Markéta Vinkelhoferová: For nearly three decades you have been working with waste pickers to claim their rights. How did you get your job?

Lakshmi Narayanan: In 1989, after finishing my masters in social work in Mumbai, I came back to my hometown Pune, in Maharashtra state, where there was a job offer at the university in the department of adult education. The idea was to look at “educating” adults – not merely providing literacy and numeracy skills. When I was appointed, my role was to set up income generation programmes for the poor. It was soon evident that people in urban slums most readily articulated livelihoods as their most pressing need: “we need jobs”. After starting a few income generation programmes – making dehydrated products, setting up tailoring cooperatives, we realized very soon this kind of training is actually not quite the right way to go about working with the poor.

Where was the problem?

Lakshmi NARAYANAN

(born in 1967) is social activist and researcher, a co-founder and former secretary general of KKPKP – Paper, glass, and metal workers’ association, a Pune-based trade union of self-employed waste pickers. She is also a co-founder of the Solid Waste and Collection Handling (SWaCH), India’s first wholly owned cooperative of 2000 waste pickers. SWaCH (also meaning “clean”) is India’s largest autonomous cooperative.Firstly, you never reach the poorest, because they are already working, otherwise they wouldn’t be able to survive. After a year’s work it was clear that the income generating programmes were not creating full-time jobs that would offer a minimum wage – the competition from the existing informal and unregulated market, which is engaged in several unfair trade practices, is too high. We wanted to reach the poorest. In the meantime, some children came and expressed their wish to learn to read and write. They were waste-picking kids. We included them in the literacy programme and started exploring what the conditions of their work were like: we went waste collecting with them ourselves. They were learning fast but their problem was that after tough excursions they were nodding off in class. To provide them some relief, we tried to get them access to segregated waste at the nearby housing societies to save their time spent going through the bins.

You started with kids, then.

We reached a few hundred citizens and institutions in the area and convinced them to segregate waste and that was when their mothers came forward, “Why don’t you give us segregated waste as well? We could then send our children to school”. It was exactly our position on child labour. If parents of working children in the same sector have access to better work, their kids don’t need to be working! We could then start a whole programme of enrolling them into schools. We started with 30 kids and 100 parents in one slum pocket and decided to institutionalize it a bit: brought out leaflets, told citizens to segregate their waste, etc. In the evenings we also took them to other slum pockets to mobilize others waste pickers. Staying in the waste pickers’ homes was the best way to mobilize them, and get them all together.

How did the waste pickers get to the slums in Pune? Where did they come from?

Most of them migrated from rural areas. In 1972 there was an enormous drought in the province of Maharashtra that forced people out of their homes. One big slum in Pune is actually called “Drought”, after the residents who all set it up after migrating after the drought. We have often had water shortages in India, there are drought-prone parts of our province. There are many landless labourers, toiling on other people’s lands. They are the ones who shifted. The very poor and the low-caste ones had absolutely no other choice than to go to the cities. It’s a big problem even today, it’s got to do with planning how water is used and distributed. The ones belonging to low castes couldn’t get work as domestic workers, therefore they ended up as waste-pickers. Most of them are dalits – the oppressed, former “untouchable” ones excluded from the caste system.

Is waste picking regarded as dirty work by Indian society?

It is dirty work. The work conditions are perhaps worse than in the other informal sectors, but the income is much higher. For instance, for vending you need space and some initial capital. Waste picking means the lowest entrance barriers: you need no education, no skills, no investment, only your physical energy and a sack. There are also very strong gender implications of this work. Waste is considered dirty and defiling. The people associated with waste are from lower castes, what is considered the lower gender – women – and what is considered the lower class – the poor. Therefore, the profile of a waste picker is a poor dalit woman except in the big cities like Delhi, Mumbai, Bangalore, Chennai or Calcutta.

What was the incentive behind creating a union?

At the same time as hundreds of households started to segregate waste after our campaign to ensure better working conditions for the women collectors, an entrepreneur appeared and wanted to seize the whole waste-picking business. After protests and solidarity waves he was forced out of the area, but we realized we cannot continue like this. Sooner or later someone else may try to do the same thing.

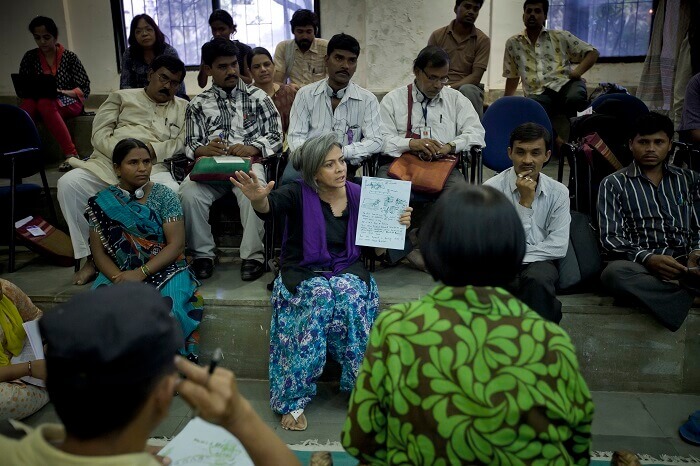

Staying in the waste pickers’ homes was the best way to mobilize them, and get them all together.

We proposed to form a union so that we would have a better position to communicate with the city and the state and take the issues forward. In Pune there was and still is this famous union of porters. We used this as an example.

What was the impact of creating a union?

We weren’t the first ones to work in the slums; there were hundreds before us and there have been thousands after us. The difference for the waste pickers as a sector was that they had never been organized before. There was hope for them that something was going to work out. 1500 waste pickers came to the first convention at their own expense. They spoke up and shared their issues. It was resolved that we register as a trade union because we felt it was important the workers themselves, society as a whole, and the municipality recognize it as work. It was imperative that this work gets the recognition it deserves. The board of the union was formed of two of our members (i.e. the university) and two from the dalit group. Then we started campaigning actively as we needed members. We went to every slum, encouraged all pickers to register and pay a membership fee. The idea was always that it is a union, a membership-based organization, so everyone is obliged to pay a fee.

How did you persuade them to join the union?

Some collectors were routinely harassed by the police. They were caught and accused of being thieves, of having stolen material in their sacks; some were even detained for a day or so. When we started the protest marches, the women were able to see the advantages of collective strength immediately. They were able to organize quickly, some 500 women would show up for a sit-in protest outside the police station. It proved to be very effective. The police started apologizing publicly – even returning money that they had extorted!

If I had to decide what to work on 20 years ago, I would have said, “Let’s work on waste issues – namely segregation of waste. And improve the access to waste for all pickers”. However, we’ve never chosen to decide what we thought was important. The collectors, obviously, are much better judges of that. They made it very clear what affected them the most: it was police harassment. Moreover, their work has been treated as invisible and criminalized. They had no rights. Our own issued ID cards started asserting that this is work, significant both for the environment and for city waste management. After several protests and negotiations, the municipality was persuaded to issue their identity cards as a sign of endorsement that the work they do helps the city. The card says the worker is entitled to collect waste from designated areas and she should be treated with respect.

I guess you didn’t stop with ID cards.

In the year 2000 we started a study with the International Labour Organization (ILO) that proved the work of waste pickers is saving the municipality several million rupees a year. On the basis of that we argued that the city should cover the workers’ insurance programme, which actually happened three years later.

What was the convincing moment for the municipality?

There was no convincing moment. Even now we are fighting for some issues. The struggle goes on. The point is that it has been a continuum; it moves forward in a progressive direction. In our work we have always used a combination of strategies: direct advocacy, talking to the elected representatives, we go to the politicians with the waste pickers. They are aware that these workers represent an important voting constituency for the municipality. The research findings were also important to the fact that a number of sensitive bureaucrats supported us.

How and why was the SWaCH cooperative established?

After establishing the insurance programme, the next logical demand was that the municipality should protect the right of the collectors to the waste and, therefore, the work. How could the city honour that demand? The best way was to institutionalize a system of waste collection from the doorstep for which a waste picker is considered a primary and priority candidate. We advocated for that and, finally, the municipality conceded. After long debates with the waste pickers, we found a cooperative the best model to take this whole movement forward. We had a very successful pilot year. SWaCH cooperative then gained a contract with the city to take care of waste management in the city of Pune. The cooperation with the city has been far from smooth, they paid their dues with delays etc. at times, but we kept the model going as waste pickers were being paid by the citizens.

How did you make sure the women were really empowered?

We were careful to ensure that both the union and the cooperative would reflect the reality that most members or workers in this sector are women. We know of too many trade unions, NGOs and cooperatives which take on work with a certain section of the society, but whose leadership doesn’t reflect the sector. Very often, the leaders turn out to be men while employing mostly women. True empowerment will only happen if waste pickers come forward and represent themselves. We also made sure only waste pickers became members, not their husbands or sons.

What does an ordinary day of a waste collector look like?

I will describe a waste picker of SWaCH: she starts her day at 7:30 in the morning. After leaving her house, she goes to the place where her pushcart is parked. She also has buckets, a uniform, gloves, a pair of shoes, and of course an identity card. There is a designated area for her: a certain number of households, she collects their waste, which is generally segregated into two categories: organic and recyclable. The picker takes the wet, organic waste to the compost place and sells the rest – paper, plastic and metal – to a scrap dealer. She gets her money per item, or per kilogram of material. At the end of each month every household that she services pays her a user fee, approximately 1 USD a month. A picker is usually able to service some 150 families, therefore she makes 150 USD by collecting fees and about the same amount by selling the waste to scrap shops.

Do waste pickers still live in slums, with a lot of children? That’s what the stereotypical profile of the urban poor would be.

Most of them do live in slums or poorer areas. The number of children is certainly decreasing. Young mothers would now have 2 or 3 kids. The second generation of collectors are literate, as many have invested heavily in their children’s education. Some are working in the union and the cooperative as accountants and other staff.

Is there a correlation between literacy, being educated and a better future in India? That’s what we keep hearing about getting people out of poverty in the countries of the Global South.

I do not have a very straightforward answer. I wouldn’t agree that someone starts earning more just when they get a degree because in India’s education system, unfortunately, we create a lot of highly educated people. We probably have the largest number of engineers in the world and we also have the largest number of illiterate people in the world. It is shameful. Our government has spent a lot on higher education and relatively less on primary education, which is why we have appalling levels of literacy. Equally, however, I believe just literacy is not going to solve all the problems. What we definitely want is the next generation to be literate and within the schooling system. Unfortunately, sometimes the educated descendants of waste pickers may end up earning less than the collectors themselves.

You have done a lot of non-violent resistance pointing out social injustice in society: child labour, police harassment, etc. You also deal with cases of rape. How do you assess the change and the transformative power of your actions? How empowered are the waste pickers nowadays?

[easy-tweet tweet=”True empowerment will only happen if waste pickers come forward and represent themselves. “]

Some of my very strong memories are, for example, about such a physically frail union member. She was not one of the louder waste pickers, not very articulate. We never realized the union had made any impact on her till her deaf-mute daughter was raped by one of the boys from the community. Not only did the woman fight on behalf of her daughter, but she also strongly resisted any attempts by the boy, the police and the local administration to affect the case – they all put on such a lot of pressure to withdraw the case. And she stood up against them, confident that she had many collectors behind who would fight the injustice with her. We just were amazed. They were willing to do anything to settle the case, even offering her money, but she got an interpreter for her daughter and the rapist was punished. There are so many cases when criminals get away with rape and to have a waste-picker fight it like this was very inspiring.

In one of the speeches you had in the Czech Republic, you mentioned the act of sending used diapers and napkins back to their manufacturers. What was the significance of that?

Despite the fact that many households have started segregating waste, the pickers still battle with items like sanitary waste. The municipality agrees with SWaCH that the manufacturers should be part of the solution in dealing with these soiled products. We have been trying to contact them for years and nothing was happening, but exactly one week after our Send-It-Back campaign – when they got the used diapers in their mail – they showed up in Pune. They feared the negative impact on the company, as the issue was in the press already. Unfortunately, they kept repeating they would raise awareness. Our point was: you could be raising awareness for the next 20 years, but the waste pickers need a solution today, as they are handling your products every single day.

Thanks to campaigning on these issues, finally the central government has mandated the companies to take responsibility about their problem product. It is not yet implemented. In Pune we will be trying for a creative model, which we hope to become a blueprint for the country.

How financially viable is your model?

The SWaCH cooperative is helping with what is clearly the municipality’s responsibility, as it has to handle waste effectively. We do not think the city’s poorest should be subsidising the municipality in any manner. The model works and is sustainable only if the city acts as a partner and is willing to contribute: not necessarily by paying the collectors but providing equipment, cover insurance and welfare benefits and enforcing policies.

The fun is in everything: every struggle, every sit-in, every discussion and meeting with the waste pickers.

We believe the municipalities and the government have to make sure the regulations are met. We are also aware of the fact that waste management is a very complex issue, and in the Western countries where the governments have focussed on centralized, high capital, technological solutions there has been a proliferation of technologies that are not environmentally sustainable in the long-run. Maybe economically they’ve sustained because the countries have more money, but we are not sure the centralized system of waste management is the best model for you either, and certainly not for us in India where we have such a huge labour force.

You have been in the waste picking environment for more than a quarter of a century, you’ve mentioned you have actually had quite a bit of fun. What did you mean?

The fun is in everything: every struggle, every sit-in, every discussion and meeting with the waste pickers. They have a great sense of humour, they are not sitting, crying, and moping about their situation. They are cheerful, pragmatic, courageous, and inspiring; they face their problems with a grin, ready to try new things. Waste-picking forces people to fight with dogs, cats, rodents, the police, etc. It makes them stronger. Moreover, they have always been inquisitive, challenging and asking the right questions, and made us reflect on what we can do differently. Generally, there is a lot of hope and optimism.

In the Czech Republic you have seen some social and solidarity-based economic initiatives: Veronica Hostětín Centre, Tři ocásci cooperative restaurant in Brno or Fair & Bio Fair trade coffee roasting house in Kostelec nad Labem. What was your impression?

In our country, many of us have opted to work through cooperatives because there is not much choice. What I find fascinating in many parts of the Czech Republic is that your people perhaps do not need to do it like in India, but there is a much stronger feeling that they should be doing it, which is why they are coming together. It is impressive to see the willingness to work together so that the situation doesn’t get out of hand.

***

This interview was made in April 2016, when Lakshmi Narayanan visited the Czech Republic and Greece on a tour focusing on initiatives of social and solidarity-based economy, co-organized by Ekumenická akademie, the Czech partner in the European SUSY project – Sustainable and Solidarity economy.

This interview first appeared in A2 11/2016.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)