Ana Vračar, Zoran Veselinović: Could you explain the relationship between Unite and the Labour Party, and especially the way this relationship has changed over the last few decades?

David Condliffe: In recent years we had the Blair government, which was very difficult for us. This government didn’t want to talk about collective values, they didn’t want to talk about anti-union legislation, they didn’t really want to talk with us. When Brown came to power, things continued along the same lines. It was a very disappointing time for us, these 13 years of Labour. We learned a lot from this situation and many unions had numerous calls to disaffiliate from the Labour Party at the time, especially because of the privatisation attempts on the Royal Mail. But many decided to stay, as did Unite. After the coalition was put in, we were exposed to more attacks. Then we got Ed Miliband elected, and there were good signs that he was listening and that he was more in tune with our values and our aims, but he couldn’t take the party with him. We campaigned during the elections, we did what all unions do, we supported the Labour Party through lots of money. We funded the Labour Party through the elections, we let them use our premises, supplied all the materials, I think we spent £4 million trying to get the Labour Party elected, but the narrative was difficult to sell, and there wasn’t much difference between the Labour Party and the Conservative Party. So, although we campaigned physically, mentally we didn’t really campaign.

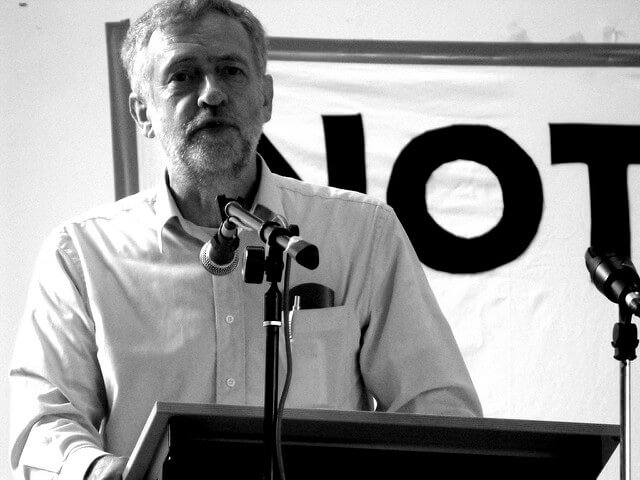

What changed when Jeremy Corbyn decided to run for leader of the Labour Party?

David CONDLIFFE

is Unite the Union’s East Midlands Community Coordinator and Unite in Schools Coordinator.At that point we had lost the election, but it turned out that something good was to come out of it. First of all, we concentrated on getting more of our members involved with the Labour Party at the grassroots level, because at this point our membership had switched off and didn’t want to get involved. It wasn’t seen as a good thing for our members to become Labour Party members, but that all changed in the last year or so. Then, when the candidates came forward – Andy Burnham, Liz Kendall and Yvette Cooper – we saw that there really was no one we could get completely behind, so we took one month to think about who we’re going to back. This was all over the news because we were seen as the kingmaker, having had Miliband elected and all. For a while, we got a lot of questions about why we should support anyone at all, since we had already spent so much money and none of them actually speaks to our membership. But then came the first Corbyn meeting in Nottingham, in East Midlands where I work – a few hundred people appeared, and that changed something. In the end, we went for Corbyn first, Burnham second, and then it just went mad.

Could you describe Corbyn’s campaign for leader of the Labour Party and the role of Unite in this campaign?

Well, we never saw anything like the first Corbyn meetings. We knew Corbyn for years, we could call him on a meeting and, ten years ago, maybe a few people would come. But something happened with young people in the meantime, with how they react to his honesty and his integrity. Half of the people attending the meetings were under 30. We couldn’t put that kind of youth in the room, the unions couldn’t do that. There was something in the way he spoke and in the fact that he didn’t really seek out that role. Of course, it was a real struggle to get 35 MPs to back him, but once we got into the campaign it was just remarkable because I think no one expected that kind of exposure, that kind of fire. Even in some moderate cities – don’t forget that we had just lost the elections and a lot of cities had gone blue – when we arranged a Corbyn meeting with one day’s notice, a thousand people came. And then when the elections came, he won on all three platforms.

How is the leader of the Labour Party elected, and what is the role of the unions in this process?

Now the Labour Party has become a more grassroots led organization and that’s exactly the membership that will keep the attacks off the unions.

Ed Miliband changed the system. Before that, the unions could vote on block and now they vote individually. In the recent election, you had Labour Party members, affiliate members and associate members voting for the new leader, so people could pay £2 to join the party and have a vote. After that, we sought to make them full members of the Labour Party. We’re not the Labour Party, we’re an independent trade union. We’re two different formations and we respect that, and we expect the Labour Party to respect that too. At the same time, we see the Party as a vehicle and if they open up the door for people to join for £2, we consider that a good strategy. It’s not unlike community membership in Unite. I don’t know how they came up with that, but it worked, and membership is now at 420 thousand as opposed to 200 thousand. So, now the Labour Party has become a more grassroots led organization and that’s exactly the membership that will keep the attacks off the unions.

Can you tell us something about the collaboration between Corbyn and Unite today?

Corbyn is working well with all unions. He believes in unionism and he wears our badges. He wore an I LOVE UNIONS badge to the TUC’s [Trades Union Congress] recent day of action against the Trade Union Bill. That was unheard of, you would never get Tony Blair wearing a union badge, would you? He speaks our language and he sticks to his principles. He’s a man of Stop the War Coalition, so we have a connection with him there too and he’s already committed to us on the Trade Union Bill. Should he be elected, they’ll repeal it. He’s also been very supportive in the recent dispute that has been going on with the junior doctors, he goes to their picket lines, he supports re-nationalisation…

How come Unite decided to stay affiliated to the Labour Party in spite of the disputes that were going on after the Blair era?

Well, basically unions face two decisions regarding the Labour Party. Either you’re staying and trying to drive it in the way we want it to be driven, or you pull away. There was a lot of talk about disaffiliation and some organisations, like the RMT [National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers], disaffiliated a long time ago. People started asking questions, wondering why we were funding the Party and not getting anything from it. It wasn’t as bad with Unite as it was with smaller trade unions because we had a strategy. We knew it was going to be a 5, 6, 7, 8-year plan to get people in at the grassroots level and to get MPs with our values to get elected. We now have 36 MPs elected. And of course, once we got Corbyn in place, all talks of disaffiliation just went away. In the recent months, some of the unions came back to the Labour Party and I believe the RMT are also thinking about it. So, to come back to your question, it was a little bit of luck with Corbyn and the voices about disaffiliation died down.

How do you engage members to participate in the Labour Party at the grassroots level?

[easy-tweet tweet=”Corbyn is working well with all unions. He believes in unionism and he wears our badges. “]

We do different things, but one of them is the Candidate’s programme, where we recognize people who are connected to the local community and who are Labour Party members, and we ask them what their aim is. Do they want to become councillors? Do they want to become MPs eventually? If people show spirit and we think they can make a MP who will keep to their principles, we’ll support this person for 5-6 years and when the election comes, they’ll be able to stand in their constituency. So, not only will people become members, they’ll actually get involved with the Labour Party and that will help us get the Party on our path. We also have a political school every year. It’s a big thing, we get up to 150,000 people and we hold a school that culminates in this big rally in the small town of Durham, and we bring all of our representatives to get empowered and inspired. Finally, we have one person in each region as a political officer, whose job is to liaise with the Labour Party, with the TULO [Trade Union and Labour Party Liaison Organisation], to build counselling networks, etc. So, we have the grassroots level, we have the regional level and we’ve got the national level all covered.

Our next topic is the Trade Union Bill. Can you explain how it came to the drafting of this Bill?

Well, why do you think the Trade Union Bill is happening? It’s not happening because strikes are out of hand in the UK, it’s not because we’re undemocratic, it’s happening because it’s a decision made by the Conservative Party. They’re doing it because the last big privatisation attempts in the UK, that of the NHS [National Health Service], of the public services, they can only be stopped by organised labour. So, if they destroy organised labour, then their privatisation plans go through – they’re moving barriers to their neoliberal agenda, that’s what it’s about. So, this Bill is really about destroying organised labour and making it easier for them to privatise, to have a low-paid service economy which is not organised.

What are the key elements of this Bill?

They put some really amazing stuff about our use of social media, where we would have to give an employer two weeks’ notice before we did a tweet about the dispute. If we wanted to set up a Facebook page, we would have to give the employer a notice two weeks before. Things like those were put in the Bill so they could take them out later and say that they have listened to us and taken some of the things out. But the big problems are the thresholds. What they want to do is, if there is a threshold of 50%, they want to have a 40-50% yes vote inside this threshold. Some unions like the RMT won’t have a problem with that, because when they ballot they get a 80% turnout and a 75% yes vote. On the other hand, with some of the big organisations, like the NHS and the councils, we might get a smaller turnout, 10-20% turnout. And they want to make that kind of turnouts illegal. So we’ve said, okay, if you want the thresholds to rise to 50% turnout and 45% yes vote, allow us to do electronic balloting and workplace balloting. We’ve said that if it was about modernizing, we’ll be happy to modernize, especially taking into consideration that everyone else is using this kind of balloting, including the Conservative Party.

Could you explain some other elements of the Bill?

This Bill is really about destroying organised labour and making it easier for them to privatise, to have a low-paid service economy which is not organised.

Another important element would be the length of time that a strike ballot is legitimate for. What they said in the Bill is that it would only be valid for three months, so you would be time-constrained in your negotiations. They also want to increase the period we have to give the company when we want to ballot. Don’t forget that in the period when we decide to ballot members, they can deploy tactics to break the unions. So if we give them a month’s notice, that’s four weeks they can use for lobbying, and when we get to the strike, people won’t be so sure they want to strike anymore.

Does the Trade Union Bill change the possibilities for unions to organize strikes or negotiate with the employer?

Yes. Now, if there’s a strike, you can’t use agency workers to break that strike. But in the Bill they are going to allow that. Can you imagine that, sending agency workers to cross a picket line and carry out work of the striking workers? But my real worry with this is they won’t use agency workers, they’ll use unemployed workers through workfare. They’re going to put really vulnerable people into the position of crossing a picket line and doing a day’s work.

Can you explain the term workfare?

If you’re unemployed in the UK, you get £75 a week of welfare and in the case work becomes available, you have to take it. So companies are now using free labour by using this policy. We have a lot of our members on workfare now and they say, “I know it’s £2 an hour, I know I’m getting exploited, but if I work hard for these six months, I might get a job.” It’s heartbreaking because they finish those six months and the company gets somebody else, because it’s used to get free labour. So it’s an insidious policy and every time we find that a company is using workfare we campaign against it, but it’s hard. Once companies get used to free labour, how can we negotiate for pay rises or pensions?

Besides the Trade Union Bill, zero-hour contracts are one of the big issues in the UK. So, could you describe the issue of zero-hour contracts?

Zero-hour contracts started off, as I understand it, in the education sector up to 10-15 years ago for visiting lecturers who would just come in and they wouldn’t need a contract of employment, their contract would be zero-hours. At that time it was seen as a flexible approach to meet that need and it didn’t seem to be exploitative. It just seemed to be a contract that fitted the need of that group of workers at that time, and there wasn’t too much worry or too much outrage about it. As time went on, mostly in the retail sector people thought this is a great idea, employers thought why would we give people a contract of employment that then gives them rights to pensions, gives them right for us to pay sick time and gives them right to holidays. Why would we do that when we can just give them this zero-hours contract, so that we don’t have to guarantee them anything?

So the retail sector really took hold of zero-hour contracts. And it was sold in the British press as being a flexible approach and that students loved it.

Once they’ve been in place for a few years, we started to get some facts about zero-hour contracts. The average age of people on them was up to 35. The amount of time people were on zero-hour contracts was between 6, 7, 8 years. You couldn’t get a mortgage on a zero-hour contract. You couldn’t get a loan on a zero-hour contract because you could not guarantee how much money you would be earning. Some weeks you would have zero hours, other weeks you may have 40 hours.

The only people winning on zero-hour contracts were the employers. There was no money coming back into the system.

And then a big thing came out through Vince Cable when he was in the Coalition government. The government wasn’t claiming national insurance contributions from these contracts. So it wasn’t even benefiting the state. The state wasn’t getting insurance contributions to help pay for the sick pay that many of these workers may need to claim. The only people winning on zero-hour contracts were the employers. There was no money coming back into the system.

It was estimated that there is 800,000 people on zero-hour contracts. We estimate that there must be close to 1.5 million on zero-hour contracts. So what we’ve done recently is we’ve targeted one of the real big users of zero-hour contracts, a billion pound company Sports Direct, to say, “look, it’s not small shops or students that use zero-hour contracts, it’s big companies.”

Sports Direct is a company that is now infamous for its ‘Victorian’ working practices and an extremely high number of workers on zero-hour contracts. Can you describe the ‘Sports Direct model’ and Unite’s campaign against this model?

Sports Direct employs 28,000 people in the UK in 440 stores. In their stores 21,000 are on zero-hour contracts. In a place called Shirebrook, which is in Derbyshire, they have this big warehouse that employs anywhere between 3,000 and 5,000 predominantly agency workers with, I think, 300 permanent staff, and the rest 4700 employed by the agency.

So, we started last September and the campaign was twofold: to ban zero-hour contracts in the stores and to move all the workers at the warehouse from the agency onto permanent contracts and to a living wage, and basically to expose the working practices that were going on at Sports Direct.

We worked initially with Channel 4 to do a programme called The Secrets of Sports Direct where they put undercover people in there and they filmed what was going on in there. That was the starting point before the big launch in September. We’ve known what’s been going on there. We’ve been saying for years what’s been going on in Sports Direct, and no one’s been listening. So we had this campaign to really, but creatively, expose Sports Direct, and to use community and young members at the forefront of driving this campaign. So the first thing we had to do was to tell the public what was going on there.

We had this thing about zero-hour contracts and agency workers, but people were saying, “that’s not bad, that’s just normal now in the UK.” So we had to move on to what was actually going on in this warehouse. We had the initial story of when a young Polish woman gave birth to a baby daughter in the changing room of Sports Direct, which was horrendous. She asked two or three times to be able to leave and go to the hospital. She was told by one of the managers there that if she left, she wouldn’t get any work the following week. Once this started to come out, this level of fear amongst workers getting hours for the following week and that young woman felt so fearful that she’d given birth to a baby daughter, everyone was saying, “wow, what is going on at this workplace.”

Then we put Freedom of Information Acts in through the BBC. They found out that there’ve been 78 ambulance call-outs in one year alone to one workplace due to low level accidents and a worker having a seizure in the canteen at dinner time. People just thought he was asleep.

[easy-tweet tweet=”Once companies get used to free labour, how can we negotiate for pay rises or pensions?”]

Once these things started to come out we worked with the Guardian to get them to put undercover reporters in there. Then they exposed the searches that were going on. We were saying that people were being searched for two years. We said that men and women queue up to be searched when they finish their shifts. They do their eight hours, they do their ten hours, they swipe off, they finish, and then there is this security section where they queue up to be searched. They have to show their underwear to show they’ve not stolen anything from Sports Direct.

So, once we started to expose that, that’s when the campaign really took hold. We infiltrated their AGM, we bought shares and we asked questions to Mike Ashley, the owner, about what was going on there. He denied that searches were taking place, in front of all the press. When we spoke to the 2,000 workers that came out of shift change, they were saying to us, “no searches today”. The day after, searches were put back in place. Now, he was starting to become this person that’s just a spin doctor. The press saw that and reported that the searches were going on the next day.

We started to expose more and more, through working with the Guardian and the BBC, about the way the housing in Shirebrook was linked to the people who worked at Sports Direct, how housing was being changed instead of three bedrooms into seven bedrooms and how landlords were making money by exploiting people through housing. Then we heard a lot of cases about sexual exploitation for hours, to get work the following week.

As workers got more confident, all the stories started to come out and people started to join. But what we are up against is when we go to Shirebrook and give a worker a joining form, and there are cameras and they see that worker, we know that they say “you joined that union and that’s it”. So we have to be really sort of clever how we organize.

As for the public – as with any public, as with human nature – if they see an injustice, if they see something that’s this unfair, they want to do something about it. So we’ve attacked their [Sports Direct’s] share price and their share price is halved, their valuation is gone from 4.8 billion to 2.2 billion. It was a normal organizing tactic on company reputation and their reputation is going downhill now.

The final thing is, after six months of campaigning, he’s [Mike Ashley] now been told by Parliament that he has to go to Parliament to answer questions about his employment practices at Sports Direct, which is unheard of. And what’s even better for us, he said “no”.

That puts in question the power of Parliament.

That’s a great position for us because we have this sort of argument going on between the politicians and a big employer, and the public will be watching. There’s a lot at stake on June 7. Don’t forget, they’ve interviewed Murdoch on the press inquiry, they’ve interviewed Google…

Don’t forget, there’s a class issue. Mike Ashley is not old money, he’s new money and he’s resented by a lot of the Tory MPs who come from old aristocracy, old money, and they think this working-class man, who’s got new money, doesn’t want to answer our questions.

Big stakes, and that’s come about from the start of the campaign.

Could you briefly describe the conditions in which migrant workers work at Sports Direct? On what kind of contract are they usually employed? Is that different from British workers? Do employment agencies play a role in the workers’ coming to Sports Direct?

We estimate that there is probably 700 British workers working at Sports Direct [the warehouse in Shirebrook] and probably between 3,000 and 4,000 migrant workers working there. Initially, Sports Direct was employing directly from Poland. They would advertise their jobs, ‘these fabulous jobs’ in Sports Direct, for years in Poland.

There is only 300 permanent jobs, permanent contracts at Sports Direct, and that’s a mix between British workers and migrant workers, and that’s along the lines of being team leaders or being in managerial positions. Those people stay in those positions because Sports Direct pays a bonus system of every two years up to £30,000. That’s what drives people to manage people in the way they manage because they’re driven to get this bonus, £30,000, which is linked to share price. So what Mike Ashley has now said about us, “you’ve affected the workers, you’ve driven the share price down, so we can’t pay as big a bonus to our managerial staff.” Money for that section of the workforce that’s on permanent contracts and as team leaders is a real driving factor. That’s not based on nationality. It’s done purely depending on whether you are in a managerial role, whether you want to manage people in a certain way.

If you work at Sports Direct and it’s a picking job in a warehouse, you would have targets for a number of orders you have to get per hour and these are constantly changing, so you can never reach them. They have a Tannoy system that names people. If they’re not working fast enough, they name “such-and-such you’re not working fast enough, you’re now behind on your order sheet and go faster”, hence the 78 ambulance call-outs because people have been driven to work so hard to meet their targets. So the team leaders are driving that because they want this bonus at the end of the two years.

They are using people who can’t speak the language, who don’t know what is actually going on, to exploit them.

The big problem we have is that they [non-managerial staff] are employed by agencies, which we don’t have recognition with. Agencies take certain admin fees of them. So they take up to between £7 and £8 a week for this admin fee. We are trying to find out whether that’s legal or not. I think the workers can claim it back if they travel 20 miles to the city where the agency is based. So if you got £8 to 4,000 workers every week, it’s quite a nice pot of money for doing nothing.

As I’ve said before, predominantly they would advertise in Poland, but I think Polish workers are seeing now what’s Sports Direct like and they are saying, “no, it’s not great”. So they’ve moved advertising to Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, around Eastern Europe.

It’s a big company. It doesn’t need to employ people through agencies. It can employ people on permanent contracts. Yeah, working hard, but on permanent contracts getting paid a living wage. Whether you are from Poland, Slovenia, England, Scotland, it doesn’t really matter, you shouldn’t be exploited. They are using people who can’t speak the language, who don’t know what is actually going on, to exploit them. That’s were our English language classes come in and they can understand what’s happening to them more and then they can make an informed decision whether they think they are being exploited or not, whether they think they should join a union to stop it.

You mentioned language courses, are there any other activities that you do with migrant workers?

We want to socialize. We do a lot of socializing together, a lot of relationship building because a big problem in Shirebrook is that the British population there and the migrant population have not been getting on. There’s been a couple of stabbings. The media want that to happen because they don’t want them to come together. They want the British and the Polish, Slovenian, Slovakian workers to be arguing with each other about cultural differences and that way they are not focusing on Sports Direct… We’ve seen the rise of the Right and they are saying it should be British jobs for British workers, but 700 British people work there equally exploited as any other worker there.

The media want the British and the Polish, Slovenian, Slovakian workers to be arguing with each other about cultural differences

We are bringing out with us together cultural events where everybody brings in food from their homeland. We are really just building relationships and talking to each other. Today, we have a celebration event – I should’ve been there today, but I’m here – for the 150 people that are just under the three month ESOL course and we are going to give certificates, all are bringing food in and we booked a disco – disco, I know that’s an old fashioned word. So we’ll have up to 200 people in this former workingmen’s club which used to be connected to the mine – that’s the only legacy we have left from the mine – it’s going to be great to get all these workers together there, and just talking normally.

This process of organizing this way can be slow, but, if you organize this way, it builds deep relationships and it’s really difficult to break down once we organize this way. Slow, but really substantial if we can make it work.

Do you organize migrants into the union and how is that different from organizing workers from the area?

It’s obviously language problems sometimes; culture, language and explaining what a union is. Sometimes it’s no different than with young workers who just don’t know what a union is. “Why would they join a union, why would they need to be joining a union, surely all employers would treat them fairly”- it’s just getting rid of that naivety about what the world of work is about.

[easy-tweet tweet=”We’re all the same. It doesn’t matter where you’re from, you’re a worker. “]

We got a lot of ESOL classes that we set up through our community centres where refugees come in and we sponsor them into the union, we pay for their union membership. They come to the ESOL classes and they get integrated that way. So we are doing a lot of work around refugees and migrant workers, around language, that seems to be the initial driver to organize people, but [also] just to talk to them about what’s like to work in Britain, what rights they have.

We are obviously just trying to educate them what rights they have and obviously to organize with British workers. We’re all the same. It doesn’t matter where you’re from, you’re a worker. It doesn’t matter which country you come from, just come together as a collective. The big thing for us is this collective ethos. It has to be a collective ethos to come together to change things.

It’s just about building those relationships, so we’re stronger in the workplaces when we want to organize. I think all unions try to do that, it’s not just Unite.

There’s no education funding for free ESOL. If you came to work in the UK, the state would pay for English language classes, but, along with the austerity cuts, they cut all that. Unite is now one of the few organizations in the UK that can offer free ESOL classes. So I think it’s a great tool we can still help people with.

What is Unite’s position on Brexit and what are the reasons for that position?

The EU referendum is on June 23. The Conservative Party got backed in a corner before the last election by this ongoing campaign by UKIP to say we need a vote on our membership in the European Union. The Conservative Party has got a lot of Eurosceptics amongst it, so Cameron had to satisfy this big part of his party and he said, “if we get elected, we’ll have this EU referendum.” They got elected on a small majority which was a shock to all of us, and now he has to have this EU referendum which he doesn’t want to have.

The real interesting factor is that the Right is split on the EU referendum and the Left is split on the EU referendum. So, the Right is split on two sides. You’ve got Cameron and the government that wants to stay in Europe because they have this vision of a business Europe, of an employer led Europe on a big kind of TTIP level agreement, so it’s driven from the employers, it’s driven around business and it’s driven around this exploitation of the free movement of labour. That’s their vision of Europe.

The same side of the Right, which is Boris Johnson, from this old sort of elitist point of view on sovereignty are saying, “we are a powerful country, we need to make our own laws, too many laws are getting made in Brussels and it’s affecting our sovereignty, and we should come out just on that principle.”

We want a workers’ Europe. We want the social charge of Europe. We want the Europe that was envisaged when the EU was set up.

On the Left, the Left is split. You’ve got Unite and our position is to stay in Europe because we believe we can get better workplace rights. A lot of workers’ legislation comes from Europe which benefits workers in Britain. We have this vision where we want a workers’ Europe. We want the social charge of Europe. We want the Europe that was envisaged when the EU was set up. That’s our aim and that comes from the fact that we’ve got a leadership and membership which has driven Unite in a more progressive direction, especially around organizing the unemployed and organizing for social change and not just for workplace terms and conditions. So, the members have seen we’ve been able to do that with a big organization. Secondly, the Labour Party is now, for the first time in a long time, heading in a direction that’s true to the aims and values of Unite members. So we stayed in it, we changed it and it’s going in the direction we wanted it to go in. You have these wins, big and small wins, and they give you confidence, you go, “this is a good strategy, we should stay in Europe, we should change it and we should make it how Europeans wanted it to be.” So we’re going to vote for in.

On the counter to that, you’ve got organizations like the RMT which think Europe is an employers’ charter and it’s just going to get worse. It didn’t meet the aims that it was set out to do and it will never meet the aims that it was set out to do, so we should come out.

It’s going to be a really interesting debate, and it’s going to be really interesting campaigns on both sides. I don’t think anybody knows what the British public are going to vote.

***

Published in cooperation with Radnickaprava.org and OWID (Organization for Workers’ Initiative and Democratization)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)