In the nearly three years since the Ukraine crisis began, the search for the “Russian threat” has racked Europe. Politicians, journalists, activists and, indeed, ordinary people are categorized in terms of their pro- or anti-Russia stance or connections, often with little detail as to what these might actually entail. In recent months, this paranoia has escalated, with western establishment voices claiming that the Kremlin seeks to destroy the European Union and manipulate the US elections.

Clearly, the Russian state is on the move. But if we are to discuss the problems facing Europe cogently, we should be wary of the difference between perception and reality — and our own biases.

While Europe’s establishment calls for national unity against external threats (strengthen the status quo!), what we should tackle is the root causes of far-right radicalism and the appeal of right-wing populism in Europe.

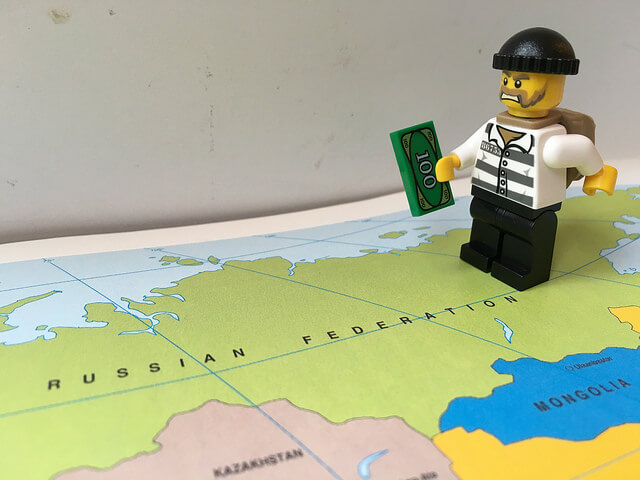

Europe’s new paranoid vision is the product of several factors. First, Russia’s deployment of hybrid war, whereby propaganda, unidentified troops, arms and cyber warfare coalesce to destabilize and confuse. Undoubtedly, Russian state actors capitalized on the power vacuum in eastern Ukraine in 2014 using these methods, and continue to seek influence within Europe by a variety of means, not least of all party sponsorship, promoting anti-establishment views and financing infrastructure projects.

The very term “hybrid war”, however, plays on Europe’s long-born fears of its other — Russia doesn’t play by the rules. The western media’s reaction to, for example, RT and Sputnik has sought to sensationalize the threat posed by Russia (amplifying the otherwise minor impact these outlets have). In fact, this overreaction contributes to the very thing Putin wants you to think: Russia is a world power.

Second, the polarization generated by hybrid war plays on the west’s deep-seated institutional and public memory of the Cold War. Here, sensationalism and influence-seeking align in media, think tanks and the military to ensure clicks, legitimacy and funding. Want punters to buy your newspaper? Run a headline like “Putin wages propaganda war on UK”. Want more public funding for new military technology? “Leak” a House of Commons defence committee report (otherwise freely available) on Russia’s hybrid threat to the United Kingdom, and let the press do the rest (Private Eye 1425). At the same time, this memory helps the media portray Russia much like any other “foreign country” — through stereotypes, and, in the case of Russia, through Putin.

Together, these make up the new Cold War paradigm. This vision organises our view of European politics around the ultimate, but misleading cui bono “Does Putin benefit?” This fact is crucial to understanding how the “Russian threat” can be instrumentalised for political gain across the continent. Whether you’re trying to discredit your political opponents or build institutional authority for a pro-European think tank, you can always claim that your opponents’ actions will mean one thing: “Putin wins”, and therefore “we lose”. It is precisely this externalization of threat that impedes Europe’s introspection.

The alleged rise of a Kremlin linked far-right network across central and eastern Europe is a case in point. There’s no doubt the nature of these linkages clearly demands further investigation. The Kremlin, however, did not instigate or start these movements —it amplifies these groups’ influence for its own power projection. The prospect that Russia is “controlling” these groups merely reflects the presumption that the west, having defeated fascism and communism, is now liberal (how else could they get there?). The “infection”, as ever, comes from without.

But while Europe’s establishment calls for national unity against external threats (strengthen the status quo!), what we should tackle is the root causes of far-right radicalism and the appeal of right-wing populism in Europe — the rise of tabloid politics, widespread economic insecurity and deepening class antagonisms.

This is not an apology for the Putin regime, which has successively disenfranchised its citizens, but a call to realise that we face a common challenge — Europe’s struggle to stay afloat is linked to the fight for a Russia that is economically and politically just.

We should, for example, recognize that the Russian regime is deeply neoliberal. As Ilya Matveev argues, since the second Putin presidency, the Kremlin has sought to balance its own economic failures with austerity measures, corralling a potentially rebellious electorate behind the tricolour with slogans of national revival. Sound familiar?

Russia’s adventures in its “near abroad” are relevant here, too. The annexation of Crimea and the continuing destabilisation of eastern Ukraine have not only bumped Putin’s (falling) approval ratings since 2014, but have also served the interests of the oligarchy.

Unsurprisingly, it is the European states with the deepest economic ties to Russia, such as Austria, Germany and France, which are now witnessing lobbying efforts from big business to remove the sanctions against Russia.

Thus, if you trace the confluence of Russian elite economic interests in Ukraine prior to 2013, as Karen Saunders and Boaz Atzili (and others) do with aplomb, you see how foreign policy and elite interests intertwined in 2013-2014 to create a perfect storm. Throughout 2004-2013, big players in Russian and Ukrainian metals, mining, military-industrial, chemicals, gas and oil worked together, with Russian oligarchs buying significant stakes in Ukrainian enterprises, such as the gas-transit-chemicals nexus controlled by Dmytro Firtash, and politics.

When Yanukovych’s rejection of the EU Association Agreement in 2013 misfired, the Kremlin, together with the managers of Russia’s business empire, saw that any future agreement and regime change would damage their finances. On the one hand, the agreement would introduce transparency, competition and standards regimes, and, on the other, the switch of power in Kiev would empower a rival clan. No surprise they gave the go-ahead in the Donbas a few months later. And they won big, too: Russia’s oligarchs feasted on Crimea’s spoils by “nationalizing” their rivals’ property in late 2014.

As the Panama Papers show, the Russian regime does this while capitalizing on the western elite’s offshore financial structures for its own private aims. The Kremlin’s ability to “infiltrate” European economies through infrastructure deals (buying influence and understanding at the same time) is predicate not only on its own readiness to stump up the cash, but the desire on the part of European politicians to do these deals in the first place.

Unsurprisingly, it is the European states with the deepest economic ties to Russia, such as Austria, Germany and France, which are now witnessing lobbying efforts from big business to remove the sanctions against Russia. Meanwhile, Russian, Ukrainian and European companies continue to profit through the system of hybrid-war-and-peace in eastern Ukraine.

Here, then, is Europe’s real weak point — our politicians’ outsourcing fetish and the nepotistic deals that lurk behind it. After all, in the boardrooms and business hotels of Europe, cash talks louder than values.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](https://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)