JOVANA GEORGIEVSKI

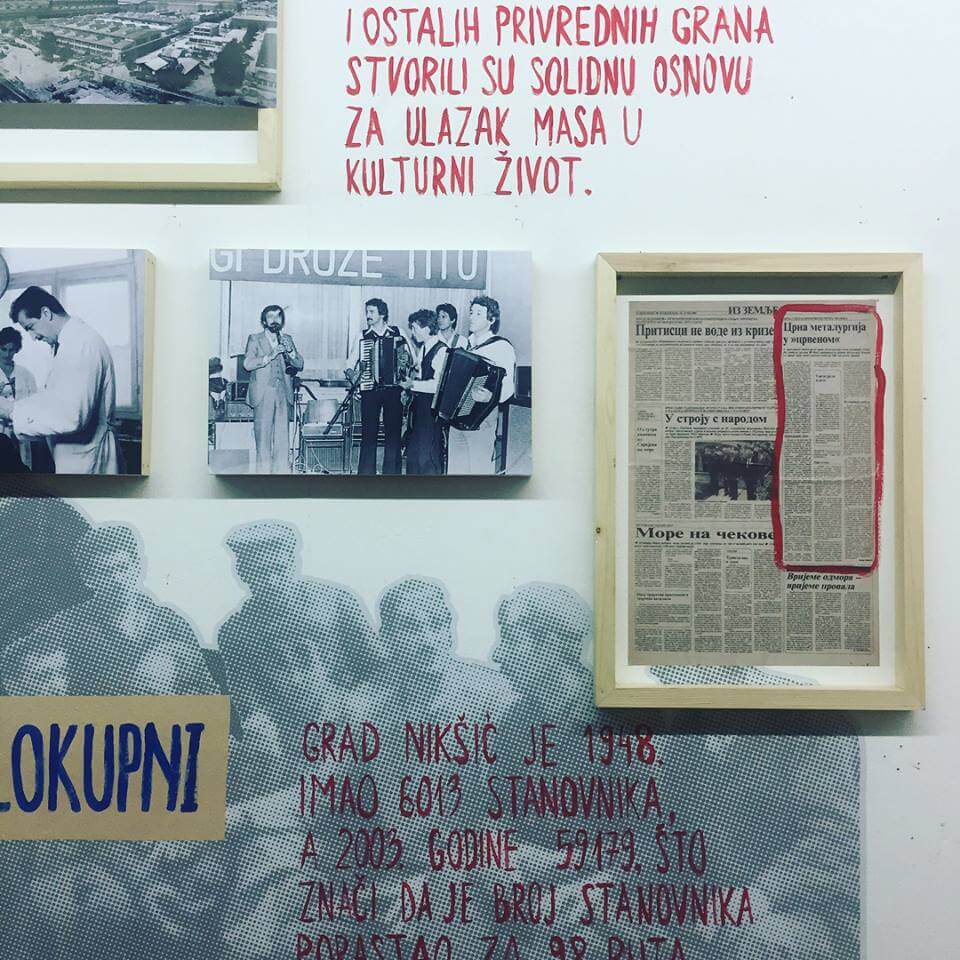

The opening of the “We Have Built Cities for You” exhibition on June 13 at the Cvijeta Zuzorić Art Pavilion in Belgrade, gathered artists and researchers from all the countries that once made up Yugoslavia.

The exhibition was organized as part of events commemorating 20 years of the Përtej (Beyond) exhibition in 1997, when artists from Kosovo exhibited in Belgrade. Twenty years later, the organizers are trying to look beyond other boundaries.

“We Have Built Cities For You” provides an exploration of the transition from industrial production under socialism to small capitalist economies formed after the breakup of Yugoslavia. What first strikes you on walking into the exhibition hall are the red letters written on the wall opposite the entrance:

Red is the blood that

boils in our bodies

Red is the bold that shreds

through the clouds

Red is the sky when it

laughs through the dawn

Red is our flag that

proudly flutters in the wind

These are the verses of the poem “Red” by Kosta Abrašević, written in 1894, that 80 years later, in April 1974, featured on the cover of the newspaper made and distributed by workers of the Astibo textile factory in Macedonia. The intention of the poem is clear: to raise the morale of the workers in the industry while meeting the workers’ need to fill their leisure-time.

The poem is only one of the aspects of life and work in the former Yugoslavia that the exhibition deals with. “We Have Built Cities For You” invites the visitor to reflect on the period of socialism and its contradictions through an exploration of economics, politics, workers’ self-management and leisure-time pursuits, the media, culture and art.

Visitors are presented with several case-studies about industrial zones all over Yugoslavia and in regard to various spheres of social activities, especially culture. Vida Knežević and Marko Mitrović, the curators of the exhibition, told K2.0 that they wanted, through wide-ranging research, to reflect on the overall complexity of the approach to dealing with Yugoslav socialism.

“The sphere of culture is particularly interesting because it is through culture that hegemonic liberal ideology coupled with nationalist policies are [currently being] reflected,” said Knežević.

The curators explained that working life in Yugoslavia was chosen as a theme of the exhibition because “the results of a decades-long process of transformation are most evident and measurable in the sphere of work.”

Knežević explained that the exhibition brings three different strands together: the striving of the working class to live better, the mission of the League of Communists to become ideologically stronger, and the logic of money and capital.

“These three currents had been contradicting each other, creating different situations in extensive periods of time that have influenced the lives of a lot of people. That is what we wanted to explore for this exhibition,” Knežević concludes.

Protesting against capitalism

The introduction of capitalism to the Yugoslav space did not unfold in a linear fashion and without resistance. The shift was accompanied by conflicts, both on a macro level, following the breakup of Yugoslavia, and on a micro level, in the factories and kombinats themselves, as a result of the resistance towards the imposed changes.

In the 1980s, strikes became a regular occurrence in cities throughout the country. From Trepca to TAM, from Labin to Zmaj, workers went on strike demanding better working and living conditions, protesting against austerity measures and the neoliberal restructuring of Yugoslavia, which was primarily supported and pushed forward by the political and economic leadership.

The shift from work in socialism to work in capitalism produced many contradictory political economic and cultural consequences. Within the small post-Yugoslav societies, as capitalism develops, it imposes a different set of rules than in socialism: workers working overtime, very often on weekends and holidays, without any financial compensation and under great pressure to achieve higher production quotas. Monthly income is often low and the attitude and treatment towards workers sometimes comes with elements of psychological violence.

For example, according to research conducted by the exhibition, Croatia is the leading country in Europe when measured by the presence of precarious types of work. In 2017, more than 8 percent of workers were employed in the domain of so-called precarious jobs.

The research also found that 90 percent of newly employed workers, as a rule, have been finding employment in precarious forms of work, part-time work and seasonal work, meaning no steady income, no pension insurance, no qualifying years of employment, no sick-leave.

One of the few workplaces in Croatia where workers still have their say is Petrokemija mineral fertiliser factory in Kutina. The factory’s recent history has been documented by photographer Bojan Mrđenović, who exhibited at “We Have Built Cities For You.”

“Petrokemija is still in state ownership, but privatisation is creeping in,” explained Mrđenović for K2.0. “The workers advocate against it. Despite the attempts of various local establishments to have the factory privatized, the concerted action of the united trade union workers’ front has prevented each attempt of that kind until today.”

The trade union at Petrokemija is a rare example of successfully promoting workers’ rights and preventing privatisation. Mrđenović’s exhibited work combines photos the photographer made himself while exploring Kutina’s industrial zone, as well as photos from the second half of the past century.

In this way, Mrđenović tried to contextualize the evolution of industrial production in Kutina since it was established in socialist Yugoslavia to the present day.

“Nowadays in Kutina, you have strong right-wing movement and the influence of nationalist narratives is omnipresent,” said Mrđenović. “Regardless of that narrative, no one can beat the fact that employability was never at such a high level like back in 1980s, in the golden times of Petrokemija,” he explained.

“Kutina is currently in the phase of economic and existential uncertainty due to pressures for privatisation and I am planning to document the course of the events further on,” said Mrđenović.

A political space for emancipation

Unlike Kutina, the Macedonian town of Štip is already fully immersed in capitalist working culture. Štip once had a strong and powerful textile industry which was the leading industrial branch in the town. With the sieve of privatisation, its leading companies Makedonka and Astibo were fragmented into hundreds of private manufactures, drastically changing labor relations.

At “We Have Built Cities For You,” Filip Jovanovski’s work, “Textile and Sorrow,” looks into Štip’s textile industry and the methods with which organisations of textile workers in Štip try to improve their labor and human rights.

For Jovanovski, Štip’s complex cultural past faced destruction during the “dark dictatorship period” (2006-2017). He feels that the strengthening of patriotic and strictly Orthodox conservative feelings were not on the side of the workers, but the resistance still seems to be there.

His work is presented in the form of newspaper edited together with workers and activists from the Loud Textile Worker Initiative. “We see the newspaper as a (political) space for emancipation and collective action for better human and workers’ rights,” stated the artist.

Another artist looking into workers’ rights is Croatian film director Srđan Kovačević, who spent 37 days in a Ljubljana with Delavska Svetovalnica (Workers’ Counselling Service), an NGO that assists migrant workers with administration and paperwork, making their life a little bit less complicated.

“What struck me most is the fact that between 10 and 30 people per day come to Delavska Svetovalnica’s office with stories about working in catastrophic conditions,” Kovačević told K2.0. “I was strongly affected by the injustice I witnessed.”

The director added that the only difference between him and the workers that came to ask for assistance was that, in most cases, they were working in physically worse conditions. What he has in common with them are the temporary contracts, late salaries and great pressure to produce.

“Seeing this made me want to engage politically and advocate against such practices, and not only present them from an artistic perspective,” said Kovačević.

Researcher Irena Pejić meanwhile, looked into the case of Sarajevo daily newspaper Oslobođenje (Liberation), a daily newspaper owned by the Socialist Association of the Working People of Bosnia and Herzegovina and a truly Yugoslav-oriented paper in the 1980s. Archive materials from the newspaper make up part of the exhibition.

“After the disintegration of Yugoslavia, Oslobođenje changed owners and faced constant struggles to keep the publication going,” explains Pejić in her text accompanying the work. The editorial staff today describes Oslobođenje as “Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian in equal measure, because it belongs to all the peoples and citizens of Bosnia and Herzegovina.”

Even though socialist Yugoslavia is often referred to as a country marked by party censorship and a lack of criticism, the case of Oslobođenje shows that the picture was not so black and white. During the times of deepening economic and social crisis, when everything may have been held in firm control of the Communist Party, Oslobođenje took the side of workers. “That is something that is not to be neglected,” Pejić states.

With these examples in mind, it seems that the intention behind the exhibition “We Have Built Cities For You” was not simply cultural. There is also a political idea, weaved into the work exhibited, implying that even though Yugoslav socialism and its emancipatory achievements cannot be transposed to the present time, they still contain certain political lessons — at least one on the necessity of struggle as an organized collective act aimed towards creating a new society of freedom, equality and solidarity.

***

This article was originally produced for and published by Kosovo 2.0. It has been re-published here with permission.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)