One of the core themes for discussion in the Fearless Cities summit in Barcelona few weeks ago was the feminisation of politics. What it means to feminise politics has been largely written and discussed in Spain the past couple of years: when we speak about politics we mean any physical and symbolic structure where a group of people comes together to reflect, demand and act towards a common socio-political, cultural or economic objective. The debate, which is still developing, has some axes that can help us understand the difficulties of feminising politics without first transforming the political institutions and movements themselves from the inside through daily feminist actions in both public and domestic spaces.

It is not enough to reclaim more representation in institutions, we also need to reflect about the structural conditions of society that leave us underrepresented.

Political institutions are aware that the role that women are playing cannot be ignored, and because of that there is a general tendency in social and political contexts to push for at least a discussion about feminism and the feminisation of politics. In the past years we have seen women taking more and more significant positions in roles of representation and in decision-making processes. We have seen more women appearing publicly on behalf of some parties or movements, and we have seen an important intention, with or without success, of having a 50/50 representation of men and women in panels of discussion, social movements and even governments.

Even if this is a fundamental condition and first attempt at the process of feminising politics, it seems clear that there is a significant difference between the number of women that have a role of representation in political space and the power of decision and action that these women have de facto. The level in which women involve and participate in political debates connects with our historical underrepresentation in the public spaces. Feminism has taught us that it is not enough to reclaim more representation in institutions, we also need to reflect about the structural conditions of society that leave us underrepresented. That is why it is not enough to include more women in the structures that are excluding us “by nature.” We need to think instead about why and how they are doing it. Women need to be more represented but we also need to change the structure of institutions that from nature expels us.

Women are denied authority and legitimacy as autonomous subjects and are treated as a permanent minority.

Political Critique spoke to sociologist Kateřina Cidlinská about the unequal conditions for women in academia, a public space that women still need to fully conquer. We asked Kateřina, who is also the coordinator of a mentoring initiative for early career researchers at the Czech National Contact Center for Gender and Science, why it is so difficult for women to achieve leading positions in their fields, and what structural and subjective problems are in their way. Cidlinská explained that many women socially internalise messages and comments about their lack of qualification. We feel the need to apologise more to their colleagues and additionally tend to attribute their successes or high positions in companies or public charges to external factors such as luck, the way we look or help from others. Women’s qualifications are therefore puts in doubt through stereotypes that almost never apply to men. Women are denied authority and legitimacy as autonomous subjects and are treated as a permanent minority. It is precisely the fact that women have been excluded for centuries from the centers of power and political decisions that we need to be given the opportunity and space to reclaim their right to be in politics and the space to exercise it.

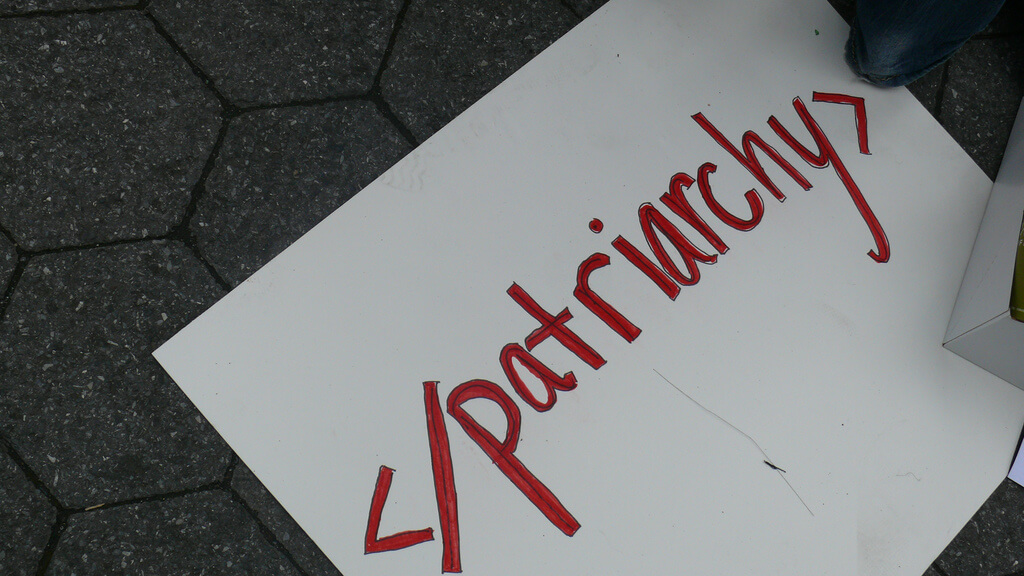

Achieving parity, meaning achieving an equal presence of women in the spaces where decisions are taken, is necessary and has major consequences in political dynamics. Some political actors and institutions, starting from Donald Trump – but not only, are taking the advantage of having women in positions of visibility and responsibility to keep “business as usual”, in fact, reinforcing patriarchal structures that seem to become justified by the mere presence of women. The mere presence of women gives visibility to a traditionally excluded actor in public life, in politics, and recognises the importance of the role of women accessing political power. Increasing the number of women represented in political spaces is fundamental but not enough if by feminising we understand something more than the mere physical presence of women in these spaces, if by feminising we intend a radical change of the dynamics in which we live and interact in the public political sphere, but also in private and domestic ones.

Political change must rethink capitalist growth which has been supported by unpaid domestic work and exercised traditionally by (mostly precarious) women

From a feminist viewpoint politics needs to follow a road that moves women out of the traditional social and political marginalisation. On the one hand, feminism is the legitimation of the increasingly active role of women in politics, and the response and patriarchal reactions against this shift. It needs to be used as structure and method and not as object or topic for discussion. This structure needs feminist references and emotional perspectives for the struggle of women and feminists demands. On the other hand, feminising politics also means bringing the responsibility for domestic care into the public sphere, with a double objective of demanding a shared responsibility in the tasks that historically have been assigned to women, and demanding a public debate that highlights the social responsibility of restructuring the domestic work, to avoid delegating it to women, and more specifically, to the most precarious women.

It is no coincidence that for the last century the feminist movement has raised the slogan of “what is personal is political”, expanding and disputing since then the sense of the political sphere. To give an example, in the 70s, the campaign on international wages for housework raised awareness of how housework and childcare set the base of industrial work and stake the claim that these are necessary tasks that should be paid as wage labor. This situation is exacerbated in a globalised world run by neoliberal policies that generate precarious work and increase the pressure of domestic care responsibilities on women. Political change must rethink capitalist growth which has been supported by unpaid domestic work and exercised traditionally by (mostly precarious) women, who as result of aggressive capitalism in the last decades have been forced to join the productive labor world while at the same time being linked to the domestic space in a way that is not true of men.

No progressive political movement, tentative of new party, or social institution will succeed today if it is not led by feminism and with women.

In order to maintain – and increase – the rights that women have been winning throughout history thanks to the feminist struggle, we need to be aware of what it means to be a woman in the public, the political, and the domestic spaces, and this begins by acknowledging that we belong to a different political status than men. Recognising this does not mean accepting it or surrendering, it does not mean that we resign to remaining in a different political class; it means being aware of the place from where we are struggling but at the same time gaining public spaces. No progressive political movement, tentative of new party, or social institution will succeed today if it is not led by feminism and with women. And this will not happen if we do not reconcile the public and political with the private and domestic.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)