Childhood

As a child, I wanted to become either a clown or a journalist. After all, both professions are considered equally eccentric in Krasnodar, the city where I was born. I’m 23.

My mum is a pharmacist, and when I was little, my dad worked in the bailiff’s office. Until second grade, I spent much of my time with my father at work. We spent whole days playing Counter-Strike with the guys in his office — it seemed like everybody in the office logged on. I guess I really was my father’s daughter. I dressed like a boy, behaved like a boy, and fought like a boy — I could hold my own against the boys, too. My voice was pretty low. At one point, my fifth grade teacher even called me up before the whole class. “Look, girls — don’t be like Nenasheva. If you do, you’ll never become women.” she said. “I can’t fathom how she’ll have kids at all, look at how austere she is. She’s nothing like a girl at all!”

I simply understood that the world was against me, and that I had to reckon with it — to fight it.

I never told my parents about that episode. I simply understood that the world was against me, and that I had to reckon with it — to fight it. That’s when my problems began with the older girls. I was walking around our district, and a group of them, perhaps four years older, pointed at me and laughed, shouting some shitty abuse. I could have just gritted my teeth and walked on, but I didn’t. I answered back. They got mad, insulted me back, and then started to bully me constantly. They would wait for me around the corners and threaten me. And since we had all grown up in one area, the threats lasted until those girls finished ninth grade and wound up somewhere else. In total, the whole trial lasted for more than three years.

There was a constant need for me to defend myself, to find a way out — I felt it with every fibre of my body. And thanks to that need, I became engrossed in books and literature. I even went on to win a bunch of city and regional literary competitions.

I started hearing stories about the lives of single mothers who slaved away for 15 hours a day, surviving on a salary of 12,000 roubles.

I was first detained at the age of 13. We had a fountain in the centre of town which for some reason was called “the prostitute”. My friends and I would sometimes hang around it, me with my literature textbooks. Some police officers approached us and began to ask questions, very brusque, very sharp. What were we doing there, were we stoned or something. My friends dutifully answered, while I was struck by some kind of teenage arrogance. I decided that I would say nothing, since they were being too aggressive. They asked me why I wouldn’t turn to face them and have a chat. So then they took me to the police station without any of my friends. For a few weeks afterwards, rumours circulated around school that “Nenasheva was detained!” and so forth. I went on to be detained another four times for the same disobedience.

I first ran into the troubles of adult life when I turned 14. I found a job as a dishwasher and chef’s assistant, where I stayed for three years. In that kitchen, I started hearing stories about the lives of single mothers who slaved away for 15 hours a day, surviving on a salary of 12,000 roubles.

Censorship

Once I finished school, the time had come for the major literary competition which would guarantee the winner a place to study at Krasnodar’s leading faculty of journalism. As I was the favourite to win the forthcoming contest, I had already found a great topic to write about.

In the centre of our city there’s a cemetery where soldiers from the Second World War are buried. Nobody had really looked after the gravestones since the 1990s: they were covered in dirt, sinking into a bog of some kind. A friend and I headed out to the cemetery; I had asked her to take photographs. Just then, we saw a guy masturbating in front of a soldier’s grave. After that, my friend and I didn’t speak for three or four days. And I couldn’t bear looking at men. I was already 16, but I wasn’t in a relationship. I didn’t go to parties and led my own lifestyle. What shocked me the most wasn’t that he was masturbating, but that he was doing it beside a grave. I didn’t even know there were people who weren’t even necrophiliacs, but simply got off on graves, on death. And for a very long time, I had no idea how to process that experience.

I began to write letters — including to Krasnodar regional governor Alexander Tkachev. And then I decided that I would write about him, the guy at the cemetery, for the competition. Retelling that event became a process of reflection.

I wound up in last place. Before that, I’d only won — or nearly won — those city competitions. I’d only received prizes. The winner, I recall, was some girl who’d written about the Krasnodar school of dance. It turned out that at our faculty of journalism, it just wasn’t done to criticise the authorities in the slightest. That’s the first time I encountered censorship.

Nevertheless, thanks to that experience I decided to aim my sights for the literary institute in Moscow. And I got in.

Zavtra

I moved to Moscow in 2012. I was 18, and spent a long time looking for a place for myself in the institute and the city. I soon realised that I was bored of drinking with the crowd at the student dormitory, and decided to find work.

I handed out CVs by the dozen until miraculously, the Moscow Union of Writers agreed to hire me. You must understand that for people from the provinces, the capital’s Union of Writers is something of a sacred institution. So imagine my surprise when I first arrived at work to encounter two very peculiar secretaries, neither of whom appeared to have any relationship to art nor to literature. There were also two managers with small salaries, presiding over an old mansion. The work of their secretaries was to smile sweetly at the writers who came to them, take their manuscripts and promise to do something. The secretaries would then throw the writers’ work on a pile to be forgotten about and bitch about them behind their back. One of them, who always sported knee-high boots, stayed for just two months before she cleaned out the cash register and fucked off.

My work consisted entirely of ringing up members of the Union of Writers and offering them to be featured on that year’s calendar for 10,000 roubles. It was absurd work, as it quickly turned out that about 80% of the union’s members had already died. Another ten percent hadn’t written anything in ages. Of the remaining ten percent, only half considered it a great success to have their photos appear on the calendar. I was dying with laughter as I continued to send out my CV.

I saw it simply as a newspaper which had agreed to publish my article about the closure of my favourite museum.

The newspaper Zavtra eventually responded. Now I know they are red-brown ultra-nationalists — I suppose you could call them “Orthodox Stalinists”. But back then, I saw it simply as a newspaper which had agreed to publish my article about the closure of my favourite museum, the Vladimir Mayakovsky museum at the Lubyanka. They agreed, despite the fact that I attacked Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin in my article. After that I visited all the exhibitions there were to visit. I sent my reflections to Zavtra, who always published them without any censorship. I knew that more established reporters weren’t thrilled with my work, but what did I care? During the first months of my work with the paper, I didn’t participate in the editorial meetings, but communicated directly with my editor, who gave me complete freedom — and happened to be the son of editor-in-chief Alexander Prokhanov.

Then one day, they sent me to a protest at Bolotnaya Square. My editors didn’t give me any particular angle or worldview to stick to — but simply asked me to write a report. I was in shock when I arrived at the square — I had never attended such big events before. The crowd frightened me. Still, I began to approach people, asking their names and why they had turned up. Most said they had come by accident and didn’t understand what was going on, but they held placards because their friends had asked them to. Everybody seemed to repeat the same lines, like zombies. I saw a circus, and I described it as such in my article.

It still pains me to think about what I wrote.

Now I understand that this was Bolotnaya in 2013. The first arrests and searches had taken place, people had been fired for attending protests, and unlike me, my interlocutors understood the reputation of Zavtra and probably saw me as an enemy. But at that moment, I didn’t know a thing about demonstrations, and had no friends in opposition circles. I was just shocked by the whole event, and produced a pretty devastating report about the rally. It still pains me to think about what I wrote.

War

Then the war in the Donbas broke out. But the sense of being subject to propaganda didn’t come quickly.

I was still writing about art and some non-political, social issues. At first, my editors started asking me to take quotes from some strange guys — historians, for example. Then they requested a profile of the governor of Crimea — an ordinary biography, based on open sources. Then I noticed that the older reporters, with whom I’d been at loggerheads, started to vent their rage at opposition circles without any basis in fact or coherent argument — not only in conversation, but now in their texts. Before long, open calls to armed conflict were appearing in the newspaper. But not in my own pieces, I simply couldn’t do that — despite the fact that I had a grandfather living in the Donbas.

At that point I realised just how little I noticed how our daily work helped fan the flames of war.

Once, I was sent to interview some girl called Lena. Her husband had just died somewhere in the fighting. She was a teacher — he was an ex-con, who’d gone out one day to figure out what was going on. He and his friends had arrived in Luhansk, and ran into trouble literally two days later. I recall how we sat among his belongings in that apartment where he and his friends and hung out just a week earlier and drank wine. Lena described to me how she tried to identify her husband’s corpse by his tattoo — his face was unrecognisable. At that point I realised just how little I noticed how our daily work helped fan the flames of war. Even my innocuous text about the governor of Crimea played its part in kindling a conflict. I felt that my texts might also be responsible for what was happening and in their own way, for the death of Lena’s husband.

After that, I quit. Upon leaving, I asked my colleagues to delete my surname from all texts which bore it on Zavtra’s website. I was ashamed.

Charity

I attempted to get an internship at the Agency for Social Information and Snobmagazine. Neither took me on.

I eventually found a vacancy as a supervisor at the Mercy foundation, an Orthodox Christian centre for children with developmental difficulties. During the interview, I was asked what church I go to when fasting ends, and some further questions about biblical symbolism. I’m baptised, but hardly a churchgoer.

I confessed that I was sleeping with my boyfriend, and repented for the sin. But the priest simply kicked me out of the confession.

So they suggested that I fast and start attending services — to become a practising Christian, so to speak. I reacted with some enthusiasm. I even worried when I ate communion bread without the proper sacraments. Then I went to confession for the first time and fasted before communion — it was a big event for me. But then unexpectedly, the experience became hellish. I confessed that I was sleeping with my boyfriend, and repented for the sin. But the priest simply kicked me out of the confession. That was really unexpected. I was so disappointed that I never returned to that church — and have never attended confession since.

Nevertheless, I soon found work for another charitable foundation — this time, one not under church control. One of their programmes was called “I’m waiting for you, mum!” They drove the children of female prisoners to their mothers. That’s when I first set eyes on a prison colony — it was located in Vladimir Oblast, designated IK-1.

At IK-1 I met Lyuba, who begged me to take a portrait photo of her. As nobody had photographed Lyuba for five years, none of her relatives knew what she looked like these days. For some reason, the administration of the prison colony were categorically opposed. Instead, Lyuba was sent to the prison kitchen to bake pies for us. The atmosphere there was like in any other large kitchen — women in aprons kneaded dough, everywhere was covered with baking trays and huge oily pies filled with jam. I asked the women why they weren’t going to eat pie with us. They answered that they were forbidden from sweet foods.

And that kitchen became this kind of separating line, the border between freedom and unfreedom for a person. When freedom is nothing more than a pie and a photograph. That’s when I thought up my first protest performance.

Action

I thought: “OK, if you can’t have your photograph taken, then I’ll take on the image of a prisoner. And I will wear prison clothes for a month on the streets of Moscow, watch for people’s reactions. Let my body become a symbol of your collective bodies, your pain, your loneliness. I will take my own photograph everywhere I can and send those images back to the prison.”

I should say that I already had quite a bit of experience with public actions — I dreamt of becoming a clown. I was involved in KVN, the student comedy show, practised my singing and acting in school groups. In Moscow, I was in a poetry group “But” with my friend, the poet Gleb Osipov. We carried out all sorts of performances. We organised exhibitions in abandoned houses with Denis Semenov, the artist.

Cops joked that it would have been better for us to perform in Bitsevsky Park — they would have got us instantly there.

We visited the prison in April 2015, and I was already performing for the first time in June. 12 June is Russia Day. It seemed important to me to go out onto Bolotnaya Square in my get-up and sew a tricolour from red, white and blue pieces of fabric. Nadezhda Tolokonnikova from Pussy Riot joined me. We had only just put our chairs down and starting getting ready when the cops turned up. They joked that it would have been better for us to perform in Bitsevsky Park — they would have got us instantly there. And so they detained us.

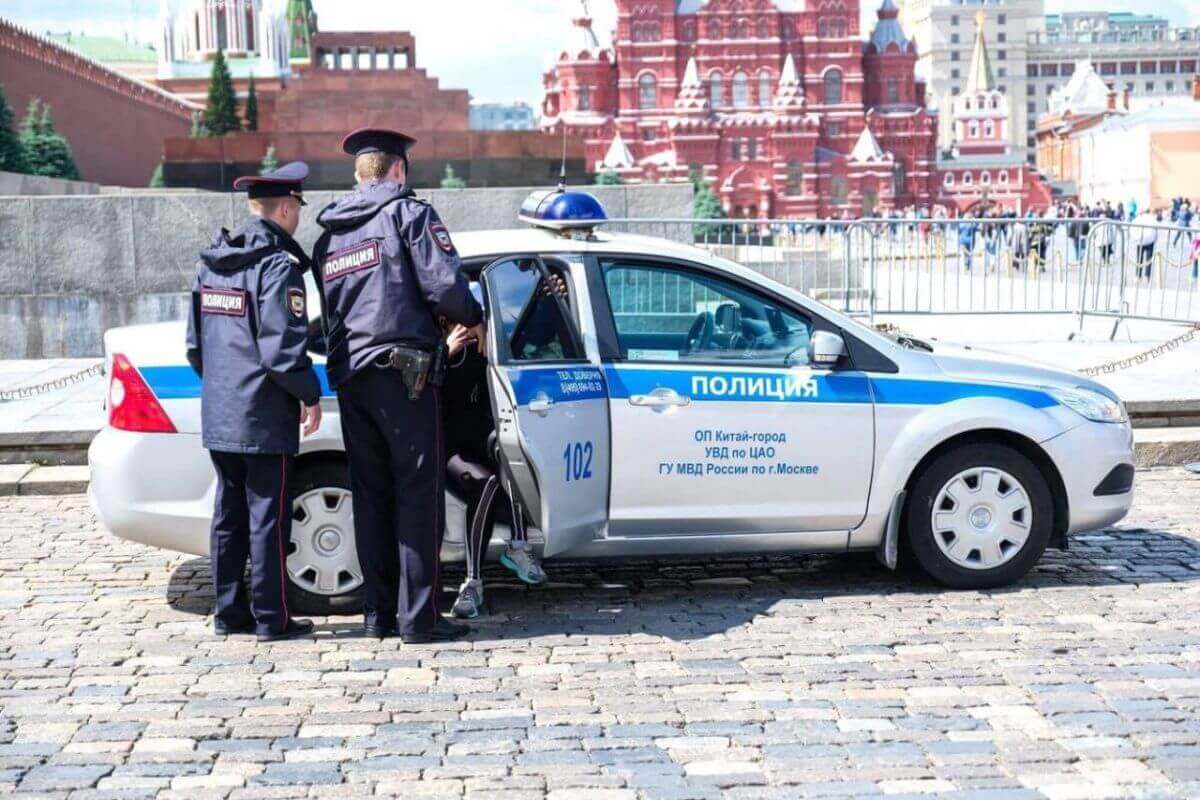

That was my first detention for actionism. I was surprised at how quickly and easily it happened, and the kind of helplessness you feel when the doors of the police station close behind you. I was super lucky that I was with Nadezhda. She taught me how to talk to the cops: for instance, to mention Article 51 of the Constitution, which means I have the right not to give evidence against myself, to call a lawyer and to the prosecutor’s office. They let us go after three hours, without pressing any charges.

Over the month that I spent in the prison uniform, some people reacted aggressively, pushing or insulting me, and some asked questions about prison life — both on the streets and even in the police station. And everyone for some reason was sure that female prisoners have to be bald, that they have their heads shaved.

So on my final day of the action, I decided to ceremoniously remove my uniform on Red Square and at the same time shave my head. And the police detained me once again. And my friend who’d come to shave me. The court accused us of holding an unsanctioned public meeting and put us in jail for three days. The funniest thing is that the police report had some surreal details in it — apparently, my friend was shaving me with a musical instrument. They didn’t even return the shaver in the end.

So it’s just like the Soviet times, everyone in Russia lives by the principle “don’t stand out”.

This really annoyed the director of the charity where I was working. He wanted to fire me, but he changed his mind.

The next detention was in Autumn 2015, when we were washing a soldier’s uniform that was cover in the blood of our Ukrainian friends on Konyushennaya Square in St Petersburg. That was on 4 November, the Day of National Unity. They didn’t even bother drawing up a report.

What struck me most of all was the fact that everyone went into the police van voluntarily, no one even tried to resist. No one, including me.

Then there was the arrest in March 2016 for the “No peace” exhibition in Moscow. Artists, political activists brought their work that symbolised the events in Ukraine. We wanted to walk through Moscow and watch people’s reaction. I love to use the street as an artistic instrument. We planned to start with Kursk metro station, but when we got there, the police vans were waiting for us. We tried to hide at Vinzavod, but the security guards chased us away. And so when we left, we were arrested. What struck me most of all was the fact that everyone went into the police van voluntarily, no one even tried to resist. No one, including me.

At the police station, they demanded we hand over our works, otherwise they threatened us with 48 hours of jail. We handed them over, but printed out photos of them and handed them out when we had to go to court. And outside the court, the artists organised a flashmob, choosing to draw the court building en masse.

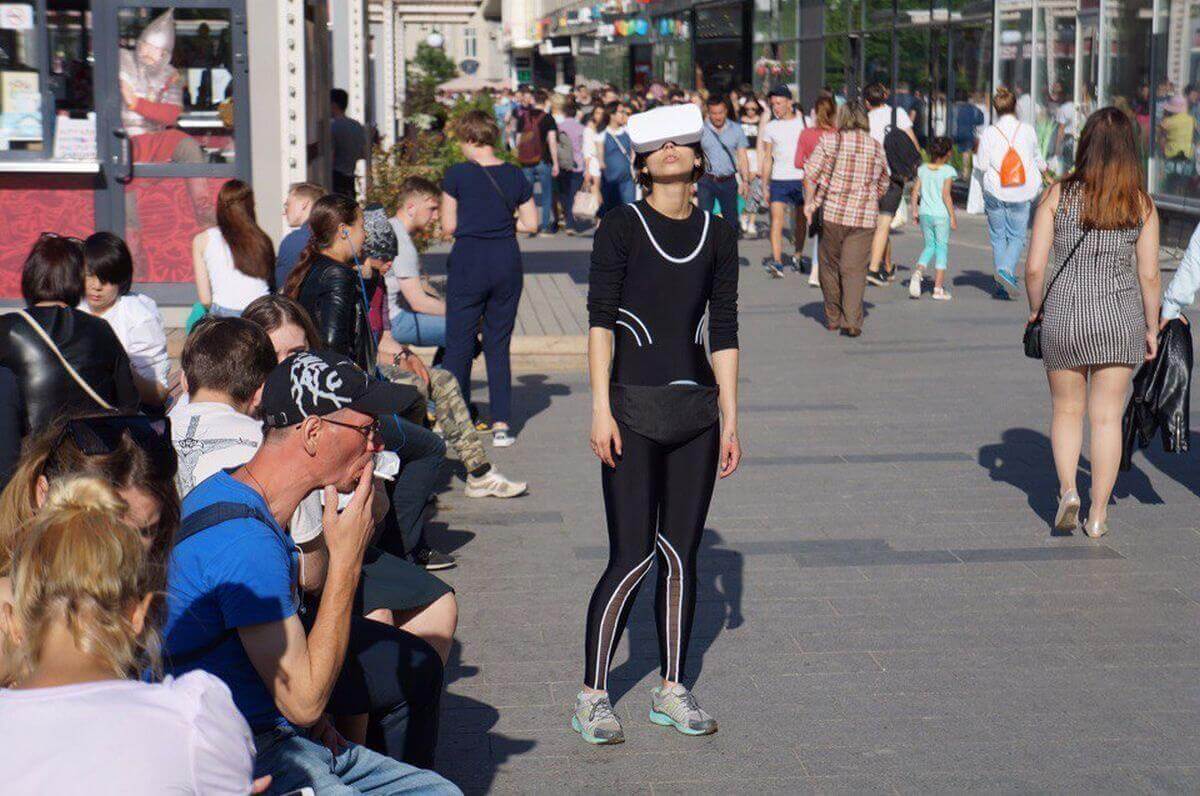

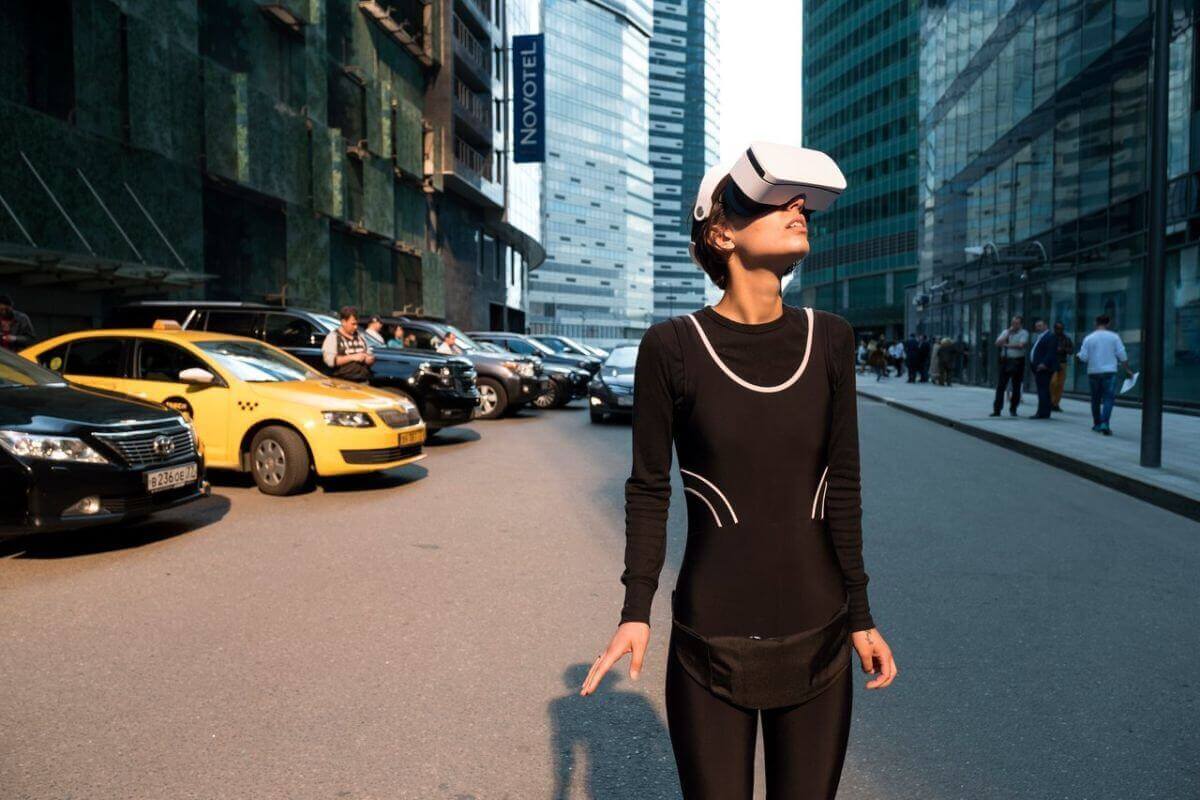

The final time was in June. I was walking around Moscow wearing VR goggles, to compare what I was seeing in reality with what people locked up in psychiatric shelters see. There’s more than 150,000 people locked in these shelters in Russia, and their living conditions are significantly worse than prison. I walked around Red Square in these goggles on 22 June, and I was detained, of course.

Today, any person who looks kind of different attracts the attention of the police. So it’s just like the Soviet times, everyone in Russia lives by the principle “don’t stand out!”

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.

This article is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. If you have any queries about republishing please contact us. Please check individual images for licensing details.