About three weeks ago The Guardian published the reportage by Lorenzo Tondo from Velika Kladuša, Bosnia and Herzegovina with a frightening title: ‘They didn’t give a damn’: first footage of Croatian police ‘brutality’. This wasn’t the first time that similar accusations were expressed in international media. Similar claims were published already in August, but activists from the field have been sharing many similar horrifying stories on social networks. Croatian police replied that “the police protect and control the state border of the Republic of Croatia” and will continue to monitor the state borders in order “to protect the border from illegal migrations”, saying nothing about the systemic violence that Croatian police is repeatedly performing on migrants. On the website Border Violence, since the beginning of 2017 about 200 cases of police violence at the borders between Serbia and Croatia, Serbia and Hungary, and Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia have been documented. Every day, new cases are being reported. We spoke with Sara Kekuš from Centre for Peace Studies in Zagreb about the current situation along Croatian borders.

Along the new migration route through south-eastern Europe, migrants are beaten, stranded, and neglected but it seems that the EU is looking the other way. Can you explain what has changed since 2015?

Solidarity and humanitarian response to the crisis have been replaced with efforts to keep the refugees outside of the EU or to return them to third countries.

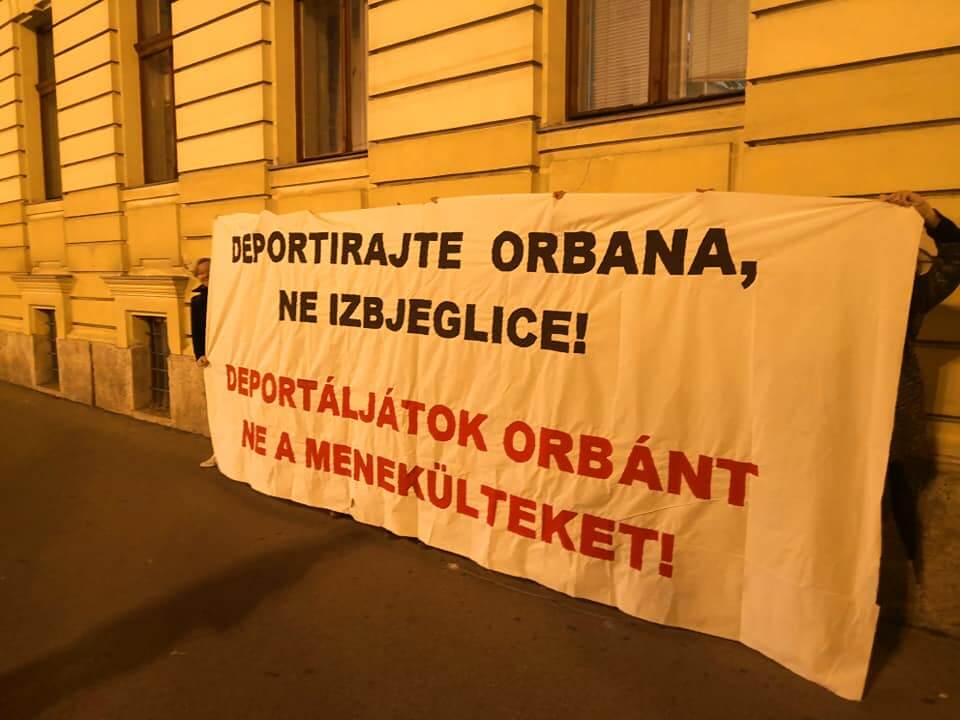

The EU migration politics have significantly changed since 2015. Instead of assuring safe and legal migration pathways and protection of human rights, the EU is externalising migration and focusing on protection of its borders. Solidarity and humanitarian response to the crisis have been replaced with efforts to keep the refugees outside of the EU or to return them to third countries while compromising the principle of non-refoulement. The change is visible through agreements with countries such as Turkey, Afghanistan and Libya, as well as with indications of the extension of the definition of a safe country to Georgia, Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco. The member states are using asylum and migration policies selectively, i.e. disabling safe passages, exempting from the agreed quota system and derogating the Common European Asylum System (CEAS), while encouraging far-right and anti-migration propaganda, promptly returning people by Dublin III regulation and criminalising acts which were previously seen as acts of solidarity and humanitarianism.

The so-called Balkan Route has changed since the beginning of 2018. The pressure is now on one of the poorest country in Europe, Bosnia and Herzegovina. What caused these shifts in the route?

People were stuck in Serbia ever since the corridor through the Balkan Route closed (spring 2016). With inadequate living conditions and failed attempts to reach Croatia due to the policy of pushbacks and violence of the Croatian authorities, people started seeking new routes to reach Europe, and so the route moved towards the borders of Bosnia and Herzegovina with Croatia. It was a logical and expected turn of events, as migrations cannot be stopped with the closure of borders. As long as people are exposed to any form of violence, as long as they are searching for peace, security and a stable life, they will migrate.

The EU and Croatia are leaving Bosnia and Herzegovina alone in that game, making a hot-spot out of it, instead of deciding on legal pathways for people to reach other European countries. No country, big or small, can provide the answer to migration alone. Instead of focusing on fortification of Schengen borders, the EU should focus on providing support to Bosnia and Herzegovina and on distributing the responsibility by receiving refugees in their own countries. What is happening now, with the closure of borders, wires between the member states, and strict border controls, is contrary to what Europe says it stands for. Freedom of movement seems to be reserved for goods, but not for people.

No country, big or small, can provide the answer to migration alone.

There, migrants are forced to live in horrifying conditions, but the support of the locals is strong. That means that citizens are often taking responsibilities of the state. We have seen similar actions in Croatia. Since you are working for the Centre for Peace Studies and collaborating with different initiatives, can you elaborate how this works in practice?

The conditions are not adequate to fulfil the basic human needs. However, even if they were, there is much more effort and change that needs to be done in order to ensure a functioning asylum system and effective integration system that actually enables people to feel included in the society and enables them to work and have a decent life.

The Bosnian authorities lack will to improve the situation, and the EU is not doing anything to help. So again, we have local people who, alongside local and foreign NGOs, are trying to fill the gaps, provide with the essentials and restore dignity.

In tackling the issue of the current situation on our borders and access to asylum, we try to combine advocacy and fieldwork. We established good connections with some of the NGOs who are actively working in BH and gathering testimonies of people who have been pushed back. We try to go regularly to BH to track the situation, see the changes and see in which way we can help best, as we are not focused on humanitarian aid, or able to provide constant support on the field. We try to report about the situation on the national and European scale, through various instances of media and institutions, warning about dangerous policies and practices and tackling the fake news and imaginary threat that politicians are making of refugees seeking safety on our borders.

We have local people who, alongside local and foreign NGOs, are trying to fill the gaps, provide with the essentials and restore dignity.

Croatia and Slovenia, the only member states in the region, are seen as a big step towards more desirable states in the EU. But their borders are militarising every day. What has happened along Croatian borders in the last few months?

The situation on the Croatian borders did not significantly change within the last few months. We have been reporting about pushbacks and violence for more than two years now. What did change, however, is Croatia’s fixation on entering the Schengen area and making that a priority at the expense of human rights. The anti-migration and national security-focused politics further encourage the idea of militarisation of borders, and encourage the myth of migrants as a threat, instead of treating them as people in desperate need of protection and safety, who they actually are. We should not forget that this is all reported by organisations such as UNHCR, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, No name kitchen, Red Cross, Welcome Initiative, Are You Syrious and Centre for Peace Studies, as well as The Ombudswoman of the Republic of Croatia, and Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights. It seems that the whole of Europe knows what is going on at the borders, that people are getting beaten, and do not have access to asylum system, but Europe does not only close its eyes, Croatia even gets tapped on the shoulders for its actions, that is what Angela Merkel did to Andrej Plenković, Croatian Prime Minister coming from the same EU political family.

On the one hand we have locals helping in their own capacities (and beyond that) and on the other there are states using violence as their main policy. Activists helping migrants are also attacked. How is this related with the rise of far-right not only in the region, but also in the EU?

There are clear pressures towards NGOs through criminalisation of volunteers providing assistance and disabling some forms of their work.

We can observe the changes in Croatia within the broader context of criminalisation of solidarity in Europe. In some EU states, the criminalisation of solidarity advanced significantly. However, what we see here surpasses the criminalisation of solidarity. There are clear pressures towards NGOs through criminalisation of volunteers providing assistance and disabling some forms of their work (i.e. kicking them out of the reception centres). But what is worrying is that it is a broader attempt to shrink the civil society. Especially when combined with lack of effective investigations and expansion of arbitrary police action, followed by dependent and hysteria-prone media. And we can ask ourselves who is the next imaginary threat? Because it just begins with migrants as the currently weakest members of the society. Everyone else can be next.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)