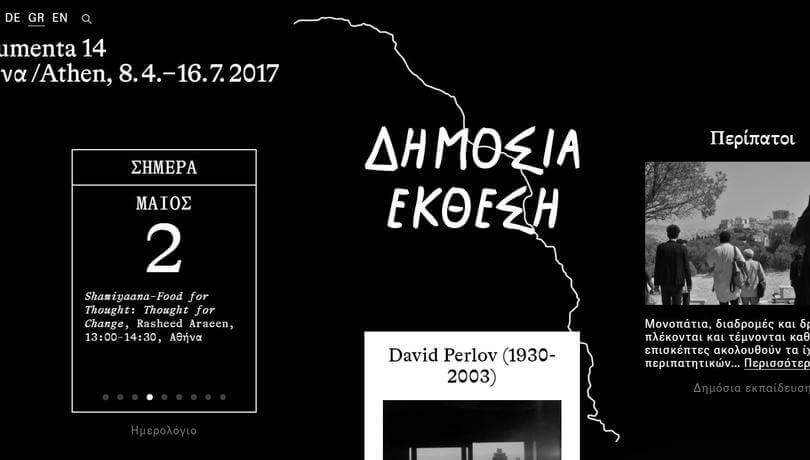

Documenta is considered one of the most important exhibitions in the world of modern arts. It has taken place every 5 years in Kassel, Germany, since 1955. It has been associated, ever since its beginning, with anti-fascism and anti-racism, due to the artists who initiated it wanting to oppose the cultural darkness of Nazism and create a free path for documentation on the modern art. For the first time since the establishment of Documenta, the current artistic director, Adam Szymczyk, decided to move the exhibition for 3 months to Athens, Greece, in order to learn from the financial and social situation that the city has been experiencing in recent years due to the economic and refugee crises.

Documenta und Museum Fridericianumg GmbH administered the application procedure, as well as the employees’ selection, and it takes full responsibility of the contracts.

The relocation of the exhibition produced a feeling of excitement across the art and art-loving world, as well as for Greek young people who could have an opportunity to work at a prominent art event such as Documenta. Many jobs opened, which were filled by a lot of Greek workers. Around 200 people were hired into invigilator positions, who were informed during their interviews that the gross wage would be 9 euros per hour. Two weeks after the opening of the exhibition, a period during which invigilators were already at their postings, they were called to sign their work contracts which contained changed information and terms with which employees did not want to agree and sign: the gross wage had been reduced to the sum of 5.62 euros per hour. In a personnel meeting between the administration of Documenta and invigilators, the matter was discussed after employees decided not to sign the contract, in which the administration said that there was some kind of “misunderstanding” during the interviews. Further, they claimed that during the interviews, what they meant as regarded 9 euros per hour was that this amount included expenses of the company for administrative costs of having employees. More to the point, they didn’t mean that the entire amount of 9 euros would be wage they would receive. Obviously, that was not at all clear to the employees during the interviews. Documenta explained that the contracts weren’t directly linked to their own administration, but instead to the mediating corporation MAN POWER –a fact of which employees were not aware or informed. In a collective letter written by employees that was published soon after the problem appeared, the authors commented that “it is obvious that our wages were reduced in order for the cost of the mediator to be covered.” Additionally, there was a discrepancy between the working hours and days that were agreed on.

This collective open letter, which thoroughly described the situation, was published on several Greek online media. Documenta’s administration offered their response online some days later, commenting that, “given the large amount of the employees (200 individuals) that was needed concurrently to be hired and to start working for a short period of time, Documenta und Museum Fridericianumg GmbH is cooperating with a human resources service provider for procedural reasons, which took over the completion of the contracts and the hiring of the invigilators.” They also stated that, “Documenta und Museum Fridericianumg GmbH administered the application procedure, as well as the employees’ selection, and it takes full responsibility of the contracts. The payment of the human resources service provider has nothing to do with the wages of the invigilators.”

After some weeks of open discussions and negotiations with the administration of Documenta, the organization provided to invigilators a new contract, but with terms that were almost the same as the ones that had been agreed upon at the job interviews. The employees were satisfied with the administration and the final contract. In the same announcement that was mentioned before, Documenta stated that, “the monthly salary of the majority of the invigilators in Athens, who work 30 hours per week, is between 800 and 940 euros. Every legal working bonus is provided, in accordance with the Greek regulations.”

There is the aspect of corporate function, which works with vertical structures, strict internal hierarchies, and the equivalent labor culture.

Thus, everything turned out well: on the one hand, Documenta showed its social face, processed the claims of the employees, and didn’t violate worker’s rights. On the other hand, invigilators were satisfied with what they gained in the end. In an open letter by the Invigilators Open Discussion of Documenta, which seems to give closure to the matter, the authors described what happened, commented on the way the administration of Documenta handled the problems, and highlighted the need and the importance of collective claims that can achieve success even in times of social injustice, crisis, and financial difficulty. They expressed the rather negative impression that they got from the public announcement/response from Documenta, which “forgets to mention that our wages are a product of assertion from the side of employees.” They also state that, “ through our collective mobilization, we managed to apply pressure and make Documenta respond right away…There is no doubt that the experience of a collective claim has been valuable and ‘educational,’ staying true to the language that this year’s Documenta is using. Nevertheless, through this experience we learned that there are two sides to every story. On the one hand, there is the radical narrative of Documenta14 and the public actions that bring to light several aspects of social consequences that are due to the austerity of countries in the South, as well as the radical anti-fascist political inheritance of Documenta14, which has its start line in post-war Germany. On the other hand, there is the aspect of corporate function, which works with vertical structures, strict internal hierarchies, and the equivalent labor culture.”

Last but not least, the employees at Documenta aimed to underline that “the importance lies in the fact that we learned that even in conditions of social crisis and high unemployment, the collective claims of workers bring results and gain victories, big or small.”

In a discussion with invigilators, we discovered that, despite the problems that arose during the last month, the working environment is decent and progressive, and the whole experience is interesting, having educational value for several reasons. They also told us that the artistic manager, Adam Szymczyk, showed quick reflexes on the matter, took part in some open discussions, and tried to be helpful with finding solutions. Let us hope that Documenta will continue having the social impact that the art world needs, and more importantly, let social fights continue to gain victories.

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO.png)

![Political Critique [DISCONTINUED]](http://politicalcritique.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Political-Critique-LOGO-2.png)