On Saturday, 26 May, Krytyka Polityczna is launching its third festival of talks, debates, and events, named after Polish dissident Jacek Kuroń. The festival will take place at a number of locations across Warsaw and is dedicated to the topic of the crisis of democracy. It explores the sources of authoritarian developments, xenophobia, and the lack of solidarity in Poland and Europe, and measures the limits of civic engagement in the contemporary state, while also looking for traditions that will help to build citizens’ subjectivity. Visit the festival’s website and view the full programme here.

***

Mislav Marjanović: How did you come up with the idea to name the festival after Jacek Kuroń? Why is Kuroń so important for Krytyka Polityczna?

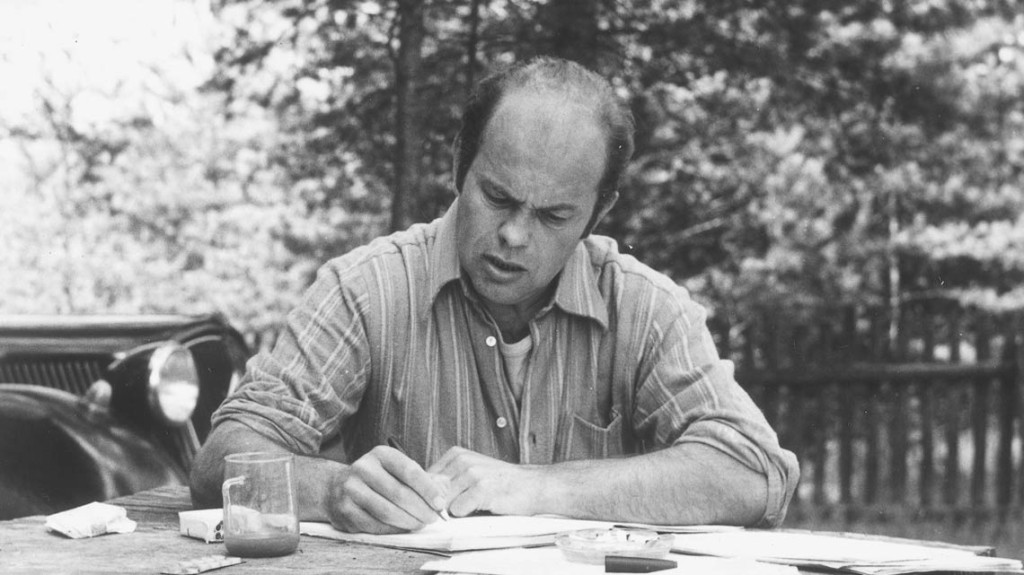

Michał Sutowski: Jacek Kuroń was among the key figures of the Polish democratic Left in the second half of 20th century and later, widely acknowledged as a historical hero and authority. But on the other hand, he is rather more admired than he is read and listened to – a sort of icon of a “good man in politics”, but without much attention given to what he actually wrote as an intellectual and how he worked as political activist.

Michał SUTOWSKI

is a political scientist and a columnist of Dziennik Opinii. He is a coordinator of the Institute for Advanced Studies, a translator from English and German, and an editor of the political writings of Jacek Kuroń and Stanisław Brzozowski.We believe that Kuroń embodies the crucial combination of three features significant for every leftist zoon politikon: first – values of equality, solidarity and democracy; second – ideas and theories of how to organize people for democratic politics; and third – the political practice of inspiring, educating, and engaging circles of people and individuals to make the world better. His values were were always constant, though his ideas and practice took different forms in different times. Kuroń always reflected on the specific historical context in which we need to look for the most appropriate form of political action. In the 1950s, he was the leader of the “red scouting” troop “Walterowcy”, educating children towards radicalism and non-conformism in the name of an egalitarian society. In the 1960s, together with Karol Modzelewski, he wrote the revolutionary-revisionist Open Letter to the Members of the Polish Workers’ Party, in which they called for an anti-bureaucratic workers’ revolution. In the mid-1970s, he became one of the co-organizers and leading intellectuals of the democratic structures of “independent society”, helping oppressed workers; he then became a charismatic figure in Solidarność movement during the time of “carnival” 1980-81, as well as one of the crucial actors in the process of the peaceful transformation towards liberal democracy (the so-called “Roundtable Talks”). And close the end of his life, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, he started looking for a new forms of political action and involvement of the people, being one of the first figures in the Polish mainstream to look towards alter-globalism and new social movements as a way of changing the world for the better. Recounting his biography very briefly is the best way to explain why he is important for progressive circles in Poland…

And he is an important figure for the contemporary Polish Left. What were his crucial left-wing political ideas?

He was a political activist always in touch with the changing course of events and the trends emerging in our society. Nevertheless, if I had to name what was crucial for his way of thinking throughout his life, this would be educating people and engaging the people in non-conformism through collective action rather than pure ideas and theory. He further believed in the inseparability of human equality from the possibilities of participating in social life, i.e. no “egalitarianism imposed from above” and, last but not least, he believed that the world around us is always a challenge in terms of values and utopias – but never the ones fulfilled by force or violence. This is crucial – he was very much upset and confused with his own past, feeling guilty for engaging with the communist regime in the 1950s; he gave his testimony on that in a brilliant book called Faith and Guilt.

But on the other hand, Kuroń’s political actions after 1989 were very controversial. What I mean is that he played a crucial role in implementing the harsh neoliberal economical program that was later called the “Balcerowicz plan”. How do you comment that?

This is true – there was a kind of interlude to his purely leftist engagements, namely between 1989-1993. His motivation then was to take responsibility for the country’s transformation from a collapsed, socialist command economy towards capitalism – as one of the leaders of the democratic opposition in the 1980s, he didn’t want to abstain from reforming the state and the economy when the communist regime lost its grip on the country. Nevertheless, he desperately tried – as Minister of Labor – to organize some safety net for people suffering from the collateral effects of the shock therapy he himself authorized and helped to impose. A few years after that, Kuroń became one of the toughest critics of these neoliberal reforms, being also aware that they probably wouldn’t have happened without his contribution – this is what their real author, Finance Minister Balcerowicz openly admits as well. Until now it is a matter of controversy, how much of the social costs were necessary and unavoidable in the process of reforms and to what extent were they actually successful. And Kuroń blamed himself – sometimes even over-exaggerating – for the pain and suffering the transformation brought to the Polish people.

So some kind of self-criticism?

Yes, but this was not only an intellectual, not to mention moral critique – he also worked on making the transformation a more participatory process. Since the early 1990s, he tried to involve workers and trade unions to be part of the privatization and restructuring process in former state-owned companies. He achieved at least some success in forming institutions of social dialogue – a tri-partite committee of unions, employers, and the state, which became a part of Polish political landscape for quite a long time.

What is the importance of Kuroń beyond the rather small left-liberal circles, like for example Krytyka Polityczna, the mainstream liberal newspaper “Gazeta Wyborcza”, founded by his friends from the opposition, or the leftist party Razem, whose leader was his young collaborator in the late 1990s?

I would say that it depends on the generation. For the older generation of politicians and public intellectuals, he was a very respected person on all sides of the political spectrum. For ordinary people, he was perceived quite commonly as someone who tried to give a “human face” to the transformation. Not least because of his famous charity events and TV program, in which he explained to the public the reforms introduced by his government, but also because as the Minister of Labor, he introduced an unemployment benefit, which in the early 1990s even got the name “kuroniówka”. For the younger generation, he’s mostly a part of history – this is why we want to “bring him back” by publishing his writings, wearing t-shirts with his most famous slogan – “Don’t burn the committees, set up your own ones” – and organizing an annual event dedicated not only to his life and work, but also treating him as an inspiration for thinking about and working on contemporary challenges.

And finally, what is the main concept behind this third edition of the Festival? Can you briefly describe the main parts of the program?

The general idea of the Festival is to discuss and present contemporary questions and issues from the perspective of values such as democracy, equality, and solidarity. Today, the main problems are the rise of nationalism, mostly – but not only – in Central Europe, the crisis of European integration and the European political model, as well as the limits of democratic agency within the nation state. We’ll discuss that with brilliant intellectuals like Claus Offe and Jadwiga Staniszkis, with leaders of the young generation of Polish politics, as well as with social scientists and artists. Every year, our Festival is not only about debating, but also about performing in the open space – the artistic reconstruction of the Round Table by the group Komuna Otwock is the crucial event this year. It is this episode in Polish history and Kuroń’s life that we want to rethink and elaborate – what is the core idea that we can draw from that moment, beyond the typical Polish dichotomy of an elitist conspiracy against the nation and the idyllic, foundational myth of a peaceful transformation towards freedom.

***

Read more:

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)