It’s late December 2017, and the huge Congress Centre in Leipzig, in eastern Germany, is teeming with people walking hurriedly in every direction. Many others are sitting on long benches along the wall, or on chairs, or on the ground, but all are invariably hunched over their laptops. There are LED lights everywhere, including on the people themselves, who wear them as bracelets or necklaces or on their clothes.

Sunset comes early and then inside the Centre there are laser lights and smoke and music, and in the middle of it all, there’s a shiny green space rocket called Fairy Dust. The scene seems appropriately chaotic but, as the saying goes, there’s a method in the apparent madness that is the Chaos Communication Congress, organised annually by the Chaos Computer Club (CCC), a German hacker collective.

With over 15,000 attendees, this Congress is Europe’s largest gathering of hackers ever.

With over 15,000 attendees, this Congress is Europe’s largest gathering of hackers ever. Apart from making space available for participants to set up camp and work on their things, there are over 170 talks and lectures. These range from the usual tech and hacking stuff (“Electromagnetic threats for information security”, “Mobile data interception from the interconnection link”) to cultural, scientific and political topics (“Net neutrality enforcement in the EU”, “Protecting your privacy at the border”).

No logo from a big corporation can be seen, as the CCC doesn’t accept that kind of sponsoring for the Congress. Except for the food catering and the toilet cleaning, everything else –from the ticketing to the fast internet to all the events happening on time– is run by volunteers who have organised themselves in a decentralised manner. And everything works.

“We are trying to build an environment with the Congress (…) to have a society that revolves around the same ideas we have”, says a bearded and soft-spoken man in his 30s who goes by the name “nexus”, his online handle, and is one of the few spokespeople for the CCC.

Those ideas are expressed in the hacker ethics, an informal code of conduct among civic-minded hackers that includes guidelines like “mistrust authority – promote decentralisation”, “all information should be free” and “access to computers –and anything which might teach you something about the way the world really works– should be unlimited and total”, as put in writing in 1984 by journalist Seven Levy.

“The hacker ethics tell us a lot about how a digital society should work like”, nexus says. “They give us a guideline, no strict rules but a guideline. (…) They let you interpret them”. In fact, the CCC adds two more principles of its own to Levy’s compilation: “make public data available, protect private data”, and “don’t litter other people’s data”.

Hackers come together to discuss and put in practice those ideas: freedom of information, right to privacy, decentralised self-organisation.

At the Congress, hackers come together to discuss and put in practice those ideas: freedom of information, right to privacy, decentralised self-organisation. “The basis is always sharing knowledge openly, seeking knowledge openly, trying to find out how things really work and how to influence them”, says rough-voiced Linus Neumann, 34, a freelance IT consultant and another spokesperson for the CCC. “And it makes very much sense to adopt that hacker perspective and take it to political challenges and issues, to look at political battles and discussions as interesting problems to which you need to find a creative solution”.

And, as it happens, the CCC hackers have been aiming to find creative solutions to interesting problems for over 35 years now.

Computer ‘freaks’ come together

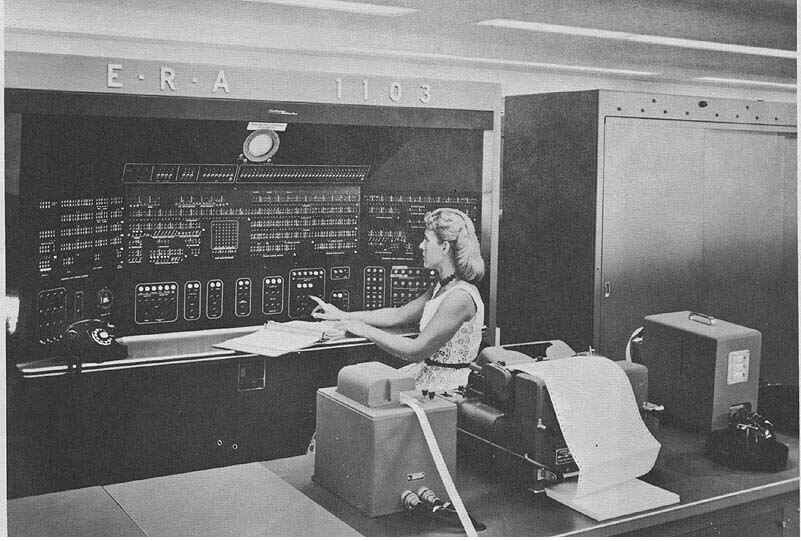

On 1 September 1981, a strange note appeared in German leftist newspaper Taz warning that authorities and corporations seemed keen to abuse them at the time emerging computer technology in their own interests.

“We believe that, despite all this, useful things can be done with home computers without a need for large centralized organisations. To keep us computer freaks from puttering about aimlessly any longer, we’re doin’ somethin’ and will meet in Berlin (on 12 September)”, said the note, titled “Tuwat” (German slang for “Do something”) and signed by Tom Twiddlebit and Wau Wolf Ungenannt, the nicknames of, respectively, Klaus Schleisiek and Herwart Holland-Moritz, known as Wau Holland.

“We thought, let’s try to organise the first meeting of computer experts to look into what the social ramifications of the computer were at the time and what we could foresee for the future”, says Klaus sitting on a sofa at the Congress. Now 67, very tall, with white hair and beard, he looks quite different from most of the generally younger people surrounding him.

Klaus and Wau, then living in Hamburg, came from a post-1968 anti-establishment and anarchist political background and didn’t like centralised and opaque systems, neither technological nor political. They were part of the anti-nuclear movement and got police beatings during demonstrations, “and that made clear to a lot of people how the system works”, Klaus says. “We had to count on our own strength and do our own thing, and start things, and organise things”.

In their “Do something” note, Klaus and Wau wrote in eerily prescient words: “We’ll talk about: international networks – communications law – data-processing law (who owns my data?) – copyright – information and learning systems – databases – encryption – computer games – programming languages – process control – hardware – and whatever else”.

“I’m still standing in awe in front of (our text) because it’s worked exactly the way it predicted more than 30 years ago”, Klaus says.

Today many people worry about those issues or at least have heard about them. But this note was published back in 1981 when the word “internet” wasn’t still being used and very few people owned or knew anything about computers. “I’m still standing in awe in front of (our text) because it’s worked exactly the way it predicted more than 30 years ago”, Klaus says.

Days after the note was published, Klaus, Wau and three colleagues of theirs, the self-described “computer freaks”, welcomed the two dozen people who had answered the call to meet on 12 September in Berlin. This was the first public meeting of what would become the Chaos Computer Club.

‘Computer Robin Hoods’

In those first meetings, the hackers were both worried and hopeful about computer technology. When in 1983 the West German authorities wanted to carry out a census and develop machine-readable ID cards, Klaus and Wau spoke of a counter-concept: why not go for machine-readable governments instead? Computers shouldn’t turn into a technology of abuse by the authorities when these machines could actually empower citizens to hold governments to account.

In the end, the Constitutional Court aligned itself in general terms with the hackers’ thinking and ruled the planned census was too invasive and people had a right to informational self-determination: “the capacity of the individual to determine in principle the disclosure and use of their personal data”.

Klaus ended up going his own way and stayed only on and off connected to the CCC, but he remained close friends with Wau, the Club’s charismatic founding father, and its life and heart until his death in 2001, when he was 49. Those who knew him describe Wau as a gentle visionary with a special talent to communicate complex concepts and to make people open up and discuss anything.

It was Wau who came up with the name Chaos Computer Club, and who in early 1984 started publishing the still today irregularly appearing magazine Die Datenschleuder (The Data Slingshot). That first issue had just two pages and was a public letter of introduction by the CCC. It included articles about hardware, a hacker hymn and a programming challenge for those willing to join the club. That issue of the magazine reached a very few people – but only months later the Club would be known all over Germany.

In November 1984, the CCC warned Deutsche Bundespost, the state-owned telecommunications company, of security vulnerabilities in its BTX system, which allowed the transmission of paid on-demand text content through the phone network to be shown on a TV screen. The company ignored the warning, so the hackers got the BTX username and password of a German bank and used it to pay repeatedly during a weekend for content produced by the CCC. In the end, the hackers had taken 134,694.70 German marks from the bank (about 48,000 US dollars at the time).

On Monday, the CCC called a press conference, revealed the hack and gave the money back. “That was a very strong statement”, Klaus remembers still smiling mischievously today. The story was indeed sensational, and if in 1983 the film “War Games” had introduced hackers to the general public as smart but goofy teenagers who could unleash nuclear war by mistake, one year later the German media were describing the CCC hackers as kind of computer Robin Hoods.

The Club finished 1984 by holding its first Chaos Communication Congress in December. It was probably the first hacker conference in Europe and only around 100 people attended.

The Club finished 1984 by holding its first Chaos Communication Congress in December. It was probably the first hacker conference in Europe and only around 100 people attended.

As the use and misuse of computer technology were becoming more common, in 1986 West Germany made spying and manipulating data in third-party computers a crime. The CCC then had to become a legally registered Club based in Hamburg. “Some people hinted at us that we better become a registered association, as otherwise, the government might call us a criminal organisation, (and) that’s slightly more inconvenient that reorganising yourself and becoming registered”, says Andy Müller-Maguhn, speaking also at the Congress in Leipzig.

Andy, 47, severe-looking and today an IT businessman and consultant, had joined the Club in that year when he was 15 and a computer enthusiast excited about the possibilities the first connected networks offered. “Learning about data travelling, as we called in those days, was an experience that is today maybe a little harder to explain, because those days we felt empowered by using our cheap terminals, our home computers, to type something and have this imagination that at the other side of the planet some hard disk would move based on our finger strokes. That was for us like traveling to the Moon”, he remembers. “Today it’s the most normal thing on planet Earth, but (back then) was different”.

Meticulous and well organised, the young Andy helped steer the CCC towards a well-functioning organisation. “I got in there and there were unopened letters all over the place. The CCC had just become famous and no one took care of the people who wanted to get in touch. (…) And I kind of started to sort things, I established some structures with others together”, he says.

Not only famous but the CCC was also becoming a respected voice in the emerging public debate about computer technology, and already in 1986 the Green Party had sought the Club’s expert advice when considering to introduce computers to its parliamentary offices. But then everything changed.

‘Expulsion from paradise’

Starting in 1986, some young hackers –who were not members of the CCC– managed to infiltrate the networks of NASA, the CERN physics laboratory in Switzerland and other cutting-edge defence and research institutions in several countries. They had infected so many computers that they worried other people with bad intentions could also get access to the machines. In 1987, the youngsters told Wau and other CCC leaders about their hack and the Club passed on this information to the West German authorities, who didn’t react publicly, and to two journalists, who then broke the story about German hackers infiltrating NASA’s secret files.

Two years later the story took a Cold War twist when three young German hackers –including one loosely connected to the CCC– were arrested and admitted having sold stolen information from those European and American scientific and military institutions to the KGB, the Soviet intelligence service. The cyberespionage case made international headlines.

But, in the eyes of many, hackers, in general, had become tainted and gone from Robin Hoods to potential cybercriminals and spies.

No CCC member had been involved and the Club tried to distance itself from the sordid affair, which hadn’t been very much in line with the hacker ethics. “People who have worked for the KGB are not hackers to me, those who take money exclude themselves”, Wau said then to the press. But, in the eyes of many, hackers, in general, had become tainted and gone from Robin Hoods to potential cybercriminals and spies.

The CCC laid low for a while, some members revealed the German intelligence services had tried to hire them, there was an atmosphere of mistrust among the hacker community: it was “the expulsion from paradise”, as Wau called it later.

‘The power of definition’

Following the German reunification in 1990, Andy Müller-Maguhn opened a CCC chapter in Berlin, expanding it from its traditional base in Hamburg. And thanks to Andy’s energy and to the new members joining from East Germany, where almost everyone who had wanted to use technology had had to become kind of a hacker, the CCC gained a new life.

Members gave talks and participated in conferences, and the Club kept making IT and computer vulnerabilities public. In 1993, the CCC revealed how the Microsoft Money software could be abused to steal from people using it. The next year, after IBM boasted in an ad that the most dangerous hackers were at IBM and not in jail, the CCC exploited a vulnerability in the company’s free software samples to show how to use the full programmes without paying. In 1998, the CCC announced it was possible to copy a SIM card to use a mobile phone with all the expenses charged to the original SIM’s owner.

By the late 1990s, Germany and other European countries had been liberalising the telecommunications industry, personal computers had become commonplace and many people connected to the internet from home. “There was the terminology of those days, with the ‘information highways’ and ‘information society’ and so on, and that was the time we became invited also to governmental hearings because we had clearly established ourselves as an entity that explained to journalists the whole day how things were. (…) And we used what Wau would later call ‘the power of definition’”, says Andy, who by 1996 had even spoken at the European Parliament.

In such a complex and quickly-developing field with few public experts, the security industry and commercial interests had an edge when it came to lobbying for public policy about infrastructure and regulation. “Politicians, it took them a good 20-25 years to start to understand what the computer phenomenon means for society. And some still don’t”, Klaus says. Thanks to the CCC hackers’ public profile and ability to explain clearly concepts most people didn’t know anything about, the Club was able to play a role and bring individual rights and the public interest to the political discussion – at least in their home base in Germany.

“The Wau Holland Foundation is the dumpsite for old hackers that promote non-popular ideas to the young people”, jokes Klaus.

In 2001, Wau died of complications caused by a stroke. In his last years, the CCC’s founding figure had been teaching computer technology to kids in a youth centre. After Wau’s death, his family and friends established the Wau Holland Foundation (WHF) to support and fund projects aligned with Wau’s –and the CCC’s– philosophy: freedom of information, right to privacy, and people’s informational autonomy.

Today, both Andy and Klaus, along with three other veteran hackers, sit on the board of the Foundation, which has remained loosely connected with the CCC. “The Wau Holland Foundation is the dumpsite for old hackers that promote non-popular ideas to the young people”, jokes Klaus, who is actually the WHF vice-president.

“We are kind of the old boys’ club in the game”, agrees Andy. “(And) we are used to not taking ourselves extremely seriously, that comes from Wau’s spirit”.

Security interests and commercialisation

During the 2000s, in the eyes of the CCC hackers, the internet was moving away from its original potential to become a decentralised network that people could use to communicate on equal terms and to demand transparency from governments. Instead, the internet was becoming a space closely watched by security agencies. “(But we made people) aware that in technology security just doesn’t exist”, Andy says. “Security, from a sociological point of view, can be defined as the feeling of security. (…) And governmental acting in the field and even police work in the field of security often are still addressing this security feeling of the citizen. (…) Of course, that’s all highly political and that was our language, as we were seeing this as a political act”.

It was also during this period when corporations went from occasionally circumstantial allies of the hackers –as companies too wanted a liberalised and open internet– to aggressively trying to impose their own commercial services on the web. “We were, I wouldn’t say having a blind spot, but we were underestimating what the commercial bias would turn (the internet) into”, Andy says about that period. “To provide access to wider parts of the population went hand in hand also with a consumerish attitude of the corporations”.

The development during the 2000s of the so-called Web 2.0, which facilitated and promoted user-generated content, culminated in the rise of social media and, along with the generalisation of touchscreen smartphones able to track their users’ habits and movements, completed the kind of ubiquitous internet we have today. “In retrospective, we had a very positive view and attitude towards what technology would positively be able to do to change society to make things more transparent. So we didn’t forecast Facebook on those days, to say it brutally”, Andy says. “This was about the idea of systems that would allow citizens to challenge those in power and to better understand governmental procedures, to deal with the power of corporations in a totally different way by being better informed about the reasons and the process how governments make decisions, and to intervene more with those processes”.

“In retrospective, we had a very positive view and attitude towards what technology would positively be able to do to change society to make things more transparent. So we didn’t forecast Facebook on those days, to say it brutally”, Andy says.

But this same generalisation of computers and the internet helped the CCC grow. More local chapters had been opening around Germany and the Club became what it is today: a decentralised collective of hackers still wanting to believe in the potential of computers for good, and acting as a sort of citizen watchdog on the abuses of IT by both governments and corporations.

Defending democracy

In 2007, the German Interior Ministry announced it had developed a Trojan –a program that can infect computers and steal information from them– to spy on computers of terrorism suspects. The government wouldn’t need court approval to use the Trojan, which would be able to record audio and images from inside the person’s home, according to a draft of the law the CCC got hold of. The hackers said this kind of surveillance hadn’t existed in Germany since the Stasi, the East German secret police.

In a ruling welcomed by the CCC, in February 2008 the Constitutional Court said the fundamental right to privacy extended to people’s use of computers and the internet, and that the government could only spy on someone’s computer after a court approval and under strict conditions and indications of a concrete danger. “I don’t want to go back to the feeling that I remember from East Germany, it felt like a surveillance state”, says Constanze Kurz, 43, a computer scientist who grew up in East Berlin, and for whom today’s surveillance may be even more pervasive. “I was a child back then and I knew what I couldn’t say in school. And that’s not the way it is today, because you don’t have the feeling that somebody is watching over your shoulder when (you hold) your phone, but they do”.

Constanze, who once hacked her own car (a German smart), is the one female spokesperson for the CCC, and one of a clear minority of women in the Congress. “In the beginning, everybody asked me whose girlfriend I was”, she laughs remembering when she joined the CCC in her early 20s. “(But) it’s getting better in the hacking community”.

Constanze is part of the Club’s biometrics team, which for years has been researching and advocating against the collection and use of biometrics data, both as an invasion of people’s privacy and for practical reasons. When in 2007 the government announced a new passport that would include the person’s fingerprint, the CCC distributed a slide with Interior minister Wolfgang Schäuble’s fingerprint in its magazine. The Club had got the original print from a glass of water Schäuble had touched during a panel discussion, and then the hackers in the biometrics team had been able to reproduce his fingerprint by using everyday means.

In that same year of 2007, the CCC published a long report detailing how electronic voting machines –used massively for the first time in Germany in the 2005 elections– could be tampered with: the hackers had been able to break into the machines and reprogramme them to play chess. More prosaically, they also showed the votes themselves could be manipulated. Feats like these made the hackers’ popularity grow, and by the end of 2007, the number of Club members had reportedly increased by 33%.

“In the beginning, everybody asked me whose girlfriend I was”, she laughs remembering when she joined the CCC in her early 20s. “(But) it’s getting better in the hacking community”.

Then, in early 2009 the Constitutional Court mentioned the CCC’s work when it ruled the government should stop using those voting machines. The Court said the voting process ought to be understood in its entirety by people without any kind of technical knowledge. As the CCC had argued, the voting machines were “black boxes” of which the inner workings were hidden to the users – in this case, people casting their ballots.

“The Club is known not only for a political view but also for a very distinguished technical expertise”, Linus says. “And our political principles are transparent, and our technological expertise is subject to the scrutiny of any other expert”.

Or as Constanze also puts it: “If you want to know if a voting computer can be hacked, then it’s quite good to have a hacker to look at it. And also to have expertise from somebody who is not paid from anybody, or affiliated with the (political) parties. Because most experts are affiliated with somebody, or it’s a lobby organisation or depends on money. And we don’t”.

Beyond Germany

Since the 2000s, Congress has been becoming more international, with speakers, hackers, and visitors coming from all over Europe, and some from further away. Quite a few talks now are in English and not only in German, and all talks have a live translation into other languages.

In the last years, the Club has kept making international headlines over its revelations about very well known tech products. If in September 2013 the hackers showed how to fool Apple’s fingerprint recognition system on the iPhone 5s, then in 2017 they did the same about Samsung’s iris recognition system in the Galaxy 8.

This all has been giving the CCC more recognition beyond Germany. “But (our) political work is mostly German and some European. We travel to Brussels sometimes but it’s not that often, because it overstretches our abilities”, Constanze says. “It’s non-profit unpaid work what we do (as the CCC), we all have jobs and have to work”.

In a time of so-called “fake news” and pervasive propaganda, and when people’s attention and personal data are being monetised by social media companies, the CCC also has a project called Chaos Goes to School.

The Club’s public engagement goes beyond publicising IT vulnerabilities and trying to enlighten politicians, journalists and the general public about the possibilities and dangers of computer technology. In a time of so-called “fake news” and pervasive propaganda, and when people’s attention and personal data are being monetised by social media companies, the CCC also has a project called Chaos Goes to School. It’s aimed at improving children’s media and IT literacy, so that they can responsibly control computers and the internet and not the other way around. The Club also reaches out to parents and teachers, and advocates for introducing digital technologies as interdisciplinary topics. For instance, teaching how GPS works in the Geography course, net neutrality in Social Studies or Economics, and translation software in Foreign Language.

Decentralised meritocracy

These days the CCC has more than 10,000 registered members scattered around 30 local chapters, including a few in Austria and German-speaking Switzerland. The Club itself exists through these local branches, which function in an autonomous way, have their own hackerspaces for people to meet and hack, and produce podcasts and engage with their local communities and authorities in different ways.

Local chapters’ representatives meet regularly to discuss the projects each one is working on, and every two years there’s a general assembly where the hackers take CCC-wide decisions and plan big events like this Congress.

There are also what the CCC calls Chaos Meetings, which are casual and informal gatherings of people who feel connected to the Club’s ethos and way of doing things. These meetings may become regular happenings, and then the people organising them can apply to the plenary to become a registered CCC local chapter.

People can become associated with the CCC just by attending a Chaos Meeting and then participating in a local chapter. And at some point, they can become officially registered members by paying a small annual fee that goes to cover the infrastructure and functioning of the Club itself.

The way everything works in quite organic and, depending on their interests and willingness to share their time, participants and members may end up gravitating towards the team of CCC hackers working on biometrics, or voting machines, or the government Trojan, or Chaos Goes to School or any of the other Club’s projects. If one starts volunteering to do things and does them well, then that person starts getting more responsibilities in that area and may become part of a team and even end up leading the work themselves. “People are surprised at how this works: the structures of the CCC are meritocratic”, nexus says.

For such a decentralised organisation, when it comes to speaking publicly on the Club’s behalf it’s only those recognised as official spokespeople who can do it, and now these are nexus, Linus and Constanze, and also Frank Rieger, 47, an IT security expert and author.

The whole Congress is organised in that way, nexus explains. If someone wants to contribute two hours of their time, that’s fine; but if they are willing to give more time and work well, then the may end up being responsible for a whole area of the Congress organisation. “People are deciding what they want to do on their own. If I stand up and I don’t want to talk to the press anymore, I just say that and go. (…) Then, of course, I don’t get to speak to the press again, only maybe if I do some work again and get to the same position again”.

For such a decentralised organisation, when it comes to speaking publicly on the Club’s behalf it’s only those recognised as official spokespeople who can do it, and now these are nexus, Linus and Constanze, and also Frank Rieger, 47, an IT security expert and author. Other people approached during the Congress just refuse to speak to journalists, or if anything they only give some vague answers and then decline to give their name.

People here care very much about their privacy, and part of the appeal of the Congress for CCC members, hackers, sympathisers and other visitors is to enjoy their freedom in an environment that aims to respect the values the Club stands for. “(For the) last years there has been a sign, ‘Be excellent to each other’. And this is how we work: we are excellent to each other”, nexus says. “Every person out there is special in a specific way, and that makes us different, and that makes us individuals. And you cannot be an individual everywhere out there. Some people here, when they are going to work they wear their suits and are sitting at the desk, and that is not what they want to be, and here they can be what they want to be. And that is something we find of high value. And it is an expression of the freedom we want to distribute in the society”.

***

Jose Miguel Calatayud is a freelance journalist currently based in Barcelona. In 2017 and 2018, he researched citizen political engagement and democracy in Europe thanks to an Open Society Fellowship. Earlier, he has been based in East Africa and in Turkey as a foreign correspondent. He has reported from three continents and his work has appeared, among others, in El País (Spain), the New Statesman (UK), The Independent (UK), Agence France-Presse, Radio France Internationale, Deutsche Welle (Germany), GlobalPost (US), Al Jazeera (international), Internazionale (Italy), Information (Denmark) and Expresso (Portugal).

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)