This Friday and Saturday, Czechs will head to the polls to decide how to face the winds of change. The country has been at the center of both the Refugee Crisis and the political fight inside the EU over a shared immigrant resettlement policy. Polling suggests that the right will win this week’s parliamentary election which could further tilt the balance towards right-wing populism in the region and Europe as a whole. So who’s running and what do they believe?

ČSSD – the Czech Social Democratic Party

ČSSD – the Czech Social Democratic Party

By Pavel Šplíchal

Despite the current ČSSD-led government being perceived by the public as more or less successful, in this election, a gain of parliamentary seats awaits only its coalition partner – the movement ANO of billionaire Andrej Babiš.

There are several causes of the party’s almost certain failure in this election, even though the huge drop in the polls seems almost unfair after four relatively successful years. The government pushed through an increase in the minimum wage by almost fifty percent and the economy has come out of a recession following two right-wing governments. And yet, ČSSD cannot capture the interest of voters; in part because it remains entrenched in parallel structures that emerged from regional organizations and clientelistic networks connected to them, something that Andrej Babiš likes to call attention to, in part because the party line vacillates and isn’t capable of providing the voters with a clear explanation of what the party actually wants to achieve and reasons to vote for it.

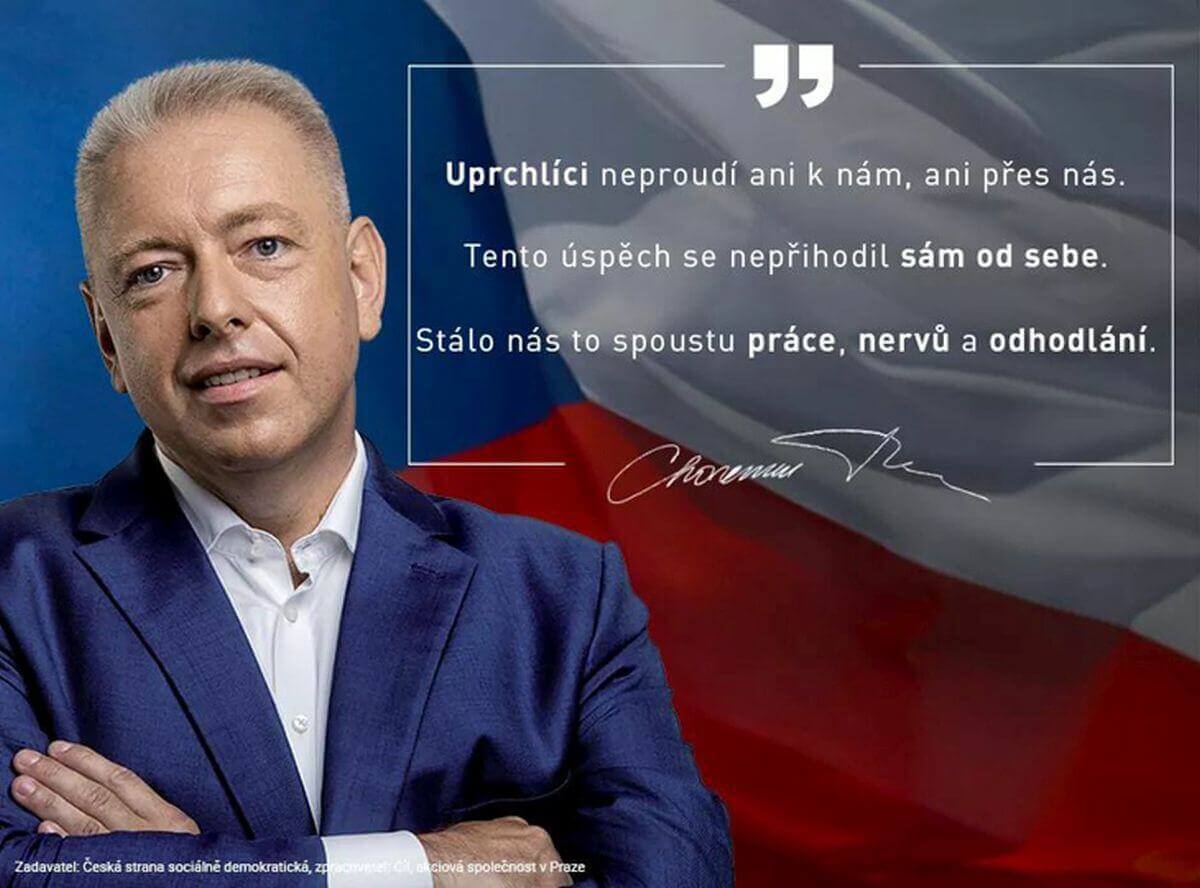

A last-minute switch occurred of wishy-washy premier Bohuslav Sobotka as party leader in the election for Lubomír Zaorálek, who strives to emulate Jeremy Corbyn, but this move hasn’t won much favor from the voters. On top of that, a part of ČSSD, including its acting leader and Minister of the Interior, Milan Chovanec (as if there weren’t enough leaders), is adopting far-right rhetoric regarding the negative stance towards refugees and the fight for the right to bear arms. While ČSSD has thus rid itself of its reputation as do-gooders, it has also alienated liberal-minded voters. There is nothing significant ČSSD can do about the course of the East European type of capitalism, characterized by ownership abroad, precarious work, and the experience of shock doctrine in the nineties. However, as the only relevant political force, it has always sided with the less fortunate. Every post-election coalition without ČSSD would thus be worse than one where the Social Democrats actively figure.

ANO – Action of Dissatisfied Citizens

ANO – Action of Dissatisfied Citizens

Andrej Babiš and his ANO movement have managed to turn the Czech political scene upside down. Babiš entered politics as a representative of entrepreneurial populism – he belongs to a similar category as Silvio Berlusconi in Italy. Like Berlusconi, Babiš took advantage of the crisis and disintegration of traditional right-wing parties and offered voters a business plan rather than a political platform, one that consists of managing the country as a prospering, debtless company. Babiš wants to manage the state like a business and defines himself sharply in opposition to the other parties, be they right- or left-wing, labeling them as corrupt and incompetent. He also profits from his ethos of a rich and successful entrepreneur – the owner of the agricultural corporation Agrofert. ANO stands out thanks to its exceptionally efficient PR and the way it deftly shrouds a right-wing political agenda with its apolitical, technocratic lingo.

Since 2013, ANO has been part of the ruling coalition along with the Social Democrats, it has however shifted even further right since then and has gradually begun to resemble the positions of the conservative governments in Poland and Hungary. Babiš has spoken out strongly against taking in refugees, he is unstinting in his criticism of the European Union, and his platform prioritizes the “protection of national identity” and an increase in the military and intelligence services budgets. The polls clearly show that ANO is set to win a landslide victory in the upcoming parliamentary election. If Babiš manages to form a government, a push for greater centralization of power is to be expected. Nevertheless, he probably will preserve the basic means of social security – Babiš would otherwise risk turning against himself those voters who had defected to ANO in the past years as dissatisfied supporters of the Czech Social Democrats. The extent of Babiš’s authoritarianism will then depend on whether, and with whom, he will form a government. One option is to restore the coalition with Social Democrats, but it is still impossible to rule out worse scenarios, like the potential alliance with the proto-fascist SPD Party of Tomio Okamura.

Jaroslav Fiala

KSČM – the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia

KSČM – the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia

Unlike the majority of its regionally equivalent parties, the Czech Communists, who governed the country from 1948 to 1989, had no desire or need to rename or reform themselves, let alone act as a modern left-wing party. Although they split from the KSČ – the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia – in the early 90s, the extensive personnel and ideological interconnectedness leaves no doubt that this is an anachronistic party. All the parties, including the left-wing ČSSD, have long kept the communists at arm’s length (although regional cooperation has been getting more and more acceptable in recent years), and so KSČM has always operated on the fringes of the political spectrum with little decision-making power. Regardless, the party has maintained a stable support of around 15% of the electorate since the nineties. Early on during the transformation, a heated debate took place over a possible ban on the Communist Party; however, the notion of pluralistic political representation won out. In retrospect, it seems to have been the right thing to do. KSČM is not only a party of dwindling, nostalgia-ridden supporters, it has also been, since its formation, an effective siphon of protest and fringe votes. If it had been banned, who knows what kind of extremists would have popped up in the 90s and 00s.

Today of course the party faces strong competition in attracting protest votes in the form of far-right nationalists, from whom it does not differ much. A strong pro-social and redistribution-focused platform is no surprise for a self-declared Communist Party. However, regarding the rest of their standpoints, the name seems to miss the mark. Strong nationalism, anti-European views, objecting to NATO, the vehement rejection of refugees, even social conservatism – this mixture of defending both Czech values and the authoritarian practices of the previous regime would seem to suggest the name “National Socialists” as more befitting for this party.

Veronika Pehe

ODS – the Civic Democratic Party

ODS – the Civic Democratic Party

ODS is the right-wing offspring of the Velvet Revolution-era Civic Forum. The founding father, Václav Klaus Sr., has impacted the nature of the transformation in the Czech Republic. His standpoint can be illustrated by this statement: “I’ve been incessantly advised by Havlists that after decades of communism, what our country needs above all is morals. I, in turn, would tell them that what we need above all is a free market. While you can impose a market, you cannot do so with morals.” He not only massively influenced the attitudes of his party, but that of a considerable part of the Czech right as well. He does not register any destruction of our planet, he meticulously distinguishes between foods, clothes, and sports as left- or right-wing, and he regards journalists as the arch-nemeses of humankind. This person became the president and was succeeded by Miloš Zeman, who has more in common with him than just their shared attitude to journalists.

His party achieved its all-time high during the leadership of Mirek Topolánek in 2006 when it won 35.8% of votes. After the government led by Topolánek fell, the party has gone steadily downhill from there. Catholic nice guy Petr Nečas, a father of four, became the leader and managed to secure 20.22% of the electorate vote. However, he rounded off his political career with a scandal in which his employee and lover, Jana Nagyová, had Nečas’s wife monitored by the military intelligence services. In the following election, ODS reached a decent 7.72% result.

The present leader is another forgettable nice guy type, the former rector of Masaryk University, Petr Fiala. He is not expected to last long in this position. There are different, bolder characters within the party. Jana Černochová, the leader of the party in Prague, doesn’t like immigrants, but enjoys shooting guns and shooting pictures of herself with guns. However, the greatest hope for the future is represented by the founding father’s son, Václav Klaus Jr., who uses his blog to disseminate his opinions on the dangers of the European Union, dangerous immigrants, and dangerous inclusion. ODS has something around ten percent at the moment. If it were to be part of the government, it would be in charge of the ministry of education. And that would not only be the end of inclusion, but apparently of the education system as such.

Saša Uhlová

KDU–ČSL – The Christian and Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People’s Party

KDU–ČSL – The Christian and Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People’s Party

“We need Czech children, otherwise we’ll have to bring in people from abroad,” Pavel Bělobrádek, the supposedly liberal leader of the Christian Democrats, has proclaimed on a press conference of the party, and is quick to propose a whole package of measures on how to secure those Czech children for Czech labor. The People’s Party in this country have always bet on the family. A man, a woman, at least two children. In short, a decent sort of foundation for the state that, as Bělobrádek notes, is the focus of their interest. This party, which has strived to cultivate an image of God-fearing lambs for itself over the years, is at its core primarily a synonym of deservedness. Those who don’t work shouldn’t eat or have a place to live, maybe shouldn’t even be alive, one might say after reading through their platform policies. Solidarity and compassion for thy neighbor are no longer in vogue, so why should the populars, of all people, concern themselves with such, just because the current pope is somehow somewhat of a Neo-Marxist and do-gooder. Every age needs its heroes who aren’t afraid to speak the truth. And the main representatives of KDU (a party that does not have a single woman on its board), Pavel Bělobrádek or Jan Bartošek, are such heroes. When they see a single mother, they’re not afraid to advise her to find a man (heaven forbid a woman!) so they could face poverty in God’s love together. When they encounter a homeless person, they don’t hesitate to explain that housing is “a merit-based and costly issue.” They’re definitely right, at least regarding the second matter. This however isn’t reflected in their politics.

In the Czech Republic, KDU – ČSL has the reputation of an opportunistic party whose only goal is to be part of the government. Even their platform this year corresponds to this. It comprises an agenda of the old world, when “men were men” and “women were women” (thus spending their days in the kitchen and popping out children), when toxic ‘homosexualism’ and gender ideologies didn’t exist, people attended church more often and devoted their daily life above all to modest preparations for kingdom come. It’s a platform for the family, work, God, and the state. And as such it has the support of about six percent, according to pre-election polls. One might say that’s more than enough.

Apolena Rychlíková

SPD – Freedom and Direct Democracy – Tomio Okamura

SPD – Freedom and Direct Democracy – Tomio Okamura

SPD is the third attempt of Tomio Okamura, a tycoon in stuffed animals packages, to seize a shred of political power. Following a botched attempt to run for president, marked by a surplus of falsified signatures, and a political party that promised everything left and right whose funds had been embezzled spectacularly, Okamura decided to play it safe and launched an election campaign based a topic close to the heart of every decent, racially pure Czech. He aims to make it to the parliament with his platform supporting racism, xenophobia, and discrimination. The fact that a Czech-Japanese man is appealing to his electorate with slogans like “Czech lands to the Czechs” apparently doesn’t bother his supporters.

The SPD platform offers a tragicomic mishmash of general hogwash (Remove politicians from office! An end to tax hikes! Cheaper butter!), measures that will make your skin crawl (We’ll restrict religious freedom! We’ll restrict the distribution of benefits to those who don’t lead orderly lives, and only we know what makes life orderly!), and slogans the perpetrators of the texts apparently didn’t think all the way through (No money for immigrants and parasites!). All this is backed by a very consistent anti-European party line and a systematic denigration of “Brussels” and “nonprofit organizations.” Tomio doesn’t bother to cover up the blind love of every patriot for their country: in his case, that country is Russia, the subject of many an enlightening speech delivered at the parliament. Which one might think could prompt some of his voters to think twice, if they weren’t all looking out for those refugees.

Michal Chmela

TOP 09 – Tradition, Responsibility, Prosperity

TOP 09 – Tradition, Responsibility, Prosperity

TOP 09 is a right-wing conservative party which has garnered favor among urban liberals. It began as a project of one of the most distinct figures of post-Velvet Revolution politics, Miroslav Kalousek, who used to serve as an MP and the leader of the Christian Democrats. In the nineties, during his stint at the Ministry of Defense, Kalousek had been in league with armaments companies. providing them with advantageous deals. In the past, the leader of the party was entangled in many a corruption scandal, but he has always managed to skillfully extract himself from any allegations. Kalousek came up with TOP 09 prior to the parliamentary election in 2009 with the intention of creating a suitable coalition partner for ODS. In the newly created government, Miroslav Kalousek became the Finance Minister, pushing for draconian austerity policies and using rhetoric to successfully stir up class hatred aimed at the poor. He also became the emissary of the gambling industry – thanks to the exceptional benevolence of the Ministry of Finance, the number of slot machines per capita in the Czech Republic became the highest in the world. He also helped push through a property settlement with the churches that was very unfavorable for the state.

TOP 09 is vying for the young by comparing first-time voting with first-time sex. Unfortunately with the help of some particularly awkward rapping

Miroslav Kalousek’s activities led to the intensification of the negative social impact of the economic crisis. The party has managed to maintain its cool image among its liberal voters chiefly due to the figure of the aging aristocrat, Karel Schwarzenberg, who’s maintained an aura of upper class dissident and who comes across among other politicians as exotic due to his characteristic bowtie and more. After TOP 09 entered the opposition, it lost a significant part of its voters whom the party strives to retain mainly via its pro-European rhetoric.

Václav Drozd

The Green Party

The Green Party

An increase in minimum wage, higher salaries for teachers and medical staff, rigorous corporate taxation, passing the social housing law, energetic discussions about the future of labor, investments into green energies and ecological agriculture, the fight against rampant foreclosures, animal rights, a clear pro-European party line – what more could a leftie want? After the party had been run for years by a rather centrist-right wing, which even led to the party taking part in the cuts and anti-social measures of Mirek Topolánek’s right-wing government in 2007, the leftist platform of the party, led by the young and energetic Matěj Stropnický, did an enormous amount of work to put the Greens back on a progressive track.

The majority of our editorial team as well as our readers will evidently be voting for them – except for our colleague Šplíchal, who recently came out as a reluctant voter of the Social Democrats (but only if he doesn’t get too drunk before the election). Does it all sound just wonderful? There is a huge catch. Voting polls are projecting around a 2-3% win for the Greens. Despite its new platform, the party hasn’t managed to escape its bubble of internet-generation hipster urbanites and social liberals. In the heyday of populists brandishing issues of security, militarization, the refugee threat, and Brusselsian red-tape, topics like the humane treatment of chickens will not win the election, unfortunately – for now.

Veronika Pehe

The Pirate Party

The Pirate Party

So far, the activities of the Pirate Party suggest one of the biggest surprises of the upcoming Czech parliamentary election. The Pirates are siphoning off the voters of primarily liberal parties – be it the neo-liberally oriented TOP 09 or the pro-social and eco-friendly Green Party. They’ve had the most success among the youngest voters and inhabitants of the largest Czech cities. It was only a year ago that there had been speculations about the Pirates forming a coalition with the Greens for the ensuing election, but the Pirate Party rebuffed this arrangement. They launched their campaign under the banner “Ecology without Ideology,” evidently signaling their divergence from the Greens, who are now left to occupy the political space of “ecoterrorists.” Despite the slogan itself making little sense, it represents the Pirates’ successful election campaign, which is doing a good job of explaining plainly and effectively some of the topics of the liberal left.

It gets a bit trickier in other areas. Despite Ivan Bartoš, the leader, being a trustworthy and promising politician, some of the members harbor weird libertarian opinions – especially regarding so-called platform capitalism. Some of the party’s IT solutions to the Czech state administration are a justifiable cause for concern to left-wing voters. Other liberal-minded voters fear the proximity of some party members to pro-Russian and conspiracy circles. Even though such individuals rarely operate in the Pirate Party, their activities hardly evoke the image of a coherent party with clear-cut priorities. Nevertheless, the potential success of the Pirate Party probably stands to be the only silver lining awaiting the Czech Republic in the coming election.

Jan Bělíček

**

Translated by Tereza Novická.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)