The architect Gabu Heindl and the artist Eduard Freudmann won “From Those You Saved”, an international competition to “commemorate Poles who rescued Jews during the German occupation”.

“If I am not for myself, who is for me?

And if I am only for myself, what am I?

And if not now, when?”

Chapters of Fundamental Principles (Pirkei Avot 1:14)

“Do not scorn any man, and do not discount any thing.

For there is no man who has not his hour, and no thing that has not its place.”

Chapters of Fundamental Principles (Pirkei Avot 4:3)

“The Monument

… is a Dilemma.

… is a Forest Nursery.

… is a Process.

… may be a Forest.

… may be a Failure.”

Title of the winning proposal to commemorate the Polish Righteous

The Monument Initiative

The idea to dedicate a monument in Warsaw to the commemoration of the Polish Righteous gentiles was first presented by Children of the Holocaust, a Warsaw-based association of individuals who survived the Shoah as children, many of them with the help of Righteous gentiles [1]. The idea was then adopted and promoted by Sigmund Rolat, a Polish-American philanthropist and Shoah survivor who has been very engaged in commemoration activities in Poland during the last years. He announced he himself would donate and fundraise money to cover the costs of the monument. His initiative received the support by the then-president of Poland, Bronisław Komorowski. However, it also faced strong criticism from Jewish-Polish intellectuals due to its envisioned location in the district of Muranów, the former Warsaw Ghetto. Today this neighborhood is not only a residential area but also the focal point of Warsaw’s Holocaust commemoration landscape and the site of the much-heralded POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Rolat proclaimed that the monument was to be built in close proximity to the two memorials to the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (built in 1946 by Leon Suzin and 1948 by Nathan Rapaport) and to the recently opened (2013) POLIN Museum. However, critics argued that the area should be reserved for the commemoration of Jewish suffering and moreover was already overburdened with non-Jewish monuments; Polish heroism should be commemorated elsewhere. Rolat, nevertheless, insisted on the location mainly for reasons of representation and attendance figures: “The location of a monument raised much controversy in our circles. I was convincing others that the monument, if it was erected somewhere else, would be visited only by a small group of museum visitors, maybe by every twentieth visitor, who would take the trouble to see it and learn about the righteous” [2].

[easy-tweet tweet=”Despite the quarreling, everybody agreed on the idea that the Righteous deserve commemoration” user=”krytyka” hashtags=”politicalcritique”]

But Rolat’s arguments were not perceived as convincing and many Jews of Polish descent from all over the world fought against the envisioned location: critical Facebook groups were launched, newspaper articles written, statements by intellectuals, rabbis and Jewish leaders were collected.[3]

Despite the criticism, in 2013 Rolat established the Remembrance and Future Foundation for the purpose of organizing a competition called “From Those You Saved”. It aimed to build a monument “to all the Poles who rescued Jews in German-occupied Poland”, located “in the Muranów district of Warsaw, Poland, in the vicinity of the Museum of the History of Polish Jews” [4]. But there was a catch, the title of the monument initiative was deceiving: “From Those You Saved” implies that there is a We, a community of survivors and descendants which desires to express their gratitude to the righteous gentiles. But this community does not exist, because the Jews who identify with the purpose of the monument are bitterly divided.

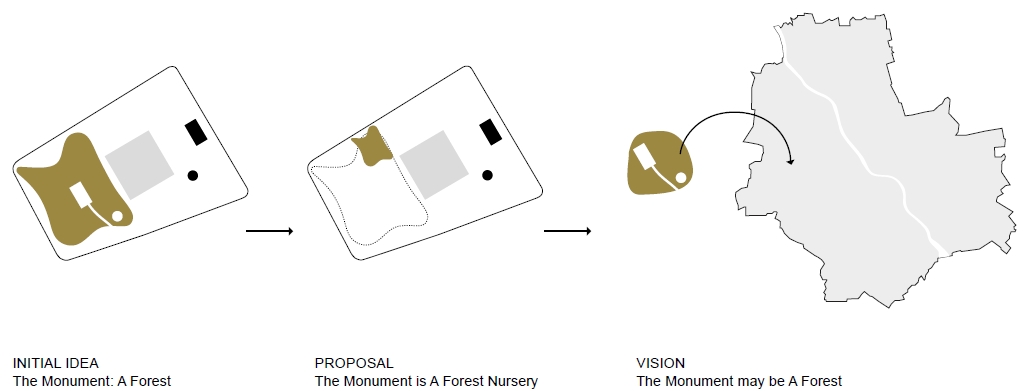

The Monument may be a Forest

Without knowing much about the criticism of the monument initiative, we participated in the competition and proposed a large urban forest to be planted in the park next to the POLIN Museum (the site proposed in the competition brief). After being selected for the shortlist of five finalists, we began to hear and learn more and more about the controversy. Initially we considered withdrawing from the competition but then opted against taking the easy way out. First of all, we appreciated the fact that the initiative was not set into motion by the Polish authorities, but rather by those who were saved, as its title asserts. And secondly, we thought that the situation was not so very terrible after all. Despite all the quarreling, everybody who had participated in the discussion thus far agreed on the fundamental idea of the initiative: that the Righteous deserve commemoration.

After a closer look at the situation we realized that first and foremost, erecting the monument is urgent. Time is passing, and 70 years after the end of Nazism, both those who saved and those who were saved are dwindling in numbers. Therefore the monument should be opened as soon as is feasible. But there was a dilemma: this is not an easy task that can be rushed to completion. Erecting a monument “From Those You Saved” requires time – both for the creation of a We, and for joint decision-making regarding delicate and important issues such as to whom the monument is addressed [5] and, above all, the most controversial subject: selecting the best location for it. We believed that this dilemma was not a bitter pill to be swallowed but rather a unique asset that should be incorporated into the monument itself.

So we altered our proposal accordingly – the monument would be a process of multiple stages: At its grand opening, the monument would not be a forest but a forest nursery, the vision of a forest, located in a large, raised bed next to the POLIN Museum. It would consist of dense rows of two-year saplings of common trees in Warsaw; the tight planting pattern requires that the plants be re-located after two years if they are to continue to grow. After the opening of the monument as a forest nursery, a social discourse would aim to create the We and decide on the future of the monument as a forest – that is, enable it to become a forest – at an urban location in Warsaw to be decided. The monument would be not only the forest nursery or the forest itself but also the ensuing intermediate process. The inherent fragility of the nursery would be an intricate part of the monument, without which it could not achieve its full dimension.

The forest should be planted permanently by way of a participatory process, which includes members of the We and Polish civil society. It should be maintained and taken care of by the City of Warsaw and private volunteers, Jews and non-Jews, thus serving likewise as a litmus test for the Polish state and civil society as to the value, in their eyes, of the memory of the Righteous gentiles. The forest can bear any shape; it includes two glades which mirror the two monuments to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. These remind us of those who were not helped, those who were not saved and – in the case of a different permanent location – remind us of the place where the monument originated. The urban location of the forest is key, because it represents the alienating character of the helping action, of the saving, which was only carried out by a minority of Poles who, in many cases, remained isolated after the end of the German occupation due to Polish anti-Semitism. If the We fails, there will be no forest and the monument fails as well. This failure would manifest itself in the diminutive nature of the forest nursery, which would never become a forest and in the ephemeral nature of its trees, which would not have space to grow. The potential inability to express gratitude as a We was thus an intrinsic feature of our entire proposal from the outset.

The Monument may be a Failure

The competition jury [6] selected our proposal as the winning project. This transpired against the recommendation of Sigmund Rolat, who attended the jury meeting as a guest and declared which project he favored [7]. The events following the jury’s decision revealed the discomfort of the Remembrance and Future Foundation and its chairman. The press conference scheduled to take place immediately after the jury meeting in order to announce the result of the competition was cancelled last minute. Two days later, a press release was published: “The Board of the Remembrance and Future Foundation has been informed of the jury’s verdict, and will announce its own the decision [sic!] in due time” [8]. A week later an attempt to present our project as invalid followed: “Rolat, 84, told […] that the winning entry was ‘radically changed’ since its selection as one of the finalists […]. Therefore, he said, it was no longer a valid entry at the time of the judges’ vote. He called it a new, ‘sixth’ entry that could not be considered with the five original finalists” [9].

Although this statement was exaggerated and untenable, it became clear that Sigmund Rolat and his Foundation did not want to implement our proposal. Konstanty Gebert, the Foundation spokesman and member of the three-man board, informed us that we would need to radically alter our concept, otherwise the Foundation would not accept it. Our proposal to have a workshop in Warsaw to address the Foundation’s concerns was rejected as was our repeated request to meet personally with Sigmund Rolat in order to discuss our proposal. On July 31 the Foundation announced that the project selected by the jury will not be executed. A month later, Sigmund Rolat stated that he is “conducting serious talks with two or three artists” and that in the next two or three months it will be announced “who will design the monument and when it will be unveiled” [10].

Commemoration as Public-Private Partnership

When working with monuments in public space, one has to be prepared for anything. Due to the large number of stakeholders of public space, each of whom fights for their own interests, events often unfold unpredictably. Failure was one of the possible outcomes we inscribed into our project from the outset, embodied in the potential impossibility of creating a We which would succeed in making joint decisions regarding the monument. Eventually “From Those You Saved” has indeed failed, but for other reasons. In order to examine the failure, it is helpful to look at a specific characteristic of the monument initiative, namely that it is neither a purely public venture nor an exclusively private one, rather it is a public-private partnership commemoration project. This distinctive feature held significant potential for this project – to succeed as well as to fail.

Public-private partnership (PPP) is used to designate different forms of cooperation between public and private protagonists – mostly with regard to financing public goods or infrastructure, e.g. a school built by a private builder and leased to a public operator. There is a wide range of criticism of PPP projects concerning the concealment of contracts, lack of parliamentary control, corruption liability and a shortage of democratic legitimacy. The PPP structure can be limiting since private investors are frequently concerned with protecting their own interests from outside influence when critical questions or issues arise. This is highly problematic in the public realm, in academia, in contemporary arts and culture because the protagonists of these areas must be able to think critically and articulate openly. But what does PPP mean in the context of commemoration in public space? And why could it even be an interesting model for the Warsaw monument initiative?

Commemorating an atrocity such as the Shoah is not an easy task and requires enormous responsibility, especially when operating in public space. There have been many attempts by Polish nationalists to utilize the deeds of the Righteous Gentiles for their own political agendas, which in many cases are anti-Semitic or anti-Judaist.[11] Hence, most Polish Jews are quite sensitive and wary when it comes to that subject. The fact that the monument idea was brought up by a group representing individuals that were affected by the historical events at stake and pushed forward by a philanthropist who is a survivor himself was positive because it decreased the potential of political appropriation by nationalists. But it does not prevent it! Indeed, the danger of potential political appropriation or abuse was one of the controversies surrounding the monument initiative and the cause for the widespread disapproval of the envisioned monument location.

Let’s have a look at the protagonists of the PPP venture “From Those You Saved” and their specific makeup. The first P, the public protagonist, is represented by the Polish authorities, such as the Republic of Poland, the City of Warsaw and the Muranów neighborhood council. Their role is to provide a building site, authorize the monument design and construction plan, as well as to maintain the monument after its grand opening. The public authorities signalized their support for the initiative but kept a low profile while events were unfolding. According to the title of the initiative, the second P, the private protagonist, is represented by those who were saved and their descendants: the Children Of The Holocaust association (who came up with the idea), the Remembrance and Future Foundation (who turned it into an initiative), future donors (for whom Sigmund Rolat announced he would search) and other members of the Polish Jewish civil society who identify with the cause of building a monument to the Righteous and contributed to the discussion thus far [12]. All these protagonists coming together to partner in a monument initiative was a promising start for commemorating the Righteous in a meaningful way. Unfortunately things turned out differently.

Feudalism in Public Space

In the end, the PPP model did not work out because one of the protagonists acted self-righteously rather than in the spirit of partnership. Sigmund Rolat’s first mistake was to ignore the criticism surrounding the targeted site, uttered by a large number of renowned Holocaust studies scholars, historians and other experts from Jewish civil society. The brief of the international competition does not make mention of any other option for the location other than alongside the POLIN Museum. His second mistake was to attend the jury meeting as a guest and declare which project he favored, thereby attempting to undermine the jurors’ independent work. The third mistake was to dismiss their decision and neglect seeing that the selected project offered him the chance to correct his first mistake without losing face. But Sigmund Rolat’s probably most significant mistake was to appoint himself as the expert who shall alone decide on the monument design.

All these missteps were able to occur without the interference of any regulating factor. This sheds light on the danger of feudal mechanisms within PPP projects [13]. For it is nothing but a feudal act to override all existing rules and agreements made with the engaged public – this public included not only Jewish civil society and the competition jury but also the 136 teams of artists and architects from 16 different countries who invested their time, energy and money under the premise of participating in a serious competition [14]. Sigmund Rolat´s action clashes with the concept of a public monument because it is in absolute contradiction to a democratic understanding of commemoration and of public space, as public space belongs to a public (always to be created) and not to a single individual.

Furthermore, the evolution of the project initiative raises the very question of the responsibilities inherent in philanthropic engagement in public space. Philanthropists behaving as omniscient experts tend to appear somewhat eccentric. However, when operating in their sole field of responsibility, e.g. when building on their own piece of land, such behavior is legitimate; one might even look at it with sympathy and call it quirky. But at stake here is the public space of a European capital and moreover one of the most historically charged sites of the Shoah. This is not Sigmund Rolat’s backyard. A philanthropist who does not understand the difference between working in these two settings, and the implications involved thereby, misses his or her vocation. Sigmund Rolat should recall that the initiative he has chaired is called “From Those You Saved” and not “From Me, One of Those You Saved”.

The Monument is a Process

What will the future bring? Most probably Sigmund Rolat will do as he announced and present his personally-selected design for a monument located next to the POLIN Museum. We can expect a “traditional memorial of stone, steel, and concrete” [15] – monumental, representative and modernist. Whatever form it may take, if the Warsaw City Council has a spark of decency, it will not grant approval to Rolat’s choice for the monument in light of all the dubious missteps taking place during the PPP debacle and the global criticism of a monument on the specified site. However, it would be a pity if the monument initiative was dropped entirely since all protagonists agree that the Righteous deserve commemoration.

The realization of a contemporary, non-feudal manifestation of public commemoration is possible. The first and most important step would be the formation of the We consisting of survivors and their descendants, as well as institutions such as the POLIN Museum and the Jewish Historical Institute. It is crucial to address and include the third generation as well; there are some thriving organizations of young Jews in Poland. Whether Sigmund Rolat and the Remembrance and the Future Foundation will be a part of this We remains uncertain. This does not only depend on their readiness to accept being deprived of their unrestricted power but even more on their willingness to regard the other protagonists as equal partners and to negotiate their standpoints without a predetermined conclusion. The site of the monument would still be a key question debated by the We. Whether it will be inside or outside of the former Warsaw Ghetto remains to be seen. Of course it would be possible to stay with the proposal selected by the jury, especially since the monument initiative should proceed expediently due to the ageing first generation. Establishing the forest nursery could be managed with a rather small budget. Additional fundraising activities could be included in the process of negotiating the monument’s future; these negotiations can be carried out while the saplings grow.

But other good ideas also came up in the discussions around the monument. Ironically, one of them was contributed by the Remembrance and Future Foundation, which misunderstood our proposal and thought the forest nursery would remain at location and continuously provide commemoration trees to the entire country – since, after all, the history of the Righteous continues to be written. Someone else came up with the idea of creating a mobile monument which would travel the country while another person proposed to build 6,532 decentralized monuments, one for each of the Polish individuals who are recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem. Whatever may come, we hope that a manifestation of public commemoration dedicated to the Polish Righteous Gentiles will be opened as soon as possible, a manifestation that follows a contemporary and post-representational approach [16] to commemoration, incorporating a democratic notion of public space and – above all – a manifestation to which Robert Musil’s challenging dictum that “there is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument” [17], will not apply.

Read more:

FOOTNOTES:

[1]

The Children Of The Holocaust, A short history (retrieved Dec 21, 2015).

[2]

Piotr Karnaszewski: Raising Money For A Jewish Legacy, American Style; Forbes International, Nov 2, 2014.

[3]

For a collection of the extensive materials see the Facebook group “Czy upamiętnić Sprawiedliwych na terenie byłego getta” (“Should the monument

honouring the Righteous Poles be placed in the former Warsaw Ghetto”).

[4]

http://www.raff.org.pl/en#competition (retrieved Dec 21, 2015).

[5]

There are highly emotional debates on the question of how many Poles saved Jews. Yad Vashem lists 6,532 persons; Polish nationalists claim much larger numbers, e.g. the historian Jan Żaryn states “In my opinion, at least 1 million Poles provided [Jews] assistance.” (in Donald Snyder: Poland’s Dueling Holocaust Monuments to ‘Righteous Gentiles’ Spark Painful Debate; Forward, April 27, 2014; retrieved Dec 21, 2015).

[6]

The jury consisted of: Michael Berkowicz (architect, USA), Michael J. Crosbie (architect, USA), Jarosław Kozakiewicz (sculptor, Poland), Rainer Mahlamäki (architect, Finland), Marek Mikos (architect, Poland), Maciej Miłobędzki (architect, Poland), Oren Sagiv (architect and curator, Israel), Jakub Szczęsny (architect, Poland), Hanna Szmalenberg (architect and sculptor, Poland), Milada Ślizińska (art historian and curator, Poland).

[7]

Tomasz Urzykowski: Las pamięci Sprawiedliwych? Fundator niezadowolony; Wyborcza.pl, Apr 25, 2015 (retrieved Dec 21, 2015).

[8]

http://www.raff.org.pl/en#news (Statement published on Apr 4, 2015; retrieved Dec 21, 2015).

[9]

Donald Snyder: Warsaw Ghetto Memorial to Righteous Suffers New Setback as Design Is Tossed; Forward, May 2, 2015 (retrieved Dec 21, 2015).

[10]

Tomasz Urzykowski: Pomnik Sprawiedliwych przy Muzeum Polin. Jeśli nie “las”, to co?; Wyborcza.pl, Aug 31, 2015 (retrieved Dec 21, 2015).

[11]

To give an example: in addition to the monument initiative next to the POLIN Museum, there is another initiative for a monument to commemorate the Righteous. The organizers plan to build a sculpture in the form of a stylized ribbon in which the names of the Righteous would be engraved. The ribbon would be around two meters high and loosely wrapped around a church, providing sufficient space for tens of thousands of names (or more?, see footnote 5). Critics consider this initiative as an attempt to whitewash Polish anti-Semitism during the Shoah.

[12]

One of the most natural protagonists of the debates on the monument would have been the POLIN Museum, not only due to its close vicinity to the targeted monument site but especially because of its self-conception as a museum focused on Jewish life. However, the institution remained rather reluctant to participate (with the exception of its chief curator, Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, an outspoken critic of the initiative). Ironically this reluctance is a result of the museum’s very nature as a PPP project itself. Participating in the debates would bear the risk of harming the interests of one of its main private benefactors, Sigmund Rolat.

[13]

The “refeudalization” of the public sphere was described by Jürgen Habermas in 1962: “[The] public sphere of civil society again takes on feudal features. The ‘suppliers’ display a showy pomp before customers ready to follow. Publicity imitates the kind of aura proper to the personal prestige and supernatural authority once bestowed by the kind of publicity involved in representation.” (Jürgen Habermas: The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, Cambridge 1991, p. 195) In recent years, this notion has been used to describe the crisis of publicity resulting from its privatization and the power of the individual in oligarchic capitalism (cf. Sighard Neckel).

[14]

For a complete list of participants see page 149–152 of the competition catalogue “From Those You Saved”, Warsaw 2015. (retrieved Dec 21, 2015).

[15]

Liam Hoare: How Plans To Build a Monument to Righteous Gentiles in Warsaw Fell Apart; eJewish Philanthropy, Nov 8, 2015 (retrieved Dec 21, 2015)

[16]

The spatial manifestation of a monument is merely a snapshot in time. A monument is not only what you see, but also what it was previously, what it will be prospectively and the intermediate process. Therefore monuments are manifestations of processes, never to be conclusively determined but steadily open to re-negotiation and re-configuration. This fact should not be disguised but represented in the manifestation’s form. Instead of providing a certain reading and the respective image of history, a monument should aim at facilitating an “Auseinandersetzung” with history, meaning to look into and examine history as well as to debate and quarrel about it. Our approach to post-representational commemoration relates to the notion of post-representational curating, proposed by Nora Sternfeld and Luisa Ziaja: “Representation is replaced by process: rather than dealing with objective values and valuable objects, curating entails agency, unexpected encounters, and discursive examinations. […] Accordingly, post-representational curating creates spaces for negotiation, openly addressing contradictions within seemingly symmetrical relations. This also may involve conflict […].”(Nora Sternfeld and Luisa Ziaja: “What comes after the show? On post-representational curating”; “Dilemmas of Curatorial Practices, World of Art Anthology” ed. Barbara Borčić, Saša Nabergoj; Ljubljana 2012, pp. 62-64).

[17]

Own translation of: “Es gibt nichts auf der Welt, was so unsichtbar wäre wie Denkmäler.“ (Robert Musil, Denkmale, Prager Presse, Nr. 339, 1927)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)

Saying “thank you” is important for future genartions and the society as a whole. It sends a clear message that risking lives and helping others actually makes sense. That people want it, respect it and appreciate it. Right now it is not really clear if Jews really respect what (tens of thousands) Poles did and risked to help Jews. When I hear that (tees of thousands anonymous) Righteous Poles are “not worthy” to be remembered there near the Polin musem and Brandt monument, then it makes me speechless….

Stick your butt down your mouth and choke on it until you burst, dear Anonymous whoever. It is a noble thing to save a life; and it would seem only natural to show thankfulness to someone who have saved you. But then if you save someone, do you really do it expecting something in return? And is it still a noble thing to demand thanks when you have not been granted it? I thought many if not all those who helped the Jews did so because they thought it was the right thing to do. And you normally don’t want be repaid or recognized for things that you consider as your duty. Note that it usually the children or grandchildren of the Righteous who get them the title of the Righteous. Now tell me, do you ask thankfulness of Jews, because there were rescuers in your family who never seen their outstanding act of humanity recognized? If so, I might be more compassionate about your position: after all it comes as an obligation to save one’s parents’ or loved one’s good deeds from oblivion, to save a good human being’s example from oblivion. This is an honourable cause. But if you are not heir to people who themselves helped the Jews, then I find your comment more in line with some Poles’ hearty rooting for a special status of the Poles as the impeccable yet wronged nation; then your comment can be read as an example of a tribal drive to have your tribe well spoken of, as if its great ones’ splendor shed some of their glory on you. Indeed, we always seem so concerned about being slandered, portrayed in unfavourable light that I tend to believe that some sort of this my-nation-had-great-people-so-I-can-feel-superior thinking is at play here. Please wake up to the fact that you have no right to use other people’s righteousness as an advertising commodity to promote your country abroad and boost you self-importance. I mean, you may do it, as it’s being done, in a more or less shamelessly vulgar way, by the governments and businesses of many countries (be it Poland, Israel, USA, Germany, France, and the list may go on), but it won’t take you much further than closely-walled national sentiments. Now, I don’t know about the Jews, but as for the Poles, it seems to me it is them (not all, but there is a conspicuous enough representation of individuals I am pointing to) who behave as if they were peculiarly fond of their own victimhood. Martyrdom. Or heroism (usually not the advocate’s personal heroism, and often not their personal martyrdom, and yet they advocate for its recognition with such a zeal that you might think they have some personal meat to cook here).

Stick your forrest in your butts, dear Jews. Forrest simply means, that you do not want a monument there. Becasue you can’t accept a symbol which turns Jews into people who owe something to Poles. Jews want to feel morally superiour in Poland. A nation of “victims” and nothing else. Not a nation of collaborators (see Zagiew) or people who recieved (some kind of) help from (hundereds of thousands of) Poles during the Soviet German occupation. No, all you want is 100% victimhood. Saying thank you to Poels makes you sick. It’s actually much easier for you to say thank you to the German. No wonder you do not protest against the Willi Brandt momument.