The footbridge is narrow, with a high fence on both sides. From Monday to Friday, Grzegorz walks it twice a day. Cars pass underneath his feet; the sun has just risen. He looks ahead, at men and women who, like him, are walking towards Gate Six.

The Skoda Factory is the very heart of Mladá Boleslav, Czech Republic. It occupies one-third of the city’s area and employs over 15,000 people. Czech teenagers make plans to work for the company in the future: there are schools at Skoda – a vocational and technical school, and there is a university outside. If you graduate from the Skoda School, you are guaranteed a job at the factory. Many residents also work in dozens of plants on the outskirts of Mladá, which supply parts for the production of the company’s cars. The number of foreigners in the city has been growing for several years now: Slovaks, Poles and now also Ukrainians. There is even a Facebook group “Poles in Mladá Boleslav” with nearly 700 members. Employment agencies lure them here with promises of much higher wages than in Poland. Online advertisements offer 31,000 CZK (over 5,000 PLN) for a paint shop employee, but often the salary turns out to be lower.

During the week, Skoda’s factory operates non-stop, as do most of its subcontractors.

When small groups of people dressed in white overalls move through the streets of the city, it’s a sign that a new shift is about to begin at the factory.

FIRST SHIFT

Grzegorz smokes a cigarette in front of the gate. He takes out his pass. ‘Beep-beep’ — the machine sounds and the gate opens. He goes to the other side. Here, the compact mass of workers is divided into several thinner threads stretching in different directions. From the gate to Grzegorz’s welding shop it is a three minutes’ walk. It’s 5:30 in the morning. Before he arrives at the assembly line at 6.00 a.m., he puts on a pair of white and green work pants in the changing room. From his personal locker, he takes out special boots with reinforced tips that protect his feet from being crushed. He puts on a blue shirt with short sleeves and the logo of the international recruitment agency Man Power. Under his arm, he holds sleeve covers that reach from the wrist to the elbow and fingerless gloves. The latter not just to protect his hands from cuts but also help him feel even the slightest anomaly on the car’s body. In his pocket, Grzegorz places protective glasses, an air filter mask, and earplugs. He won’t put them on until he gets to the assembly line. Now he’s got time for a quick smoke. From the corner of his eye, he sees that night shift workers go to the changing room, which means “the line is ready”.

At 5:50, he reaches his workplace. Before the foreman gives the signal and the line starts, Grzegorz readies the work station. On the table, he lays out a grinder, several files, and a special pencil to mark faults on the body. A colleague next to him does the same thing. Grzegorz is responsible for checking the left side of the car body and half of the roof, the coworker does the right side. In the brigade, apart from Grzegorz, there is one Hungarian, two Slovaks and two Czechs. There are six brigades on the whole shift. Everyone’s doing different things.

A bell sounds in the hall – a signal that the line is about to start. Grzegorz stands almost at the very end. When a car, or rather its bodywork, rolls from the line into Grzegorz’s station, he has only 45 seconds to check for irregularities on the right side. The eye won’t notice all the details, which is why in his work Grzegorz relies on his hands. He moves them methodically over the metal surface. When he feels a dent where there shouldn’t be one, there’s no time to lose. If the flaw is significant and cannot be fixed within 45 seconds, Grzegorz marks the spot with a special pencil and the car passes on. Somebody’s going take care of the vehicle when it rolls off the line. But such a solution does not always work because there are only 15 spots at the parking lot for defective car bodies. Grzegorz uses the pencil as a last resort. Mostly, he prefers to fix the dents himself. He takes out the files and the grinder. If he feels that the work will take him an extra 15 seconds, he stops the line. But each pause results in another delay. Grzegorz knows that the foreman is not happy about it. There is a quota that needs to be done: during one shift, an average of 450 bodies are checked.

The car bodies arrive at Grzegorz’s welding shop in parts. They’re cut from enormous metal sheets by robots, then put together into the shape of a bodywork. In the end, people at the line attach doors, trunks and other parts of the vehicle.

“At first, I didn’t understand where the flaws came from, the computer does everything, after all. But the truth is, we’re at the end of the technology chain. You’re installing the door and push it with your knee – you have a dent. But if everything could be assembled by robots, I wouldn’t be needed, I guess,” he says.

Grzegorz has not lived in Poland for seven years. Through a job agency, he has already cleaned crabs in the UK, worked as an electrician in Germany, and then went to Switzerland and Austria for a short time. He’s worked at the Skoda factory for a year and a half. He lives with other Polish workers in an apartment located just 300 meters from the plant. Before that he used to live in houses where he wasn’t sure he’d still find his things in his room after coming home from work. After seven years of wandering, he appreciates the benefits. The agency provides him with cleaning products, clothes, “a bit of this and that”, which makes him feel like that someone is taking care of him.

“Besides, when I get ill, I have sick leave,” he points out and adds, “But it is not worth it to get sick. In Czechia, the first three sick days are unpaid, then you get 60% of your salary. So, I don’t get sick. That’s an interesting thing – I used to get sick in Poland. But I had a wife and kids there. I had a lot to do. Now even when I’m sick I go to work. Sometimes with a cold and a fever, but I manage. But I never ride a bike if I’ve had some beer, so I won’t break my legs, because that would be a problem. I used to make plans, now I don’t.”

On the line, the color of your shirt marks who you are. Grey means employees of Skoda, green means foremen, who are mostly Czech and also work for the company, blue means agency employees, such as Grzegorz.

There are about thirty employment agencies in Mladá Boleslav, which has a population of 50,000.

“Not all of them are trustworthy. Some of them exploit people,” says Petra Baborovska, an activist from Centrum Pro Integraci, organization established to help migrants, several thousand of whom live in Mladá.

Agencies offer jobs not just at Skoda, but also dozens of local firms. Companies are reluctant to broadcast their cooperation with agencies. During a tour of the Skoda factory, the guide takes the group to a hall where employees assemble car interiors at the line. Only a handful of blue T-shirts flash among the grey and green shirts.

“These workers came as substitutes. They’re not employees of Skoda, they’re employees of an employment agency. Thanks to them, we are able to fill vacancies if one of our employees gets ill,” explains the guide.

But in the halls where no one is allowed uninvited, there are many more “blue” shirts. Yes, they do sometimes substitute for someone, doing overtime. But each one of them also works full time. Grzegorz estimates that at his welding shop the “blue” ones make up about 30% of the employees. The international employment agency Man Power has a monopoly. Grzegorz found an ad on the Internet. At that time, he had been working for two and a half years in the Czech town of Liberec. First, it was air conditioning for Japanese cars, then assembling sunroofs. At that time, he was also employed by an agency, albeit a Czech one. He was fed up with living in a workers’ hostel, and Man Power guaranteed help with renting the apartment and financing it, and, first and foremost, promised much better money. Grzegorz signed a contract for a year with them.

Theoretically, after a year every agency worker should be employed by Skoda. But six months ago, Grzegorz renewed his contract with the agency. Unlike factory employees, as an agency worker, he can take overtime and thus earn more. Four days a week he works eight hours, and on Fridays, he takes two shifts and spends sixteen hours on the assembly line: he gets in at 6 a.m., gets out at 10 p.m. He earns about 30,000 CZK a month, which is about 5000 PLN. The only problem is the agency can fire him without notice.

“I’m not worried. There’s plenty of work in Mladá. If I get fired here, I’ll find something in a flash. I’d rather earn more than feel secure,” he declares.

SECOND SHIFT

“Got some change to spare?” Basia hears in Polish when she comes home after her shift. She asks the stranger where he’s from and what happened to him, why he’s begging for money in the street. He came from Opole, worked at Skoda, tested cars, crashed one, got thrown out. Basia is from Opole, too, and knows that sometimes in life things can just go wrong. She digs up some change from her pockets, although she doesn’t really believe the man’s story. At Skoda, it’s very difficult to get fired. If you can’t handle something, they transfer you to another job. However, there are those who come from Poland hoping to earn a lot of money, even though they have never worked in a factory before. They are not prepared for the hard work. They collect their first paycheck and then they don’t show up anymore. Drugs are also a problem, and methamphetamines are particularly easy to get as they are sold on the plant premises. Basia herself witnessed security guards search workers’ lockers; she was also asked to take an alcohol level test. Those who have given up or been fired from work often live in the streets, parks and makeshift shacks. They do not return to Poland.

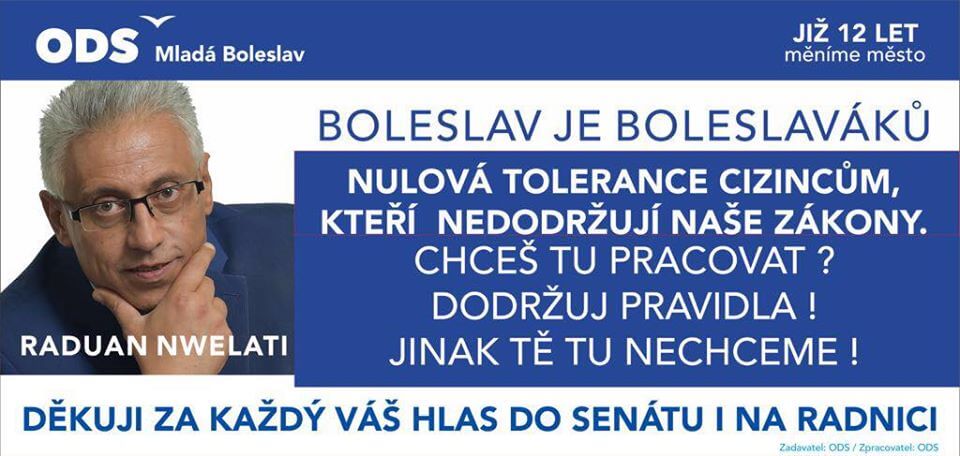

In 2018, Raduan Nwelati, Mladá’s mayor famed for his anti-immigrant views, launched special police patrols composed of Polish and Czech officers, tasked with fighting crime, controlling the city and getting rid of Polish people experiencing homelessness. “Boleslav je Boleslaváků (Boleslav is Boleslav). No tolerance for foreigners. Do you want to work in our town? Adapt or go home!” proclaimed re-election posters for the city’s mayor — a member of the far-right wing of the ODS party.

Basia and her husband Maksym plan to stay in Mladá, at least for a few years, so they have tried to adapt. They have been looking for an apartment for a long time, which is not easy, because after all the incidents in recent years, real estate owners are reluctant to rent to Poles. In the beginning, they were lucky to get a room for just the two of them. It is difficult to find accommodation for a family in workers’ hostels. However, they agreed to pay extra to cover the third resident’s portion of the rent and so they could live without a roommate. The room served as a bedroom, a living room and a dining room. On the windowsill, there were stacks of rice bags and tea. Their belongings did not fit into the cabinets so they laid them out carefully around the bed in the middle of the room. They hung a plasma TV on the wall and placed a cage with a rabbit on the floor, in a corner. Basia tells us that a small cooker connected to a pipe protruding from the wall, with a waste bin next to it, served as the communal kitchen. The washbasin in the bathroom doubled as the kitchen sink, and everyone had their own pots and pans. Basia mentions that living together with so many people was an exhausting experience. Luckily, she knew how to keep her housemates in check. When someone was partying too loudly, she would yell once or twice out on the staircase and there was silence. Nobody protested.

The first one to come to Mladá was Marcin, Maksym’s brother. At Skoda, he works in a warehouse, drives a forklift truck. In the future, they plan to bring their mother to Czechia, because she is seriously ill and can’t support herself on her Polish pension. Marcin is going to help financially and the Czech health service is going to take care of her.

Back in Poland, Basia used to work in a grocery shop and Maksym did not have a job because he was on disability allowance.

“Fortunately, in Czechia, it doesn’t matter,” Basia says, “as long as you can walk and move your arms, you can work. Our problems started when I opened a bar in Opole,” she adds. In the morning, she worked in the shop, in the evenings in the bar, but she didn’t have many customers. And when someone did come, they would buy little and stay long. To open it, Basia took a loan that she couldn’t pay off. Together with Maksym she searched the Internet and found an advertisement for the Czech employment agency DP Work. The company offered them a job in Mladá Boleslav. At Faurecia, a company manufacturing interior fittings for Skoda cars. 100 CZK an hour sounded good. They closed the business and left, in order to be able to send 1,000 PLN to Poland for the next three years, every month, to repay the loan. Once they arrived, it turned out that instead of 100, they would get only 76 CZK an hour. They demanded to be paid the promised wages, but to no avail.

“KOVO trade unions are strong at Skoda, and they protect the interests of workers employed through agencies. In other companies, there are either nor trade unions at all, or no one cares about agency workers. We had no one else to turn to,” Basia says.

After six months, they asked a DP Work agent to find them jobs that would pay as much as the ad had promised. They were transferred to TRW, a company that manufactures seat belts for Skoda. But when Maksym went to work there, the shift manager sent him away, saying she didn’t want any Poles. He worked at TRW for less than two weeks. Basia three. She quit because she wanted to be near her husband. They decided to change their employer. “In Mladá, employment agencies are everywhere, you can come in from the street and ask about an ad,” she explains. Czech agency Zetka found them a job at Benet. They were making chassis components, again for 76 CZK per hour instead of the promised 100 CZK. “But it’s better than sitting around at home,” Basia comments. Because there have been times like that, too. They were even more stressful than the constant search for a well-paid job. Around the holidays in Skoda meant Basia and Maksym’s phone did not ring because the production in cooperating companies also stopped. For three weeks they stayed home, thinking how they were going to get money for the loan installment that month, not to mention rent for the room in their workers’ hotel and groceries.

Now they work for OSSPO, a small company that cooperates with an agency of the same name. Maksym polishes chassis components, Basia is responsible for checking manufactured parts and sending them to the paint shop. The management is nice, it employs people of different nationalities. The couple no longer hears that Poles aren’t fit for work. This time they were promised 110 CZK per hour and after three months they were hired directly by the company.

Some time ago they found a three-room apartment and happily moved out of the workers’ hotel, even though instead of 1,000 CZK they now pay eleven times higher rent and still have housemates. However, the rooms are spacious, the toilet is separated from the bathroom. And, finally, they have a real kitchen.

THIRD SHIFT

Dorota sits at a table in the kitchen, one hand ashing her cigarette into an ashtray, the other stroking her dog. It’s 8:30 p.m. Dorota got up just ten minutes ago. She’s been asleep since 4:00 p.m. because today she’s got the night shift. Work will start at 10:00 p.m. and end at 6:00 in the morning. And so on for the next five days. She doesn’t like weeks when she’s on the third shift. Working at night disrupts her days. Luckily, next week she works mornings, then afternoons and so on. She has to leave in an hour at the latest.

She thinks less and less about the Dorota that came to Mladá three years ago with a small backpack and a great fear of the unknown. The fear diminished gradually, and the backpack has been growing slowly, as she adjusted to Mladá. She left Poland without any regrets. For years she had worked in various plants, handed out leaflets, but employers never offered her anything other than “junk contract”. Sometimes they didn’t offer her any contract at all and Dorota was working illegally. Someone took her on as a substitute several times – shortly before she left, she had worked at Lidl for three months. And then again, she was left with nothing. The temporariness became unbearable. Plus, Dorota had been dreaming of getting out of her toxic relationship for years. She counted the days until her younger daughter came of age. “Then we’ll run away together,” she used to say.

Dorota – to work abroad. Her daughter – to a rented apartment that her mother would pay for with money from her job.

“One day I just walked out of the house. I closed the door and that was the end of my old life,” says Dorota, inhaling cigarette smoke.

Earlier she’d found an online advertisement for a job at Skoda. However, the employer was not the car manufacturer, but a Czech employment agency, DP Work. They promised she’d be earning 20,000 CZK (per month?), plus a rent allowance for a workers’ hostel. Once she arrived it turned out that instead of Skoda, the agency intended to send her to a company manufacturing seat belts. Unfortunately, the wages would be much lower than the advertisement said. What she found in the workers’ hotel, Dorota doesn’t want to remember. She only says that there were no doors in the toilets and the walls were made of cardboard. It took three days but finally, the coordinator from the agency caved and Dorota and a group of Poles were transferred to better accommodation. She stayed there for the next eight months. She refused to accept a lower salary on the first day, so instead of making safety belts, she was sent to Skoda, to the assembly line.

Dorota thinks less and less about that Dorota from Silesia, because now she rents a Czech apartment with her Czech boyfriend, whom she met at the workers’ hostel. She has a Czech indefinite employment contract, adopted a Czech dog and recently took her younger daughter on a Czech vacation to Bulgaria. In Dorota’s idiom, the “Czech vacation” differs from the Polish one in that you go at all, and you can even afford to stay in a comfortable hotel. “Polish vacation”, if it even happened, was always spent in a tent, because it was cheap. It had its charm and Dorota remembers it fondly, but she prefers to have a choice.

She puts out her cigarette and slices bread for sandwiches to work. When she closes the door, her boyfriend slowly gets ready for bed. He goes to Skoda in the morning but works in a different hall, so they will not see each other until after 2 p.m. It takes less time to get from home to the main gate leading to the Skoda plant than later to walk to the hall, where about 200 people report to start the shift. They work in 15-person teams. Half of the employees are women, which is quite unusual because in many halls there are no women at all or just a few. Dorota arrives at her hall in 8:10 p.m. She doesn’t know what she is going to be doing tonight. From a distance, she notices the foreman, who is already waiting with his notebook open. The notebook contains a record of who does what and when on the line. Dorota’s team is made up of Czechs, Slovaks, Poles and one Moldovan. The task of the whole shift is to seal an average of 730 cars. Dorota’s team is responsible for eleven stages of the process. Car bodies that have undergone the first phase of painting arrive in the hall – they have been submerged in a large pool and then sent to the furnace, which hardened the layer of paint. All cars are uniformly gray and will now be fitted with rubber components, foil, and caps in all nooks and crannies of the body.

Today, Dorota starts at the “computer”. When the line launches, Dorota already has a scanner in her hand. She comes up to the approaching car and places the device on a code plate at the front. On the scanner screen, she sees that this Octavia will go all the way to Saudi Arabia, and, in addition to the plastic protection at the back of the body, the buyer has ordered additional sealing of the roof and a number of other improvements. Dorota puts the scanner down and starts assembling the components. She needs to get around the car, and she’s got less than a minute to do everything. After an hour’s work, the foreman takes Dorota’s place and she can go out for a cigarette or to the bathroom. After two hours, the bell rings in the hall – a sign that the line stops and the employees have a 5-minute break. After that, Dorota moves on to the so-called “wagon”. She sits on a chair mounted on rails, in front of her she has plastic boxes – each with different rubbers. Car bodies now pass over her head and she installs the rubbers on the chassis, with her arms up. After two hours, another change. Dorota goes to the end of the line. She puts on a pair of white gloves, looks into every nook and cranny of the body and checks the work of her colleagues. For the past two hours, she has been putting rubber parts on the right side of the body. Out of the eleven positions covered by her team, she has mastered nine. A lot for one employee but she rarely gets bored at work and fatigue spreads evenly throughout her whole body. Dorota is agile and today a minute to complete the task is plenty of time for her; she will still have time to talk to her coworker before the next body arrives. But it hasn’t always been like that. On her first day at Skoda, she was sent to the airbag assembly. She couldn’t cope because she’s too slight and doesn’t have much strength. Her foreman at the time was very surprised when he saw Dorota report to work the following day. He was sure she’d flee like many others before her. But where would she run if it had been to Skoda she had escaped? After three days, she was transferred to the hall where she has been working since. After a year and three months, she became an employee of Skoda, although some of her colleagues have worked under the agency for four years now. For the first few months after the move, she was earning less, but finally, for the first time in her life, she felt safe.

Dorota wants to continue working at Skoda until her Czech retirement. “This is the only place I succeeded,” she says and lights another cigarette.

AFTER WORK

“I started 13 years ago at the welding shop,” says Arek, sipping his beer. He comes here, to Kufel Bar, almost every night. A lot of employees from the Mladá factories meet here. During the week, you can watch a hockey game together, have a beer and talk. On weekends there’s a barbecue, someone brings a guitar or a violin. They all know one another by name and greet new arrivals loudly.

Arek also wants to work at Skoda until retirement and stay in Czechia. He’s been coming here since he was a child, to see his aunt. When he stayed to work, he learned the language easily. He understood a lot, he just had to start speaking. He was never fit to live in a workers’ hostel, so he found an apartment as soon as he could. While still at the hostel, though, he met Petra, who lived in a social apartment in the same building. Now they live together. Petra’s dad worked at Skoda, her brother still works here, and her son goes to school for future workers and trains as a locksmith.

“Most of them begin with assembly,” Arek says. That’s the easiest way to get started. There are chefs, carpenters. In the first months, sometimes years, almost everyone works through an employment agency. If they prove their worth, they are employed by Skoda. Arek started with the simplest job, then he learned more. He was assigned to an experienced employee, who helped him during the first three days and showed what to do and how to do it.

“It’s stressful, but a Pole will manage,” Arek smiles. “Once you’ve been working for some time, you can try to get a transfer to another position. We have an internal computer system where I can check if there are any vacancies in other departments and apply for them. And so, after a few years, I finally got to the steelworks, where I wanted to work from the beginning because that’s my actual profession.

Arek’s been casting engines for a year. Working together with a robot, he fills molds with warm plastic and aluminum, the temperature of which reaches up to 600 degrees Celsius, then cools them down in water and once they are cold enough, he checks the cast forms for any defects. If he finds anything, he’ll have to hammer it out. It’s dangerous at the steelworks, but you work shorter hours than in other sections. Employees are also entitled to more breaks. If the temperature in the factory hall exceeds 30 degrees Celsius, 5-minute breaks turn into 10 minutes, and at 35 degrees, there is a break every hour. In addition, employees at the steelworks finish 50 minutes before the end of the shift. Arek is happy. In Poland, for the same work or harder, for example, casting parts for trains, he would earn 2,000 PLN. He’s got three times as much here. Plus, all benefits for unionized employees. Skoda offers allowances for the gym, massages, holidays. Now, Arek and Petra can go to the seaside, to Greece. He never goes to Poland for the holidays. In fact, he doesn’t go there at all, except for the few situations when he has to deal with something specific. He’s too far away from his hometown of Gdańsk, and his parents are dead. He’s an only child, so there’s no one to visit. Among his Polish acquaintances, he is the minority, though, as most travel to Poland on weekends.

Arek is not afraid of the crisis. He’s survived one already, in 2008. At that time, he was working for an employment agency and was just getting the documents to be employed directly by Skoda. The crisis came and the company stopped hiring people. To become a Skoda man, he had to wait a few more years. But in the end, it worked out. Arek smiles, “If I lose this job, I’ll find another one. I mean, these hands can work.”

**

The Transeuropa Caravans project was funded by the European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (2014-2020). The content of this article represents the views of the author only and is their sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains. Find out more at https://transeuropacaravans.eu.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)