Before the European Parliament elections in 2019, Transeuropa Caravans, a pro-European integration activist group, set out to explore EU countries and “places of struggle and resistance, in defense of fundamental rights beyond borders.”

The project took the activists across 15 countries where the diversity in political landscapes varied as much as the social and cultural expressions they encountered. The group organized five different trips, each with its own emphasis, as part of their project to connect with European citizens beyond national borders; their Scandinavian and Baltic route focused largely on sustainability and climate change: the very definition of a transnational issue.

The Caravans elevated Sweden as a European role model of renewable energy and recycling, but also touched upon a core paradox of contemporary Scandinavian politics: namely youth disappointment. Young climate activists such as Greta Thunberg have labeled the country’s national environmental strategy insufficient, and accused governments of failing to deliver on curbing climate change.

But, despite exasperation with current Swedish climate policy by the younger generation, new waves of climate activism have yet to choose which policies to condone, and which ones to condemn. And while the movement has just organized the largest climate demonstration in history, it is far from obvious what form climate action will take in the future.

At the Forumtorget in Uppsala, Sweden’s fourth-largest city, a group of people of mixed ages protest not far from where Thunberg started her own strike in 2018. Despite the cold Friday temperatures and regardless of the comments from climate change deniers who approach them, people continue their determined protest.

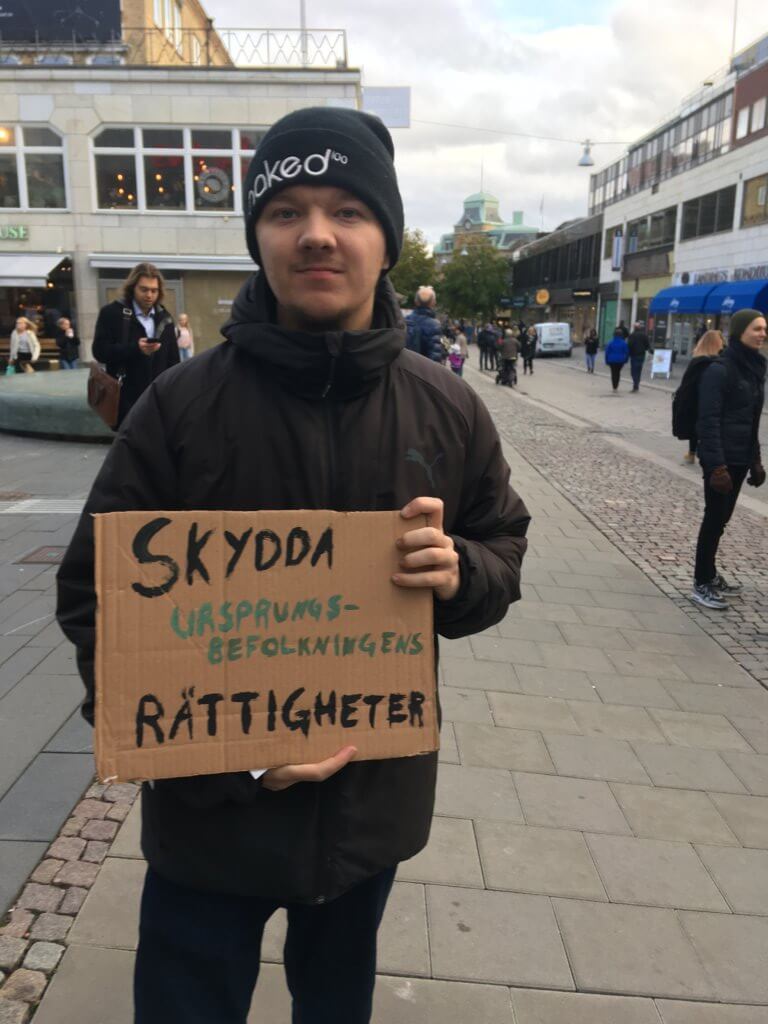

This year, several events, such as massive wildfires that consumed around 25,000 acres last year, have raised the Swedish public’s concern about rising global temperatures. Oliver Haapala, a 25-year old activist, is among those who have only recently gotten involved with Fridays for Future. However, his involvement against climate change began much earlier.

“I’m here for the first time, but ever since I was a kid, I’ve always been more for nature than the world of concrete that we live in,” he says.

When Haapala saw the mass strike two weeks ago, he was filled with joy over the momentum that the strike had created.

“I’ve always been involved, especially to promote the rights of indigenous peoples,” he says. “I’m an individual working for the cause where needed. Considering that only a few years ago not many took this very seriously, it’s thrilling to see so many people are now committed.”

The “Fridays for Future” protests are part of a larger movement inspired by Greta Thunberg who, last September, took her school strike to the next level by deciding to strike every Friday until Swedish policies changed to reach the goal of the Paris agreement: a limit of global warming well below 2 °C.

This year, she was invited to speak at the UN Climate Summit where, on behalf of young people around the globe, she accused world leaders of having “stolen her dreams.” Days later 7.6 million people took to the streets in a Global Climate Strike — a symbol of the climate movement’s dramatic rise over the past year.

In addition to a growth in size, climate activist groups have also increased in complexity. Recently, Swedish environmentalists launched the “Go Climate Strike” app, which allows pupils who wish to strike to report their leave and automatically send an email to the Swedish Ministries of Climate and Education.

One of several climate movements presently growing in Scandinavia, “Fridays for Future” mobilizes mainly young people in strikes and protest outside parliaments and municipal councils. Protesters take a clear stance for mainstream climate science and against policymakers that cling to a business-as-usual attitude and the pursuit of unrestricted economic growth.

One Uppsala protester, 14-year old Vera, says Greta Thunberg was a decisive factor for why she started to strike. Starting last November, Vera tries to be present at the Forumtorget square on Friday as often as she can to make her voice heard.

“I’ve always felt very involved and when I saw Greta and other young people on strike, I thought I should also do that,” she says. “I felt like I wasn’t alone as a young person involved in these issues, that it helps to go out to protest. It’s been tough, but very rewarding.”

Vera talks with a kind of seriousness that is not dissimilar to that of Greta Thunberg.

“For the politicians to go through with the needed change, they have to feel that there is support from the people,” she explains. “We’re talking about a radical change of a kind we have never seen before in the history of humanity, so they need the masses to exercise pressure on them. What we are witnessing right now is that they don’t make the decisions that are necessary and that the science demands.”

Vera also expresses frustration with while climate change as a topic is talked about in science classes, but is very much absent anywhere else like in civics and social science classes.

“We talk about [scientific] solutions but climate change is almost more of a social science issue since it’s about a systemic change.”

Mattias Wahlström — a senior lecturer in Sociology at the University of Gothenburg — thinks it is perfectly reasonable at this point that Fridays for Future pushes so hard on science.

“It makes sense because it’s an effective way of creating a headline, or some sort of mutual goal on which many people can agree,” he says. “It’s a way of pointing to the shortcomings of established politics.”

Walking around the Forum square in Uppsala, the messages on the protesters’ signs vary immensely. What they do have in common is a critique of business-as-usual as well as of contemporary politics.

One of the signs informs the reader that Sweden has already used up its fair share of the entire world’s consumption of fossil energy. The sign Oliver holds says “Protect the rights of indigenous peoples.” Different activists convey different concerns, different strategies, and different experiences about how journalists and passersby have approached them. They all tell diverse stories about their pasts and how they became involved. The heterogeneous character of the movement is obvious.

Vera talks about how big the movement is and that it has become a catalyst for change. She, like the many young people protesting for the first time in their lives on the square, is visibly excited by how the movement has grown but also frustrated with how slow politics is in adapting to what is going on.

“I was in Stockholm at the strike. It was very epic. We were between 40,000 to 60,000 participants,” she recalls. “It was so impressive to see people everywhere that believe in the same things as you do. It gave me a lot of hope and reassurance for the future.”

While Fridays for Future has spread internationally, some environmental movements in Sweden have a more local focus. In Western Sweden, protests led by the group Folk mot Fossilgas (People Against Natural Gas) have targeted Swedegas — which owns the entire Swedish high-pressure gas transmission network — in order to prevent plans to connect a new gas terminal to the Swedish network. Like Fridays for Future, People Against Natural Gas have carried out direct action and mass civil disobedience to press their climate goals; unlike Fridays for Future, their local actions have been against one specific policy choice — the expansion of Sweden’s natural gas dependence.

In September, the group blockaded traffic to and from the proposed terminal site in Gothenburg for 12 hours. The protest was successful in garnering public attention and on October 10, the Swedish government announced that it would not grant the project a license to connect into the wider Swedish energy network.

Local movements like, People Against Natural Gas, which focus on direct action, Wahlström argues, might beneficially complement larger national and international movements.

“What we can see right now in the climate movement is a success in part thanks to Greta Thunberg, but also because movements like XR (Extinction Rebellion) have managed to push for ongoing activism even at times when there are no ongoing high-level meetings,” he explains.

However, protest participants, like Vera, are not without critiques for the movement.

“One should come here for hope, and to remind oneself of solutions and successes,” she says. “[But] I would say that communication is Fridays for Future’s biggest challenge. Since it is a flat organizational structure it can become difficult to make democratic decisions that are anchored with everyone. Because it is so difficult to make decisions as it is now, it’s also hard to lift the things that one might want to change.”

Yet others, like Haapala, see decentralization and a lack of concrete involvement in policy as the movement’s strength which helps mobilize a broad base of people.

As an expert on the narratives of the climate movement, Mattias Wahlström agrees with Haapala. He compares Fridays for Future to Swedish environmental organizations that have worked closely with the executive and legislative power and argues that organizations that become highly institutionalized by cooperating with the political establishment risk losing their radical edge.

What is clear to everyone present is the movement’s momentum, as well as the opportunity to continue to grow. As Fridays for Future, and climate movement as a whole, gets bigger, more people will be drawn to mobilize. One important question that remains to be answered, however, is what the movement’s stances will look like once-radical policies are put into place.

As Mattias Wahlström points out, possible solutions to the political goal of remaining under 2 °C of global warming may interfere with different environmental interests. For instance, questions of where minerals for solar cells should be mined or whether to rely on nuclear power are likely to become even more pressing as governments are forced to take a more active role in curbing climate change.

According to the Swedish Energy Agency, Sweden tops the EU with 54 percent of its energy coming from renewable sources, but 80 percent of the country’s electricity production comes from hydroelectric and nuclear power — both controversial among environmentalists. As policies develop and coalitions among protesters form, these mass movements are likely to face tough decisions on the political path ahead.

**

An earlier version of this article mistakenly described Mattias Wahlström as a climate protestor. He is a sociologist and an expert on the narratives of the climate movement.

**

The Transeuropa Caravans project was funded by the European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (2014-2020). The content of this article represents the views of the author only and is their sole responsibility. The European Commission does not accept any responsibility for use that may be made of the information it contains. Find out more at https://transeuropacaravans.eu.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)