Mazara del Vallo is a fishing port on the West coast of Sicily situated 200km across the sea from Tunisia. Aside from a Norman wall and couple of Baroque churches it doesn’t look like much these days, little more than a rugged seafront lined with empty hotels and rusting trawlers. But it’s a site of immense historic importance. It was here, a thousand years ago, that the Arab general Asad ibn al-Furat led the Aghlabid conquest of the island, a victory that would transform the predominately agricultural society into one of the wealthiest and culturally advanced regions of the early modern world.

Northern Italians prefer to trace their contemporary origins to the more recognizable banks of the Tuscan city-states.

It’s a story that has been largely forgotten by Northern Italians who prefer to trace their contemporary origins to the more recognizable banking families of the Tuscan city-states. Yet it was the Sunni Aghlabids and their successors the Shiite Fatimids, who pioneered the scientific and cultural advances that would revolutionize the island and ultimately Italy itself, bringing irrigation, universities and a new legal system among other key aspects of civilisation. As an emirate, Palermo, Sicily’s capital, was one of the most powerful cities of medieval Europe, governed by a multi-cultural, multi-lingual court in which Muslims and Christians worked side by side as scribes and translators as part of a cosmopolitan state.

Today such prosperity is a far off memory. Western Sicily is one of the poorest regions in Europe, crippled by corruption, underdevelopment, and a stagnant economy projected to return to pre-crisis levels only in 2028. In such grim economic conditions one might expect to find burgeoning support for neo-fascists who, elsewhere in Italy, have succeeded in turning the local poor against even poorer refugees many of whom wash up dead or alive in places like Mazara. In Milan earlier this year, to take just one example, a group of po-faced far-right activists set fire to some kitsch promotional palm trees that had been erected by Starbucks in the city’s central piazza on the basis that they encouraged the ‘Africanisation’ of Italy.

Due to its geographic and historical affinity with the southern Mediterranean, many locals here identify more with Tunis than Rome.

The dominant attitude in crisis-ridden Mazara is if anything the opposite. Due to its geographic and historical affinity with the southern Mediterranean countries, many locals here identify more closely with Tunis than Rome. “We’re proud of our origins as Sicilian-Arabs” says Davide, my guide, “our history begins with them, they transformed our land, our work, our way of life.”

The most evident sign of this reverence is the rebuilding of the casbah (the Arab town centre), a project that has been led in recent years by a community of Tunisian and Sicilian fishing families, keen to reinvent the town’s historic cosmopolitanism for a new generation. Tunisians make up a large percentage of Mazara’s population, having returned after a period of persecution to work aboard the fishing boats that drive the local economy. Today their presence is evident in the Arab community centres and schools, the shisha pipes and backgammon tables that line the town’s streets.

The significance of Mazara is about a genuine, fluid exchange of identities.

The significance of Mazara, however, is about more than visual paraphernalia, but a genuine, fluid exchange of identities. The fish market is a good example, with its mix of Italians and Tunisians selling side by side. Many of the boats are staffed by teams of diverse races, cultures and religions. This reality of Sicilians and Tunisians, Muslims and Christians, atheists and others at sea for weeks without any significant violence is quite normal for these people but, in the context of today’s sectarian divisions, must surely be considered remarkable. “At the end of the day, for most of the people here, far back enough, are Arab, or Norman, or German,” laughs Davide. Ethnicity is hardly a stable basis for identity in a place like Mazara.

Jalila, a chef, born in Tunis but resident in Mazara for most of her life is another case in point. “In my restaurant I’ve got a Tunisian flag next to a photo of the Pope” she says, “we’re all children of God and there is no difference for me between Tunisians and Italians”. Her Sicilian-born children help her cook fish couscous which is served daily to the casbah’s famously epicurean residents. Jalila frames it as Tunisian food, but this dish has been a staple in this part of Sicily for centuries, since the Aghlabids, and variations are found across the entire province where it is thought of by many as Italian cuisine.

The story of the fluidity of culture is being told on the walls, in public artworks, tiles and murals spread out around the casbah.

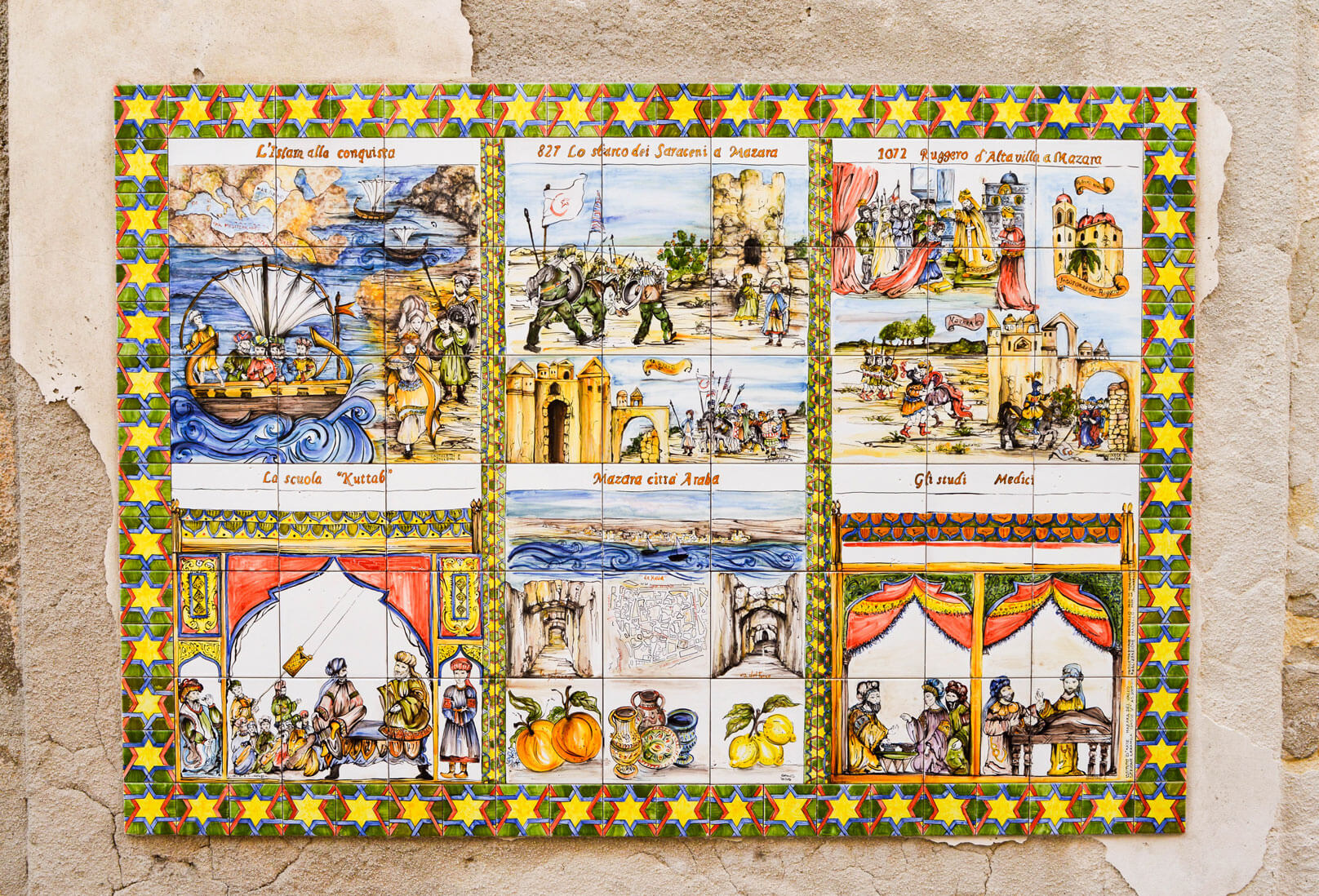

Andrea, a sculptor from Veneto, is insistent on the importance of this unwinding of identities. “The refugee crisis has brought a lot of division, but it is also an opportunity for us to reframe what it means to be European beyond rigid identity politics. In this sense Mazara, and its history, has a unique message about the fluidity of culture.” This story is indeed being told, on the walls, in public artworks, tiles and murals that are spread out around the casbah, depicting the Aghlabid origins, yes, but also the story of the Normans, Jews, and Spanish. Perusing these makeshift installations is a strange experience. It is not, as some might assume, a crude attempt at gentrification. This part of Sicily is far too isolated for that term to mean much, at least for now. Even in August there are almost no tourists in Mazara. It is the locals, new and old, who are working to rebuild it.

Not everyone is happy with the initiative. Parties like Fratelli d’Italia and Nuovo Centro Destra are working hard to propagate the myth that Mazara is a hotbed of ISIS recruiters, hoping to capitalise on the Islamophobic discourse perpetuated by the Italian media. Thankfully so far this has had little impact in the town itself. Nevertheless in recent years many of the town’s richer residents have chosen to move from the historic centre to the more modern ‘private’ suburbs, away from the casbah and its specific mixing point of cultures. This is the opposite, in a sense, of what is happening in most European cities. The elite is fleeing to the periphery while the people take over the centre, rebuilding it on their own terms for the commons.

The casbah can be seen as an attempt to build a community beyond the confines of nation-state: a defiant utopia of the Mediterranean.

There is a long way to go. Most of the houses in the casbah are still empty, the garbage, as with the rest of Sicily, festers in great piles while cockroaches scuttle on the pavement, the water supply is heavily rationed and wiring on most of the streets looks ready to go up in flames at any second. Yet for all this the project is a powerful celebration of pluralism, and an inspiring counter example to a Europe of growing intolerance and xenophobia. More tenuously yet perhaps more profoundly, the renovation of the casbah can legitimately be seen as an attempt to build a community beyond the static confines of nation-state: a defiant utopia of the Mediterranean.

***

All photos courtesy of the author with the exception of the lead image, taken from Gentes FB. Some rights reserved.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)