It is well known that public monuments are seen as representations of power, whether contemporary or from previous periods in history. Statues, busts, fountains, public squares and a wide array of plaques and horsemen, among others, are materialized places of memory and clearly comprise a symbolic battleground. They often change in accordance with major political or societal shifts, as can be seen in many post-communist countries where communist symbols have either been destroyed or have become exoticized relics of a “distant” and “unrelateable past” – as is the case with Memento Park in Budapest or the Monument to the Soviet Army in Sofia. Nevertheless, the core symbolic significance of public monuments remains, whether it’s ancient Rome or contemporary Sarajevo. How do Belgrade’s statues fit into this context?

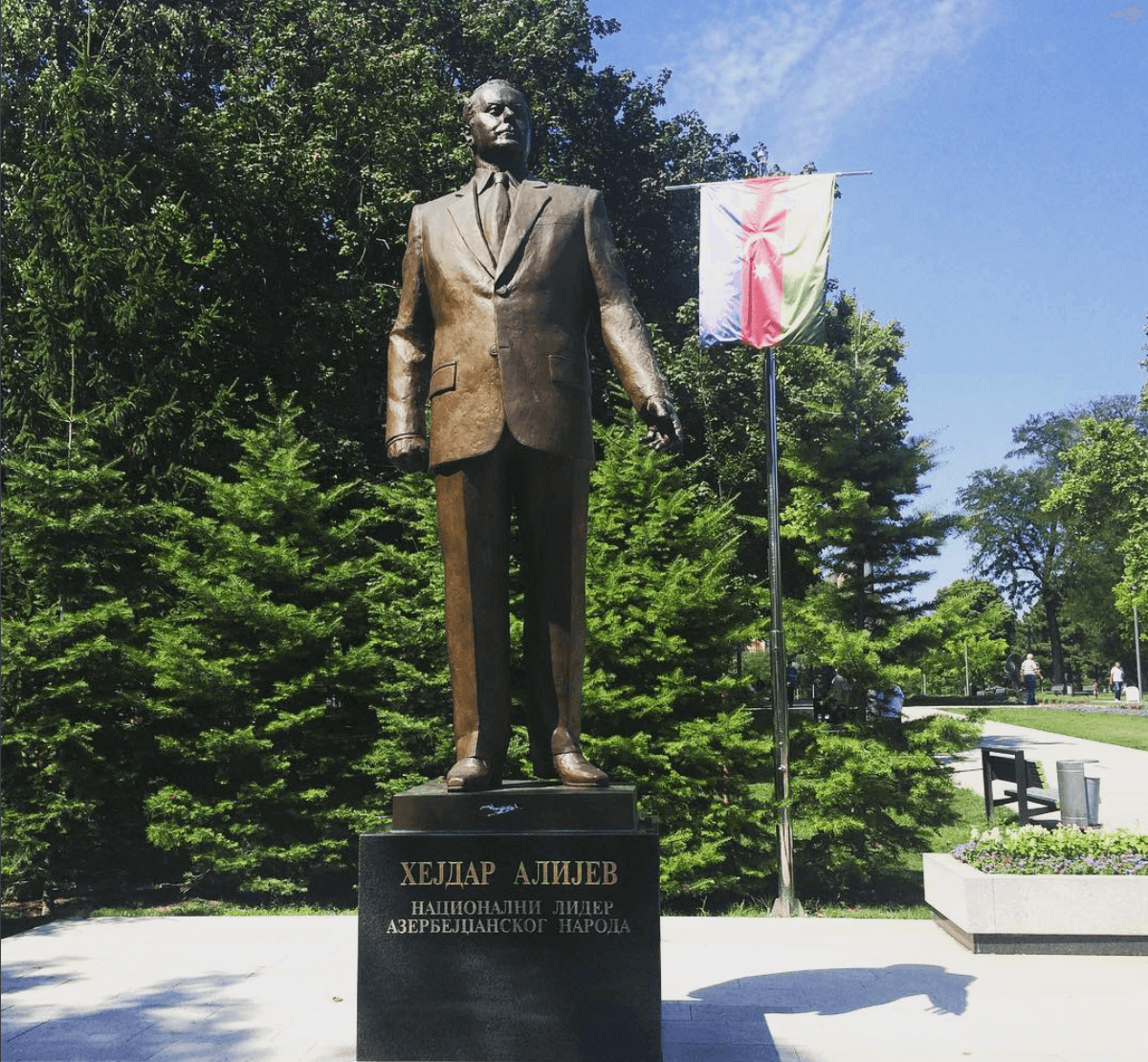

Although the process was initiated in the 1990s, one of the more recent examples of statue-making as as a symbolic indicator of power – or the shifting of power – was the government of Azerbaijan’s offer in 2011 to fund the redevelopment of Belgrade’s popular Tašmajdan park in the center of the city. As a prerequisite for the investment, a statue of the controversial former president of Azerbaijan, Heydar Aliyev, was erected. Aliyev’s son Ilham presented this “gift” to Belgrade, and participated in the inaugural ceremony for the new investment project together with former president of Serbia Boris Tadić and then-mayor Dragan Đilas.

This “tit-for-tat” approach meant to foster bilateral relations with Azerbaijan is not new: in 2012 a similar statue appeared in Mexico City and was also connected to the redevelopment of a park. The “Mexico-Azerbaijan Friendship Park” was, however, removed within a year after protests. Official Baku threatened to pull out of their investments in the country and even considered severing diplomatic ties.

Similar questions about the statue were raised in Belgrade, and most people were puzzled as to why a statue of Aliyev was chosen to represent Azerbaijan.

“Azerbaijan has magnificent poets, fantastic musicians, great singers and if any of them had been erected a monument in Tašmajdan park, it would have been a wonderful gesture. However, passing by Heydar Aliyev’s bust or monument every day is not quite a thing that people from Belgrade or any others should take pleasure in, especially if they care about freedom, justice and democracy,” Branka Šesto, former UN associate and leader of the Commissariat for Human Rights in Azerbaijan, told RFE/FL.

Vida Knežević from Kontekst Collective said that there were no good arguments for the presence of Aliyev’s statue in Belgrade apart from the fact that the renovation of the park had been financed by the government of Azerbaijan. Aliyev is not the only Azerbaijani whose concrete manifestation is present in Serbia – another monument dedicated to composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov, who wrote Azerbaijan’s national anthem, was raised in Novi Sad in 2011.

Aliyev was erected in Tašmajdan Park alongside a statue of the late Serbian writer Milorad Pavić. The author is probably best known to international audiences for his novel Dictionary of the Khazars, which was mentioned during the unveiling of the statue. Speakers at the event attempted to draw a connection between the two statues, by describing the Khazars of Pavić’s novel as modern-day Azerbaijanis.

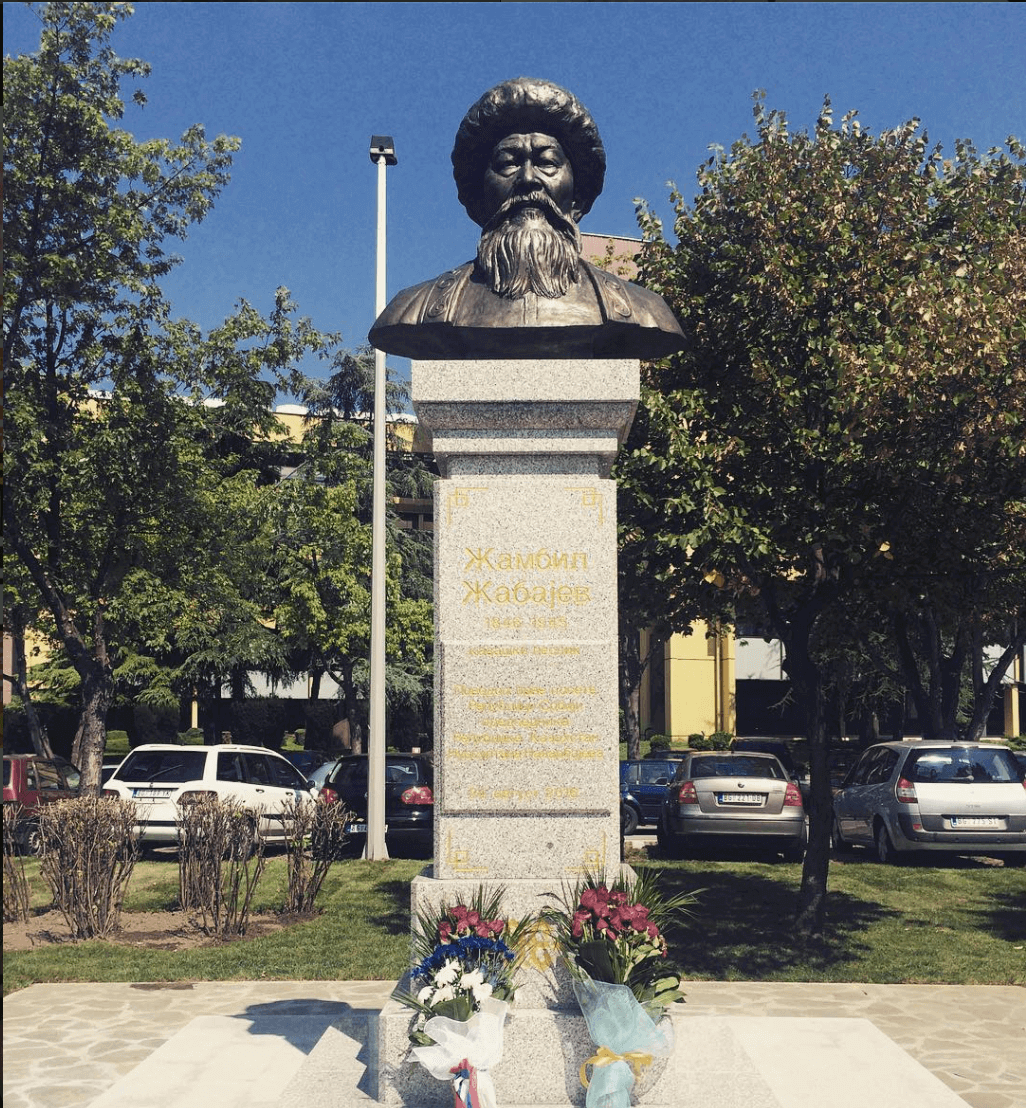

In 2016, a bust of early 20th century Stalinist poet and folk singer Jambyl Jabayev of Kazakhstan was erected in New Belgrade. The bronze likeness of Jabayev was installed during the first visit of Kazakh president Nursultan Nazarbayev to Serbia. Nazarbayev has served as the leader of Kazakhstan since 1989, and some say his style of dictatorship is redolent of that of Aliyev.

Monuments as a Form of Historical Revisionism

The changing of monuments and street names also reflects the shifting relations between Russia and Serbia. After WWII, Red Army generals and Stalin were predominant in SFR Yugoslavia; statues of Stalin didn’t survive Yugoslavia’s break with the Warsaw Pact in 1948, but monuments to others lasted until the nationalist frenzy of the 1990s.

The monument that perhaps best exemplifies Serbia’s confused approach to its WWII history is the monument dedicated to the last Russian tsar, Nikolai Romanov II. The statue was erected in 2014 by Russian president Vladimir Putin, who unveiled the statue himself. The Serbian and Russian patriarchs were also in attendance, which gave the entire event an overtly religious tone.

What is bizarre is that the statue was unveiled on the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Belgrade from the occupation of fascist Germany, the main reason for Putin’s visit. The Red Army assisted the Yugoslav Partisans in the liberation of the capital city – so it is ironic that the statue of the monarch who was executed by the Red Army, or the Bolsheviks, was erected on this day. The anniversary itself is not a national holiday in Serbia, but was celebrated in 2014 specifically to honor Putin’s visit to Belgrade.

The figure of Romanov II and its corresponding religious unveiling ceremony conveniently skips over the communist past, harkening back to WWI, when Russia was Serbia’s key ally (many Serbian churches even display frescoes of the Romanovs as Christian martyrs). By choosing an old ideological power figure, the gift appealed to both sides. The monument was strategically erected at Devojački park, next to City Hall, the Old Court (Stari Dvor), close to the Russian Cultural Center (Ruski Dom), thus marking the place where the embassy of Tsarist Russia was once located. It was made by Russian artists, as the inscription on its base states, as a present from the Russian Military-Historical Society, supported by the City of Belgrade and a fund from Moscow. The statue was flown in from Russia for the event.

Monuments Between East and West

Serbia’s so-called “balancing act” between the EU and the US on the one hand and Russia on the other has characterized the country’s politics for a long time, and is arguably reflected in some of Belgrade’s other ideologically (and otherwise) incoherent monuments. Recently, a statue of Borislav Pekić, a famous writer and a founding member of the pro-west Democratic Party (DS), was erected at the newly redeveloped Cvetni Trg. The initiative was set in motion by Pekić’s wife and supported by the Belgrade Rotary Club.

Here’s the twist. Pekić’s political beliefs and those of the current government led by the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS) are in direct opposition. Key members of the current government, including the newly elected President Aleksandar Vučić, were also in power during the crisis period of Slobodan Milošević’s rule in the 1990s. The criminality of their reign was one of the reasons why many people took to the streets in massive protests during those years. These protests ultimately led to the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS) coming to power in 2000, of which Pekić’s Democratic Party was a major member. Vučić himself has struggled to portray himself as pro-European and committed to Serbia’s EU integration, while continuing to use every opportunity to emphasize the special importance of the Russian-Serbian friendship.

In addition to representing the Serbian government’s often revisionist interpretation of history, the statues of Belgrade can also be viewed as a means of claiming ownership of historical figures in nationalist custody battles with neighboring countries. The statue of Pekić was announced back in 2015 together with statues of Gavrilo Princip and Nikola Tesla. Today, Tesla has three monuments in Belgrade: one near the faculties of Architecture and Electrical Engineering from 1963 (a replica of the Tesla statue in Niagara Falls), another unveiled in 2006 at Belgrade’s Nikola Tesla airport, and the most recent near the temple of Saint Sava in 2016. (New statues of Tesla have recently sprung up in Novi Sad and Užice as well). Apart from his enormous popularity in the country, it seems that the overproduction of Tesla’s image also serves to assert his Serbian origins in the country’s ongoing dispute over Tesla’s nationality with Croatia, which claims that Tesla is in fact Croatian.

Turbo Sculptures

In December 2016, Belgrade city officials made a baffling announcement: a bronze Andy Warhol statue would be erected in Belgrade for no apparent reason at all. The Warhol statue, as reported by the Serbian media, was a gift from ex-Fimske Novosti director Vladimir Tomšić. Belgrade would become the third city in the world with a statue of Andy Warhol. One of them is located in the small city of Medzilaborce, Slovakia where the artist’s parents were born. The other was unveiled in 2011 at the site of the pop artist’s famous “Factory” in Manhattan, where the majority of his silkscreens and screen tests were made.

Originally, it was announced that Belgrade would install its own Warhol statue on February 22nd, 2017 — the 30th anniversary of the artist’s death. What would make Belgrade’s Warhol statue different from the rest (other than the fact that Warhol has no connection to the city whatsoever) was that city officials promised that Belgraders would themselves get to decide on the statue’s future location, with several possible sites suggested in advance.

This seemingly democratic procedure is an exception that proves the general rule: citizens are not included in the decision-making process about public monuments or the utilization of public space. (One notable exception is the Beogradski čitač, which did stir public opinion about how a sculpture could promote reading and literature). While city officials announced that citizens of Belgrade would be given the opportunity to decide on the location of the Warhol statue, residents of the city were not consulted about the government’s far more invasive three-billion-euro Belgrade Waterfront mega-project. The UAE-sponsored development will see part of the area along the Sava River transformed into a sprawling residential and commercial center, replete with thousands of luxury condos, a Burj Khalifa-inspired tower, and the largest shopping mall in Eastern Europe. Resistance to the mega-project and the absence of citizens in the decision-making process triggered the largest protests in Serbia since the fall of Slobodan Milosevic. With this in mind, the seemingly “democratic” choice granted the citizens of Belgrade about placement of the Warhol statue seems insignificant.

But why would the Serbian authorities decide to erect a statue of Andy Warhol in the first place? The video artwork Turbo Sculptures (2010-2013) by Aleksandra Domanović attempts to address just this sort of question. Domanović compares turbofolk music and a new “turbo” production of pop culture sculptures in the ex-Yugoslav republics.

“Unlike war memorials, these public monuments do not refer to a common history of a specific site or occurrence; they are based, instead, on modern popular culture that knows no genius loci,” Domanović says. “Instead of war heroes, who would have been immortalized by classical monuments, local authorities now decide to eternalize Hollywood stars and heroes of the Western world in bronze.”

The reference to turbofolk music in this context “suggests that [these] sculptures remain neutral in the turmoil of political disputes,” Domanović explains. “In the end, Turbofolk became a regional pop music that was not only composed of music from the performers’ own regions; it also captured folk music from other countries, including in the Middle East and the Mediterranean area.”

So-called “turbo sculptures” and regional pop music are therefore part of a similar genre, one that “addresses both the exoticization of local craftsmanship and the alienating function of high art’s seemingly universal modernist idiom.”

Of course, Belgrade is not the only city in Serbia or the region to feature such puzzling statues. The Serbian city of Žitište erected a statue of Rocky Balboa by Croatian artist Boris Staparac in 2007. Later that same year, in the nearby village of Medja, officials raised a statue to native son Johnny Weissmuller, an actor who portrayed Tarzan in a number of films. Some criticism of the sculptures has focused on their figurative nature, as well as the consistently conservative, male and “macho” choice of subjects. The new statues have also been criticized as a cheap means of promoting tourism. The 2011 edition of Lonely Planet listed the Rocky Balboa statue in Žitište among its “top ten most bizarre monuments on Earth”.

The Presidential Election in Serbia: A Light at the End of the Tunnel?

Some of the region’s statues, such as that of Bob Marley in the Serbian city of Banatski Sokolac and Bruce Lee in Mostar, have been presented as a way to connect people divided by war and nationalist rhetoric through the supposedly unifying force of international popular culture. But these monuments have no local reference point.

As Andy Warhol once said, “I am from nowhere.”

With the exception of Kosovo, which features sculptures of US presidents, most new sculptures are of film characters and international celebrities.

Escape from Memory

The main criticism of these sculptures is that they are escapist, turning away from the horrors of the Yugoslav wars and the realities of contemporary politics. These new statues are merely seen as a means of promoting tourism or international investment rather than memory. They do not deal with relevant events or figures from Serbia’s more recent history. Irina Subotić, an art historian, says that these statues provide no progressive approach to the future: “What we have today is absolutely retrograde, empty rhetoric in which not even the artists making these kinds of monuments believe, much less those passing by. Only those whom those monuments depend on believe in them”.

But contemporary art may also be inventive enough to escape the classical heritage of monument-making. Different and innovative approaches to public memory and space are possible. Last year’s exhibition Monuments and ideas by art historian and curator Irina Subotić at the Cultural Center of Belgrade, provided a glimpse at those alternatives. The work of local artists, ranging from sculpture to media art, was on display. Monuments and Ideas emphasized that its target audience and objective were “those who make decisions on monuments, to make them think – why is there such a graveyard [of monuments] on the streets of our city, our region”.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)