Hafed Bouassida was one of the so-called Third World students who came to study in the countries of the former Eastern Bloc. These study visits were conceived as international support for countries in Asia and Africa. This support had its ideological roots in socialist internationalism and solidarity with countries fighting with the legacies of colonialism. Many students in the arts decided to dedicate themselves to film, which seemed to be an effective educational and political tool. Film schools in Moscow, Łódż and Prague contributed significantly to the development of African and Asian cinema.

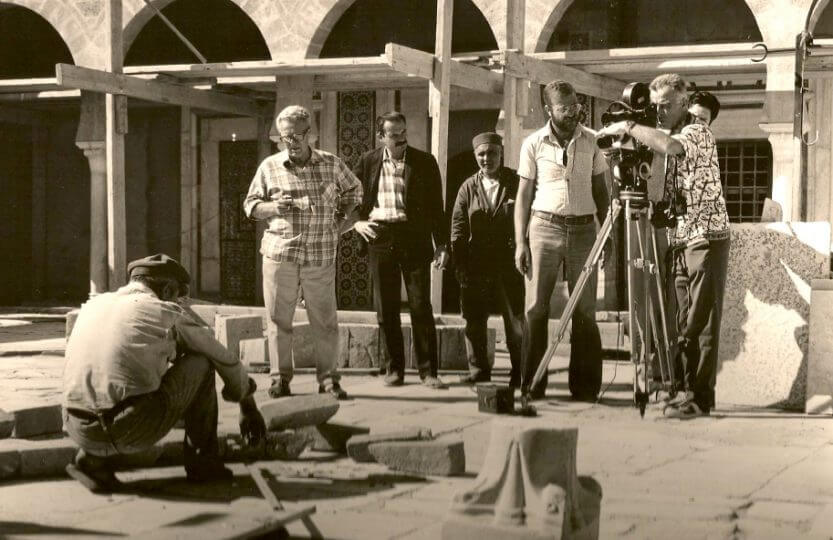

Hafed Bouassida studied at Prague FAMU film school between 1969 and 1974. Working with the Czech documentary film maker and theorist Alan František Šulc, he made several remarkable documentaries about North Africa.

Tereza Stejskalová: When did you come to Czechoslovakia?

Hafed Bouassida: I came in late fall 1967, despite the opposition of the Tunisian government, which offered me a scholarship to the Paris Film School, IDHEC. At first, I stayed in Dobruška, a little town where I took an intensive Czech language class with other students for about six or seven months. We studied Czech for the whole day and since there was nothing in that small town besides a tired old movie theatre, we would often join the locals in the pub and pretty much got drunk with them. That’s where I met the Lebanese filmmaker André Gédéon Maroun and others who later became friends and colleagues.

Hafed (Abdelhafidh) Bouassida

is a Tunisian film director, screenwriter and producer. In collaboration with the Czech filmmaker and film theoretician Alan František Šulc, he produced a number of documentary films about Tunisia including Berber Rhapsody (1980), which won the UNESCO prize at the Pan-African Short Film Festival in Paris, 1981. He later produced several documentaries about Africa, and the Middle and Far East. He currently chairs the Cinema department at Minneapolis College, in Minnesota (USA).How did you experience the events of 1968? They took place shortly after your arrival.

I was out in the streets the whole time. Everybody was writing texts or pamphlets, drawing cartoons, etc. So I wrote this short story –A Dialogue in One Voice. It was published in a semi-clandestine literary journal called Divoké Víno (Wild Wine) in 1969. You can still find it on the Internet.

What is it about?

It’s a short story about a pretty messed-up young man who works as a tour guide in Tunisia. You know, many tourists came and still come to Tunisia for sun, sand and sex. And this guy simply took advantage of it, just like many other guides. It was critical of mass tourism in Tunisia. Obviously, it did not directly refer to the events in Czechoslovakia. However, since I was describing a society in deep crisis, it was interpreted as an allegory of what was happening in Czechoslovakia at the time. I got into trouble because of it. The authorities questioned my real objectives with the piece. I acted innocent and said that it was simply about me and how socially messed up Tunisia was…

Can you describe to what extent you were involved in the Prague Spring movement?

During the 1968/1969 academic year, I started a preparatory year at FAMU during which I was taking general education classes and shooting my entrance film for the film school. There was already turmoil in the spring. I took classes with people such as Milan Kundera, Elmar Klos, Frank Daniel and A.M. Brousil, the dean of FAMU at that time. The atmosphere was very exciting. Often, regular classes could not be held. There were endless and lively discussions inside and outside of school. At one point, the students didn’t want to go home at night. The teachers stayed with them for many nights in a row at FAMU. Technically, we were living in the FAMU building, eating down at the Slavia Café, and protesting…

For me, it was a coming of age period that I cherished. I was right in the middle of a revolution that I couldn’t have imagined. Everybody felt that something extraordinary was going on, bigger than anything we could fathom. Every night we went out to watch this or that film, which either was, or ended up being prohibited after the invasion. Jan Němec, I thought, best expressed the absolute absurdity of the social relations in Czechoslovak society at the time. One summer night, August 20th to be exact, I remember watching his film A Report on the Party and the Guests. It ended at 10 o’clock. I was overwhelmed. I thought to myself – this is so absurd and tragic that it could never happen in real life. But it was almost a sort of premonition. The next day, at five in the morning, there was a tank in front of the FAMU dorm. Reality and fiction merged into one.

What did you do then?

Not much at night as there was a curfew. But during the day I went out like everyone else to see and add more new “graffiti” and poetry and other slogans on the streets criticizing the Russian invasion. And again at night, the Russian Army would take down the pamphlets and repaint the walls. And again, the following day even more graffiti appeared on the walls. It was an ongoing war between the people and the occupiers…

I remember that my documentary film professor A.F. Šulc and other teachers like František Daniel, encouraged us to take cameras, go out and film whatever was going on despite the fact that school was out for the summer. This was a once in a lifetime opportunity, especially on and after August 21st. We were part of a historical moment and felt the urgent need to present it to the rest of the world- to document it for posterity if nothing else. After all, filmmaking is about feeling the urge to document on screen pivotal events that take place in front of you. The idea was that maybe someone would find a way to smuggle the footage out of the country in case things got worse. So a whole bunch of students took to the streets to shoot whatever they could on cheap and noisy 16mm cameras, without sound, or on simple snapshot cameras.

Were there many foreign students?

I might have been one of the few foreign students who were actually involved in this endeavor. Others could not participate as they were there on scholarships from their governments. Obviously, they needed to be careful. Otherwise they could be sent back home. That was not my case. I was kind of free.

What do you mean? Did you fund your studies on your own?

No, I wasn’t that rich! I actually received a scholarship from the Czechoslovak government. Every year, as part of a political promotion programme, the Czechoslovak government would select a few people from all over the world and offer them scholarships to study in Prague or Bratislava-generally through the ill-fated November 17th University. The obvious goal was to recruit them as sympathizers of the system and the country. That was my case!

For me, it was a coming of age period that I cherished. I was right in the middle of a revolution that I couldn’t have imagined. Everybody felt that something extraordinary was going on, bigger than anything we could fathom.

After two years, however, I was told that my scholarship was over. I don’t know if my insignificant participation in the 1968 events played any part in this. This was really bad because I still wasn’t rich and couldn’t fund my studies on my own. But as luck would have it, the Tunisian TV president at the time came to Prague for an official visit, and I managed to get up enough courage to tell him about my situation and somehow dare him to not be the usual bureaucrat and for once to put his money where his mouth was. He took up the challenge after a few Plzen beers he promised to do something about it. And lo and behold, he actually delivered: the Tunisian government offered me a tiny scholarship for another four years. That was good enough to help me continue with my studies while doing odd jobs in the field, such as working as assistant director or production assistant for Czech Television and on some local productions.

Did you experience a language barrier? Was learning Czech an obstacle?

Language barrier? No, at least not for me! I knew multiple languages when I came to Prague. It took me a year or so to really learn Czech and I ended being pretty good at it. As a matter of fact, after a few years, people could barely notice any accent when I spoke.

I assume you chose FAMU because it was supposed to be a good film school. Was it also important for you that you were going to a communist country? Did you care at all?

I grew up between Tunisia and France. My political views at the time were definitely leaning to the left. After all, the world then was slowly heading into the late sixties, a period that was tumultuous pretty much everywhere. Actually, I suspect that the Tunisian government didn’t offer me a scholarship because I was too left-leaning for my own sake and theirs. But I might be wrong, because that very same year I came to Prague, not one, but four other Tunisian students came to FAMU through official governmental agreements between Tunisia and Czechoslovakia. And they didn’t even have to go through the formal interview or acceptance process.

I was in a completely different situation. In my case, I knew exactly where I was, why I was there, and what I wanted to do. I came on my own, after a bitter fight with my government who wanted me to go to Paris, and only after spending an entire preparatory year shooting very specific films required by FAMU was I accepted into the program.

By the way, two years before 1967, Prague was not where I wanted to study. My first choice was the film school in Łódź, Poland, which was famous at the time. If you wanted to study great filmmaking by great film teachers, you went to Łódź.

So why didn’t you go to Łódź?

I was at the Venice film festival around 1963-64 where I met the Polish director Andrzej Munk whom I deeply respected. We started to talk. I was a young kid, trying to get into the most famous film school at the time. And after a few vodkas at the bar, he simply said: “Do you really want to learn how to make films? If I were you, I wouldn’t go to Łódź, now. It’s not such a good school anymore. Go to Prague instead. That’s where things are happening.”

I knew about the New Czechoslovak Wave, but I didn’t know much about the Prague film school; so I researched it. I learned about all these fascinating Czechoslovak films but I couldn’t see them, certainly not in Tunisia.

In one of my visits to France I saw Loves of a Blonde by Miloš Forman, Menzel’s Closely Watched Trains, and many more. They were mesmerizing! I also saw The Shop on Main Street, which ended up winning the Oscar for best foreign film. Who would have imagined that one of its directors, Elmar Klos, would end up being my teacher?

All that made me more resolute to join FAMU rather than Łódź, and definitely not Paris, which according to Andzej Munk, was also losing its fame, while Prague was on an upward, dynamic and exciting trajectory.

That very year, 1967, there was a nascent film festival in Tunisia for amateur filmmakers. I made a short film and entered it in the festival. Among the very few foreign participants, there was an advertising producer from Prague. We quickly bonded. I told him about my plans to go to Prague and he promised to talk to the 17th November University. And indeed he told them about me and about my plans.

One day I was invited to an interview at the Czech Embassy in Tunisia. After seven hundred questions and some waiting, I was finally accepted to study in Prague and granted a Czechoslovak scholarship. I could have gone to France and it would have been much easier politically and less risky. I even had relatives there. However, I really wanted to try and live in a politically left-leaning country. I wanted to see the world from a fundamentally different perspective.

How were your leftist opinions affected by the events in Prague?

Man, it affected me for life. In the U.S. they still call me a socialist and sometimes even a communist for my bold egalitarian ideas and my belief that excessive wealth always comes with a price for the rest of the society. I am not a communist but I believe that socialism is an important component of life. I live in the U.S. where capitalism is, unfortunately, out of control; I don’t believe that a society can indefinitely sustain such a rabid, capitalist way of life such as the one currently existing in the US. I don’t think you can ostracize entire classes of hard-working people. I don’t think you can survive with such incredible income inequality.

My experience in Prague, however, also affected me profoundly in a different way. When I was in Czechoslovakia I was not the typical, brainwashed student they expected me to be when they gave me the scholarship… I was one of those who strove to change the system. I talked to regular people, I lived with them and quickly understood their deeper yearnings. I quickly became part of the political, artistic and cultural fabric of society. I still thought that Marxism was theoretically an attractive and exciting philosophical concept, but as I was confronted with people’s daily needs, I realized that something was not working properly and that ideas and reality did not necessarily match. Being a left-leaning intellectual in Paris was not exactly the same as living the communist reality of Prague at the time.

Ultimately, I came to believe that there should be a different approach to rules and rights in society. Regular people should have the right to privacy, personal freedom, and participation in political life. So I’m not a dogmatic, die-hard left-wing intellectual who lives and dies by Marxist principles. I believe, however, there should be some sort of socialist necessity, such as in democracies like France or the Scandinavian countries. I don’t think that extremes work.

What was FAMU like after 68?

Big changes! Teachers like Milan Kundera and František Daniel fled the country. Others simply retired, and a few, like Elmar Klos, were eventually fired. Those who for whatever reason stayed, were ultimately muzzled…Instead of Elmar Klos, we ended up with Jiří Sequens. He was a likeable man who produced some attractive action movies, a good technician who knew the craft. He was, however, not that creative a teacher, not very inspiring or uplifting, not open to newer or uncommon ideas. We continued to meet with our original teacher, Elmar Klos, unofficially of course, and despite all odds.

Who were your classmates?

There were seven of us at the beginning. But by the end of the first academic year, there were only four – Husein Moussa from Syria, Lubomir Mauer from Norway, Vladimir Blazek from Prague and me…

So it was a class of foreigners.

Well, you certainly could call it that way with 75% of foreigners… But it didn’t start out like that and I’m not sure that anyone then felt uncomfortable about how it turned out to be. I don’t remember at the time any arguments, or even noticeable xenophobia…

Can you describe how your studies at FAMU influenced your filmmaking?

For me, coming to Prague was not just about learning how to produce and direct films. It was about acquiring a worldview and a new aesthetic and creative vision. I wanted to make films, I wanted to learn the craft, I wanted to learn how to express my ideas and views à la “Czech New Wave.” However, I could have gone to Paris for that, or Brussels, which wasn’t a bad school at that time.

My experience in Prague affected me profoundly. When I was in Czechoslovakia I was not the typical, brainwashed student they expected me to be when they gave me the scholarship… I was one of those who strove to change the system.

But what was important to me was to gain a new perspective on life, a new point of view, and a new approach to creative thinking. I wanted to approach characters and events and the intricacies of what happens in a story from the way I discovered in the Czechoslovak films, fresh, unhinged, free and somewhat irreverent and controversial, not altered by the fear of getting into trouble if shared with viewers. And I did. It was a life-altering experience.

I was lucky to meet someone like Elmar Klos and have him as a teacher. Those seven years in Prague completely transformed me. Prague gave me the ability to make films deeply entrenched in the societal fabric and interactions, and to share uncommon and not necessarily comforting perspectives with the viewer. Which later on did not please the Tunisian government and I paid for it.

However, Prague also gave me a keen sense and a deeper understanding of how society should function, and what a citizen can do to be fully part of it. It also affected my personal life to this day, as half of what I say or think on a daily basis is in Czech and most films I produce end up reflecting themes and stories prevalent in the Czech psyche.

How did your collaboration with A. F. Šulc, the documentary filmmaker and theoretician, come about?

I only had him for one class on documentary filmmaking. We started to talk and quickly became friends mostly because he had visited Tunisia and even produced a few documentaries about aspects of the country. We literally bonded.

Later on, he invited me to help out at the Karlovy Vary film festival. An official delegation came for the screening of a Tunisian film at the festival. Not much happened right then, but when I went back to Tunisia, I talked to the president of SATPEC, the national production company, and somehow persuaded him to consider the idea of collaboration.

How did the collaboration work out?

Surprisingly well for a younger director collaborating with a mature educator and filmmaker. We complemented each other. My unbridled passion and urge to produce controversial and creatively immature films was tempered by his thoughtful and serene experience. He hammered into my head the way to reach my goals as a director, how to collaborate and how to express my ideas in a clear and effective way for the actors and the crew. We ended up with four or five collaborations: Report on Medina (1979), Carthage the Eternal (1979), Berber Rhapsody (1980) and The Miracle of Water (1980).

What about The Ballad of Mamlouk (1981), your first feature film? It was also a Tunisian and Czechoslovak co-production…

It was a very sorry experience. There were too many compromises all along the way, mostly by me. Just like the short films, it started as a co-production between SATPEC and Krátký film. It was supposed to be a follow-up to the other four films I directed with Šulc.

The film suffered from every possible problem, starting with my definite inexperience facing such a huge task, then a lack of finances, insufficient infrastructure, poor choice of actors who didn’t even understand each other’s language, a main character who had to act there in order to pay off a debt with the Tunisian producer, you name it! I realized, just like Rosemary, that I had created a baby monster that I couldn’t control. From what I know, I don’t think that the film made any money in distribution…

Do you follow what’s going on in Tunisian filmmaking?

I left Tunisia many moons ago. Since 1988-1989, I haven’t been very active there. I was hired by a company in Munich that produced films for different German TV channels to produce and direct a whole series of films about the Middle East, Africa, and the Far East. Then I went to the U.S., which was one of the very few places I hadn’t worked. I came to Minneapolis where, while looking for production jobs, I started teaching Film and Video at a local College. Two years later I created the screenwriting program and the initial modest program morphed into an entire Cinema department. I currently chair both the department and the Screenwriting program.

I’m a little out of touch with what’s going on in Tunisia. I really need to go there again. It’s fascinating right now, as Tunisia has transformed into most likely the only democratic country that is left in the entire Arab world. I like the resonance with the Prague Spring, but it might just turn out like what happened in Prague, since dark extremist forces are still trying to sabotage the new march toward freedom and democracy. I hope they won’t succeed!

***

This article was originally published on A2larm.cz

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)