On a bitterly cold day in December 2010, I, along with a group of colleagues from the Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk drove fifty kilometers to Kocborowo (formerly known as Konradstein), a hospital for the mentally ill that participated in the Nazi euthanasia program. We were not sure exactly what we would find in its old halls but we were excited about the possibility of locating artifacts that would help tell the story of World War II. While walking through the storage halls, we came across an old and rusty chair for a handicapped person. It clearly had a long history that we desired to unravel. After a conversation with the hospital authorities and a careful verification process, we established that the chair was produced before the war and had been part of the hospital equipment during the war. It immediately became one of the first artifacts of the museum’s permanent exhibit that in 2010 was still in the stage of conceptualization. Even though this particular moment felt like a miracle, it was only the beginning of a stream of important discoveries.

I, along with other museum workers, spent countless hours searching for such artifacts as the chair throughout Poland and beyond. We were part of a small and close-knit team of historians, mostly Ph.Ds. and Ph.D. students, fascinated with the prospects that the project of creating one of the biggest museums focused on the Second World War opened up for us. The geographical and conceptual scope of the institution seemed astounding. The initial group consisted mostly of Polish-born and Polish-educated historians, except for me, a graduate of Indiana University in the USA, and Daniel Logemann, a German-born and German-educated historian, who devoted his professional life to studying Polish and Polish-German history. I was a native to Gdańsk, the city I feel deeply connected to. In 2010, I was in Gdańsk on a Fulbright scholarship while finishing up my dissertation and raising my daughter and infant son. As soon as I heard that the museum was hiring I knew that I needed to become involved. I began working there in the summer of 2010, and after a year of intense work, I continued to collaborate with the museum despite moving to the United States. I like to think that I was part of the beginning phase of its most intense development. What we historians all had in common was energy and a passion for history. Our expertise in historical fields differed—archival work, military history, diplomacy, gender. Those differences, however, made us depend on each other for skills and knowledge

Like the chair, each of the artifacts that we collected had a distinct story to tell. In late December 2010, for example, my colleague Daniel Logemann and I participated in a post-Christmas opłatek celebration at the local Association of Former Prisoners of the Concentration Camp Ravensbrück, where former prisoners drank tea and shared leftovers of Christmas cakes. We met Mikołaj Skłodowski, the local priest of the Polish National Catholic Church and one of the last children born in Ravensbrück. His mother, a former Ravensbrück inmate, was still alive but in very bad physical shape; she slept on the days we visited Mikołaj. During the first meeting, Priest, as we began calling him, showed us a little medallion of Saint Nikolaus (Mikołaj) that his grandmother had brought from Saint Petersburg (her family escaped from St. Petersburg in 1917). His mother had later carried this medallion hidden in a bar of soap throughout her stay in Ravensbrück, where she was taken after the fall of the Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Priest, her son, who was born in March 1945, has taken the name of the saint on the medallion—Mikołaj. When he was born, the war was drawing to a close, and that was the only reason why Mikołaj survived. In April, he and his mother, along with other women, were evacuated to Sweden, where he was eventually baptized. His small, still-white baptismal robe and other baptismal gifts including children’s utensils, as well as the medallion, became the possession of the museum.

A couple of years later, I met with Anna Jarosky in New York to take over one of her most valued possessions that had belonged to her mother Jadwiga Dzido, who was one of the Ravensbrück ‘rabbits’ (women who had their legs cut open and experimented upon). During the meeting, Anna told me: “I was waiting for a place in Poland that would be interested in this part of our history; people who would come and ask.” Whilst handing me negatives of the photos of the mutilated legs that the women had taken with illegal cameras in the camp, she said: “It was not about their humanity, about big words. It was about normal life.” Further, she narrated how her mother, who had severely damaged legs, used to cover them with special tights that helped to fill up the holes created by surgery in order to not draw attention to her suffering. The photos that she and other ‘rabbits’ took present young, beautiful, and even at times smiling women, who in a shy gesture show their legs as evidence of the crime. They point at a crime, in general, rather than at their particular individual suffering. And that’s the message that Anna Jarosky passes on: that even though these women had to face adversity their entire life, they remained cheerful and happy. The war affected them, but it did not define their lives; rather than the suffering of the war, it was in fact the decision to smile while taking illegal photos in extremely dangerous conditions that defined them. The importance of this spirit was something that they passed on to their children.

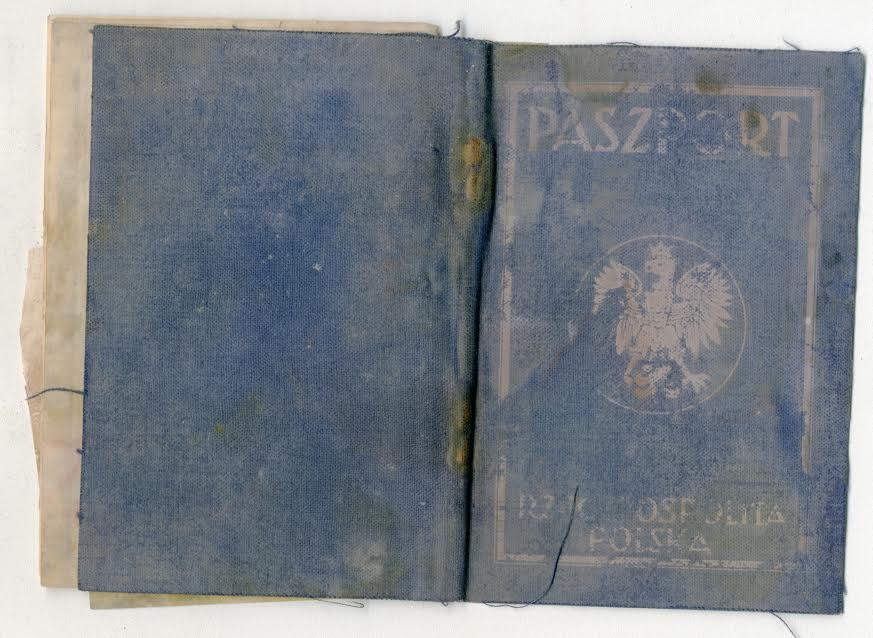

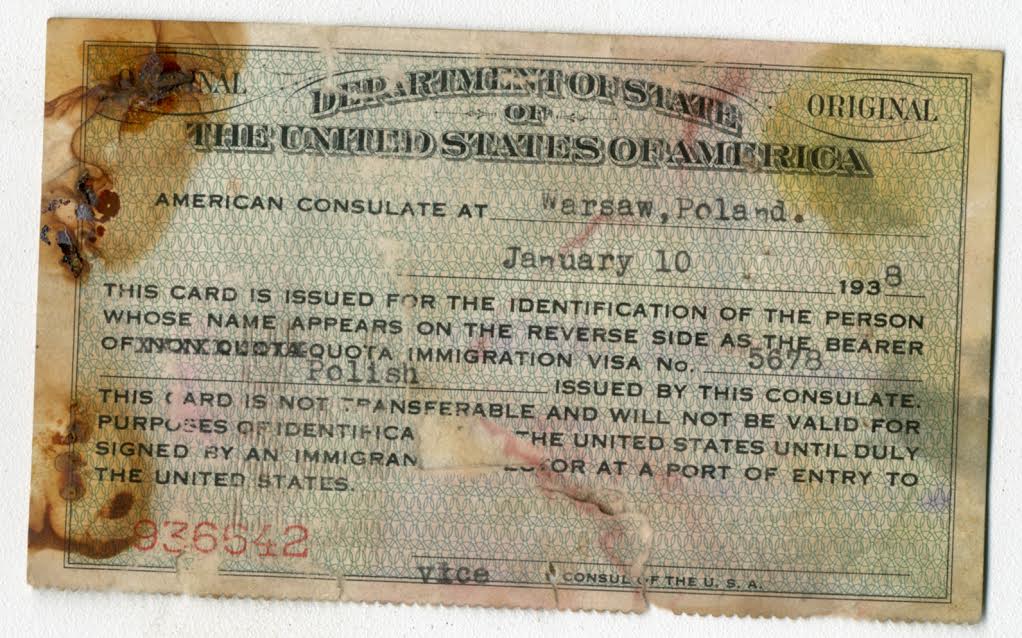

In 2009 or even in 2010, we had little hope that there were still significant artifacts to be recovered. However, the results of our national call for artifacts, which was first announced in October 2011, showed unanticipated support and endorsement of the museum. Five years later, in 2016, the museum has at its disposal over forty thousand pieces of memorabilia and historical artifacts. Thirteen thousand of these items were donated. What in 2010 seemed like a dream, in 2016 became a reality that exceeded everybody’s expectations. It was the people who made this possible. People such as Mikołaj and Anna: their motivations of donating to the museum, the objects that they entrusted us with, and finally their stories of the objects delineated the scope of the exhibition and showed the complexity of the war. For example, Jacob Baker’s (Jakub Piekarz) family entrusted us with important documents that shed light on the complex context of the war. Baker left Jedwabne in 1938 for New York on Batory, an ocean liner that was taking emigrants to the new world. One of his older brother was already there. His mother, second brother, and more distant family stayed behind. After the war, Baker repeatedly sent telegrams to Jedwabne in search of his family. He finally learned from his brother who survived the war in Poland about what had happened in Jedwabne in July 1941, when Poles murdered their Jewish neighbors. His story became the foundation of the book Neighbors by historian Jan Gross. Baker hesitated visiting Poland after the war, but he finally did visit Jedwabne in 2001 in order to participate in the 60th anniversary of the massacre. Over a decade later, after some hesitation, his daughter handed me his archives, containing letters, photos, and the passport that helped him leave Poland just before the war began. She believed that the photos and documents should be testimony to the common Polish-Jewish life in a place that both groups called ‘home,’ that this evidence points to shared living space and mutual understanding prior to the massacre, and finally that understanding the complexity of historical context may help build bridges for the future.

Unfortunately, the museum’s future and its primary vision are currently in jeopardy. On September 6, 2016, the Polish Minister of Culture, Piotr Gliński, announced his final decision to continue with the plan, that surfaced earlier this year, to merge the Museum of the Second World War with the Museum of Westerplatte, a new museum created earlier this year. The Museum of Westerplatte results from a new historical policy that the current Polish government of Law and Justice embraces. The policy aims to control the narrative of the 20th century in such a way as to glorify and exonerate Poles. The new historical offensive that President Duda announced earlier this year calls for reaction whenever the Polish nation is humiliated and its historical heritage depreciated. According to this line of thought, insult comes with distorting history. Unfortunately, the scope and the international perspective of the Museum of the Second World War awakens anxieties that it may insufficiently showcase the Polish point of view. The criticism that the state officials leveled at the Museum of the Second World War raises the objections that while focusing on the inferno of the war, it blurs the unique nature of the Polish theatre of war, with its suffering and heroism.

Despite maintaining the old name, the new museum is destined to become an institution with a new vision. It is too early to tell how much the new will differ from the old: possible changes include the replacement of the current leaders and creators of the museum with new management, perhaps the hiring of new staff members, and finally—and most concerningly—significant changes to the main exhibition, on which production is already almost finished. The institutional change also means the end of certain hopes that to my knowledge guided the majority of the people working for the museum since its inception in 2008, hopes that there is a way of maintaining a unique Polish viewpoint while engaging in dialogue with broader European perspectives on the Second World War. Unfortunately, it also means abandoning the people whose support and donations helped delineate the visual as well as the conceptual scope of the main exhibition. The main exhibition is not a result of arbitrary decisions made by historians working there, but rather of careful and deliberate planning based on continued dialogue with scholars and curators from all over the world along with a careful reading of the historical artifacts as voices that led Poland through complex dimensions of the war. Steering the historical exhibition towards a top-down understanding of history denies the voices of the people who experienced the war. The objects and their stories evade any definitive ‘truths’ that critics of the museum would like to see unfold in the exhibition; they certainly add nuance and an individual agency, at times making it more complex, and perhaps also more ambiguous, but certainly more pluralist.

Daniel’s critical and sober approach to Poland’s fascination with heroism and bloodshed for the nation often led to intense and heated debates among the historians working there. As many of us soon found out, his point of view was not unique: during many international workshops, meetings, and study sessions, members of our team were faced with questions and doubts about what seemed to us to be an innate Polish sense of uniqueness, heroism, and martyrdom. Each day we learned that it was not enough to insist “on marching to Europe together with our dead,” as Polish literary critic Maria Janion characterized Polish historical memory in the early 1990s. At times, it was puzzling when it seemed that years of education about being a victim of history instilled in us a perception that uniqueness is better than being average—or normal—like other European countries. Consequently, each of us had to go through an intense and at times overwhelming learning process, which forced us to face almost daily our own stereotypes, disentangle historical inaccuracies, and struggle with how to distinguish complex and often troubling labels.

Perhaps the biggest challenge for the majority of the people working there was scenography. In the end, most of us were historians trained in thinking through a written text, not historical artifacts or a museum scenography. It is tempting in a modern museum to rely heavily on theatralization and multi-media, which can be indulgent with almost limitless text and multi-layered organization. Critics accuse us of not specifying the audience. In reality, however, the audience was the beginning and the end of most of our discussions. We viewed the audience either as Poles who know or think they know ‘everything’ about Poland’s history or as an average foreign visitor, whom we had to attract and teach without being overbearing. Throughout the process, we felt like real Europeans who were entering into a dialogue that was educational for both sides. The tools that helped us speak were historical artifacts that combined historical authenticity with interesting and educational narratives. While providing us with an individual dimension of the war, these tools ultimately exposed us to a multidimensional context in which all the stories unfolded.

When I asked various colleagues in the museum about their favorite artifacts, they pointed at many objects: an English teddy bear that was handmade from scraps (wartime shortages forced English men and women to ‘make do and mend’), Christmas ornaments made of wood and paper by a Polish family deported to the depths of the Soviet Union, a camp spoon sharpened from scrubbing a bowl, and a genuine German Enigma machine, donated by the Norwegian Armed Forces Museum. Most of these objects speak to us about depravation and misery in a direct way. They invite us to think about and imagine the horrendous daily wartime realities. They may even push us to draw wider theoretical reflections on ‘bare life’ in Georgio Agamben’s understanding of life being devoid of respect and representation: life reduced to physicality. Some other artifacts speak of heroism and creativity. But such reading alone runs the danger of telling the life of an individual through the prism of one particular object, reducing life and war experience to one specific artifact.

I prefer to think of objects as artifacts that testify to a skill (arte) or some kind of cultural norm that guided their production, their utilitarian character (facare: to make or do), and also the individual creativity and perseverance that connects the two, arte and facare. The artifacts we collected speak to the significance of war, to its singularity as an event for almost everybody involved. True artifacts, hidden behind a glass display, may appear detached from their larger significance. But the setting, the context, and the story that they accompany—or the story they reveal—can help turn them into a medium that conveys its own meaning or significance. Rather than being static objects that invite contemplation and even veneration. They are historical events that speak about ways of living, but also about something even less tangible; about an individual dimension of the cataclysm of war. The objects did not speak to us about the past, or at least not only about the past, but more so about the present. They had an emotional as well as an epistemological value, and we treated them as a source of knowledge about the past that the people wanted to maintain. They present us, those who listen, with a more pluralist voice on the essence of heroism, where rather than suffering, we see individual desire to keep on living. Rather than a black and white response to the war, we see the diversity of experiences.

The richness of the exhibit at the Museum of the Second World War should be revealed. It should have a right to speak with its pluralist voice about the ghastly nature of war and the complex, diverse, and multifaceted individual responses. Artifacts speak to us through at times bizarre suspension between cruel realities and individual responses to them—something belonging to the realm of necessity and realm of freedom. The conceptual decision to make use of them as much as possible is strengthened in some sections by the presentation of icons, real people whose lives and deeds ground the meaning of specific artifacts more firmly. The realm of necessities and the realm of freedom—horrible conditions of the war, individual perseverance, and individual decisions that are often seen as part of the continuum between good and bad—are all part of an internal dialogue that at times bear ambiguity and enlightenment. This ambiguity is not, as some critics of the museum claim, a result of conceptual problems, but rather a result of reflection on a war and the role of modern museology that combines emotional and intellectual messages to add nuance and to make us uncomfortable in order to pose questions and prompt reflection. The diversity and the richness that artifacts carry also tell us something unique about the daily heroism and the martyrology that we Poles hold so dear to our lives.

***

The author would like to thank Bartłomiej Garba, Łukasz Jasiński, Waldemar Kowalski, Daniel Logemann, and Jan Szkudliński for sharing their stories with me. Thanks are also due to Basia Nowak for help with earlier versions of this text.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)