To clean or not to clean

Prague’s statue of Soviet Marshal Ivan Stepanovich Konev — a man known locally as “the Bloody Marshal” for his role in the 1956 Soviet invasion of Hungary — keeps getting in the way of spray cans and flying buckets of paint. Now — apparently sick of constantly having to wash a deeply unpopular monument — the local government has announced that the statue will no longer be their problem as they’ve offered it to the Russian embassy to be safe from further transgressions — and more importantly, out of sight.

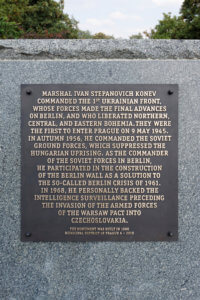

Yet the embassy has — rather predictably — refused the gift. Instead, they’ve claimed that the blame for the acts of vandalism and the obligation to clean them up lies with the district council who in 2018 replaced the statue’s original pro-Soviet explanatory sign with one slightly more related to actual history. Ondřej Kolář, the head of the municipal district where the statue is located, has in turn refused to accept the embassy’s refusal. And here things get a bit hectic.

Picked up by various media outlets, the story has now attracted just about every politician with a social media account and they’ve dedicated themselves to either pandering to the pro-Russia crowd or echoing the more widespread anti-Russian sentiments. Meanwhile, some members of society have decided to take the matter into their own hands. Recently, a group of pro-Russian activists tried to clean the statue themselves only to be interrupted by the police. Kolář, in response, announced a truly genius solution to protect the statue: cover it.

The covering tarp went up on August 30, but has not lasted. Another pro-Russian activist tore it down shortly after it was installed; He claimed that with the statue behind a tarp, some unspecified brainwashed youth could vandalize it with impunity.

The argument around Konev has even made the news in Russia. On September 6, the Russian culture minister joined the fray and called Kolář a Nazi for trying to get rid of the statue.

Cosmopolitan nationalism

If this all sounds silly and irrelevant, that’s because it should be. The district hall’s refusal to pay for the statue’s cleaning reeks of political theatre: a shallow attempt to attract a few more liberal votes by displaying a strong anti-Russia stance. But at the same time — due to the attention of extremist groups — the argument around the statue also presents a unique opportunity to probe the political interests of various coalitions operating in this country. As a recent protest illustrates, the plight of Marshal Konev has the undivided attention of actors across the Czech political spectrum.

Indigent about either moving or not moving the statue, protesters converged on Prague September 2 in the most eclectic gathering of nationalist crackpots the Czech Republic has to offer. There were: friendly — mostly communists — politicians; wannabe militia groups; pretty much the entire Czech disinformation scene, including the President’s press secretary and the local version of Sputnik; and of course, enough flags and banners to make one’s eyes glaze over.

Czech and Russian flags were to be expected and they appeared in bulk. They were joined by the more interesting emergence of Soviet flags, which swayed alongside Christian slogans and even the flag of the Workers’ Party of Social Justice (DSSS) — the successor to a banned neo-Nazi political party. The march thus managed to find the point where communism and nazism meet: Konev’s statue, Prague. A counter-protest added EU and NATO flags to the mix and someone even brought that Czech protest staple: an Israeli flag. It was a rather ideologically cosmopolitan meeting.

If nothing else, the protest showed a rather peculiar unity. All involved parties shared certain qualities: specifically conservatism and a quirky form of pan-Slavic nationalism.

A Russian out

In order to deal with the statue’s status, the district council will debate the issue over the next week. What will happen to Konev still remains uncertain. There are rumors that the late marshal’s daughter wants to move the statue to Moscow, thus fulfilling Kolář’s desire to be rid of it while providing an excuse that could potentially be good enough for the protesters . If this does not pan out, the best bet is to wait for everyone to calm down — until someone inevitably dumps a bucket of paint on Konev again.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)