The essence of Kraków is Old: layers upon layers of Norman, Gothic, baroque, Renaissance, neoclassical, Victorian, art nouveau, renovation, decay, restoration, war, more decay, redecoration, vandalism, remodeling, additions, weatherings, losses, reclamations, now all cross-seasoned in one magnificent Polish bigos. Kraków is Old old enough to be just a little fallen, and thus not as full of itself as Warsaw, an easy city to live in and with. Kraków is Old old enough to be comfortable with itself, and thus graceful and unstressed, a self-assured and reassuring city. Kraków is Old old enough to have antiques behind the antiques: you can’t exhaust this town, and Kraków doesn’t have to throw what little it’s got in your face, hustle you with façade. Kraków is old enough to have survived centuries before you happened along; if you don’t care for this city, Kraków will get along for centuries without you.

Kraków is Old old enough to be just a little fallen, and thus not as full of itself as Warsaw, an easy city to live in and with.

Kraków is old enough to know quality when it sees it. Are you our sort of person?

Kraków is genuine Old: the Germans planned to destroy the city upon departure, as well you might expect, but liberating Soviet forces circled around the city and attacked unexpectedly from the west, while Polish agents within the city managed to disrupt explosives and detonating cables, sparing Kraków the horror which leveled the Warsaw Stare Miasto to a pencil line. Kraków is so full of Old that Old Town is under protection as part of the “World’s Cultural Heritage,” for whatever that’s worth. This UNESCO seal of approval and a strong army might allow Kraków to survive the next global catastrophe. Or it might not. One rather hopes it does: Kraków is incontestably one of Europe’s great cities. The powerful charge of planting one’s feet on stones where, five centuries ago, princes robed themselves for coronation, and potentates decided the fate of the world is not to be found too many places on this globe.

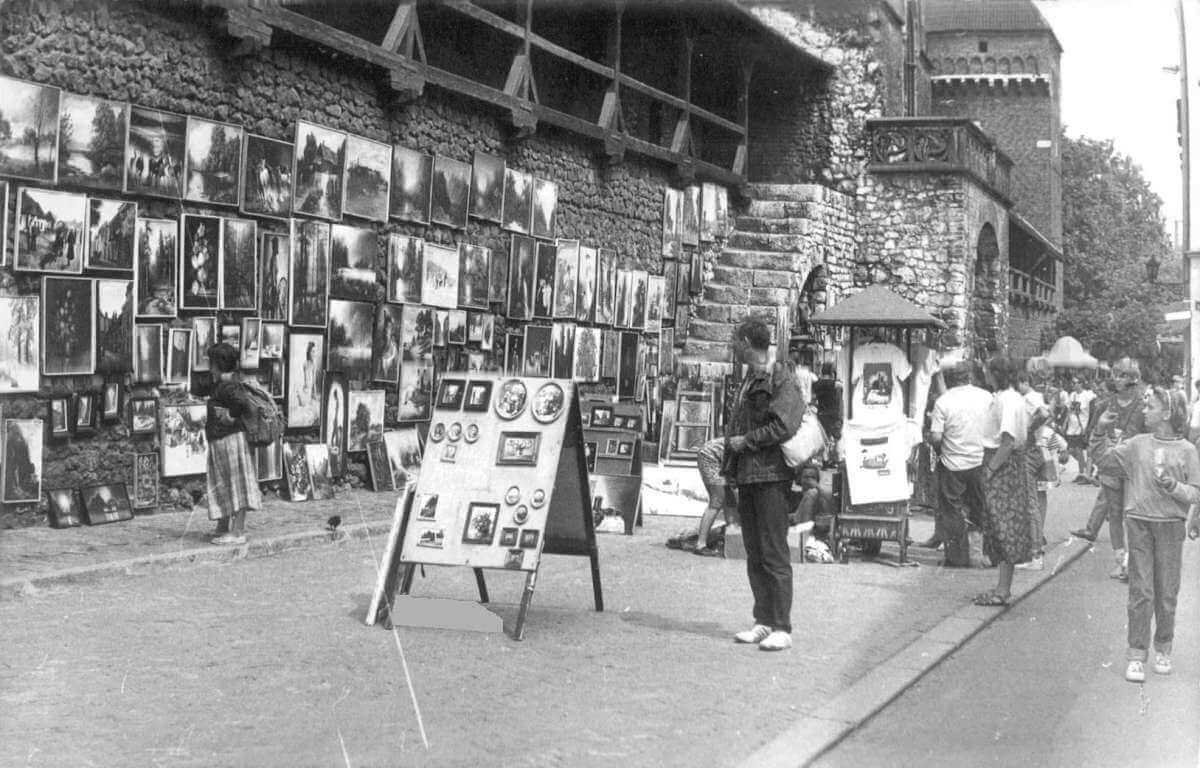

This Kraków knows, as do increasing numbers of tourist bureaus. In summer Kraków is filled with foreign buses, multi-lingual guided tours, and horse-drawn carriages giving wealthy Westerners a clattering, jostling quicktrip around town. The inner side of the town wall by Floriańska Gate is plastered with paintings, some imitation Old Masters, some Kraków cityscapes, some nude women, most of them tourist claptrap, all of them overpriced. Old Market Building is a warehouse of wood carvings, table cloths, chess sets, wall hangings, paintings and drawings, posters, books, pots, vases, T-shirts—the same kitsch you’ll find in Paris, Munich or Rome, names and styles superficially changed to reflect Poland. You need reservations days in advance for dinner at the Wierzynek—Kraków’s most elegant restaurant—or at the Kawiarnia Jama Machalika, a turn-of-the-century haunt for Krakówian theater types, now decorated in the main and entrance halls with cartoons, drawings, paintings, caricatures, costumes, puppets, and other theater memorabilia from that period. (More recently, the parking lot of the café was the scene of a genuine crime of passion, famous and jealous French singer rubbing out his wife’s Polish lover). On a winter evening, you can enjoy a delicious ice cream and hot tea on these plush red and black sofas and chair, but during high season you will have to fight off crowds of package tourists aggressively having the time of their lives, for which they worked so hard and saved so long.

You may even have trouble finding an empty table at the Balaton, a fine Hungarian restaurant on ulica Grodzka, identified by its sign of seven black frying pans, by the wine cask and goulash pot in the window, by the red and black tables below the low plastered vaults of the ceiling within. Or in getting tickets for the satirical theater Maszkaron, located in the basement of what used to be Old Town Hall, only a tower of which remains. Or, for that matter, just getting a drink at the Café/Bar Maszkaron during daytime hours, or when no production is in progress.

Catch Kraków while you can… or in the winter, when things quiet down. You’ll think you’re in Paris in 1958.

Probably you’d have better luck along the side streets, like the Kawiarnia Literacka, number 7 ulica Kanonicza, with its low, gray vaulted cellar, plaster walls, stone-cased windows, wood tables, and beamed ceiling. (By the time you read this, the whole street may be a tangle of such pubs, cafés, and restaurants, no longer quiet, no longer mysterious, no longer out of the way. As I write, not a building in Old Kraków is not being renovated into some little shop for gold and silver, a currency exchange, a gift shop, a restaurant or a café. Catch Kraków while you can… or in the winter, when things quiet down. You’ll think you’re in Paris in 1958).

Still Kraków contains Old enough for everyone, plenty of Old that package tourists will miss in the day and a half allotted to this city.

You must visit the Cathedral of St. Mary, with its two asymmetric twin towers, one resembling the crown of Heaven’s Queen, gloomy Gothic interior still painted from base of nave piers to the top of its vaulted arches, and the famous altarpiece flush against the chancel wall, five enormous gold figures just behind the altar and three more carvings in each wing: gold flaming from all surfaces. There is the Jesuit church of St. Barbara’s, adjacent to St. Mary’s. There is old St. Peter’s and St. Paul’s, in the neoclassical style, with carvings of twelve apostles outside and restoration in progress inside. There is the old Norman church of St. Andrew the Apostle, renovated during the eighteenth century to mostly baroque, but still a fine Norman exterior, which sheltered some few Krakówians from the Tartar invasions of 1241 and 1259. There is the old Dominican basilica of the Holy Trinity, Gothic nave with blue ceiling, side altars in mostly nineteenth century neo-Gothic, step down six steps from the 1990 street level to 1400 street level (entering St. Mary’s, you step down three steps—we’re talking Old here in Kraków), marble floor, stone piers. There is old St. Anna’s, the University church, Poland’s best example of high baroque, erected between 1689 and 1705.

If you’re not keen on churches, take in the Old Market Building in the center of the town square, its low vaulted ceilings decorated with plaster city crests of famous Polish towns, Łódź included. Or walk the circumference of the old city wall, a wonderfully settling stroll for a couple in love or an individual in search of solitude. A wonderful idea too: the polluted, infected, stinking moat was filled with earth and planted into a tree-filled park which fully encircles the old town, dotted with dozens of ancient gates, each identified in a diagram on the reverse of Kraków city maps. One of life’s finer moments is a night walk by the Wisła, or across the park, with streetlights glimmering through leafy boughs, or a number 3 tram rattling along in the fog or drizzle.

Old may be found in city museums as well, the City Museum, the ecclesiastical treasure houses, the library of the Jagiellonian University, open 12:00 to 2:00 most afternoons, more than a library, a series of academic rooms and historical treasures dating to the late middle ages. Old may be found in the city wall barbican, in what remains of Jewish Kazimierz, contiguous with Old City. Old is to be found in ulica Kanoniczna down by the southern end of old Kraków, a winding road of ecclesiastical edifices, cardinal’s hats and bishop’s miters carved above each doorway, still quite deteriorated and eerily untrafficked. Walking this street is like walking into a post-war movie set: nothing except the rats in the rubble.

Walking this street is like walking into a post-war movie set: nothing except the rats in the rubble.

Old is the University auditorium, where in 1939 Nazi officials invited the entire Jagiellonian faculty to a scholarly convocation, then packed them off to Auschwitz—Jews and gentiles, Poles and foreigners.

Old is the statues on building corners—no replicas or restorations these.

Old is a random glance down some Krakówian back alley at an upper story balcony in half-timbered brick.

Old in this city is a cobblestone in the street, a brick in a wall.

Old is the trumpeter’s call played live each noon from one tower of St. Mary’s (broadcast from Kraków on Polish radio throughout the country), repeated four times from each side of the tower and broken always in mid-call, in memory of the trumpeter who took an arrow in the throat while sounding the alarm at one of the Tartar invasions.

The most important Krakówian Old is Wawel, a hill overlooking the Wisła, a complex of buildings surrounded by a walled fortification including Wawel Cathedral, the royal palace—thePolish royal palace, accept no pretenders—and the foundations of several other buildings, which trace in gray limestone rubble the outlines of what is no more. The royal palace is an opulent display of Polish royal wealth hidden or reclaimed from foreign invaders, including enormous tapestries containing hundreds of pounds of gold and silver thread, and recently mended cuts where Poland’s conquerors cut away chunks of tapestry to accommodate windows and doorways of Russian or German castles.

The Italian influence is obvious at Wawel, both inside and out: King Zygmunt had the palace redone between 1506 and 1531 by Florentines Francesco Fiorentino and Bartolomeo Berecci. Berecci’s next commission was a mausoleum for the King, a magnificent Renaissance structure attached to the right nave aisle of the Cathedral, covered with a dome of golden scales, which clever Poles painted green during the occupation, and less-than-clever Germans mistook for the copper-covered domes of the rest of the Cathedral. One of the more interesting features of the castle is an unfaced section of stone wall near the museum entrance, said to be a surface outlet for some great source of subterranean power—magmatic, electromagnetic, psychic, or just plain superstitious—into which tourists can plug by backing their bodies against the wall for a cosmic recharge.

Wawel Cathedral is a sensory overload of Gothic and Renaissance abundance, touristed enough to necessitate “Direction of Visit” signs during the high season, but a true architectural monument to the Glory That Was Poland: marble, stone, brick, silver, gold over gold, oriental carpets and inlaid floors, Flemish tapestries on the walls, wrought iron gates of incredible delicacy, columns with golden capitals and marble bases, sculptured saints and bishops in flowing robes, silver and crystal reliquaries, angels and cherubs, lambs and skulls, relics and national treasures. The church building itself was consecrated in 1364, the third building to stand on this site. It is Gothic in shape and design, piers of solid stone, gray unpainted stone roof supported by a simple system of arches, some brick work in the nave walls. Fifty years after completion, it was surrounded by other Gothic chapels, all subsequently replaced or razed. Most of the interior is now baroque, including the shrine-mausoleum of St. Stanislas, a marble altar and a silver coffin, made in Gdańsk by Piotr von der Rennen. This tomb was designed by Giovanni Trevano; the tomb of King Ladislas Jagiełło, ornate marble carved a hundred years after his death, was designed by Giovanni Cinci of Siena. Around the outside aisles of the nave, a series of Renaissance and baroque chapels filled with carved marble of every imaginable color, none matching the richness of the Sigismund Chapel, but some coming very close, since most were built, like many other chapels all over Poland, in imitation of the Sigismund Chapel. Some—like Bishop Tomicki’s chapel in Wawel Cathedral—were designed by Tuscan architects who worked on the Sigismund Chapel. In all this wealth, the tombs of Casimir the Great and the crucifix of Queen Jadwiga are nearly lost. And the glass cabinet containing her orb and scepter, an opulence of genuine Old.

My favorite Old in Kraków, and possibly my favorite Old in Poland, is the Collegium Maius of the Jagiellonian University, an ancient quadrangle of buildings at the corner of St. Ann’s and Jagiellonian Streets, just a block off the Great Market Square. One of Europe’s oldest universities, the Jagiellonian was founded by Casimir the Great in 1364. The buildings of Collegium Maius date to the 1490s, when a number of independent structures were conjoined around a courtyard containing a central well, with an ambulatory around the circumference of the square, atop which a second ambulatory—access provided by ancient stone steps—opens to rooms on the first, and main floor of the quadrangle buildings. Atop that, two stories up, a wooden roof, painted on the underside in a series of medallions with gold floral designs. Pillars supporting the lower ambulatory are, of course, hewn stone, decorated in a pattern of raised, interwoven lines. The ambulatory roof—floor of the second-level ambulatory—is gracefully arched vaults. The walls are brick, of course, but brick of slightly irregular shape and masonry, with a particularly hand-made and pleasing effect. Door and window casements are stone, and because the quadrangle buildings antedated the idea of the University, no two walls, no two doors, are exactly alike, although all are definitely mediaeval: short, square, heavy doors, and small, barred windows. Design on the iron grills protecting each window varies, as do the doors themselves, which tend to be iron-faced: a lattice of iron strips held in place with decorative nails, and behind those iron bands diamond-shaped sections of more iron, designs pounded into them with a nail or punch or hammer. The ambulatory, the eaves, the copper gutter and the dragon-shaped downspouts give off an Italian flavor, especially the second-story entrance to the college library.

Some of the facing on the brick wall along the second-story ambulatory is carved stone, and fragments of ancient artifacts have been strategically positioned around the courtyard perimeter: a bit of column here, an old cannon there, a heap of limestone facing stones somewhere else. In summer, the stone flowerpots are full of geraniums and petunias, and they are augmented by wood flower pots full of leafy foliage. Along the inside wall of the lower ambulatory, hand-painted watercolors, a mediaeval simplicity to them but probably the work of a more recent artist, depict the town and the University at sundry points in their histories: 1369, 1575, 1582, 1775 (an impressive panorama of a procession along St. Anne’s Street to the basilica of St. Anne), 1582. The paintings are in plain wooden frames and show watermarks. They just feel Old.

The well, of course, is dry, but in the wall below the library entrance, the stone head of a satyr spits drinking water into a seashell basin. In one corner of the fountain you will find a brown ceramic coffee cup. The Latin inscription on the fountain reminds visitors that hospitality is a cup of water given to a thirsty guest.

The paintings are in plain wooden frames and show watermarks. They just feel Old.

Even in mid-summer, when the Collegium Maius is part of most tours of Kraków, it radiates a serenity you can’t find in Notre Dame de Paris, Cologne Cathedral, Westminster or even Chartres. And here is a much more organic harmony: Collegium Maius is just Old Poland being old. The courtyard is still a functioning part of a functioning University. The phone rings occasionally in the porter’s office behind one stone-encased, grill-covered window at the corner of the lower ambulatory. University personnel pass under the colonnade on University errands.

The courtyard’s atmosphere is artificially enhanced by the Gregorian chant emanating from the gift shop, but the shop is tasteful, part of the mediaeval charm: low plastered vaulting ceiling painted in a woodland scene, with semi-clothed women in a garden setting below, a canopy of tree branches and leaves above, something out of Chaucer or Boccaccio. The shop will sell you tapes of Gregorian Chant, plaster busts of Casimir the Great, chess sets, book plates and books to put them in, slides of the Jagiellonian treasures, some wall hangings, posters, nice art, and Jagiellonian University T-shirts and sweatshirts, university motto in Latin. Who’s to complain about canned music in this 100% class act? Besides, this place is most attractive when the gift shop is closed and the music is silent and the tourists gone home. When, on a slightly chilly afternoon in late autumn, you have time to sit with the bricks and stones that have seen nearly half a millennium of priests, potentates, rectors and professors come and go… to meditate on things past and passing… to plug yourself into that great power source up there in the library: parchments and codices and missals and atlases and encyclopedia, Copernicus’s own works revised in Copernicus’s own hand, treatises and histories and polemics and diatribes… to imagine yourself one in that long line of students and scholars, and, thus, part of the grand continuum of Man Thinking.

***

It’s the sixth chapter of the book by David R. Pichaske. Visit our website next week to read the next part of this extraordinary journey to Poland between 1989 and 1991.

***

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)