Editor’s note: This is the extended version of an article that first featured in The Guardian, 4th June 2014.

[dropcap]R[/dropcap]evolutions don’t happen under total oppression. To stand up against authoritarian rule and organise themselves people need some fresh air. It does not have to be much: a few inches of freedom to think and communicate may be sufficient to start an avalanche. That was the case in Poland 25 years ago, when one free newspaper and a few free trade unions triggered deep social and political change – something we like to call a “peaceful revolution”. Not so much blood, a lot of talking, (almost) no revenge afterwards. But there was something more; something that stands out of memories and interviews with those, who were determined enough to rebel: common and deeply disturbing experience of mass surveillance.

The rule was simple: if you were not with us, you were against us. In order to find out who really was “with us”, everybody was under some form of surveillance. Secret police tried to install its spies on every corner and in every house. Most of them were not professionals: intelligence network relied on neighbours that spied on neighbours and work mates that spied on one another. Of course, there were mistakes, but it wasn’t an issue. Everybody who once became a suspect, had a good chance of experiencing prison, tortures, isolation from family or blackmailing. It was not so much about obtaining information – mass surveillance under communist regime was more about breaking people and making them obedient.

[quote align=’left’]How is that possible that until now Polish citizens haven’t heard a word of explanation from their democratically elected representatives with regard to Snowden’s allegations?[/quote]Poland is celebrating 25 years of what we like to think of as free and democratic state. We would like to believe that it’s no longer young democracy; that our legal and political institutions have gained this sort of maturity that is expected from adults. Reasoned choices based on evidence, not emotions. Long-sighted policies. A sense of responsibility for those who depend on the state for their wellbeing and legal protection. Full recognition of human rights, including the right to dignity, presumption of innocence and unconditional prohibition of torture. We have all that – in political strategies and official documents.

In the aftermath of most recent Snowden revelations – indicating that Poland cooperated with US intelligence and delivered vast amounts of telecommunication data (possibly about own citizens) – the anniversary of our “freedom” feels sweet and sour. How is that possible that until now Polish citizens haven’t heard a word of explanation from their democratically elected representatives with regard to Snowden’s allegations? We still don’t know the answers to basic questions: what was the purpose of Polish – US cooperation; who was the target; what sort of data was intercepted and why?

It is not the first time when Polish government fails in explaining serious allegations of human rights abuses – the same evasive strategy was adopted when media revealed its involvement in US secret renditions programme. It took eight years to bring a legal case against Polish government to the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg and expose what happened in a military base in Kiejkuty. What became obvious after a number of journalistic investigations and independent reports (e.g. Dick Marty’s report published in 2007), is still being denied by former and present state officials across political spectrum.

It is true that democracy and rule of law cannot be achieved once and for good. It is a work in progress, with new challenges after every turn of the road.

But at the same time there are things that cannot be accepted in a regime that claims to be democratic;

redlines that – once crossed – undermine the very essence of what “rule of the people, for the people” should be about. How many of such redlines have been crossed by Polish government and like-minded decision makers around the globe in their secret cooperation with US intelligence and their failure to respond to Snowden’s allegations? What has been sacrificed for nothing more than political assurances that it was necessary for our security? There are at least three serious suspects: human rights safeguards, accountability and transparency.

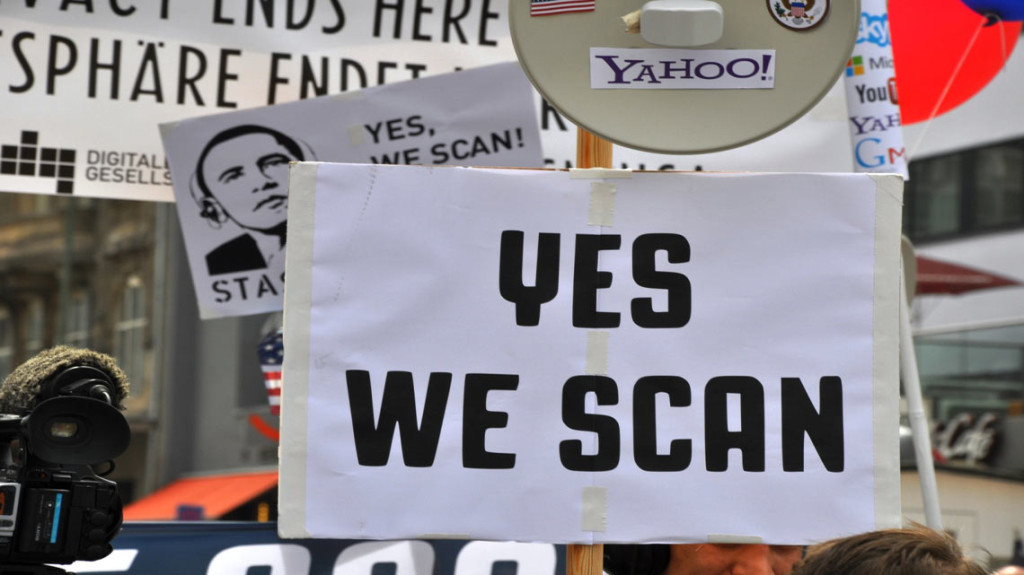

What we felt that had been happening under the label “war on terror” long before Sonwden’s leaks, became now evident: secret cooperation of intelligence services is not about fighting terrorism; mass, pre-emptive surveillance of innocent citizens is a rule – not an exception. Both the amount of data involved and the features of secret surveillance programmes leave no doubt in this respect. It also became evident that European governments – including Poland – cooperated in this effort. Here it is: a missing link between European law that introduced mandatory telecommunication data retention in 2006 and US programmes of mass surveillance. Measures, which human rights advocates across Europe have been fighting for last seven years, turned out to be part of something much bigger and much more disturbing.

Targeting innocent citizens and collecting data “just in case it may turn out to be useful” brings us 25 years back – to the times when secret police wanted to break and control people more than it wanted to collect intelligence. Such approach clearly cannot be reconciled with the concept of fundamental rights, in particular with the right to privacy and presumption of innocence. This position has been reinforced by the Court of Justice of the European Union in its recent judgement that declared Data Retention Directive “invalid from the beginning” because of insufficient human rights safeguards. Yet, our democratically elected representatives seem to believe that blaming it all on “terrorists” remains a plausible explanation and a compelling reason for citizens to keep quiet. If it works for law enforcement and intelligence, it must be good for public security.

[quote align=’left’]Edward Snowden summarised this subtle process of eroding democratic institutions in one simple sentence: government seized power to which it is not legally entitled. [/quote]Power balance between those citizens, who don’t want to keep quiet, and their elected representatives has been disturbed to the extent that both political and legal accountability simply doesn’t work. Between election campaigns we are left with mild and evasive public debate, where silence remains the easiest answer. During election campaigns we hear that human rights have to be “balanced” because of economic crisis and pressing external threats. Not a single politician will take a risk of taking such conversation further and explaining why it is so difficult to ensure at least minimum safeguards reminded us by the European Court of Justice. After all public debate is about emotions, not legal arguments. Decision makers learn quickly from cases such as CIA renditions and the failure of Polish authorities to prevent torture in Kiejkuty: as long as they have some political influence, there will be no accountability.

Institutional checks and balances cannot work without sufficient information. Therefore, the main obstacle that we now face in demanding more accountability, is secrecy. It is commonly accepted in Polish political debate that if a certain activity is related to national security, it should be kept secret by default. Such reasoning – reinforced by lack of clear and authoritative jurisprudence – makes any form of supervision over intelligence community extremely difficult, if not impossible. Even parliamentary commission that has access to secret information and is entitled to discuss intelligence matters, failed to question and explain Polish involvement in US mass surveillance programs. Or decided not to tell citizens that it did.

Edward Snowden summarised this subtle process of eroding democratic institutions in one simple sentence: government seized power to which it is not legally entitled. How much more power are we prepared to give away before we conclude that our much cherished democracy has turned into a facade?

Editor’s note:

This is the extended version of an article that first featured in The Guardian, 4th June 2014.

Photo credits:

CC – Flickr.com. Some rights reserved by Digitale Gesellschaft

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)