Often in our discussions and struggles in favour of democracy in an urban context, culture is not really taken into consideration as a relevant element of progressive agendas, social movements or political civic platforms. Therefore culture is often left behind in the processes of social transformations in our cities. This is a mistake. The right to culture is one of our fundamental rights and is equally important as the right to water or other commons. In order to fully include culture into progressive agendas of social movements and political civic platforms on a municipal level and beyond, we need to understand the way culture influences the wellbeing of citizens and we need to construct conditions for the right to culture to be exercised without limitations in the urban surroundings. I want to share the viewpoint of an activist involved in struggles for free, equal and democratic culture that could inspire activists in other areas to look at culture as an ally in our common fight for a better future.

Culture Doesn’t Mean Art

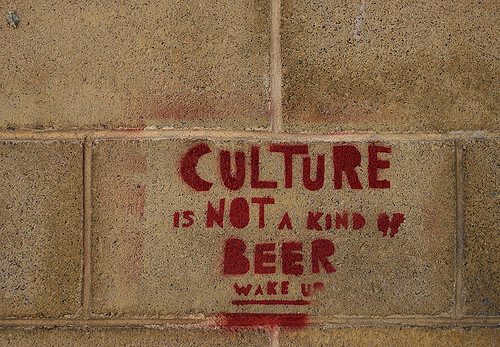

What exactly are we talking about when we say we want to tackle issues of culture in the urban environment and the influence of culture on the quality of life of citizens in urban areas? First of all, when we say “culture” we do not mean artistic production. We aren’t talking about theatre performances or art installations displayed in museums. At least not at the forefront.

Culture is often left behind in the processes of social transformations in our cities. This is a mistake.

The questions we are asking also do not relate to public cultural and artistic institutions. We don’t ask ourselves how to increase audience attendance to opera houses or art galleries run by the state or municipal authorities. These are not the most relevant questions, which should be raised when thinking about culture and its influence on the urban environment. In Poland, where I live, over 60 percent of the population neither experiences nor exercises culture through public cultural and artistic institutions.

When we say “culture”, we also do not refer to cultural industries and the position of the creative classes in the social compositions of the cities we live in. Our question is not how to introduce conditions for the advertisement, film and television industries or entertainment and design industries so they can smoothly commercialize their creative resources and increase a city’s GDP. We know very well that the influence of creative industries on the urban space is undeniable. More than half of the culture in Warsaw, the capital of Poland, is being delivered by creative industries. More than half of the cultural production therefore is directly related to a commercial approach towards culture and recognises citizens as customers of cultural products.

Neither cultural industries nor public institutions should be put in a centre of a discussion when reflecting on potentialities of culture to transform living conditions for inhabitants in our cities and on exercising their right to culture.

Culture is a Foundation

First of all, culture is the way in which we express ourselves, communicate between each other and how we translate our realities into common symbols and values. It is about how we practice our individualities and transform them into mutual relationships built within the communities we operate in. It is about how we practice community identities and individual existential, political and esthetical approaches. Culture also expresses social differences in the urban space, which are born out of a variety of class, race, religious or gender backgrounds. It is a territory of negotiating them or finding antagonistic ways of overcoming the contradictions that they produce. Those are the foundations on which artistic production is being constructed and can therefore vocalise itself through public institutions or the creative industries’ tools.

So, when we ask about culture in the urban environment, we first of all ask how to empower the citizens’ capacities of self-expression, mutual communication, creation of community bonds, negotiation of values and overcoming the contradictions of antagonistic social universalities. When we ask about the right to culture, we first of all relate this to the right of the people to create their own cultures the way they want and secondly to the right to have access to culture in its public or commercial dimensions. In such a case, in todays’ cities, the right to culture is most often restricted or even violated although we might not recognise this fact.

The Right to Culture is Permanently Violated

In order to be more specific, let me give you three simple examples. They show how self-expression – which is the essence of exercising the right to culture – is being abused or even penalised in reality. I’ll begin with an obvious instance beyond the urban space to tackle the issue preciously and afterwards, I’ll move towards two cases related directly to a city’s environment.

Let’s start with copyright issues. Copyrighting, which, by the way had been born together with the birth of cultural industries, to block peoples’ expressions due to limitations of usage and sharing cultural contents through internet networks. The problem here is not even an opposition between “open” and “closed” visions of culture. It is about violating the fundamental right to culture.

Let’s move towards the city space and take a look at the juridical approach towards graffiti. In this case, self-expression is very often regarded as vandalism and is ruthlessly penalised. Putting restrictions against different ways of self-expression is an abuse of the right to culture. Penalising graffiti, which is one of the most accessible tools of urban self-expression, mirrors a juridical attitude towards people’s creativity. It’s valid as long as it is legitimised by the political authorities or professional artistic circles. Otherwise it’s not culture but vandalism.

A more thought-provoking example could relate to the regulation of the ways in which public spaces in our districts or neighbourhoods are being expanded. Even in their closest environments, people are often not allowed to organize their surroundings by themselves in a way they find appealing or in a way that would meet their expectations related to their class, race, gender or religious backgrounds. Public spaces are being organised by urban planners, design and architecture experts. It is not only ineffective from a point of view of increasing the quality of life in urban areas, but it is also an example of structural resistance of the political and economic system we are living in, against the citizens’ right to culture. I don’t think many of us would say that urban planning could be an instrument of violating this fundamental right, but if we understand that this right as the right for citizens’ self-expression and of transformation of their surrounding by themselves in a way they want, then yes, urban planning is becoming a tool to limit the right to culture as well as copyrighting or the penalisation of graffiti.

Culture and the City

In order to allow culture to influence a city space in a positive manner and to act in favour for the citizens’ wellbeing, what is needed is to create conditions for people to use their expressive and creative capacities to transform the urban environment in the way they want, with the tools they recognise as efficient and legitimate. It demands an understanding as to precisely how people express themselves, how they create social and community bonds, how they negotiate values and what kind of particular political, juridical, economic and social barriers stop citizens’ cultural practices from growing and developing. After we are able to understand that, we can fight for the dismantling of those barriers.

Culture is a common. We cannot allow it to be captured by capital and be monetised, as well as we cannot not allow it to become a tool of the governments to form our societies according to their ideological patterns.

If so, it raises a question: what place do creative industries and public institutions have in such a landscape of peoples’ cultural activities? We need to be more strict and demanding towards private and public terrains. Creative industries in the recent decades have become an instrument of anti-social and anti-democratic transformations of city spaces. They have deprived the popular and working class of the space to develop their cultural capacities, thereby affecting the growth of inequality in urban areas. They have also deprived citizens of their right to the city handing public spaces to corporative entities, commercializing common urban territories and transforming them in a way they could benefit the rich. It is time to invent tools of reducing the influence of cultural industries on our cities and to regulate the hegemony of the creative class in the districts and neighbourhoods, which are gentrified by the creative industries.

Public institutions, on the other hand, should be transformed according to the citizens’ dynamics. There should be much more control given to the people and it should be co-managed by communities. They should also endeavor to mirror people’s expectations towards artistic and cultural articulations. We need to struggle against the alienation of artistic production, which is being vocalised in public institutions, by reformulating the notion of art towards the notion of culture and artistic production towards cultural productivity and the notion of artist towards the creative citizen.

***

Culture is a common. We cannot allow it to be captured by capital and be monetised, as well as we cannot not allow it to become a tool of the governments to form our societies according to their ideological patterns. Our cities became a battlefield for struggles in favour of democracy and social wellbeing. How could we support culture in not being left behind in those struggles? Let’s do what we would have done with all other commons. Let’s give culture back to the people.

***

This text is a re-worked version of a speech delivered within Co-creating the City pillar of United Cities and Local Governments summit on October 14th 2016 in Bogotá. The author would like to thank Bernardo Gutiérrez for his kind invitation to contribute to the congress and all the participants of the Right to the Diverse City session for their inputs in a discussion.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)