When it comes to souvenirs, I am more eccentric than most Americans: I go directly for the workaday, the off-beat, and, usually, the cheap. No cuckoo clocks from Bavaria, no overpriced Hummel figurines, no coffee table picture books on The Royal Wedding. From a two-week stay in Great Britain a couple of years ago, I brought home only a wooden fish crate, used by Scottish fishermen to ship the day’s catch from Tarbert, Scotland to Liverpool, Manchester, and London. “James MacFarland and Sons, Ltd.” is stenciled in black letters across each end. I fished the thing from debris in the Tarbert harbor below the bed-and-breakfast place in which I was staying, and you should have seen the people at Pan Am when I checked it as a piece of luggage headed for Minneapolis-St. Paul airport. From Rome I once brought a small red brick, a bit of the old Roman Forum; from Paris a piece of Notre Dame (a weathered ornament that had been removed from the cathedral for replication and replacement; I did not chip it off the building proper, although I did liberate it, using a long stick, from behind a protective fence); from the coastlines of Europe and America I have collected an assortment of rocks and shells and even, from Greece, a bit of wood from an old Greek fishing boat, weathered and painted that lovely Grecian blue.

So what will return with me this summer 1991 from Mother Poland?

T-shirt or sweatshirt with some Polish writing on it.

Contrary to what you might imagine, souvenirs of Poland are not hard to come by, even in Łódź, by no stretch of the imagination a tourist city. The country—and this city—is full of tourist claptrap, although at this writing I have yet to find the one typically tourist thing I really want, namely, a T-shirt or sweatshirt with some Polish writing on it. Some tourist junk is junkier than others, but visitors have options: amber and silver jewelry, most of it from the Baltic coast; hand-knit sweaters in gray and red designs from the mountains in the south; crystal Polish and Czech, clear and colored, some carefully etched with hunting or fishing scenes which no two pieces duplicate exactly; little dolls in the peasant costumes, which nobody in Poland wears any more, except in Łowicz on All Saints Day. Cepelia stores sell hand-embroidered peasant costumes for living dolls small or large, and tablecloths, and woven wall hangings (quite popular with Poles, although they have risen in price so much that I don’t know anyone who can afford them). Cepelia stores also stock carved wood mugs and boxes, cards and paper cuttings, and wood carvings, including Polish peasants, Jewish fiddlers, and chess sets great and small, painted and unpainted. I appreciate Polish wood carving for its peasant vitality, something that long ago disappeared from the more professional—and more mechanical—productions of southern Bavaria.

Little dolls in the peasant costumes, which nobody in Poland wears any more.

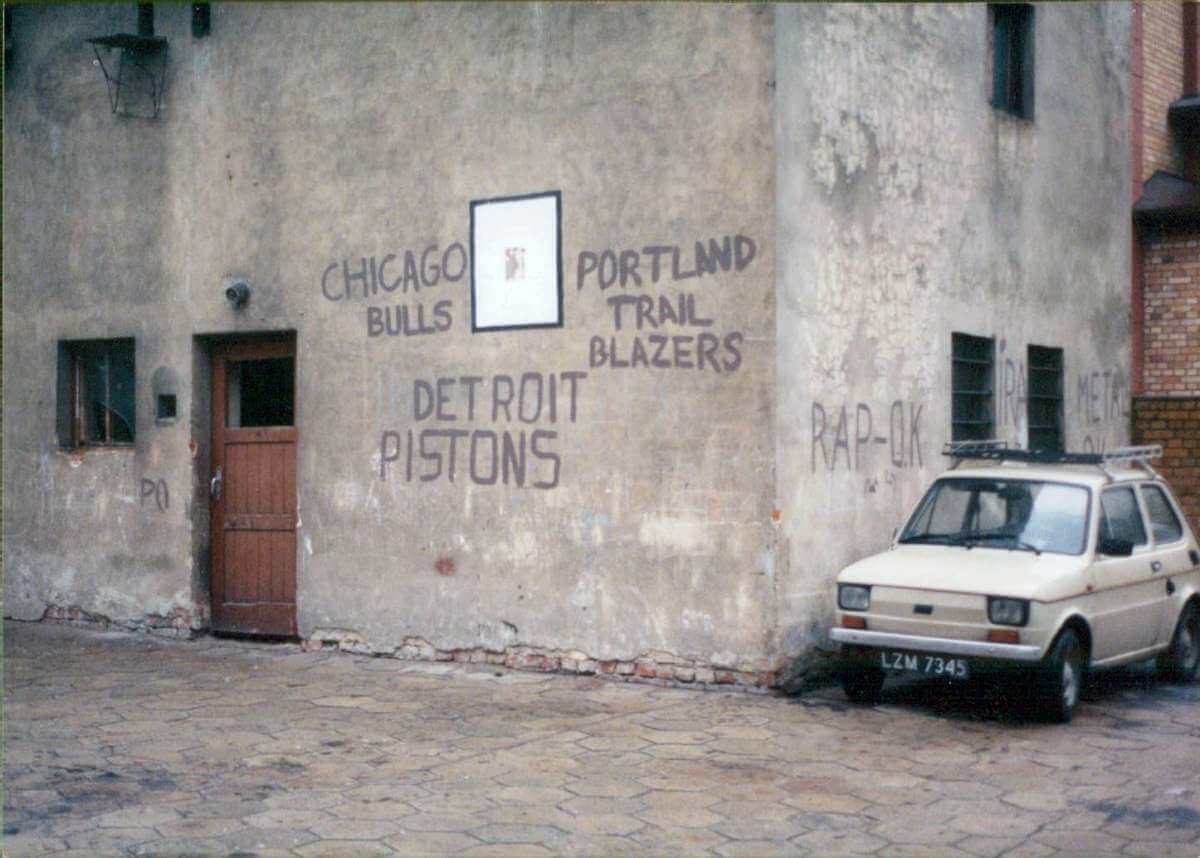

In major tourist cities like Gdańsk, Toruń, Kraków, Warsaw and Poznań, artists hawk watercolors, etchings, and even original oil paintings of local scenic attractions—exactly what my father brought home from his trip to Germany in 1952, exactly what my Aunt Esther brought back from her trips to Rome and Florence and Milan in the 1960s—at prices, comparable to what they paid then in those now-affluent countries. In local market squares you can also buy postcards and photographs from an army of pre-teen merchants who buzz like flies around all suspected Westerners. They all use the same hustle: one ten year old boy will sidle up beside you and ask, “Proszę, która godzina?” (“What time is it?”) If you tell him the time, in proper Polish, he is off in an instant with a simple thank you. Sometimes he’ll leave you alone if you show him your watch. But if you look puzzled, or answer in your clearest English, “I’m sorry, I don’t understand, kid, I’m from Minnesota,” he will call in the troops: “Marek! Krzysztof! Piotr! Chodzi tu!” Each kid has a deck of postcards, a map of the city or a booklet about the cathedral…each costing one dollar.

Religious shops sell wood-and-pewter reproductions of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa, wood carvings of the scorned and scourged Christ, and all manner of Pope paraphernalia: cards, calendars, pennants even aluminum foil helium-filled balloons. In the bookstores, several options: Polish translations of English classics like Dr. No and Cooper’s The Prairie; selected volumes of the 18-volume piano scores of Chopin, edited by Paderewski, the less popular volumes at maybe 500 złotych, the more popular (and more recently restocked) volumes at 25,000 złotych, or, shock of shocks, the études, back in stock only this month, at 80,000 złotych, or nearly eight bucks. There are lovely coffee table art books, gorgeous four-color printing on thick coated stock, weighing several pounds each, printed in Warsaw or Leningrad (often in Russian—although English and Polish texts can also be found) and therefore usually full of paintings from the Hermitage Museum, at ridiculously low prices: a few dollars for 250 pages of “French Impressionist Paintings,” 450 pages of “Soviet Folk Art,” or 350 pages of Pablo Picasso. In bookstores you will also find horse calendars, art calendars, and those Polish girlie calendars that hang in offices all over this Catholic country, including offices staffed only by women, including the office of the Institute of English Philology, whose director, assistant, and entire secretarial staff is female.

Everyone takes at least one photo of the NO PHOTOGRAPHS ALLOWED signs.

You may also find comic books—Kaczor Donald and Myszka Mickey are popular—a few nicely illustrated children’s books, and more postcards and maps. And cute little stickers, probably Disney characters or Smurfs or television-promoted junk. There is even, in the philately shops, a series of Disney character stamps.

Finally there are photographs: everything you are permitted to shoot and many things you are not permitted to shoot (everyone, it seems, takes at least one photo of the NO PHOTOGRAPHS ALLOWED signs that mark railroad stations, military installations, and even utilities). Use East German Orwo film, and your photos are nearly free. Like everything else in the East, it’s a little grainy, not Kodak Gold Ultra 400 by a long shot, but why not make your photograph of Poland a true presentation of the landscape itself?

But we can be more imaginative than this. How about a book: Satysfakcja: Historia Zespołu The Rolling Stones? How about Ronald Reagan w Białym Domu, a gift for comrade Bill Holm, who so admires the ex-president? How about half a dozen Solidarność pins, T-shirts and even daybooks bought in Gdańsk at a table in St. Bridgid’s?

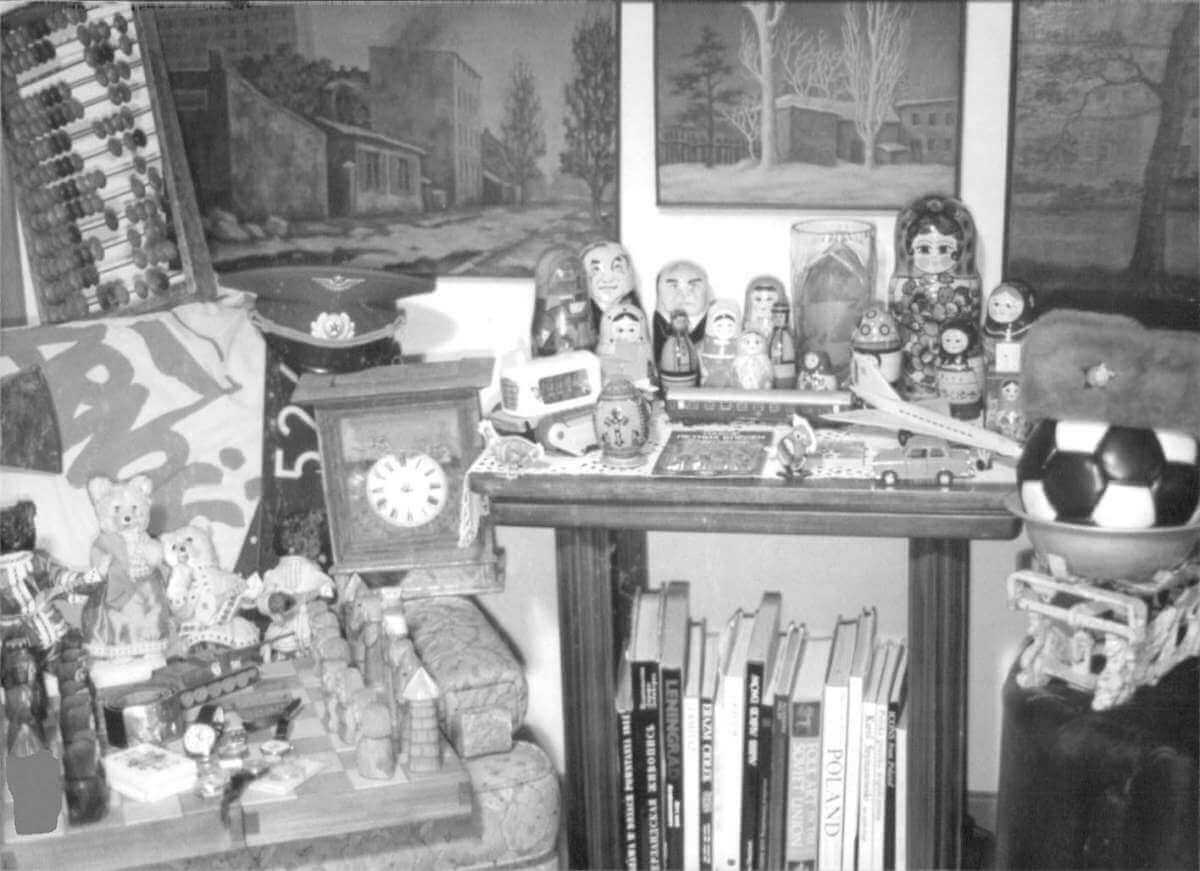

I have four wind-up Soviet bears in peasant costume, one yellow and female, the other three males playing balalaikas… Goldskilocks and the Three Bearskis. I have a set of children’s blocks in Polish, and a set of toy print shop letters, also with Polish alphabet characters. I have a Polish “monopoly” set. Michelle has bought a couple of HO scale model railroad cars, green and grey, PKP (Polskie Koleje Państwowe) painted on the side. I bought one elegantly carved and painted chess set in Poznań for $50, and one workaday set for a buck from a Russian in the street market. (If you want to play like Kasparov, you have to learn on a set like the one he learned on).

If you want to play like Kasparov, you have to learn on a set like the one he learned on.

Actually, I have collected quite a pile of Russian paraphernalia: a dozen or so matrioszka dolls, three or four silver and red enamel stars with the caption “Workers of the World Unite,” a medal or two that read “CCCP,” one of those heavy winter fur caps with flaps that fold down over the ears, several watches (“perestroika” designer watches for Michelle, who has a collection of over a dozen different designs, and for me either the gold-plated watches with date and time functions, or the heavy pseudo-Rolex models with the red star and CCCP logo). I have several children’s toys, including a socko battery-powered tractor with two speeds forward and reverse, and lights that flash red and yellow as the engine cylinders pump up and down.

I have a tin Żywiec beer tray bought from the proprietor of a mountain hostel last November for $1 (“That’s a lot of money,” Paweł Krakowian objected in astonishment at the time), and a “herbata” tea tin bought on the street for another dollar. I have one of those twig brooms used by Polish street workers. For Ron Koperski I saved the Christmas host, blessed by the Pope himself, and distributed at the beginning of Advent to each household in Łódź by a team of priests. I have Łódź boy scout patches bought at the camping store on Piotrkowska, and some hand-painted, hand-thrown dinner plates shipped to Poland from Vietnam, sold here in stores for 39 cents each. I have one place setting of Uniwersytet Łódzki silverware. (I bought six place settings of silverware for the apartment—fair trade, I’d say.)

I have, of course, the iron balance scales, and an aluminum cream can, and a cobblestone from the street on which I live. And I have six Jan Filipski oil paintings of old Bałuty, if I can get an export license and find a way to get them onto an airplane.

I have six Jan Filipski oil paintings of old Bałuty.

There are a dozen records of Polish folk music and jazz, and four Paul McCartney Live in Moscow albums, bought for $1 apiece in the music store on Piotrkowska, bringing, I’m told, $25 in New York.

If I can figure a way to get them onto an airplane, I have also one genuine wood, cloth, and leather rocking horse, two and a half feet high and three feet across at the rockers, its wooden head hand-painted and metal stirrups and real horse hair mane… and a child’s peddle car, Russian-made, three feet long by foot and a half wide, headlights that light, horn that goes “beep beep,” a heavy sheet metal toy which some kamikaze kid of five would have a ball pumping all over the house, and half a dozen Polish kamikaze kids eyed ruefully as I brought it home on the tram for Michelle’s Christmas present.

I have the case of an old cuckoo clock I bought at the weekend Superbazaar by Kaliska football stadium, its wood all eaten by worms, its face replaced with a scene, reverse painted on the glass, of some World War One soldiers riding to attack—to defend—one country or another on brown motorcycles.

I have a Coke bottle in Hungarian, a Pepsi bottle in Russian, and another Pepsi bottle in Polish.

There are several posters advertising various plays, concerts, elections, and art exhibits, including the “HollyŁódź” poster and the “Łódźstock” poster, which nobody back home is gonna get, because Americans don’t understand that in Polish “Łódź,” is pronounced not “Łódź,” but “Woodge.”

But the best souvenir to date, the most curious, the most preposterous, is the set of “Stainless Steel Tool for Miniature Trees and Rockery” made in the People’s Republic of China. The set contains seven tools, each with a steel head and wooden handle: rake, clippers, saws, spades. It resembles stainless steel about as much as the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayr lion resembles Goldilock’s ailing aunt, to borrow a phrase from Thurber, but the manufacturer was thoughtful enough to include a whetstone on which to sharpen cutting tools, and an explanation in Chinglish: “Our factory is the special manufacturer of the tourist’s gardening tools, which are the most ideal ones for daily gardening, and picking miniature trees and rockery when traveling. This product is made of stainless steel, cleverly designed, small and exquisite nice-looking and easy to be taken. Painted with scenery of famous spots on handle, it also has the unique local traditional style.”

This set of tools, with English explanation, was carefully packaged in hand-made wooden carrying case, with plastic leather handle, then shrink-packed in plastic and shipped from somewhere in the People’s Republic of China to Łódź, a textile-manufacturing city of 900,000 blue-collar workers in the very center of Poland, where it was bought for $1.45 by a visiting American professor without a miniature tree or rockery to his name.

Now isn’t that the funniest thing ever?

***

It’s the sixteenth chapter of the book by David R. Pichaske. Visit our website next week to read the next part of this extraordinary journey to Poland between 1989 and 1991.

***

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)