In late January, news that Viktor Filinkov, a left-wing activist and computer programmer, had disappeared (24 January) at St Petersburg’s Pulkovo airport was followed by arrests and searches (26 January) at the apartments of anti-fascist activists in the city. When Filinkov then surfaced in court and pre-trial detention, he stated he had been tortured by officers of Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) – as did a witness in the case, Ilya Kapustin. Another Petersburg anti-fascist, Igor Shishkin, also disappeared after his apartment was searched.

As it turns out, the Penza branch of the FSB opened an investigation into a “terrorist organisation” (Section Two of Article 205.4 of Russia’s Criminal Code) in October 2017. Here, Egor Zorin, Ilya Shakursky, Vasily Kuksov, Dmitry Pchelintsev, Andrey Chernov and Arman Sagynbayev (arrested in Petersburg and transported back) were arrested within a month. According to investigators, all the arrested men were members of the Set’ (‘Network’) organisation and were planning to use bombs to provoke “popular masses for further destabilisation of the political climate in the country” during the presidential elections and the football World Cup, thus organising an armed uprising. The network’s cells were allegedly operating in Moscow, St Petersburg, Penza and Belarus.

Russian security services have accused Filinkov of being a member of this same terrorist organisation. In detention, Filinkov described everything that had happened to him after he was detained at Pulkovo airport on 23 January 2018 and until his arrest by a city district court. Below, Filinkov describes how he was medically examined before he was subjected to electric shock torture, interrogations at the FSB and endless conversations with bored agents. He sent the following text to members of the city’s Public Monitoring Commission (ONK), which monitor human rights in detention centres.

Other suspects in this alleged terrorist organisation – Ilya Shakursky and Dmitry Pchelintsev, and Ilya Kapustin, the witness detained in St Petersburg – have also provided detailed testimonies of torture. Pchelintsev and Shakursky said that FSB agents tortured them with electric shocks in the basement of Penza’s detention centre. Igor Shishkin, the anti-fascist who also disappeared in Petersburg, did not mention torture, but doctors documented that the interior wall of his eye socket was broken, and that he had multiple bruises and abrasions; members of the ONK who visited him in detention documented multiple marks on his body that resembled electricity burns.

The first meeting with FSB agents: “Is it SS or VV?”

My detention began on 23 January 2018 at boarding gate A08 at Pulkovo Airport. My flight was at 20:05. Several men in plain clothes were wandering around the waiting area for half an hour before – it was obvious they were not flying anywhere.

I was surrounded by five-six men, a middle-aged man in a pink checked shirt was standing in front of me. He opened up an ID in a brown cover and introduced himself: “FSB Major Karpov [I am not sure about the surname, I could not see anything in his ID], come with us.” I was surprised, asked what the matter was. I heard behind my back: “Take his phone!” “Give me your phone, follow us!” said the man in the checked shirt. I complied, pulled out my headphones and gave him my smartphone. “All phones!” I heard again behind my back. “Alright, we’ll sort that later.” Karpov was the only FSB agent who introduced himself.

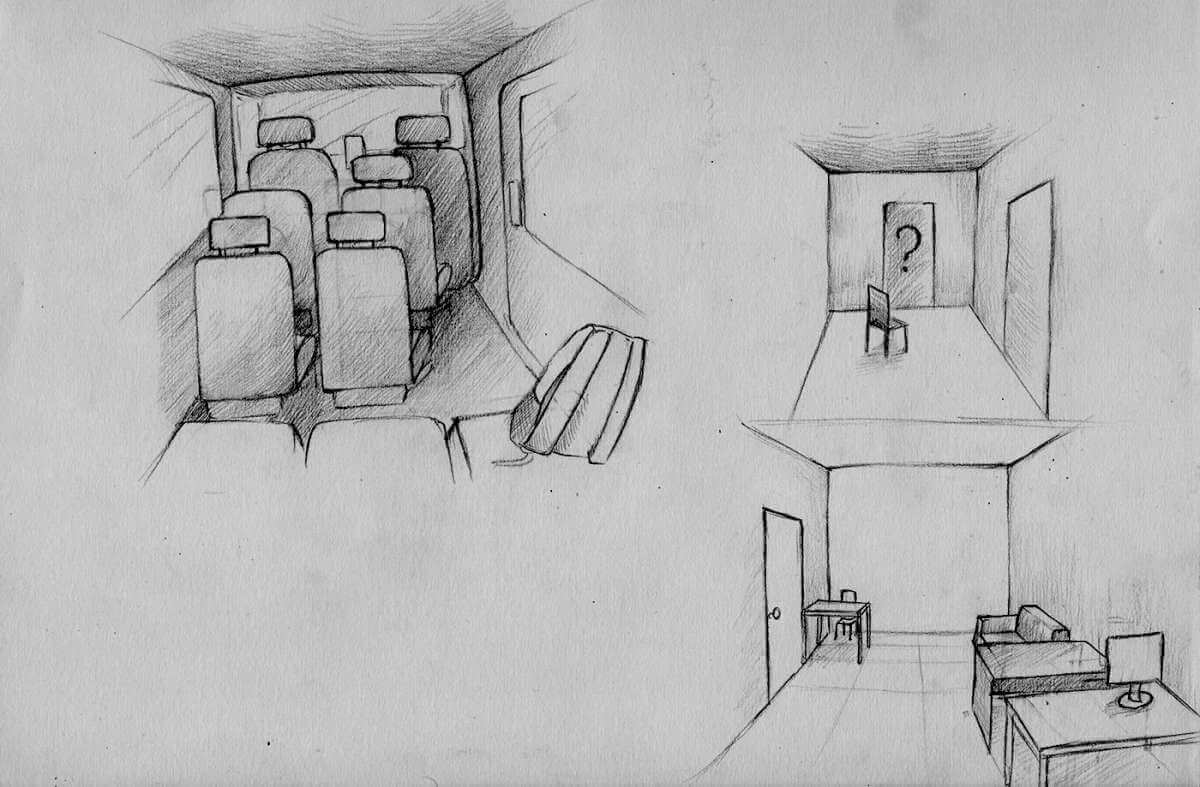

They brought me to a room, which you could only gain access to via a special pass. There were a server box, a cabinet, a device I didn’t recognise the size of a cash machine, a table with chairs, a leather couch and a cupboard. They put my stuff on top of the cabinet, and asked me to sit down on the couch. I looked at the wall clocks: it was approximately 19:35. Around an hour later, the first couple of agents arrived. They asked many questions, including about my salary. I even thought they were going to demand a bribe.

After another hour, two more agents came. “So, Vitya, have you already realised why what is happening to you is happening?” one of them asked. I answered: “I don’t understand. What’s happening?” I had already asked this question several times, and earlier they replied that this was a simple check, that the flight was going to be delayed and so on.

“Another guy also didn’t understand, then he fell down once and understood everything.”

“Are you threatening me?”

“No, just telling you how it happens sometimes.”

At that moment, I’d already unlocked my smartphone for the agents (without showing the password), but refused to unlock my laptop, because it was my work-laptop and there was an original code on it, worth millions of dollars. There was a CCTV camera in the room, I don’t know whether it was working. They told me to get my stuff out of my rucksack. Among other things, there was a photo of my wife with some friends, one of whom was in a police hat. “Who is that? Is he a policeman or what?” they asked, going through my things. They turned on my mobile phone, started looking through texts, calls and contacts. They took my passport, Kazakh ID [Filinkov is a citizen of Kazakhstan], and tickets. They didn’t return my documents. I had to carry my stuff around until the search. They also investigated my smartphone, asked about pictures, and also took pictures with their own smartphones, holding the cameras to the display of my smartphone.

The man – the tall one, who was seated to the right from me – was rumpling something in his hands […] That made me nervous.

This was mainly done by the first pair [of agents]. From the mouth of Bondarev K.A., I heard the surname Isayev. That this man was actually Bondarev K.A., I learned only on 29 January. I had to give my charger to one of those men. They returned the charger block, but I don’t remember if they returned the cable. They put my things back into the rucksack and brought me to the airport police department, entering with their own electronic ID. A police officer came from another room and asked everyone to introduce themselves. He was shown an ID, and then he asked the FSB agents not to enter without warning: “There are three of us here, and there’s such a crowd of you coming in. We tensed up.” They tried to check my fingerprints, but they couldn’t read the fingers: Papillon [a fingerprint scanning and recognition device] came up with red light, the search didn’t produce any results. Later, we spent 20-30 minutes collecting my luggage. Somebody (perhaps, Bondarev K.A.) helped carry it. I think he put it in a Priora. At the exit, the FSB agents who were stationed at the airport were discussing where they would go afterwards, and decided to go to McDonalds, and they didn’t leave the airport.

After leaving the airport, we turned left, and I saw a blue minivan with darkened windows. From the car, two men with masks covering their faces were approaching. One was tall, and had reinforced gloves (the pattern on the gloves resembled carbon composites – checked), the other one was short. Both were dressed in cargo trousers, coats and dark, almost black, military-type gloves. The tall one put handcuffs on me (in front, not very tightly), pushed me into the car, and started patting me down. He was told “Stop!”, and replied: “But how do I know, maybe he has a concealed blade!” The next two times he also patted me down. Then he pushed me in the second row from the back, pressed my head to my knees and told me to sit like this. Later, when I realised that he wasn’t really watching me, I looked up and turned my head around to orient myself.

We left the airport. “I’ll tell you where to go,” said an agent. I saw he had a smartphone with a map open, because there was no headrest on the seat in front of me. I tried to remember where we were driving, but quickly abandoned the effort – as it turned out later, it wasn’t necessary anyway. While we were driving, one of the agents received a call, and another agent asked: “Is it SS or VV?”.”‘SS,” answered the man who was called. The phone conversations were not lively. “Yes, all is fine, we are already on our way with Viktor.” I heard such conversations several times during the following 24 hours.

The man – the tall one, who was seated to the right from me – was rumpling something in his hands, but I couldn’t quite see what it was (but it wasn’t a taser); perhaps he was rumpling his gloves or the reinforcements on them. That made me nervous. During the first or the second trip, the tall one changed places with the short one. Otherwise, the tall one was always seating on my right side.

Police department. Medical inspection before torture

I was ordered to get out of the car. I got out; the men in masks grabbed me under my arms one of them, the shorter one, adjusted his mask (perhaps, he was driving with an open face), and they dragged me to the porch. The tall one said: “Yes, cover up, there are cameras in there.” We were passing a red plaque: “…MVD [Ministry of Internal Affairs] Krasnogvardeisky District.” Policemen (in uniform) were not surprised by the guests. I was taken into a small room with a bench, a table, a chair and a Papillon device.

A policeman (under the close watch of two or three FSB agents; there was not much room) pressed my fingers against the glass of the Papillon device, often he wasn’t satisfied with the quality, and he repeated the procedure. When he saw “Quality: 47”, he was satisfied. |Patronymic?” he asked me. “I don’t have a patronymic in my passport.” “Well, if you don’t have one, you don’t have one” the policeman agreed and pressed enter, leaving the line empty. Then, it seems, they discussed the list of countries that stopped including patronymics in passports. “But who entered his patronymic?” the policeman asked, turning to those around him. “Well, the FSB, probably,” was the answer.

We were not delayed for long, and I – in handcuffs, still closed lightly – was taken to the minivan. Somebody’s voice ordered to follow the silver Priora. While we were driving, my mobile phone was ringing in my rucksack, it had been turned on for investigation by the first pair of the FSB agents at the airport.

I was again ordered to leave and take my rucksack. It wasn’t easy to do that in handcuffs, but after leaving the car they took them off. The men in masks didn’t go into the building. There was a plaque on it: “…Hospital 26”. An ordinary hospital, everything in terrible condition. There was a queue at the registration, the agents even complained that they had to wait with everyone. Everything was sorted out by a doctor from hospital administration. He looked young, he was unshaved, medium – a bit below medium – height. They were discussing for a long time what to do with my insurance, since I am a foreign citizen and don’t have a compulsory medical insurance certificate. The FSB agents suggested I pay with my own money: “What’s the problem? Do you have a lot of money?” At the registration office, the agents said that they needed to have me “examined”.

I was asked about my complaints without waiting in the queue. I hadn’t been to a doctor for a while, I’d been waiting for insurance from my company, which I was supposed to get in February, so I had many complaints: neck, back, psoriasis, joints pain (especially my knees), headaches, and so on. The doctor noticed a bruise that already turned yellow on my right arm and asked where it was from. I didn’t remember. The agents suggested that someone had grabbed me there. They took my phone out of my rucksack, it had run out of battery from all the incoming calls. They ordered me to find the charger. I found it and one of them took it away with the phone. Then he complained that I lied to him when I said that the phone lasted a couple of weeks without charging.

I really like it how at first they all that they don’t understand anything.

Before they did a blood test, we were waiting for a doctor, and the agents were discussing something loudly, and the doctor who was sitting with us disciplined them: “I’m not disturbing you, am I?”, and later she kicked almost all of them out: “Right, you wait outside! What are you, his convoy?’” The agents talked back, but left, only one of them stayed with me. After the blood test (if I am not mistaken, three phials from a vein), my whole body was examined – probably, by a surgeon. Another agent came, he was asked to look at my tattoo and take a picture of it. After we returned to the first room, I was asked to touch my nose with closed eyes, they checked my hands, I was asked to press the doctor’s hands and so on.

We were waiting in the X-ray queue for a very long time. “More than two hours already! Why did you tell him that you have pain in your knee?” an FSB agent complained. “Who’s calling you?” an agent asked, showing me the screen of my phone. There was: “+380… 99 is calling”. “I don’t know, perhaps, my wife,” I replied. “But it’s a Ukrainian number, isn’t it?” the question, from an agent from St Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast Directorate of FSB, was rhetorical. While we were standing there, I was trying to find out what was going on.

“I really like it how at first they all that they don’t understand anything,” one of them (not Bondarev K.A.) said.

In the X-ray room, there was an X-ray machine made by Samsung that looked very futuristic. The stickers warning of the danger of laser damage to eyes, the mapping nets were all in English. One of the FSB agents (perhaps, Bondarev K.A.) went into the operating room. Almost my whole body was X-rayed: the head (profile, enface), upper body, low back, pelvis, left knee. I don’t remember the exact number of pictures, perhaps seven or 10.

“He is healthy! Nothing on the X-rays!” exclaimed an agent, as he came over with the medical documents. I wouldn’t say I was happy: after all, I was experiencing pain. They put my phone in my rucksack, and we went to the exit.

In the minivan. “Don’t move, I haven’t started yet”

Next to the minivan stood a man in mask (the tall one) He asked: “Done?” “Yes, lock him from behind,” ordered Bondarev K.A. I was surprised. The man in mask pushed me into the car: he patted me down, pressed me into the second row from behind, forced my hands behind my back and put handcuffs on me. Then he pulled my hat down my face and shouted something into my ear, forcing my head to my knees. It was very scary.

The driver was told to follow the Priora, but I don’t remember when we set off. Bondarev K.A., the driver, one or two men in masks and one or two more agents from St Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast Directorate of FSB were certainly in the car. I saw a switched-on smartphone in one of those guys’ hands (possibly Viber or WhatsApp was open). So there were at least five men in the car, apart from me.

Everything was planned in advance and didn’t cause any questions among those present.

There was no headrest at Bondarev K.A.’s seat from the first ride. Earlier I didn’t grasp the purpose of that. Now I understand that that was a special car for such “actions”, or perhaps it was prepared while I was in the airport. The one thing that was clear to me at the moment was that everything – the medical examination, headrest, handcuffs behind my back, hat on my head, men in masks – everything was planned in advance and didn’t cause any questions among those present.

It was difficult to breath, and so I decided to free my face from the hat. I started slowly nudging the hat, but managed only to free my nose, after which the man in mask pushed me to the seat with, I think, his left hand, and, I think, with his right hand punched me twice in the right side of chest, in the lower part of chest muscles. I pressed my jaws, expecting punches in the face, so that he didn’t break my teeth, but he forced me down in the initial pose with my head toward my knees. Clearly, he punched me not with a palm, the area of the punch was narrow. When he later repeated those punches in the chest, when I could see more than through the hat, I noticed that he punched with his fist, but turned his palm towards me. When he turned me into the previous position, he began to punch me in my back – also not in the centre, but to the right of my backbone. I made some noises through my teeth.

“Don’t move, I haven’t started yet,” the man in mask said. Bondarev K.A. said something like “Vitya! Vitya!” and hit me several times on the back of my head. The area of the blows was quite large and I decided that he was hitting me with the palm of his hand. His voice was right in front of me, behind the back of the seat, into which my head was pushed by those blows, and his words were synchronised with them.

I was panicking, it was very scary, I said that I didn’t understand anything, after which I received my first electric shock. Again, I was not expecting that and I was overwhelmed. It was unbearably painful, I started shouting, my body straightened. The man in mask ordered me to shut up and not to shake, I pressed against the window, and was trying to turn away my right leg, turning with my face to him. He forcefully turned me back and continued shocking me.

I was panicking, it was very scary, I said that I didn’t understand anything, after which I received my first electric shock.

He shocked my legs and then the handcuffs. Sometimes they punched me in the back and the top of the head, that felt like a clip round the ear When I was shouting, they closed my mouth, and threatened to gag it, to tape or to stop up my mouth. I didn’t want to get a gag, and tried not to shout, but it wasn’t always possible.

I gave up almost immediately, in the first ten minutes. I was shouting: “Tell me what to say, and I will say anything!” But the violence did not stop.

Their threats sounded very convincing. I believed that they would act upon them if I didn’t comply. I’ve never passed out in my life, never lost consciousness from punches in the head, only lost coordination, that is ‘I was groggy.” Once, when I was hit with a brick in my temple, I fell in a complete stupor, frozen, but was still conscious, was even falling with my eyes open and recovered quickly. I considered that an advantage of my body, but this time… I wish I could pass out from blows on my head, but that was not happening. I gave up because I was certain that otherwise I would lose my health. To be honest, I am not sure, whether my health is going to be more damaged in prison than it could have been damaged in that situation. I am feeling unwell in pre-trial detention, local doctors and nurses are unlikely to diagnose my problems and definitely are not able to help me. It’s scary to think how it is going to be in a strict-regime prison.

I don’t know whether I made the right choice, but now, when I am writing these lines, the traces [of torture] are disappearing while the state attorney and the Investigative Committee are doing nothing. The traces on my chest are gone, yesterday they counted 33 marks on my leg, six of them – pairs. Today I can discern only 27 marks. Perhaps, it was worth enduring a bit longer and attempting to leave my biological traces, also before torture, but at that moment it was difficult to think about anything at all, and in general I never thought I was going to be tortured.

There were no breaks. Just blows and questions, blows and answers, blows and threats.

They asked questions. If I didn’t know the answer, they hit me with electric shocks, if the answer didn’t correspond to their [expectations] – they hit me with shocks,. If I tried to think or formulate – I was hit with electric currents. If I forgot what they said, I was hit with currents.

There were no breaks. Just blows and questions, blows and answers, blows and threats. “You will now go naked outside in the frost, want that?”, “We’re gonna beat you in the balls with the taser” – and other threats were mainly made by Bondarev K.A. The man in mask was usually interested in the position of my body, shouts, he forced me, grabbed my neck, the scruff of my neck, arms and coat, and also punched me in my back, chest, back of the head and rarely – face, when I was trying to turn my leg away, turning my back towards the window.

In comparison to electric shocks, these ordinary blows felt weak, the punches in the head I noticed mainly when I saw whitening in my eyes. The masked man’s selection of phrases was rather restricted: “Why are you shaking? I haven’t done anything yet!” he said, when I pressed myself against the window, when he was “cracking” the shocker next to my face or my leg. That was very humiliating, I felt my complete helplessness and defencelessness. I thought if I were playing according to their rules, it wouldn’t be painful, but it was painful in any case. For some questions they didn’t have the answers themselves.

“Where are the weapons?”

“What weapons? I know nothing,” I replied, and was shocked.

“You know everything, where are the weapons?” Bondarev K.A. pressed.

“Tell me, I will say what you tell me!” I hoped for mercy, but was still shocked. After several rounds, these questions were changed for ones which there were answers.

The masked man shocked me in different places: handcuffs, neck, chest, crotch, but the most convenient place was the right leg – he pressed me against the window, fixed my body in place, pressed the taser in, pushed the button and held it like that, and I couldn’t move my leg anywhere. Bondarev K.A. repeated punches on the back of my head from time to time – all in all, he hit me at least 10 times.

I felt awful, I didn’t want them to read my messages with my wife and close friends.

“Now, you will repeat in order.” After that, there was a list of topics I had to report on. The list was long, and while it was read (not by Bondarev K.A., it was another voice, I thought), I forgot it all. “Sorry, I forgot the beginning…” I tried to explain, and they shocked me even more intensely. The threats were repeated: frost, balls.

“Why are you with your wife?” asked Bondarev K.A. “I love her!’” I shouted. “Who does she talk to?” “I don’t know!” “She is getting *******, and you don’t know?” – some questions shocked and humiliated me particularly strongly.

“Password! Password for the laptop!” [asked] one of the agents. I was trying to remember, and so got hit with electric current. “I am remembering,” I was shouting. “viktor.filinkov.***” I dictated. “In one go? One word? Bitch, we are going to check, if you are **** [lying], you’re *** [done]!” an FSB agent shouted. I felt awful, I didn’t want them to read my exchanges with my wife and close friends. I felt completely lost and doomed, I never felt so awful, I could not understand how all these people were sitting here and calmly enacting this violence.

“Hey, have you shit yourself? What’s that stink?” somebody asked. I thought there was a burning smell, the smell was indeed strong, and not particularly pleasant. I was looking at my leg, it was in dark spots, but I couldn’t understand what the spots were. I thought they were from the currents, but they were mainly on the inner side of my thigh.

The green light on the taser made me panicked and terrified, and the electric arc between the thick electrodes was, it seemed to me, lighting up the whole car.

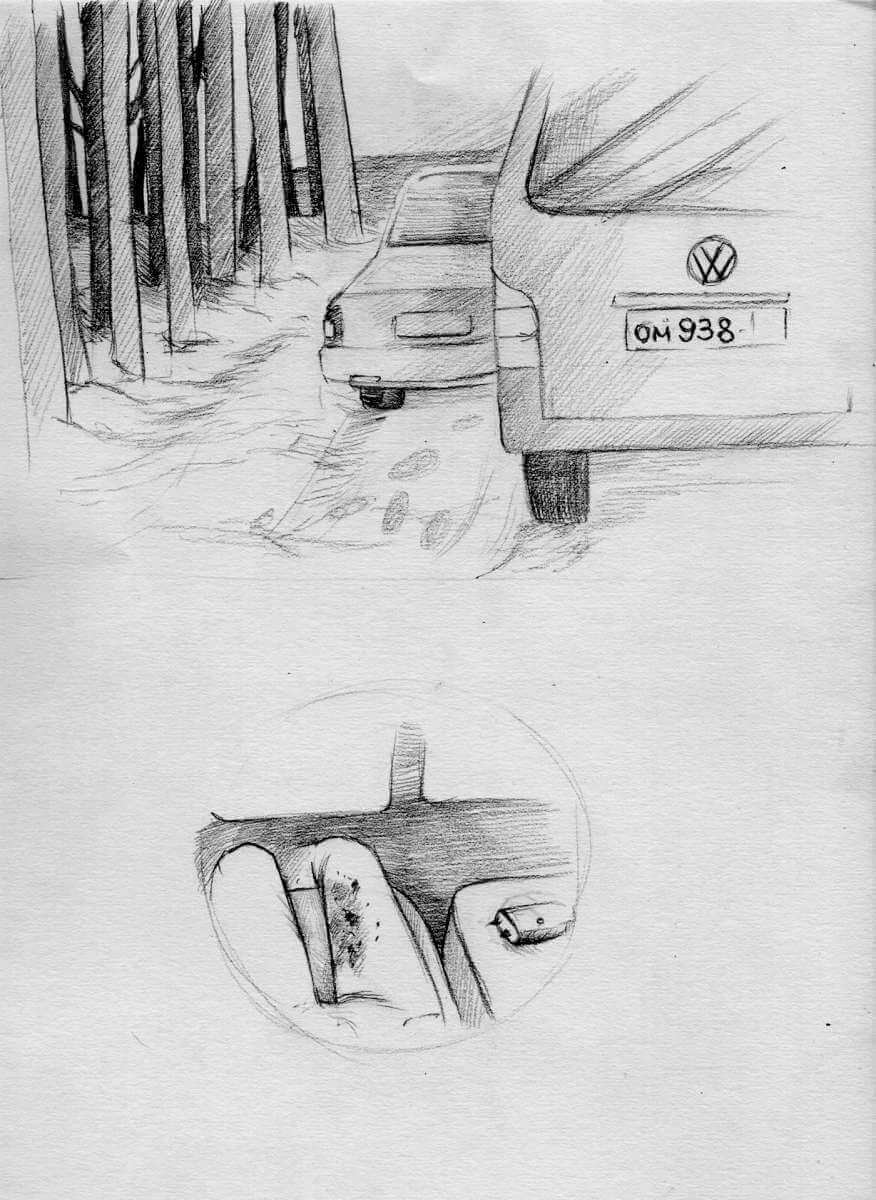

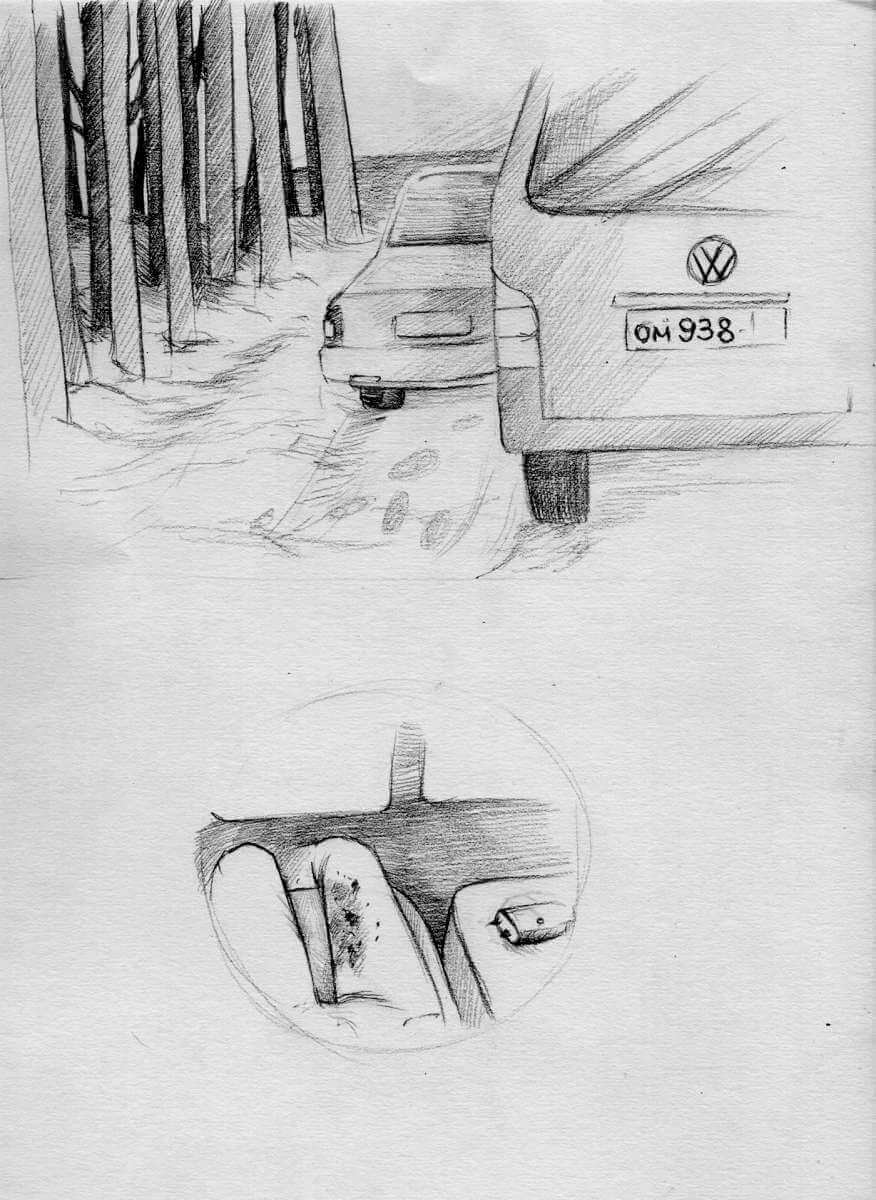

Roadside. License plate: OM 938. “Hey, now I’ll wash him with snow”

How it all ended, I don’t remember very well, but I was carried out of the minivan, and somebody noticed that my face was blooded. The man in the mask took me behind the minibus – that was the first and only time when I saw it from behind, before that I was taken up and down the side of the car. I looked right and tried to remember the number. That was very hard, my head was going to explode, my whole body was aching. OM 938, as it seems to me, was written on the plaque.

“Hey, now I’ll wash him with snow. Vitya, what happened to you, did you hit yourself? Probably when we put the breaks on!” “Yes, take his hat and clean him, leave that snow!” the agents were saying. Somebody ran to pick up snow at the side of the road. I indeed felt something on my chin. Somebody removed my hat and rubbed my face with it.

It was light, perhaps, the road was lit up. There were trees in front of me, I couldn’t see how dense they were, but it was possible to see the moon through the treetops. The silver Priora was a bit ahead, closer to the roadside, parallel to the minivan.

I was shaking, shaking very strongly: my hands and body were moving uncontrollably, the handcuffs made noises. From this moment on, I was shaking like this every time I was on the street or in a cold car. It was not connected to cold directly, I was wearing a thick coat, and it was not freezing, I think. I was just shaking very strongly: before torture and after the temporary detention centre this didn’t happen.

They took off the handcuffs, and then put them on again, lightly, in front of me. There was some trouble with the handcuffs, I don’t remember exactly, but the masked men had their own handcuffs, and they were supposed to keep them. At some point this problem was discussed, but then, from Priora, I was in the handcuffs, connected by two plates. Whether I was earlier in handcuffs with a chain, I don’t remember.

MVD Department. Blood and a snickers

We returned to the “MVD for Krasn…”, I was sitting on a bench, my rucksack was nearby. I was asked whether I eat chocolate, and what I was going to drink. I nodded and asked for water. All the agents had left apart from Bondarev K.A., who started writing up the papers. Rarely, he asked “clarifying” questions, checked what I remembered and corrected me if I made mistakes. They brought a snickers SUPER and water. My head, neck and legs hurt a lot. I ate a half of the snickers, put the other half aside on the right, it was difficult to eat, I was feeling very weak. It was difficult to talk, I felt depressed.

“He’s soaked his trousers in blood. That’s bad!” “Hey, buy him sweatpants and that’s it.” “Maybe wash it away?” I looked more attentively. Dark brown spots indeed looked like blood. Somebody threw a very small piece of wet cloth and told me to clean up. I rubbed my trousers. “What are you rubbing? Rub the big spots!” I was ordered. My half-hearted attempts to wash away the spots were in vain. “Alright, we will come up with something” an agent said, taking the cloth away from me.

“What’s the time?”

“7:30.”

Bondarev K.A. complained that he hadn’t slept for two days. “You now sign this or you will spend 24 hours driving with the same people for identification in another region of Russia. You should understand: FSB officers always get their way! It will anyway be like we decide!” Bondarev threatened me. The threat of being taken in another region of Russia was repeated once again, in one of the latest versions they added: “And a whole day back!” He wasn’t, it seems, the only person to make the threat. They called it “a car with specialists”.

“Why are you like this? Tired? Want to sleep? He hasn’t even finished the chocolate bar,” I was handed the second half of the snickers. I finished it.

There were several papers, it was written that it was a “testimony”. I didn’t know what it was, and didn’t understand my status. I signed everything, including a statement to the effect that the testimony was “recorded correctly from my words”. I was at this place for the second time, and I tried to look around: it seems to me that the building was made of pale bricks, [there was] an internal parking lot, at least from one side – normal housing.

Search. Lists with passwords

I was taken for a search. The details of driving to my apartment block was only known to Bondarev K.A., and he explained how to park. There were cars everywhere. The FSB agents introduced themselves, showed their IDs to the porter and told her that they would be conducting investigation, and that they needed witnesses not from the inhabitants. She asked: “Which flat?”, but they replied that that was a secret. She called up some cleaners, and one of the agents double-checked: “Are they Russians?” “Yeah,” the porter replied.

They took the keys out of my rucksack and opened the door. Two agents rushed forward: “Get up! Get up quickly! Get up!” was heard from the room, then there was a sound of something falling down. Stepan [the neighbour in my rented flat] fell down. The agents rarely called him anything but “Bandera”, “Stepan Bandera”, and several times called him “crazy” or something like that.

There was a man with a bag, he took a printer and a laptop out of it, and placed himself in the kitchen. I don’t remember when he came. Then in the middle of the search, two more agents came, they were “busy” with Stepan in another room. They asked all passwords for Stepan’s multiple laptops, smartphones and so on, and attached them, written down on bits of paper, with tape to the devices. Immediately after entering, the agents called to ask other men to come to pick up Stepan.

“So he was telling you something? Well, it’s obvious, but you have to say that it happened. Well, that he made some off-cuff remarks in messages, it was there, understood?”

The balcony, room, hall, kitchen. They had to explain to the witnesses that they had to follow the agents and observe. It was clear that they wanted to make the search “clean”. I was surprised they didn’t plant anything on me – it seemed they prepared a secondary role for me. After all, it would have been stupid to plant something in my rucksack after I passed all controls at the airport. The witnesses didn’t move on their own, and looked at the floor most of the time. I tried to place my leg in such a way that the blood spots on my jeans were visible to those present, but I think it only made an effect on Stepan, and made him even more afraid.

“So, you will receive a copy of the protocol from us,” said the man with the printer, pointing at me. Some lists and seals had to be signed, attached to the bag with confiscated stuff. After signing the stickers with seals, the witnesses were dismissed. By the way, all devices were placed in my luggage bag, tapped with scotch and sealed.

We already were in the kitchen, where the man with laptop was writing the search protocol, when two more men entered. I barely saw them, only heard. They took “Bandera”to the room, and started “working” with him. “So he was telling you something? Well, it’s obvious, but you have to say that it happened. Well, that he made some off-cuff remarks in messages, it was there, understood?” Stepan clearly did not understand, and they were almost shouting in the room. Konstantin Bondarev rushed into the room to calm them down and close the door, because he was trying to build a “cooperative” relationship with me and understood the damage of trying to persuade my acquaintance to testify falsely against me. I heard everything, but didn’t show it. Bondarev K.A. didn’t comment on the behaviour of his colleagues, perhaps he thought that I didn’t understand anything.

I was sitting on a chair, it was still impossible to think. Trying to comprehend the information, I understood – they were going to put me away in any case, their “good attitude” was just a tactic, a distraction, to avoid using threats unnecessarily.

“Are we taking this one too?” asked an agent from “my team” after the colleagues who were taking Stepan away. “Yes, somehow he doesn’t agree,” was the answer.

At some moment, my clothes were “changed”, I don’t remember. First, they instructed me to take laces out of my shoes, then collect underwear and find a sweater, implying that it would be cold at the temporary detention centre. They ordered me to take off my trousers, somebody thrown Stepan’s sweatpants from the drier. “Change your t-shirt too!” was another order. I took off my old worn blue t-shirt for travelling with the word Kazakhstan on it and was looking for another one. I found an equally old t-shirt “Vintage Holiday”, which was a gift from my old friend Boris, also thrown thermal underwear pants in the bag and put a decathlon sweater above my thermal shirt. It’s better to sweat than to be cold, I thought.

Also in the hall they took everything out of my purse, put all my cash, around 2,000 roubles, into the rucksack. I put the same banknotes in the back pocket [of my trousers], which I still had on then.

The FSB building. “Testimony” and its editors

At the FSB building we were waiting for some permits at the entrance. Across from me a man was sitting, dressed in a MultiCam uniform, his face concealed; next to him – a guy in a red sweater and a lady. They had a lively discussion, but I didn’t understand anything, I was ready to fall asleep. At some point, a short man with his face covered, but without a hat, was standing in front of me. He was talking to the agents, but I could not understand anything. His hair was partly grey; he wore black and had cargo trousers, of dark, almost black colour. He was looking very much like one of those “specialists”.

At the checkpoint, at exit and entrance, the agents threw their IDs into a tray under a large window covered with a mirror, a minute later the IDs were returned in the same tray. We took a lift to the third or fifth floor, and then climbed up one more floor. I was brought to a room in the depth of the hall, there was a man in it.

Something more or less similar to the [previous] “testimony” was happening: clarifying questions and a request to sign the documents. Apart from two aspects: the first list, which was put on the table for me, said that I was a witness for such and such case. There was the surname “Pchelintsev”. I asked where my lawyer was. The man smirked and answered “A lawyer? You’re a witness, you are not supposed to have one. But do you have one? I can call. Give me a number?” I didn’t know any numbers of lawyers.

“Alright, take the chair and leave”– that was the second strange moment. We left, I was sitting in the middle of the hall, facing some door, which the investigator entered with a print-out of my “testimony”. I could hear them discussing my “testimony” from behind the door. When he understood that I could hear them, the investigator looked out of the door. Perhaps, it was a double door, later I couldn’t hear anything. We returned to the office, he gave me six sheets of paper that he’d taken way: “Here, read and check,” he told me with a smirk. I was reading – well, everything was like in the “testimony”, I was trying to pick up on the phrasing, and one sheet was even re-printed, with the word “constitutional” changed for “state”.

At this point, Bondarev K.A. arrived, brought me tea with sugar (two spoons, as I asked). Then I could not contest even separate terms – they told me that it depended on them in which detention centre I would end up, and I should better cooperate. I signed everything, including that I knew that there was Article 51 of the Russian Constitution [which protects against self-incrimination], which didn’t work – if I had used this right, the agents of FSB would have violated all my other rights.

The investigator took the papers with my ‘“witness testimony” out of the room several times. It became obvious that this story, authored by the FSB agents, had editors-in-chief, who were checking that nothing contradicted the general line.

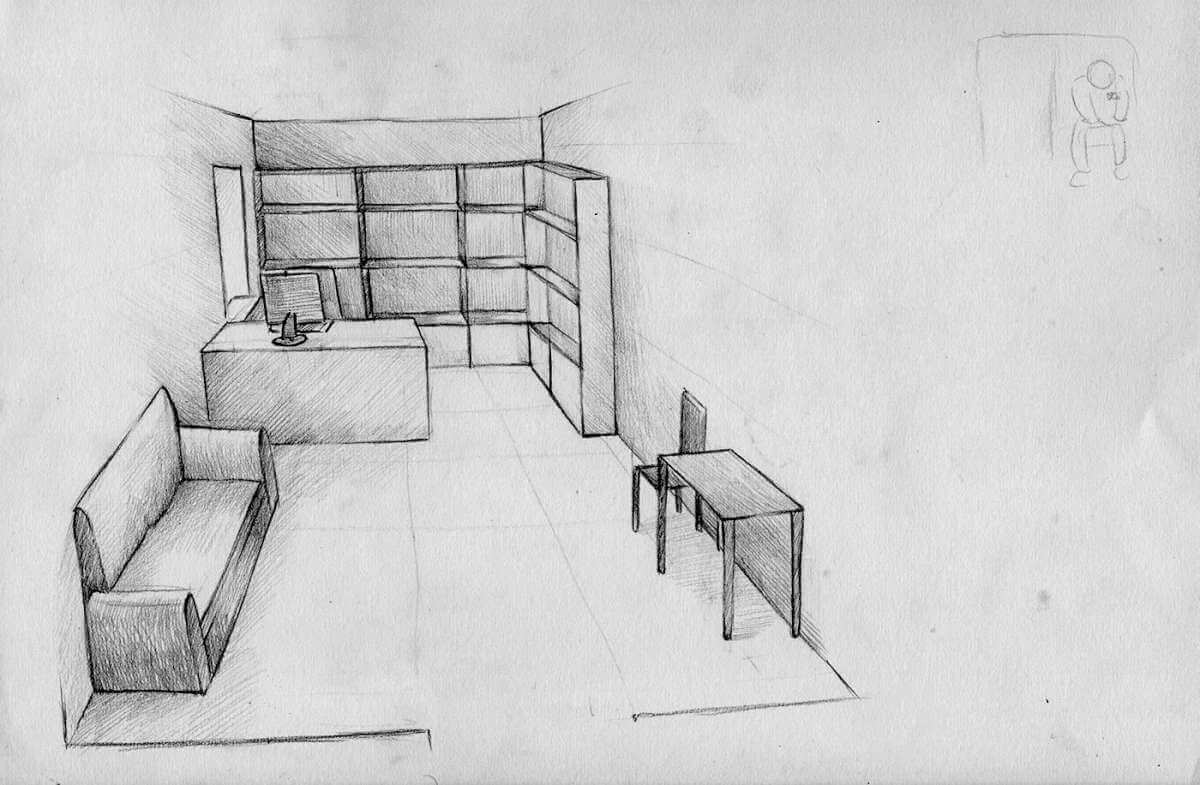

Most of the time at the FSB, I spent in a small room of investigator Alexey on the second floor in the beginning of the hall. It was much smaller than [the room] of the previous investigator and the investigator Belyaev G.A. There was a sofa there (on which Bondarev K.A. allowed me to nap for a short period of time in the middle of the day), a large table with a computer (used by everyone), some shelves, a window (everyone smoked through it), a chair (I was sitting on it) and a little table (in vain, I tried to nap on it). Investigator Alexey said that he had been recalled from his vacation, that officially he was away, and that he didn’t understand what was going on. He also allowed everyone, including Bondarev K.A., to use the computer in his office, only warning them that some people would come for identification and then everyone would have to leave.

FSB Building. Conversations with agents

What was happening the next few hours in the building of St Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast Directorate of FSB, I remember only partially, I could separate time into three general parts – before 7pm, from 7pm to app. 11pm and later. But I could not locate all events precisely in each time interval.

Before 7pm, there were many informal conversations between the FSB agents and between me and them. Arrests, [Vyacheslav] Maltsev, [Alexey] Navalny, protests and so on were discussed. One of the men who were in the office for a long time looked, in comparison to others, young – he was a bit chubby and lazy. I think, he was in the first pair that arrived at the airport and dealt with my smartphone. According to his own words, he was in “the car with the specialists”. “I was in that car, what were you shouting there about your wife? That you love her? Seriously? And why ‘krya-krya’?” “Because it’s a duck” I shrugged, as I understood that they were searching my Telegram account. My wife has a duck as her avatar, and her account there is called krya krya.

Also he was telling stories how earlier he had caught Nazis. For example, how he caught “Antitsygan”, who “was happy that he got 13 [years]” [this is likely a reference to Russian neo-Nazi Georgy Timofeyev, nickname Antitsygan – literally “Antigypsy” in English, from the gang NS/WP, sentenced in 2012). At some point he got a call, after which he went to “arm himself” – so it meant he had to act as a convoy somewhere. He returned in the evening, with a small gun (perhaps, Makarov) in a holster with a space for the second magazine, attached on the right to his belt. He was dressed practically – a black sweater, black cargo trousers. When he saw my wife’s cargo trousers from the Splavbrand during the search, he exclaimed: “He has trousers just like me!” But he didn’t have Splav trousers, even though, on the outside, they’re almost identical.

The relations between agents were friendly; [they were] somewhat dismissive towards subordinates, and evasive and compliant towards those of the higher ranks.

He was not very enthusiastic about working on my case: when Bondarev was asking him to finish the second version of “testimony”, complaining about the third day without sleep, he usually replied: “No, I am on the team, but I don’t quite understand what this is about.” He was trying to avoid work as much as he could – when other agents were called on the phone, he gesticulated that he “was not there”. Moreover, he managed to sleep, sitting on the sofa.

He also talked about how the TsPE (Center for Combatting Extremism, Center E) had nothing to do, so they were putting people in prison for pictures with swastikas. I immediately remembered how an acquaintance was threatened with a prison term by TsPE agents, who showed him a print-out of a picture of two [unclear] guys and a Nazi tattoo, which they found among his saved pictures.

During the first and the beginning of the second periods in the FSB building they waged a war on computer viruses. The main enemy force was a virus that was a .bat file (performing batch script cmd.exe) which not only wrote itself in autorun.ini, but also created an icon looking like the basket, clicking on which concealed all files in the directory, changing their attributes. “And where are my files?” was one of the most popular phrases of the evening. The anti-Antitsygan guy explained that one must not click on the “basket”, but some agents still did. Over several hours, anti-Antitsygan manually restored his colleagues’ files and cleaned their flash drives. The computers in the building were not connected to either a local network or the Internet. The transfer of documents was done with USB sticks. When they got a free anti-virus somewhere, they started to scan the computer of investigator Alexey, during which malware software was detected, including two VBS-scripts for bitcoin mining.

Apart from his participation in torture and work at the FSB, he gave off an impression of a smart and technically competent man.

“So did you find something on his devices?” someone asked.

“How to say, not so much so far,” the man with the smartphone (perhaps anti-Antitsygan) replied.

For identification, I was taken away and sat on a chair in the hall, where I also had to communicate with FSB agents passing by. I told them my story, many were sympathetic, but all were united on one point: I would go to prison anyway, so it’s better for me “to cooperate with the investigation”, independently of my involvement in anything. From the conversations and short discussions with them, one could see their one-sided perception of many things, the fact that they’re “brainwashed”, one could feel their instrumentality, [they were] like puppets. The relations between agents were friendly; [they were] somewhat dismissive towards subordinates, and evasive and compliant towards those of the higher ranks. The hierarchy was palpable, even without knowing their actual ranks.

I barely felt sleepy at that moment, I had a feeling as if I was in somebody else’s body, and everything that was going on was unreal.

Anti-Antitsygan told a story about a Nazi with a swastika on his chest, who had to remove the tattoo to “clean” himself, because he was getting harassed at a prison camp. Some time the agents spent discussing criminal tattoos. Anti-Antitsygan was trying to find a volume of prison tattoos with commentaries, then called a colleague, who sent him a version of the book. Anti-Antitsygan was looking there for a goat, a donkey and a pentagram. He read the funniest entries aloud.

“Have you seen his tattoo?”

“No, show me,” that was a dialogue between investigator Alexey and anti-Antitsygan with a request addressed to me. It was inconvenient to roll up my trouser-leg in the calf area. Anti-Antitsygan “saved” the situation. “Yes, look, I took a pic of it,” he showed a photo of my tattoo on the screen of his smartphone. Most likely, the photo was taken at the hospital during the medical examination.

“O-o-o, what’s that? A goat? You’ve got a ‘residence’ in the hut [prison cell] guaranteed!’ investigator Alexey commented.

“And who is going to ‘keep you warm’?” asked Bondarev K.A. from the room.

“I don’t know,” I replied.

“And what about your wife?”

“I hope she won’t come,” I forced myself to say, trying not to think about my wife being tortured.

“You what, haven’t understood yet?” Bondarev K.A. was surprised.

“XXX is still free, why?” he mentioned a woman’s name.

Somebody among the agents tried to change his mind: ‘“Let it go, he will later understand everything himself.” Then a whole list of female names (five-six) was mentioned, most of them I heard for the first time in my life.

“Where are they all? Haven’t understood yet? Free, because we are not animals.” I was indeed confused by what was going on. “We don’t take girls. Only guys will go to prison. Feminism is a good thing, but we don’t think so. There was no order to arrest the girls. But we will [hurt] your wife even in Kiev, if you misbehave,” he finished. I got scared.

The FSB building. “The General himself”

Even before the war on viruses, there was terrible news: the first version of my “testimony” was not accepted, it did not satisfy the bosses. Bondarev sat in front of investigator Alexey’s computer and started typing a new version. Until the very end, he was complaining that he hadn’t slept for a while, that he didn’t understand what he was writing himself, and begged his colleagues to change places with him and check what he wrote before it would be passed “higher up” for approval.

Typing indeed took a lot of time, it was easy to believe that Bondarev K.A, was tired: he was squinting all the time, massaged his fingers, got up to smoke, and his speed of typing was incredibly slow. The colleagues refused to help him, but he managed to persuade them to do one “useful” thing: to buy a shawerma [kebab] around 7pm.

I agreed to eat shawerma – it was my second food of the day – and asked for water again. When they got back, the agents noticed that they were tricked at the canteen called “Seven types of shawerma”: they were given only five shawerma instead of six. As for drinks, they brought water for me and several bottles of kvas “Stepan” (perhaps, Razin).

“Were you tortured? You were accidentally hit in the car! Understood?”

At some point they started saying that “we” were waiting for a lawyer. As it turned out later, we had been waiting for a state lawyer for me. Closer to his arrival, they explained that I should not try to do anything. They motivated me in the same old way: a choice of a detention centre with tuberculosis-infected inmates was in their hands. Also during the day they repeated the threats of a drive in “a car with the specialists”, if I didn’t comply. Realising that this meant several more days without sleeping in a car with criminals, who could do shifts, without giving me any breaks, I complied. They also threatened to leave me without water. “There won’t be any water there. How long can a human be without water?”

There was almost no conversation about torture in the FSB building. My attempts to say that torture is inhumane, that I signed those papers because I didn’t have any choice, as I didn’t want to be tortured again, were quickly stopped. “Were you tortured? You were accidentally hit in the car! Understood?” My attempts were stopped not only by Bondarev K.A. When I realised that they were all in this together, I became afraid of talking more about the violence during the night. I was totally broken.

Somebody came by: he was referred to as “the general himself”. A thin old man, his clothing looked like a military uniform, but, it seems, was just an ordinary formal suit. Inside, after the checkpoint, I only saw people in plain clothing. “The general”, as I remember, also asked why I was there for so long, nodding in my direction. They replied that they were waiting for a lawyer.

It was obvious, that the “general” indeed had a high rank and could also approve my testimony. “Why is XXX there, when the general himself came?” He was untalkative, I don’t remember his voice, as well as the purpose of his visit. He sat for some time in the corner between the wall and the sofa and then left.

I was asked a few more clarifying questions: they were the same questions to check that I learned the material, which Bondarev K.A. had asked.

“Well, let at least Genka look at what I’ve written here! I can’t think anymore! I think this is total nonsense!” Bondarev K.A. gave up, getting up from the computer and leaving the room. Some time later a man entered and sat in front of the computer. Almost immediately he began to type something. “How did you learn about YYY?” asked the man behind the computer. “From the Internet, I got it from Wikipedia” I answered sluggishly. “Are you trolling? Do you have a note somewhere that you have to troll agents?” I heard from the sofa (perhaps, it was anti-Antitsygan).

“How is it? Total nonsense, right? I haven’t slept for 72 hours,” I heard Bondarev K.A. shouting to “Genka” from the hall. The man at the computer answered something, continuing his concentrated typing.

I barely felt sleepy at that moment, I had a feeling as if I was in somebody else’s body, and everything that was going on was unreal.

I was asked a few more clarifying questions: they were the same questions to check that I learned the material, which Bondarev K.A. had asked. They usually touched upon the topics that I invented myself during torture, when they didn’t believe that I didn’t know somebody or something. It was difficult to sustain the coherence of these stories: I couldn’t remember what I’d answered, and couldn’t say about all evidence whether I’d made it up or the agents.

The second version of the “testimony” was printed out and they ordered me to sign it, I don’t know what is written there, in the end. There were surprisingly many papers. After that, “Genka” inserted a USB stick, did something and took it away. I was told several more times that everything was going to be fine, if I cooperate.

The term “hat” meaning something bad was popular among the agents: “Made a hat, this is a hat.”

When I was alone with investigator Alexey, he told me that one could believe the agents’ promises: “Because FSB officers always fulfil their promises! Always! Understood?” that was already the second “FSB officers always” phrase during this day. The phrase was on my mind, often added with “use torture”. I decided that even Nazis did not deserve torture. In general, breaking the law, while being proud of protecting it, is absurd.

The FSB building. Interrogation

How I got to the office of the investigator, I don’t remember. I was sitting in front of him at the table. “Belyaev Gennady A.” the investigator introduced himself. He was the man who recently finished my “testimony”. “Now we are going to formalise your arrest, then do a search, then you will have time to talk to a lawyer before interrogation,” he continued. A state lawyer, witnesses arrived, the investigator searched me, obviously, it had nothing with me. The lawyer noted that it was not necessary to do a search, to which Belyaev replied that he just got back from his vacation and he didn’t understand yet what was going on, and also told a story how after an arrest pot was found on a suspect at the temporary detention centre and the quality of his search was questioned.

When asked whether I agree with my arrest and acknowledge my guilt, I replied negatively.”‘No? Sure?” the investigator double-checked. I confirmed that I didn’t consider myself guilty, that I didn’t break any laws, and knew nothing about preparing and committing crimes. Officially, I was detained on 24 January at 11.30pm, 28 hours after the moment when they took my smartphone from me.

“Well, here, you can talk in the corner at the window,” Belyaev G.A. pointed to the spot for “a confidential meeting with a lawyer, unrestricted in time”. He closed the room and went into the hall. I had only one question for the state lawyer: “What to do?” “To be honest, I don’t quite understand what is going on with you here…” he replied.

I told him briefly what kind of article they were trying to impose, that the prison term is from five to ten years of strict regime prison, what kind of papers I already signed, and that I had done nothing. “Well, it’s clear what they want, but you will get a suspended prison term for the first time…” When I heard that, I understood that the state lawyer had no clue where he was and what was going on. I had to interrupt him: ‘“There is no suspended sentence for [Article] 205 (“Terrorist act”)!’ My zero confidence in the inhabitants of this building now encompassed the state lawyer too. I didn’t tell him about torture, because I lost any hope of being helped. The state lawyer was telling me that the investigation would sort everything out and it was necessary to cooperate with it.

“Are you done?” asked Belyaev G.A., opening the office door. We entered inside. The state lawyer asked in which detention centre I was going to be sent. “First, to the temporary detention, and tomorrow after the court. It’s either Pre-Trial Detention Centre No.3 [SIZO-3], Pre-Trial Detention Centre No.4 [SIZO-4], or Kresty-2,” replied Belyaev G.A., looking at me. “It depends on different factors, how full it is, we will see where.”

“So are we going to cooperate?” he asked me.

“We will,” I replied.

“Do you acknowledge your guilt?”

“I do,” I replied, deprived of any choice and hope.

“Well, then I will compose the interrogation on the basis of the testimony…”

There were questions again, he was saying some utter nonsense. The investigator was interested in the details of my “stories”. As during the writing-up of the “testimony”, there were no checks related to the topics I learned in the minivan. The state lawyer asked “to leave space for pre-court [proceedings]”, and not to ask many questions.

“Hmm, in fact, there is no suspended sentence for Article 205. This is the first such article in my practice,” said the state lawyer. He was sitting on the sofa and looking at a smartphone. He returned to the table, when the “interrogation” was finally written by the investigator and it had to be signed. I was browsing, signing, and giving the pages to the lawyer. After the end of the interrogation, investigator Belyaev G.A. said: “I will inform the Consulate [of Kazakhstan]”. Obviously, the Consulate was not informed, as it turned out later.

After the interrogation, I asked the lawyer to get in touch with my wife and tell her what happened and where I was. “Alright, but if the investigation learns about it, that can undermine ‘pre-court’ [proceedings], if it affects the investigation,” he said.

Temporary detention centre

I was led by foot to the temporary detention centre. During the examination, a doctor came, he was standing in two metres from me and didn’t approach me. He asked me about my chin, I told him I hit myself.

“What about the spots?” he continued.

I looked at the agents, they looked at me.

“I don’t know…” I replied.

“Are they painful?”

“No.”

Then there was another question, and at that moment, the agents took the paper from the hospital and gave it to the doctor.

“What’s that?” he asked.

“Well, he is healthy,” they explained, “[He] was examined on the 24th. Somebody smirked that 24 January 00.30 was recently (I assume it was early during the night of the 25th of January), while in fact a whole day passed.

In the cell, it was dark and [unclear]. My neighbour asked: ‘First time or second?” He introduced himself, but I don’t remember his name. Asked why he was there, he named the article: “One hundred…. and five’, I don’t remember for sure. “Stabbed. With a knife,” he explained. I laid down and closed my eyes.

“Get up!” I heard the news that it was morning. I closed my eyes again, and opened them because of the noise: my neighbour was taken away. The third time – I was led away. “Rubbish!” ordered a man in uniform. I didn’t leave any rubbish, and didn’t even have anything, so replied that I didn’t have any rubbish. “Sure? All rubbish, even the rubbish that’s not yours!” he ordered. I collected a couple of cigarette butts, somebody’s socks and put them in a bag. Had I slept at all? I didn’t understand.

Court. “This is not a brothel”. Pre-Trial Detention Centre

I was brought to court. Some faces were familiar, also I already knew everyone in my convoy. In the car both times (to and from the court), they were trying to discuss with me informally various unrelated themes. I was still depressed and barely spoke – the agents did the talking. We spent some time in front of the court hall, then I was put in the cage, and the court began.

“…During the interrogation… the suspicions of the investigation accepted… no moderating connections… has income… bribing witnesses… arrest,” the investigator was gibbering.

The judge asked whether I agreed with the investigation. I replied that I didn’t know what to say. “Do you leave it to the court’s discretion?” she asked. “Yes,” I answered. The lawyer repeated: “At the court’s discretion.”

The state lawyer came to me a few minutes later and said: “Okay, I am leaving,” and then left the court.

Leaving, the judge said that this was for 40 minutes. At some point I lay down on the bench in the cage. The investigator Belyaev G.A. came and said that this was not a brothel and one was not allowed to lie down here. Then he asked some questions about my wife’s acquaintance and whether I would be able to identify her.

The judge read out the decision, then went to a room and returned in plain clothing. “If you refer to [Bondarev K.A.’s] report, you have to deposit it at court!” The FSB agents replied that it “was never necessary to bring anything and it was always fine”. In the court’s decision, it was written that the court studied the materials of the case, and that there was among them the report of the senior officer of St. Petersburg and Leningrad Oblast Directorate of FSB Bondarev K.A., concerning the discovery of the traces of crime.

In Pre-Trial Detention Centre No.3 [SIZO-3], the agents told me to take off my shoes and dress before a doctor arrived. “Well, it looks like it’s only the face,” the detention staff told the doctor. I again said that I was hit accidently. There were several diagnosing questions, I mentioned that I had psoriasis. The agents left, and I was waiting for something. A doctor came and again asked some questions, mentioned that I can ask for his help with psoriasis. I did not tell him anything about torture, because the FSB agents were still next-door – moreover, they may have conspired with the detention centre [staff].

***

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)