On Tuesday, June 5th, 2018, a group of students and professors from University of Warsaw entered the Kazimierz Palace, the official office of the university’s rector. The Palace, a proud relic of Warsaw’s neoclassical architecture and the heart of the university’s main campus in historic Old Town, has been occupied for 8 consecutive days and nights by about 20 representatives of the Academic Protesting Committee, an organization formed by members of the academic community opposing the new higher education bill. The bill is to be voted on in the Polish Parliament at the end of this week. The protest has spread to other cities in the country (Łódź, Białystok Gdańsk, Kraków), and academic communities put together a list of 11 demands they want to see implemented in the higher education system.

Self-governance – our weapon!

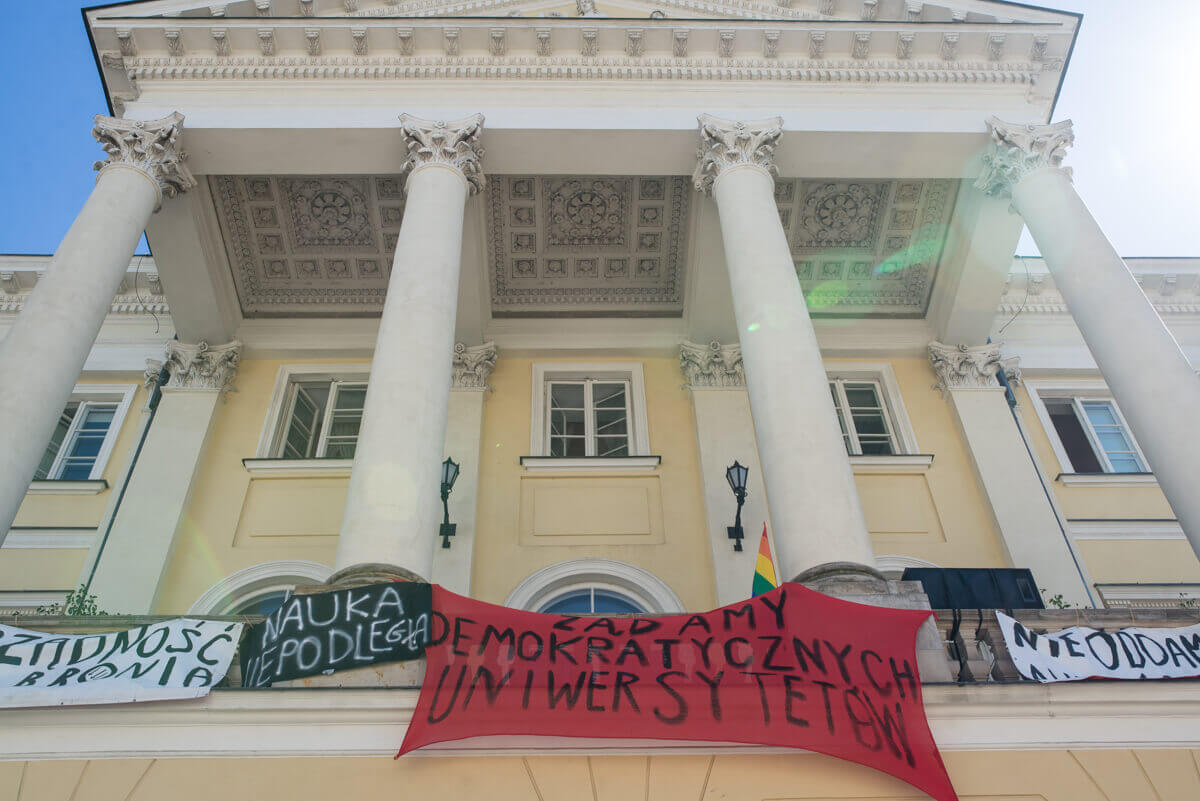

Since last Tuesday white and red banners with slogans: “Self-governance is our weapon,” “We demand democratic universities,” “We won’t give up our autonomy,” and “Sovereign academia” cover the monumental balcony of the palace. The new bill, also known as “Bill 2.0” (the origin of that name remains a mystery) or “Constitution for Education,” aims to introduce “university councils,” governing bodies that would consist of people not affiliated with the university. These councils would have the power to choose universities’ presidents. The protesters fear that with the new bill, the Ministry of Science and Higher Education will gain too much political control over academia, being able to directly influence the content of the teaching programs at the universities.

“These university councils are formations trying to mimic solutions employed in American higher education,” says Michał Wojcieszczuk, a resident of Warsaw who came to support the protesters on main campus last Thursday. “But in the US, where universities often have their private sponsors, it makes sense, while in Poland the universities are public.” “Proposed changes strip the academic community of influence on what happens at the university,” adds Dr. Agnieszka Dzikowska from the Faculty of Biology at the University of Warsaw.

Unequal opportunities in research

For Dr. Agnieszka Dzikowska, protesting against the new bill has a strong personal dimension. The latest available version of the “2.0” reform stipulates that women researchers employed at academic institutions end their research careers at the age of 60, five years earlier than their male colleagues. “The initial drafts of the bill provided for the retirement of both men and women at the age of 65. The most recent version of the bill requires women to retire at 60, which is a huge misunderstanding. Women have children, can go on maternity leave, and end up receiving their postdoctoral degrees later. Early retirement just when they start gaining impetus in their academic careers means taking away their opportunities for research.”

Furthermore, the reform proposes that regional universities in smaller cities lose their research budget and rights to confer PhD titles, effectively becoming teaching-only facilities. According to the Academic Protesting Committee, these changes jeopardize opportunities of students and academics outside of big cities, further supporting the interests of the urban elites.

“I believe that these smaller academic institutions are extraordinarily important for the local communities,” says Dzikowska. “If you want to promote and improve the quality of research at large universities, you need to subsidize them additionally, but not at the cost of the regional institutions.” One of the 11 demands put together by the protesters is to increase public spending on tertiary education.

“Kraków, Łódź – we are with you!”

Within a week, the protest spread out to higher education institutions in other parts of the country, initiating public discussions about the reform and the future of academia in Poland. A banner with names of other Polish cities (Białystok, Łódź, Rzeszów, Kraków, Radom, Wrocław, Toruń, Poznań, Gdańsk) where academics started the protests appeared on the balcony of the Kazimierz Palace. “We are fighting for a common cause,” says Michał Goworowski, a first-year history student who spent a couple nights in a sleeping bag on a carpet in the Rector’s palace. “We remain in touch with them,” he adds. A number of academic institutions, faculties, organizations, and trade unions issued letters of support for the protest, often explaining why the “2.0” bill will be detrimental to their work as scholars and pedagogues.

University – a common good

Academics who initiated the protest at Warsaw University, aside from physical occupation of the president’s palace, invite everyone to join community-wide debates and lectures. So far, students and academics had a chance to participate in a panel discussing the role and situation of women in the academia, learn about the history of student movements, or take part in collective readings of Derrida’s and Jaspers’ essays on university. Andrzej Leder, a philosophy professor at the Polish Academy of Sciences, in a lecture given in front of the palace last week alluded to the protests at Polish universities in 1981 and emphasized the importance of socially-conscious and democratically engaged academic community. Some instructors run their classes on the grass in front of the occupied building. Students hang around the sunbeds in front of the palace, mingling with professors and bonding with the colleagues from other faculties.

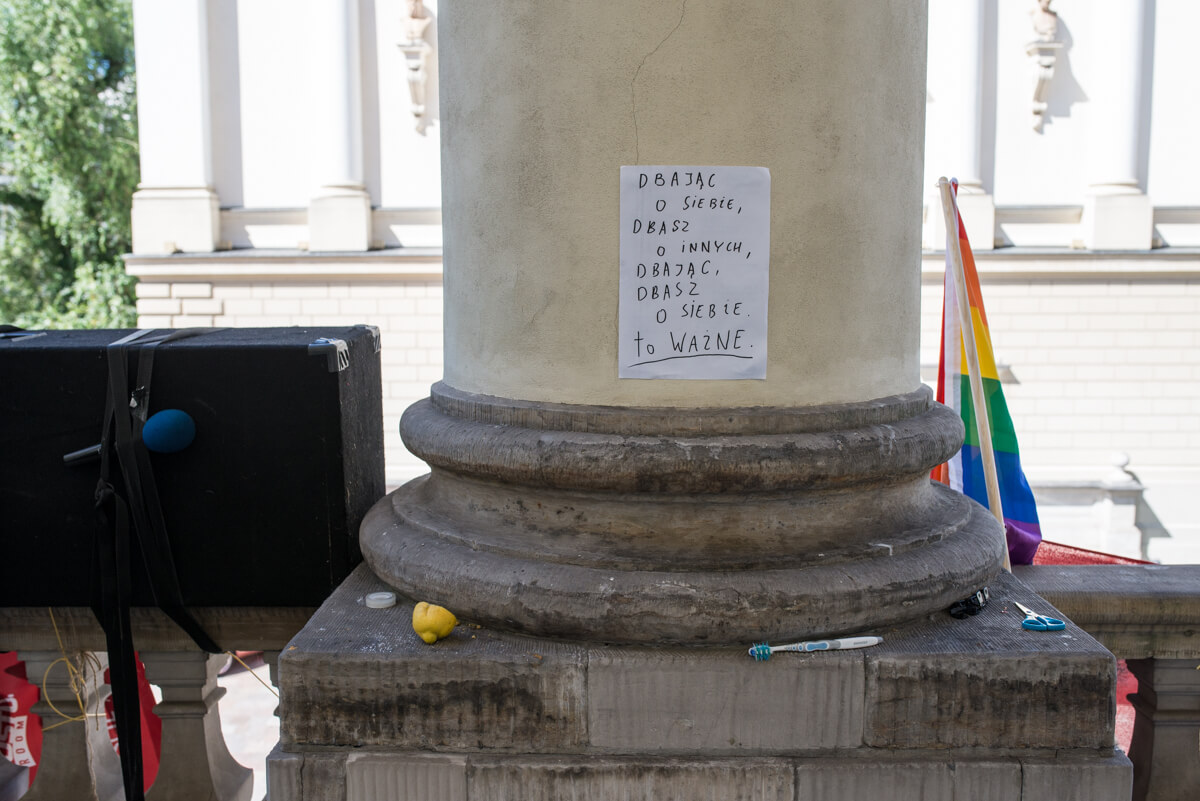

“This is our space,” says Goworowski. “It’s a common space and we want everyone to be able to come, ask questions, talk to us,” he continues. “Everyone has the right to come here, sleep here. We are trying to be as inclusive as possible.”

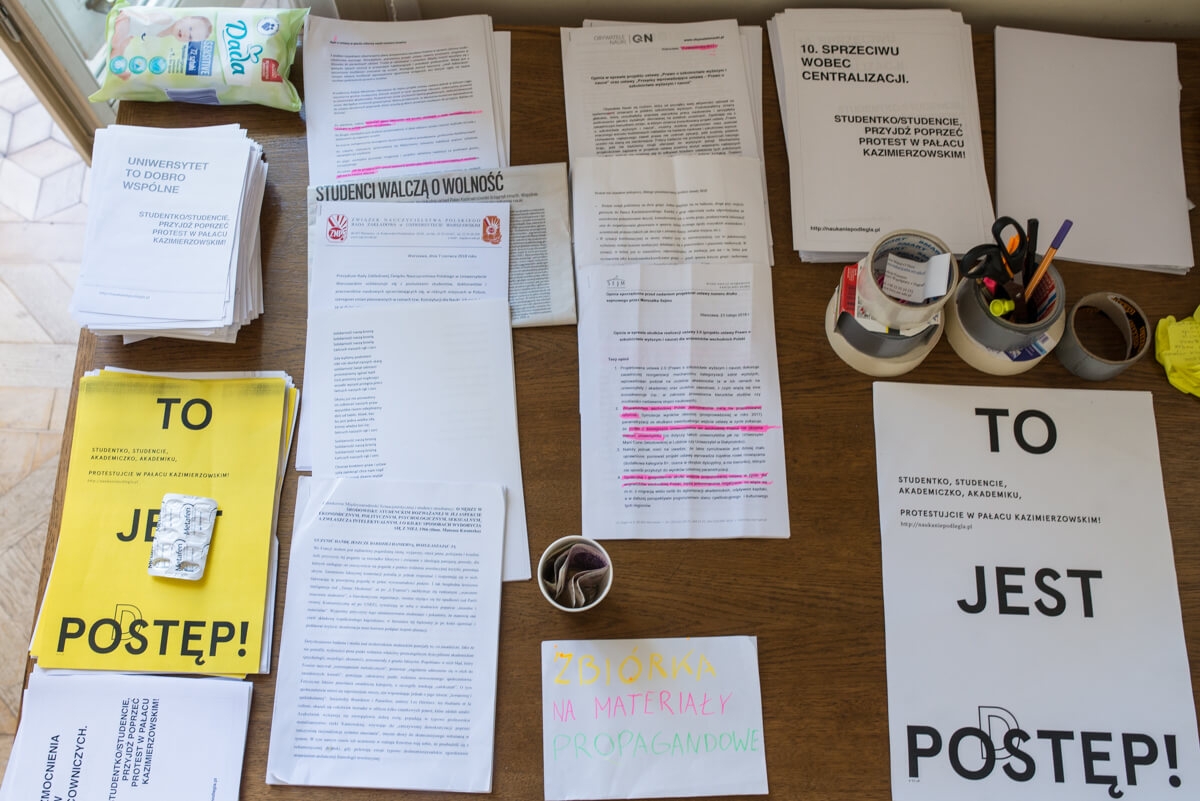

Inside the palace, the protesters have spontaneously put together a small library, which includes a selection of writings by Foucault, Butler, Brecht, Deleuze, Gorki, and many more. Additionally, a political science textbook about small European countries, a Vladimir Putin biography, and University as a Common Good by professor Krystian Szadkowski. The semester is about to end, so many students bring their books and try to study for their finals while they hang around the occupied palace. A weekend event “Silent protest. We are studying for exams” was announced on the Academic Protesting Committee Facebook page last Friday.

Controversies on all sides of the barricades

The new reform is pushed by Jarosław Gowin, former Minister of Justice in the government of the Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, PO), party leader and founder of conservative Poland Together (Polska Razem, PR) and Minister of Science and Higher Education in the government of Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS). Mr. Gowin refused to speak with the protesting students and called their protest “a youth happening.” “Bill 2.0.” has provoked a lot of controversy even among the politicians on the same side of the barricades. While some deputies of the ruling Law and Justice party, including its leader Mr. Kaczyński, support Mr. Gowin, others have voiced their concerns about his project. One day after the student protest started, Krystyna Pawłowicz, a law professor and conservative PiS politician known for her homophobic views tweeted that she will vote against the new bill. Robert Biedroń – the first openly gay member of the Polish parliament and mayor of Słupsk, congratulated the protesters on his Twitter. Joanna Scheuring-Wielgus, an independent MP, who has recently given up her membership in the Modern (Nowoczesna, N), a liberal and pro-European party, called for help in collecting food, hot tea, and sleeping bags for the protesters on her facebook and twitter pages.

Those in support of the new bill, on the other hand, argue that the bill will raise the quality of teaching and research at Polish universities. “The bill will create a new model in higher education,” says Mr. Gowin. “It gained support of the Student Parliament, an organization that represents interests of 1.5 mln of students in the country.”

Mr. Gowin himself discredits the protesters’ concern that the new bill strips academic institutions of their autonomy. He states that he has sought advice and contribution from all sorts of communities in creating the “2.0” bill. Michał Goworowski, one of the student protesters, believes that Mr. Gowin’s statements about the consultation period are hypocritical. “The consultation period that Mr Gowin talks about was not inclusive,” says Goworowski. “Mr. Gowin is being extremely arrogant.”

Political Context

According to Michał Wojcieszczuk, “Bill 2.0.” fits into a larger political trend of what is happening in the country. He believes that the higher education reform will become “a tool to enforce political interests of the ruling party in the academia.” “We cannot ignore what our reality looks like,” he continues. “We have a prime minister who kicks out Barbara Engelking from the International Auschwitz Council [Engelking is a prominent Holocaust historian whose presidency on the International Auschwitz Council was not extended by PM Morawiecki.], we have a Minister of Culture who cuts funding for the Holocaust Studies journal, and many other examples proving that our politicians itch to influence research and academia.”

Higher education needs reform

At the same time, the protesters believe that tertiary education in Poland requires a solid reform. “There is a lot to change [in the higher education system]. Status quo is absolutely unacceptable. There are a lot of problems, for example, inaccessible student accommodation or the problem of socioeconomic exclusion,” says Goworowski. “There are some positive elements of this new bill, such as increasing access to benefits, funding, financial assistance. The bill includes some good ideas but it’s a shame it is written in such an authoritarian spirit,” he concludes.

“When you carefully listen to what the students and academics say…it is not that they are against a higher education reform. It is a case similar to the one with the courts. They wanted a reform, but they didn’t want a government official to come and tell them that they will decide about everything from now on,” says Wojcieszczuk, who came to stand by the students on a Thursday afternoon.

University – a social space

The new bill is supposed to be voted on in the parliament in the end of the week. Meanwhile, students and academics plan country-wide protests against the “2.0” bill on Wednesday, June 13th. Meanwhile, Piotr Mueller, the Deputy Minister of Science and Higher Education, declared that there are plans to introduce 50 corrections to the current version of the “2.0” bill. Mueller denies that these corrections have anything to do with the protests taking place at major Polish universities. Members of the Academic Protesting Committee remain skeptical of Mueller’s declarations and invited Mr. Gowin to direct talks over the future of Polish higher education. “We are working, are you?” the protesters ask the ministers on twitter in the middle of the night.

Michał Goworowski believes that the meaning of the protests goes beyond politics. “Occupation of university space is a new form of a protest, transforming the rector’s palace into a social space,” he says. Dr. Helena Patzer, an anthropologist at the Institute of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Warsaw, could probably agree with her younger colleague. “In our world everyone is busy, always running around. Essays, exams, administrative work… This protest creates a space to meet people, get to know each other and our respective disciplines better,” she says. “Professors run their classes here, sitting on the grass. This is a moment for all of us to form all sorts of alliances and plan activities together, not just protest against the new reform.”

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)