights*, you will see that the Residenzpflicht is a violation of our fundamental human rights. In this context, which side is realistic and which is not? Everything is possible.

*The article states that: “Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State. Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country.”

Do you think these demands can be achieved within the current system — that of nation states, geopolitical wars, capitalist exploitation and institutional racism — or do we need more fundamental change?

One the one hand, the achievement of demands doesn’t require a big change. For example, we are told that there is no place for us to live apart from the Lagers. Recently, the German government decided to accept 5,000 Syrian refugees. Suddenly there are houses, which means that the achievement of our goals is matter of political pressure on the existing institutions. On the other hand — and here I agree with you — we require a more fundamental shift in the mindsets of many people. The government finds itself in a paradoxical situation: Why do you invite more refugees to your country when you are suppressing the ones that are already there?

It is as tough they wish to superficially redeem themselves for the substantial mistakes of the past.

Why do you invite more refugees to your country when you are suppressing the ones that are already there?

Exactly. Equally, the global spread of NGOs promoting development work in “third world countries,” or sending students there for “cultural exchange”, is almost schizophrenic. You have to change your own behavior before you can facilitate someone else’s. If I am a violent person, I cannot teach non-violence to someone else. True social transformation works according to “do as I do,” but the powers that be are saying: “Do as I say!” In other words, why are they aiding the poor without addressing poverty? Why don‘t they change the system that produces poverty? It’s absurd.

How can the protest be supported?

You can do a lot: spread our message in your channels, raise the awareness of your friends, hold seminars about the refugee problem, share information on social media, organize solidarity actions, put pressure on politicians and the media and so on. I know that many people ask themselves this question, but I think that they already know the answer when they think about it and know our situation. They just need to do it. There are many ways, and every one of us has different skills that can be useful.

The Interview was published in “GLOBAL ACTIVISM”, a special issue of Krytyka Polityczna magazine and Autonome Universität Berlin. The publication complemented the exhibition global aCtIVISm at the Center for Art and Media (ZKM) in Karlsruhe in 2013/14.

Napuli Paul Langa was interviewed by Daniel Mützel.

Comments in italics by Daniel Mützel.

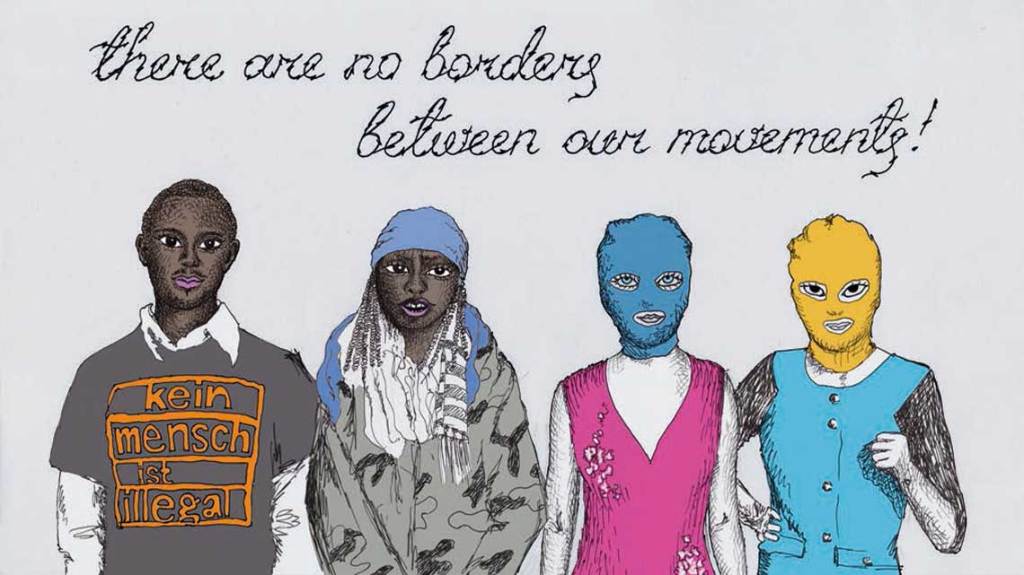

Drawing by Joulia Strauss

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)