When I ask him if he has any plans for the future, he just shrugs his shoulders: “Here? Here there is no future. Prison was bad, but you don´t find your future outside either.”

He offers me a cigarette, and we stand in silence. A boy sitting on scorched grass watches as we say goodbye and gestures to beckon me closer. He’s from Pakistan and must be underage. When I ask how old he is, he says: “10 Euros.” This short reply echoes in my ears for a long time. 10 Euros: the price for which he prostitutes. The price for a human body.

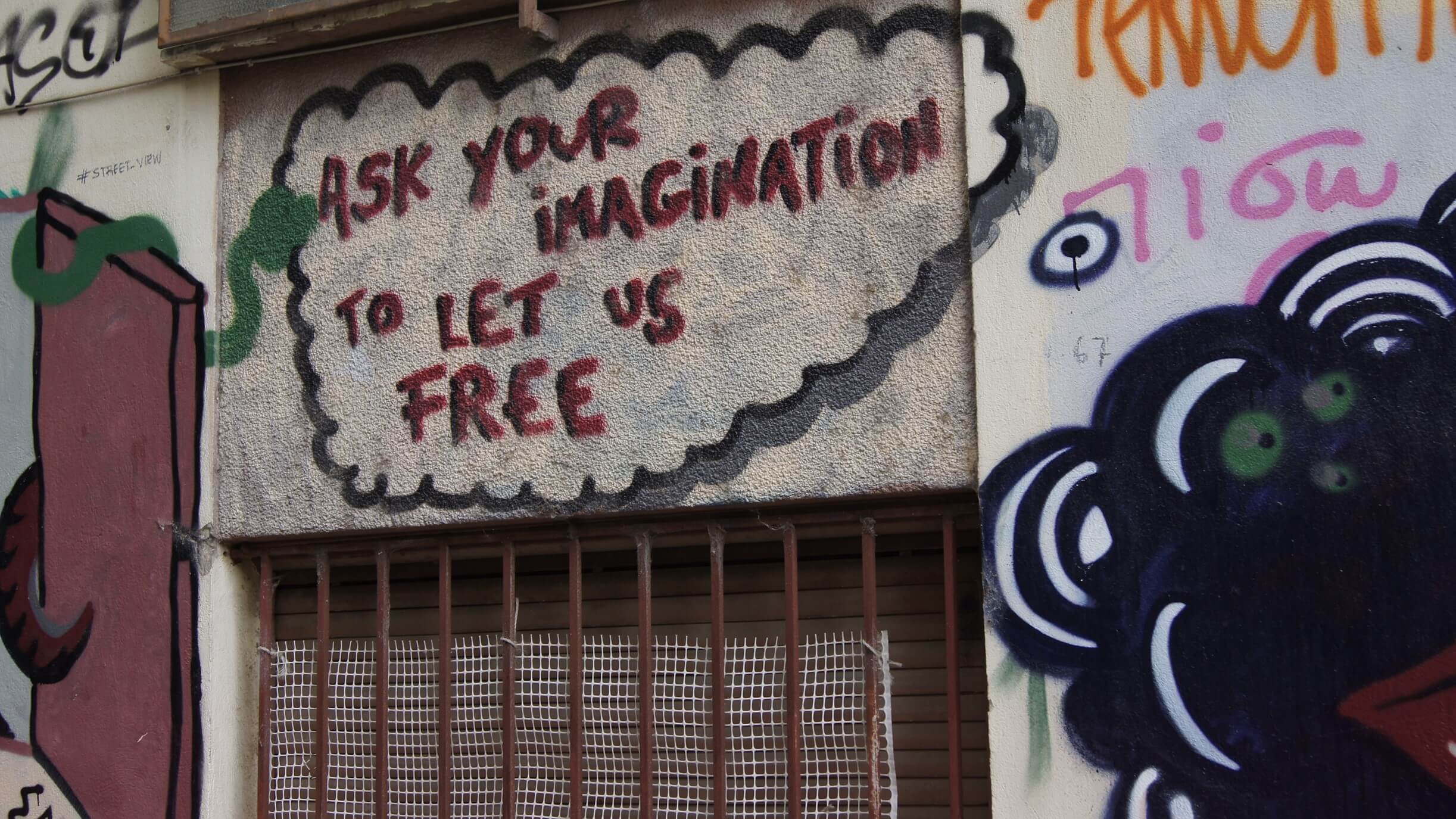

We’re in Athens, one of the focal points of migration towards Europe. But if you stroll in the city centre, you’ll also come face to face with victims of the recent devastating waves of debt crisis and subsequent cuts, which afflicted all Greeks. All these people have been forgotten. When prisoners behave well, as the old maxim goes, nobody is interested in them. It’s only when they try to revolt that the TV vans appear.

For Michel Agier, an expert on migration, the current policies aim to consolidate a partition between two categories of world that are increasingly separated from one another. On one side, apparently, is ‘our’ clean, healthy, visible world. On the other is a dark, malignant and invisible world, one we do not want to see. Yet we’re suddenly confronted with that reality through increased mobility, forced migration and the ‘relics’ that this migration has produced: all those ‘Undesirable’, ‘Unneeded’, ‘Unwelcome’ immigrants and refugees in refugee camps in Europe, which are often situated on the peripheries of towns.

It is they who have arrived at the threshold of our world, which has no interest in them. Its consciousness of them is only as a side effect of the production of inequalities, as ‘relics’. This is true whether they are economic migrants, displaced people or all those who, as the sociologist Saskia Sassen defines, fundamentally exceed these insufficient categories. Those, for example, who have lost their original environment as a direct consequence of economic ‘development’, or left places with dry or contaminated soil.

Witnesses to the economic crisis

Living conditions in Greece have deteriorated for local people too. Unemployment, for example, has risen sharply. Many of those you meet at the makeshift dwellings along streets and in parks – where some sell drugs or their bodies to passers-by – have lost their homes.

Besides locals, you also find those who have been coming to Greece as part of seasonal migration, especially from the Balkans and Near East, since the 1990s. “You won’t find any work here, and if you think you earn some money as a seasonal worker, you’re wrong”, despairs an old man of Bulgarian origin.

He alludes to one of the acute problems that the economic crisis has brought with it: widespread labour exploitation. Seasonal migrants work mainly in agriculture as fruit and vegetable pickers, harvesting oranges, olives, tomatoes and melons. As foreigners, sometimes employed illegally, they often get no money for their work.

The question of migrant labour exploitation in Greece is rarely mentioned in the media, let alone addressed by politicians. Given Greece’s economic situation, and the growing polarization of society, with a large portion of the population tending towards the far-right extremists from Golden Dawn, the theme is considered comparatively unimportant.

The story of Muhammad, an Iranian man who came to Greece in 2000 to find a job, is just one example of the fatal impact the economic crisis has had on people´s lives. Until 2008, he worked for eight months a year as a paver of local roads, followed by a spell of temporary season work before serving time in prison and then living on streets. Now he lives in a park.

This is where we meet, amidst a shocking scale of addiction to heroin and synthetic shisha, a street variant of crystal meth nicknamed the ‘cocaine of the poor’. He beckons me to sit down on a bench, without, unlike the park’s other inhabitants, trying to sell something from the content of his pockets, or offer ‘discount’ sex. He guides me through this place which reminds me of a tangle of languages from the proverbial Babylon.

Servants to heroin

The monotonous sound of cicadas floats among the trees. Tens of men and women, old and far too young, either rest or gesticulate wildly depending on whether they’ve had a dose or not. “It’s not safe here.” We a choose a bench a little further away and light up our cigarettes. Muhammad begins to talk shyly, facing the ground. “My boss dismissed me, only half of the people could stay there. If you’re a foreigner you can’t get a job.”

Although Muhammad has learned the local language, this doesn’t help him at all. Like most migrants he tried to resolve his work situation by picking olives. He even left Athens, but the conditions at the harvest site did not correspond to the promised daily profits and on top of this the local foreman cheated him and his friend out of their wages.

After that, he was sentenced to two years in prison. Apparently he didn’t have all the documents necessary to stay in Greece. Later, when he left the prison walls without a euro in his pocket, he became an inhabitant in a park near the local university.

He lives by selling hashish, and uses crystal and heroin. “Tourists come and everybody wants something today. I don´t earn more money than for food and cigarettes. But frankly this is enough to survive.” He’s nervous about the area and pricks up his ears as somebody comes towards us.

Darkness falls. The cicadas are louder than ever as they anticipate the end of the day and the arrival of night. Candle flames flicker in the dark and those waiting for a dose sit around them like around a fireplace, like servants to heroin. This is a dump for human bodies of all nationalities, with no distinction in their status. All here are without a future. Random bodies controlled by demons in this space with sunburnt grass, shrubs and trees that partially hide their parallel world.

A dump for human bodies

Panaiotis is one of the Greeks who found himself on the street during the crisis. Now he spends his nights in the park. “I haven´t eaten for two days. My Mum and Dad are dead, they had a car accident two years ago.” He talks about the moment that brought him to heroin, “when I don´t have it, going cold turkey is terrible. But shisha will get me off it.” One gram of shisha, from which several doses can be prepared, costs between fifty and one hundred euros.

The drugs are accompanied by prostitution, and the clientele consists mainly of Greek men. When I ask Panaiotis if he too lives by sex work he doesn’t respond, but tells me about prices which are in the region of tens of euros. “Some new young boys have come from an island here” he explains, gesturing to some nearby migrants. “They couldn’t tolerate the camps anymore so they found themselves on the streets. That’s where you encounter the drugs.”

Some sell drugs together with the locals, earning money for them at the same time. For others prostitution is the only chance to get money for drugs and something extra for food. “Some of them solicit for drugs, some for money,” says Muhammad.

They may be victims of one of the mafia gangs dealing with drugs, prostitution and smuggling, which target migrants in the refugee camps, where they find a fertile-breeding ground. These peoples’ situation can bring them to desperate acts. Many believe that the world has forgotten about them.

More and more people gather at benches in the park and Muhammad gestures at a distance that it would be good to disappear. We move quickly to a different section and the scene is quite different to that which we witnessed a minute ago. A single policeman – reading newspapers – pretends to ‘patrol’ the park from the safe distance.

The authorities tried to resolve the situation of people living on the street in the Exarchia district with night-time “cleaning” raids, deporting the unwanted from the city centre to collection stations outside the city. These were originally intended for the immigrants who were caught without a permit.

Like other important sectors of the Greek welfare system, social work aimed at homeless people, i.e. locals, immigrants coming during recent twenty years, and even some refugees – was essentially affected by the austerity measures. Many professional positions were substituted by organizations based on the principle of direct donor help.

“Many people who come to us to get free food have been coming for several years. They’re ashamed of this and would never speak with a journalist about it”, says one of the workers at an independent initiative, which tries to help those in need. According to him, more than half of the people on the street are working-age Greeks below the age of fifty.

In his view locals suffering the consequences of the economic crisis cannot find jobs as these are reportedly offered to immigrants. “Their labour costs almost nothing because they work illegally. They cannot take risks and call for labour rights because they have none. This suits their employers,” says Christa, a volunteer at the community centre in Chora.

The migrants describe an entirely opposite situation: they cannot find any legal work in the city because if any is available it’s locals that are preferred. The only thing they can do is to seek their fortune at farms where the owners take advantage of their status as temporary workers.

* Part 2 of ‘Stories from the Babel Archipelago’ will be published next week.

** This text was first published in Czech on Deník Referendum. It was written with the support of Strategy AV21, the research programme Effective Public Policies and Contemporary Society – Mobility. All photos are property of Michal Pavlásek. All rights reserved.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)