Despite all expectations, or perhaps precisely because these were too high, Aki Kaurismäki’s The Other Side of Hope, “a European comedy about refugees” as it was dubbed by Deutsche Welle, did not receive the Golden Bear for Best Film at Berlin’s International Film Festival. The prize went instead to the Hungarian director and screenwriter Ildikó Enyedi for her film On Body and Soul (Hungarian: Testről és lélekről).

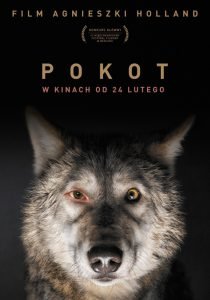

Another Central Eastern European film, Agnieszka Holland’s Spoor (Polish: Pokot) received the Silver Bear “for a feature film that opens new perspectives”. But the crucial parallel between the two films lies less in their region of origin than in their strikingly similar opening scenes. In both films, as soon as the lights go off and the screen ignites, the spectators, crammed in their seats, suddenly find themselves out in the open — in a forest and among deer.

Body and soul

Setting a sharp contrast with the animals that roam freely, Enyedi’s workplace romance places its two main protagonists in a Hungarian slaughter house. Endre (Géza Morcsányi), the enterprise’s financial director, a timid and rational man, is attracted to Mária (Alexandra Borbély), who was recently hired as a new quality controller. But Mária’s reclusive conduct, her almost machine-like memory and attention to detail soon estrange him, as they have already done the rest of her new colleagues.

Film still from On Body and Soul (© Berlinale)

Unable to connect to their emotions, both Mária and Endre put their physical spontaneity on hold. The two would not have stood a chance of getting closer physically had they not got a chance to discover an uncanny connection between their dreams. “This pushes them to step out of the comfortable and safe cage of a life, in which they walled themselves off from others as well as from themselves,” Enyedi told reporters at a press conference.

Passing through security checks before my budget flight back from Berlin, my mind couldn’t help going over the frank images of the industrially optimised processing of cows in On Body and Soul.

“We keep cows in austere, narrow places, where they live miserably only to be killed and eaten. Unlike deer — their free siblings — they cannot lead a full life,” said Enyedi. “Full life does not mean happy life, though. It is just that I feel I was deprived of the beauty and the mystery of birth, love, death. Most Europeans seem to be unable to fully live and cherish these simple moments that we share with the whole of mankind; our culture does not give them space, does not respect them. I have to admit that giving birth to my children in a hospital I felt a bit like the cattle in our film.”

The film’s poetic camerawork weaved with daring in-your-face visuals, subtly plastic acting and intelligent insights well compensates for a few easy-fix plot spots. And I’m sure the film will leave nobody untouched, both sensually and intellectually.

The animal and the human

Moving between the genres of thriller and comedy, Spoor tells the story of Duszejko (Agnieszka Mandat), a charismatic retired engineer, feminist, vegetarian, and astrology enthusiast. She lives in the Polish countryside with her two female dogs and fights the local patriarchal customs based on hunting, money, religion, etc.

One day Duszejko’s dogs go missing, which sets in motion a series of mysterious deaths and a trail of male corpses: a hunter, a poacher, a violent crook, a corrupt policeman and a priest that claims that animals don’t have souls. She comes under suspicion.

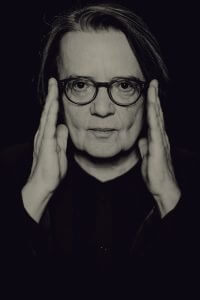

Agnieszka Holland (Photo: Jacek Poremba / Berlinale)

Variety magazine’s unceremonious review called the renowned Polish film and television director and screenwriter Agnieszka Holland, who began her career under Krzysztof Zanussi and Andrzej Wajda, and even directed several episodes of The Wire and the House of Cards, “an unreliable narrator”. I thought it entirely missed the point of the film, not having understood the political context in Poland, in which the film has been produced. I felt responsible for correcting the wrong and went to see it myself.

Now, I must reluctantly agree, at least in part, with Variety’s description of Spoor as a “murky and disjointed mess, held together not so much by what happens as by a vague atmosphere of obsession”. In any case, I do not understand what new perspectives the film is supposed to have opened, according to the jury.

Nevertheless, I could identify with the film’s obsessive and somewhat helpless rage at the face of the reactionary developments under Poland’s new government, epitomised by the infamous remark by Foreign Minister Witold Waszczykowski, resenting the “new mix of cultures and races, a world of bicyclists and vegetarians”.

The Minister of Environment, Jan Szyszko, has been focusing on doing, rather than talking. He has introduced reforms that liberalize hunting and repealed laws protecting forests. As a result, Europe’s most precious primeval Białowieża forest, a UNESCO world heritage site, is no longer safe from logging, and an increasing number of trees growing on privately-owned land are reportedly being cut down simply to increase the value of the land, which is then sold for extra profit.

“A just society is measured by the way it treats its weakest,” said Holland in a press conference. Enyedi would agree that speaking for the weakest lies within film-makers’ responsibilities. Her On Body and Soul puts forward an even more convincing argument that our treatment of animals and the environment influences profoundly, though not always visibly, the way we treat each other.

Film and politics

This was the third year in a row that Polish films received Bears at Berlinale. Making successful films requires talent but it also needs political support and institutions.

“After the fall of communism, Polish cinema found itself in a limbo. We believed that the free market would give us freedom, but all it brought was the freedom to produce second-rate American movies. This could not accommodate our artistic aspirations,” said Holland. “In 2005, after a long political struggle, a cinematography bill was passed and the Polish Film Institute was created. New financing possibilities independent of the politicised state budget boosted a new generation of original and successful film-makers. It is the biggest success story I have seen in my lifetime.”

Ildikó Enyedi with the Golden Bear (Photo: © Berlinale)

But the recent resurgence of conservatism, nationalism, and authoritarianism in both Poland and Hungary is making film-makers there bite their nails in worry. “The country is becoming a more and more frighteningly absurd country, yet, so far, Hungarian film remains an island of refuge for artists and authors,” said Enyedi. “Knowing our new politicians’ love of destroying something that is alive — both in culture and in nature — Polish cinema is again under threat,” Holland told the press.

It seems that, after all, the first impression that burning political issues, like the refugee crisis, had given way at this year’s Berlinale to cinematic contemplation of old philosophical problems — body and soul, human and animal — was evidently wrong. Berlinale’s film selectors and juries stay true to keeping in touch politically. This, however, has also been interpreted as the festival’s chronic and somewhat morbid fascination with “problematic” countries.

Film poster promoting Spoor in Poland

Slaughterhouse as a social metaphor is certainly applicable, to a lesser or greater degree, to all of Europe and beyond. So much that the spread of nationalism and populism could, in part, be understood as a reaction to the increasingly rigid systematisation of life on the continent.

Both films, each in its own way, want to teach us a lesson about the inhuman nature of over-rationalisation inherent in technocracy, post-democracy, post-politics, etc. They also make the case that “the animal within” cannot be repressed and will not stay forgotten, that sooner or later it will remind us of its existence, no matter how hard one tries to hinder its expression.

If dreams gave voice to Marta’s and Endre’s unfulfilled desires by sending signals that circumvented the limits set by their rationality, then cinema as an industry of dreams can be seen sending, with these two films, its own warning about the current state of affairs. If we allow ourselves to inhumanly repress the animal within, then, to quote the famous opening of Terry Gilliam’s dystopian classic Twelve Monkeys, “once again the animals will rule the world”.

This piece was originally published on Katoikos.eu

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)